Is value investing dead?

Ellerston Capital

One of the accepted tenets of investing had been that value investing rewarded its adherents with superior performance through time - in return for accepting the pain of social isolation that comes with buying unloved and discarded businesses whilst others laugh at you.

The four most dangerous words in investing are, “it’s different this time”.

Sir John Templeton

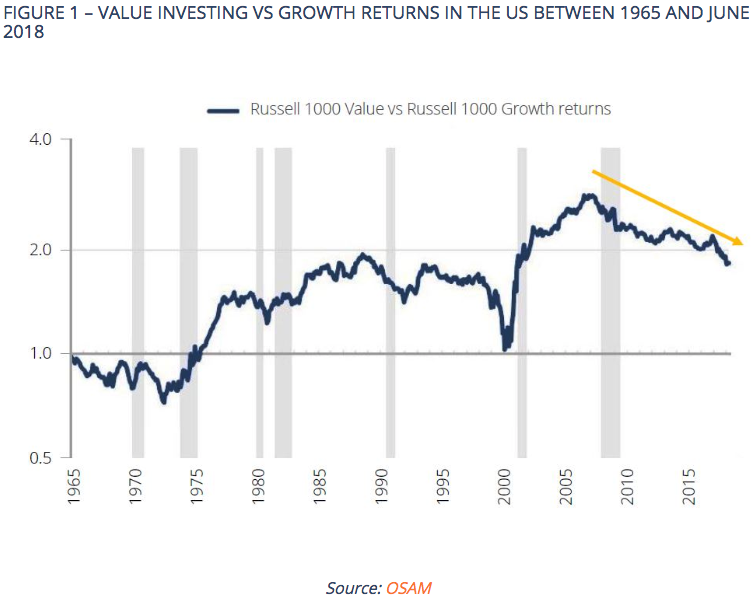

And this was indeed true for many years. Figure 1 below shows the returns of value investing in the US compared to following a growth style (where investors pay more for stocks growing swiftly) back to 1965. But since 2007, this recent period of value investing lagging growth has been so severe that value investing has given back all its gains since 2002 and now we are back to where it was in 1988.

There’s patience and there’s patience – more than 30 years of no excess returns to value is the longest on record and should make one at least consider whether the model is broken.

O’Shaughnessy Asset Management out of the USA, a value adherent like us, with a similarly open model of publishing their thoughts did an excellent walkthrough of the dimensions of value and growth investing – which I will draw on heavily here.

Firstly, it dispelled some myths about the current value underperformance period. One myth espoused by value adherents is that we are just in another Tech bubble and the underperformance is due to these FAANG stocks outperforming.

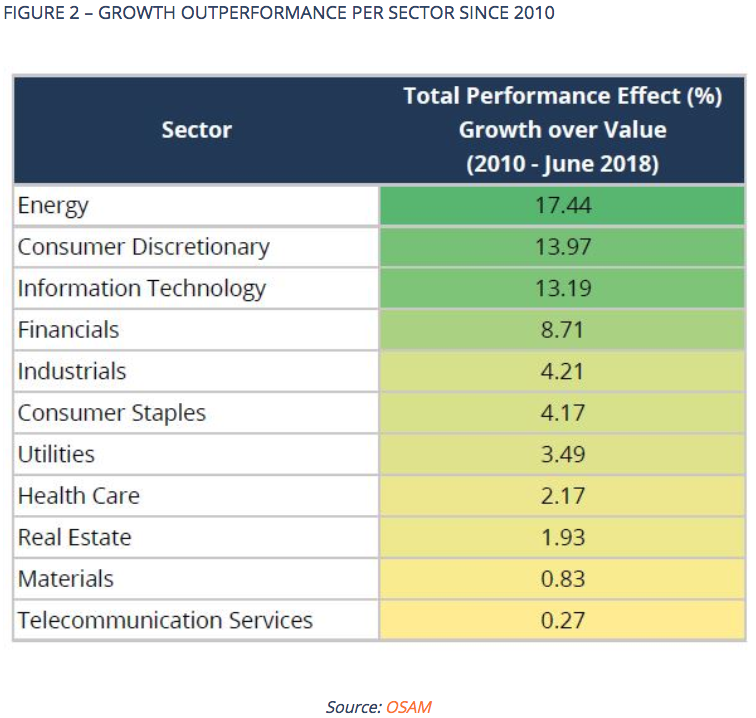

However, when OSAM went through each listed sector (Figure 2), they found, somewhat remarkably, that growth investing had outperformed value in every sector in the USA since 2010!

This is not just a “tech bubble” story. Something else is going on amongst the listed companies of the world (which we will return to later).

So how did you make money out of value investing strategies (i.e. why did markets reward you for this style of investing previously)?

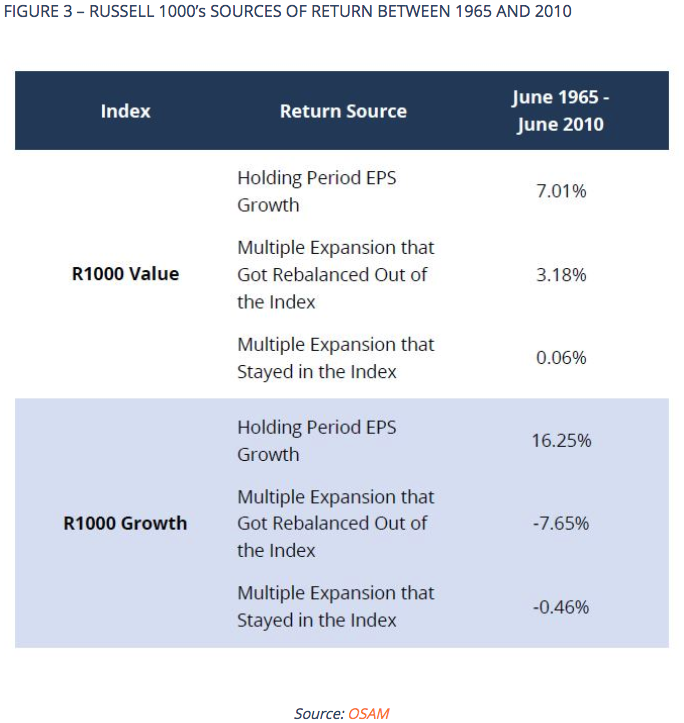

OSAM used the Russell 1000 as their starting point – an index similar to the All Ordinaries – except it comes as a “value” and a “growth” form. Figure 3 below shows a decomposition of returns from 1965 to 2010.

Firstly, one can notice that growth companies do in fact grow faster than value stocks. That is, they are better businesses.

But investors are not the founders and thus they must acquire it (the shares) on the stock market. The price they buy and sell at reflects what others think the business is worth: investors trade in the perception of businesses.

Value investors make money not because value stocks are fast growing or great, but because value stocks aren’t as bad as people thought they were, so they re-rate (higher P/E) as opposed to growth stocks which aren’t as good as people hoped they were and they de-rate.

So 7% EPS +3% re-rating = 10% is > than 16% – 7% = 9% return for growth stocks. Whilst this may not seem like a lot, this average 1% per year adds up to large numbers over long periods of time.

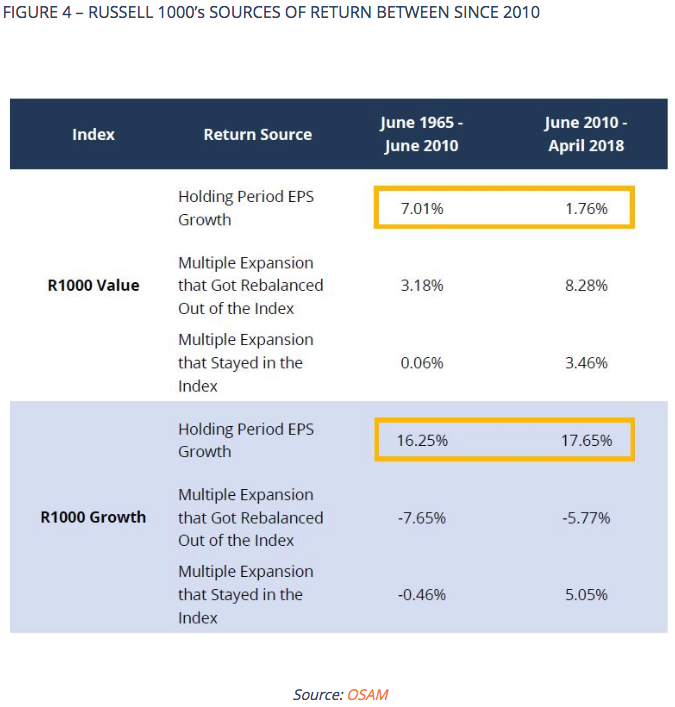

Now compare this to the table for the period since 2010 (Figure 4). What is noticeable is that growth in earnings (business growth) is largely in line for the first table for the growth stocks, and whilst the de-rating has moderated, what jumps out is the collapse in earnings growth in value stocks – from 7.0% to 1.8%. The only reason value stocks haven’t fallen behind more is the market has re-rated them, hoping that this lacklustre earnings growth will pass.

Like it or not, something really is different for the value stocks in their real-world operations – they are not delivering the EPS growth they used to.

So, what's happening?

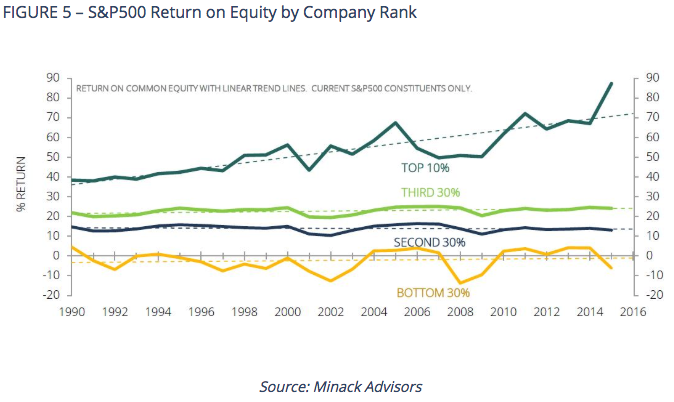

Minack Advisors’ principal, Gerard Minack who also sits on the Board of Directors at Morphic, has a chart that graphically represents what is taking place. Figure 5 represents Returns on Equity (RoE) split for the USA by groups from best to worst. Over long sweeps of history, the spreads were relatively constant. This is because, over time, new competitors would emerge and compete away incumbents’ higher returns, poor business would consolidate and raise prices and so on. Schumpeter’s “creative destruction”.

We can see that “good businesses” are pulling away from the pack, leaving scraps for the rest and death for the bottom (where value investors often look). If we link back to the FAANG technology stocks, newer industry entrants have tended to become monopolists very quickly – think how many internet browsers you use; car apps; travel websites etc. These have all been called “platform companies” and they don’t seem to suffer from the dis-economies of scale older businesses had.

So how could things return to normal? 100 years of data says value has always found a way to come back. If I am to speculate, it could be regulation. The monopolist of the “oil age” of the 1900’s – Standard Oil – was broken up by new regulations and never really recovered. The same fate may await Amazon and Facebook, destroying their platform model. President Trump certainly has Amazon in his sights.

Though relying on regulation for value investing to work again could be a long wait. This is a real challenge for value investors like ourselves. If the companies we are buying are cheap, but they are no longer growing their earnings, then total stock returns will struggle to keep up.

What can value investors do?

Whilst we started with Sir John Templeton’s wise words counselling against thinking things are different, sometimes the world does change and one needs to be open to that possibility as well.

“Adapting” to this world for a value investor can mean a few differing things.

Firstly, “long winters” (like the current one for value investors) have occurred before and are often the hallmark for strong future returns as pessimism has taken root in the valuation, baking low returns in. This low valuation is present today.

Secondly, “adapting” is key. Value is just one factor in an investment process. Important, yes, as it tells you that you are not over-paying, but there are other signals that can be used. One is “momentum” or trend. Large investment house AQR has produced a plethora of data analysis showing how adding trend signals to a value-based investment process can enhance returns dramatically.

Thirdly, stay out “junk”. Now, one investor’s trash is another’s treasure, but research has shown that avoiding the cheapest stocks with bad characteristics in value stocks, say the bottom of the Figure 5above, effectively enhances returns for value investors. In Figure 6, looking at the rankings from “Quality” to “Junk” of businesses, one can see that avoiding the value destroyed by the weakest businesses is more important than choosing the highest quality.

Or as OSAM puts it: “avoiding junk is more useful than buying quality.”

Now this is interesting for a long-only manager, but for Morphic who can short-sell “junk” stocks to profit from their fall, this insight adds another way to profit, particularly when value is struggling as a style. Shorting “junk value” is a promising area of focus.

Some sectors and industries, like banks, have unique data which may help us better identify junk and Morphic has specially focussed on these data sets in choosing some of the US regional bank stocks we have owned over the years.

In short, there are a number of insights from academia and industry participants that show how a value-based investor can navigate to survive this more challenging period.

Or to finish with words from the other end of the investing spectrum, Paul Tudor Jones, the renown hedge fund trader:

“You adapt, evolve, compete, or die.”

Want to learn more?

For more information and additional insights from Morphic Asset Management, please click here.

Chad co-founded Morphic Asset Management in 2012. As a stock picker Chad is also a generalist but has strong regional knowledge of Europe and the Americas. He has also been awarded the CFA Charter.

Expertise

Chad co-founded Morphic Asset Management in 2012. As a stock picker Chad is also a generalist but has strong regional knowledge of Europe and the Americas. He has also been awarded the CFA Charter.