Is the 25 year bull run for house prices over?

House prices always incite a lot of interest in Australia. Until recently it was all about surging prices and ever-worsening affordability as prices boomed. But the focus is shifting to the emerging slowdown in the face of rising interest rates. This wire will examine the main issues, as well as look at some of the options around how to fix the crisis.

The state of the home

Last year saw national average home prices rise 22%, their fastest 12-month increase since 1989, with gains propelled by record-low mortgage rates, home buyer incentives, coronavirus driving a switch in spending to “goods” like housing, recovery from the lockdowns, a lack of supply and a fear of missing out.

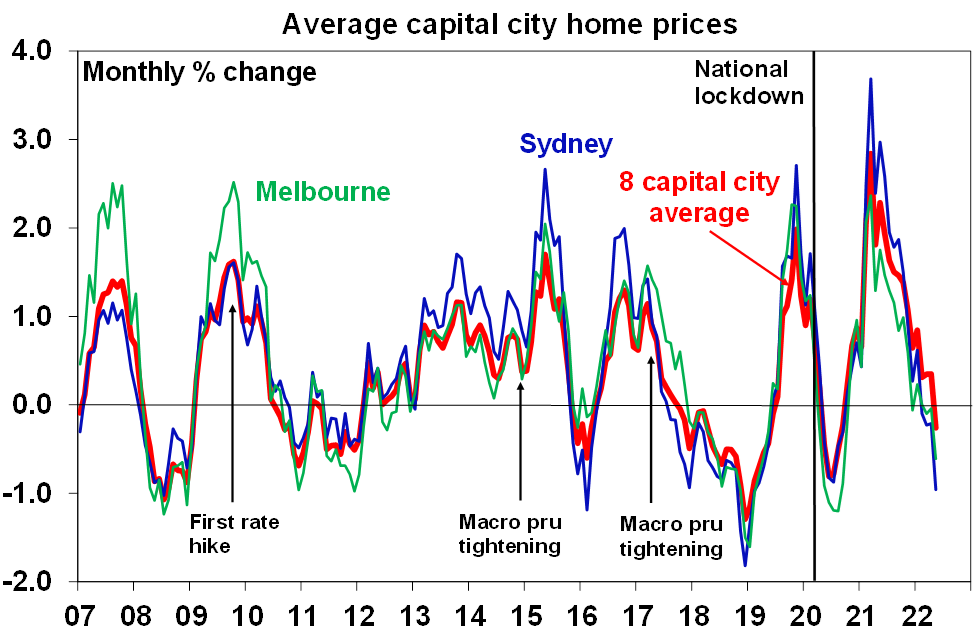

However, the monthly capital city and national price growth peaked in March last year at 2.8% and has trended down to just 0.3% for capital cities in March this year.

The slowing trend since March last year has been led by Sydney and Melbourne, with prices now falling in both cities.

In contrast, price gains remain very strong in Brisbane and Adelaide with property demand in Brisbane benefitting from strong interstate migration, and these cities seeing less of an affordability constraint and very low listings. Perth is accelerating, helped by its reopening to other states. Finally, regional price growth remains very strong.

The outlook for house prices

National average property prices are likely to peak around mid-year and then enter a cyclical downswing. After 22% growth in national average home prices last year, average home price growth this year is expected to be around 1% and we expect a 5-10% decline in average prices in 2023.

From top to bottom, the fall in prices into 2024 is likely to be around 10 to 15%, which would take average prices back to the levels of March/April 2021.

This is likely to mask a continuing wide divergence. Sydney & Melbourne look like they have already peaked & are likely to see falls at the high end of the range. But Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth & Darwin, and regional areas are less constrained by poor affordability and are likely to see shallower falls.

What goes up, must come down

A common property myth is that home prices only ever go up and never fall. But a simple look at history tells us this is not so.

- Real house prices in Sydney fell 36% in 1934-35, 32% in 1937-41, 41% in 1942-43, 12% in 1947-48, 14% in 1951-53, 12% in 1961-62 and 22% in 1974-77.

- In nominal terms, CoreLogic data shows that Sydney dwelling prices experienced top to bottom falls through every decade since the 1980s.

- Similarly, capital city average prices have also had top to bottom falls (of greater than 5%) in every decade since the 1980s.

Key drivers of the current downswing

The slowdown in property price growth already underway and the likely fall in prices ahead reflects a combination of:- Poor affordability: Over the last 25 years, average capital city dwelling prices rose 358% compared to a 113% rise in wages. So prices rose more than three times that of wages. From their most recent low in September 2020, prices have gone up 20% versus just a 3.7% rise in wages. This has priced more home buyers out of the market.

- Rising fixed mortgage rates: These have more than doubled from their lows & are still rising, reflecting rising bond yields.

- RBA rate hikes: The RBA hiked rates earlier this month, pushing variable mortgage rates up. Rough estimates suggest that a 1.5% to 2% rise in mortgage rates would reduce homebuyer borrowing power and the ability to pay for a house by 10 to 15%.

- High inflation is making it even harder to save for a deposit.

- Higher supply in Sydney and Melbourne as a result of vendors seeking to take advantage of high prices and solid construction after two years of zero immigration.

- A rotation in consumer spending back to services as reopening continues may reduce housing demand.

- Finally - and crucially - a decline in homebuyer confidence.

The major driver is the rise in interest rates. While the property slowdown appears to be starting earlier relative to the timing of RBA rate hikes this cycle, this reflects the bigger role ultra-low fixed-rate mortgage lending played this time around in driving the boom.

Previously, fixed-rate lending was around 15% of new home lending. However, over the last 18 months, that figure has jacked up to around 40% as borrowers took advantage of sub 2% fixed mortgage rates.

Now, fixed rates are up sharply which is taking the edge of new buyer demand well ahead of RBA hikes.

Will we see a house price crash?

House price crash calls have been a dime a dozen over the last two decades, only to see the boom roll on after periodic dips. So, the experience since the early 2000s warns against getting too bearish.

Some would see a 15% fall in prices as a crash, but I take it to mean prices falling 25% or so.

Our assessment is that while a crash is possible, it is unlikely unless we see very aggressive rate hikes – say taking the cash rate to 4 or 5% - or much higher unemployment, driving a sharp rise in defaults and forced property sales.

Several factors argue against a crash:

- RBA analysis suggests the “majority of households are well placed to manage higher…loan payments” and that for example, just over 40% of variable rate borrowers would see no increase in monthly payments from a 2% mortgage rate rise as they are already paying in excess of the minimum.

- The RBA will only raise rates as far as necessary to cool inflation. It knows that high household debt levels compared to the past mean that the household sector is more sensitive to higher rates and therefore it won’t need to raise rates as much as in the past to cool spending and, hence, inflation.

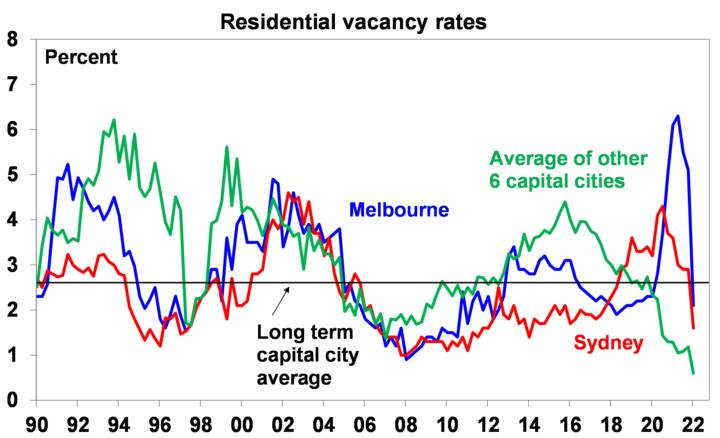

- Very low rental property vacancy rates suggest that the underlying property market remains tight.

- The increase in home deposit schemes and rising immigration will help place a floor on housing demand.

However, the risk of a crash cannot be ignored given the high level of household debt and that it’s been more than 11 years since the last rate hike in Australia, meaning many current borrowers have never seen a tightening cycle.

Are we near the end of the 25-year home price boom?

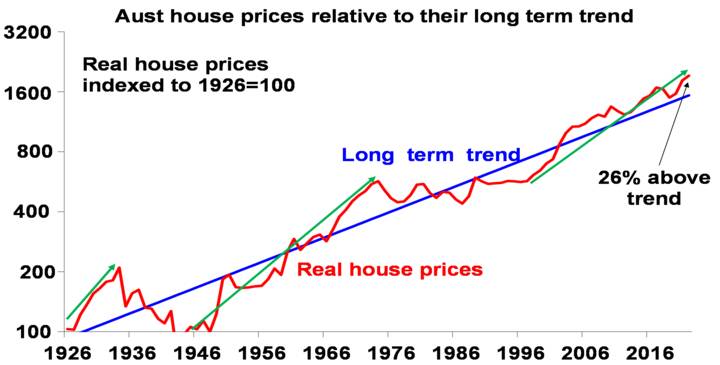

The past 100 years have seen 3 major long-term booms in Australian home prices – in the late 1920s, the post WW2 period, and since the late 1990s.

These are highlighted with green arrows in the next chart that shows real house prices back to 1926. The boom over the last 25 years has largely been driven by the shift from high interest rates toward low interest rates and a surge in population relative to housing supply.

What will be the impact on the economy?

The housing downturn will affect the economy via negative wealth effects on consumer spending (ie, wealth goes down, we feel poorer, we spend less) and a slowing in housing construction. The former was a significant drag on the economy in the 2017-19 period when a 10% fall in average home prices contributed to a significant slowing in consumer spending.In a way, the negative wealth effect of falling home prices means that the slowing housing cycle will do some of the RBA’s work for it, which means there is a good chance that it will pause tightening next year (at around 1.5% for the cash rate) – which in turn should limit the fall in house prices to 10 to 15%.

What to do to permanently improve affordability?

My shopping list on this front includes:- Measures to boost new supply - relaxing land-use rules, releasing land faster, and speeding up approval processes.

- Matching the level of immigration in a post-pandemic world to the ability of the property market to supply housing.

- Encouraging greater decentralisation – the work from home phenomenon shows this is possible but it should be helped along with appropriate infrastructure and housing supply.

- Tax reform to replace stamp duty with land tax (making it easier for empty nesters to downsize) & cutting the capital gains tax discount (to remove a pro-speculation distortion).

Neither side of politics is offering a serious effort on this front.

4 topics