Keepwell deeds may yet leave offshore Chinese bondholders feeling unwell

The recent question marks over the outlook for China’s Evergrande property group has raised concerns over the structure of some offshore bonds issued by Chinese companies; notably the ability of keepwell deeds to provide a satisfactory level of protection for bondholders. In light of this, it’s worth taking a closer look at keepwell deeds and the implications of a recent courtcase for their ongoing viability as a source of credit enhancement.

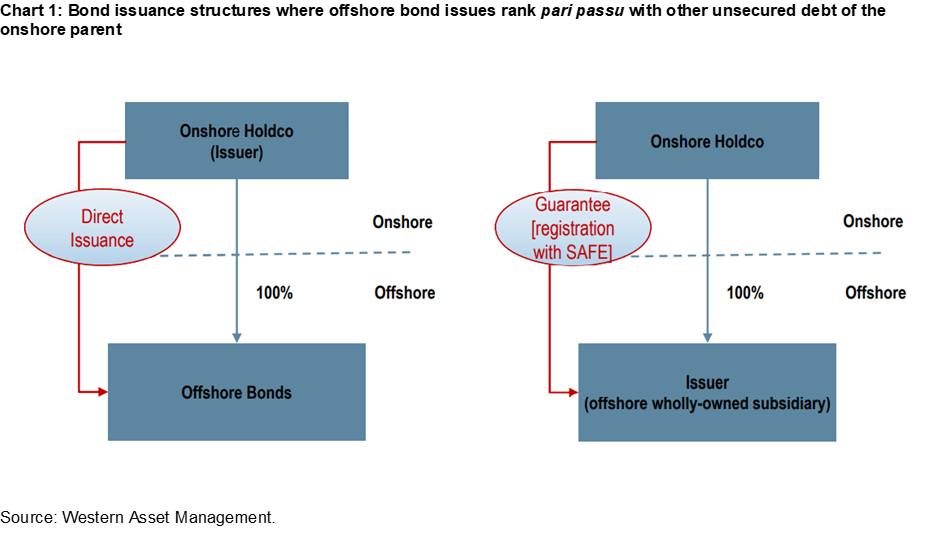

When considering offshore bond issuance, it’s useful to separate the types of structures according to whether bond investors rank ‘pari passu’ (on equal footing) with all other unsecured debtholders of the issuer/onshore parent. Most investors would be familiar with the direct issuance approach whereby an onshore Chinese company issues bonds offshore directly via the onshore entity or offshore wholly-owned subsidiary.

The credit rating of such issues is directly linked to the ability of the parent company to service its debt obligations with offshore bond holdings ranking pari passu with other unsecured creditors of the onshore parent. Accordingly, such issues are popular with Chinese companies possessing strong business models/balance sheets and solid reputations. Such bonds will generally include a direct guarantee if the issuance is through an offshore subsidiary, though this will need to be registered with the Chinese State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). These types of offshore issues make up the majority of offshore bonds issued by Chinese companies and tend to be issued by major state-owned enterprises or quasi government authorities.

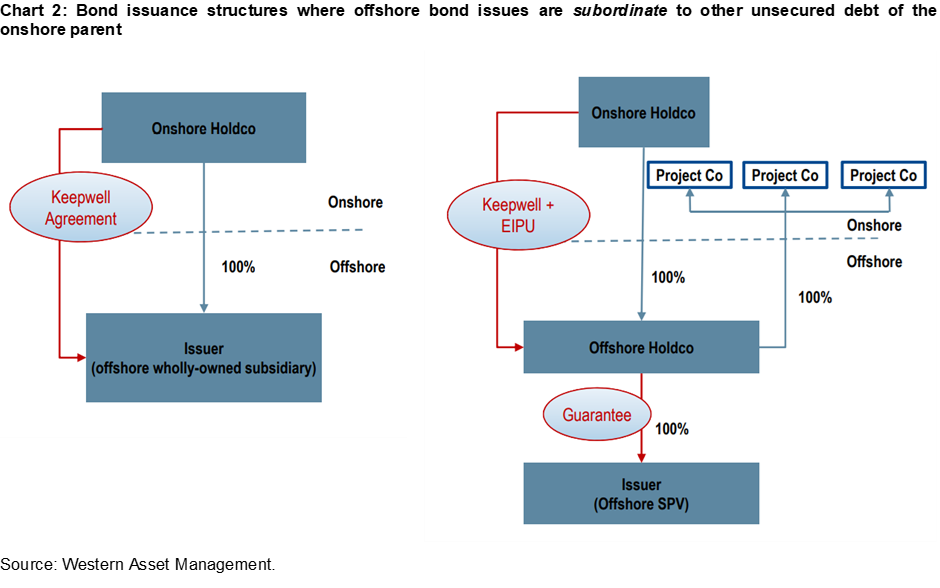

For non-top tier Chinese issuers, offshore bond issuance through a subsidiary is more problematic without some form of credit enhancement. As the subsidiaries are in a weaker financial position, given it often has limited assets, a guarantee from the onshore parent, which is responsible for the main business and holds the core assets, may often be required to attract borrowers to hold the bond. Yet a direct official guarantee from the onshore parent company can be problematic, as it will be required to comply with China’s foreign exchange regulations regarding cross border guarantees, i.e. requires official regulatory approval. To avoid the requirements of formal regulatory approvals, offshore bond issues have evolved to include within their covenants what are referred to as keepwell deeds. A keepwell deed is a contract between the parent company and its offshore subsidiary in which the parent provides a ‘promise’ to keep the subsidiary solvent and in good financial health by maintaining certain financial ratios or equity levels. These deeds differ from a bond guarantee as they only allow creditors to force the credit enhancement provider to supplement the liquidity of the issuer for bond payment, instead of paying the debt directly. This distinction is further reinforced in that, whilst a keepwell arrangement creates an obligation on the provider to ensure the issuer or borrower has sufficient funds to pay its liabilities, it’s usually expressly provided in the keepwell deeds that they do not constitute a guarantee. That keepwell deeds do not comprise formal guarantees normally results in the offshore bonds issued under such arrangements rating below that of the onshore parent.

For completeness, though somewhat as an aside, it’s worth noting that Equity Interest Purchase Undertakings (EIPU) may also be utilised to supplement keepwell deeds. An EIPU is where the parent company agrees, subject to the consent/approval of Chinese regulators, to purchase the assets of the offshore issuer and its onshore subsidiary to cover any debt obligations of the offshore issuer in the face of a default risk. The structure with an EIPU becomes more complex as it requires the offshore holding company to have interests in onshore assets/projects and may involve issuing the bonds via a Special Purpose Vehicle.

To ensure the protection of bondholders’ interests, a typical keepwell deed involves a Chinese onshore parent company undertaking to :

- maintain effective control over its offshore subsidiary;

- provide adequate funding to the subsidiary to fulfil its payment obligations; and

- not impose adverse covenants on the assets of the offshore subsidiary.

For issuers, the benefits of using a keepwell deed over a formal guarantee are they :

- don’t require regulatory approval;

- provide the issuer with greater flexibility in the repatriation of funds; and

- don’t constitute a contingent liability for the parent company.

The benefits arising from utilising keepwell deeds as a means of credit enhancement makes them particularly attractive for lower-quality or more highly-levered issuers such a property companies.

Potential issues with keepwell deeds

That keepwell deeds are not recognised guarantees within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) legal system creates complications when deciding exactly where offshore bondholders stand versus other onshore, unsecured creditors to the parent company. The legal complications with keepwell deeds arise not only from the nature of the deed but the potential overlap in legal jurisdictions. Unlike regular bonds, where an investor makes a debt claim against the Chinese parent company for non- payment of principle or coupon of the bond (a default event), to enforce keepwell deeds, the investor needs to claim for breach of contract against the parent company. On the face of it, this should not be an issue since being offshore bonds keepwell deeds are usually governed by laws other than PRC law and therefore are interpreted and enforced under the laws of the country of legal domicile or issuance (typically Hong Kong). However, when a restructuring application against a company has been accepted by a court in Mainland China, China’s bankruptcy law provides that the Chinese court has exclusive jurisdiction to hear any dispute against the company. This may be interpreted to include a dispute regarding whether a keepwell deed is enforceable; especially where this is linked to bankruptcy or restructuring proceedings. The question then arises, should the enforceability of keepwell deeds be decided by the Chinese courts as part of the restructuring proceeding, or by Hong Kong courts in accordance with contract law dealing with the terms of the keepwell deed? The existence of a legal overlap raises question marks regarding the ultimate interpretation and enforceability of keepwell deeds. Nowhere is the potential impact of this overlap more apparent than in the recent legal case involving CEFC Shanghai International Group Limited (CEFC).

As background, in July 2018 (prior to the bankruptcy of CEFC), a claim was filed in the Courts of Hong Kong against CEFC for breach of the keepwell deed in connection with its offshore bonds. Default judgment was issued by the Hong Kong court, ordering CEFC to pay principal, interest and costs to the bondholder. The defendant, however, resisted the enforcement of the judgement made by the Hong Kong court that recognised and enforced the keepwell deed. In May 2019, the bondholder applied to the Shanghai Financial Court to enforce the Hong Kong judgment. The defendant in turn argued that the keepwell deed should be properly categorised as a guarantee, which would be subject to approval by the SAFE. As the keepwell deed never received approval from the SAFE, the defendant argued that the enforcement of the keepwell deed was contrary to Chinese public policy. In November 2020, the Shanghai Financial Court ruled that the default judgment was a final decision and ordered the Hong Kong judgment be recognised and enforced in the PRC.

At face value, it would appear the ruling reaffirmed the legal standing in the PRC of the keepwell deed in offshore financing structures. Yet muddying the waters is the way in which the PRC court appears to have reached its judgement. In reaching its judgement, the Shanghai Financial Court considered whether enforcement of the Hong Kong judgment would be contrary to public interests of the Mainland. Significantly, as the deed was not governed by PRC law, the Shanghai Financial Court did not base its judgement on how PRC law interprets the nature and effect of the keepwell deed. Reflecting this, the Shanghai Financial Court stated in its judgement that refusal should generally only be given when enforcement would be “directly” contrary to public interests. It concluded that enforcement in the present case would not affect the interests of an “unspecified majority” in the Mainland and therefore would not be contrary to public interests.

Despite the positive judgement, the application of what appears to be a ‘public interest’ rationale may yet prove to be a double-edged sword. On the positive side, the Shanghai Financial Court ruling highlights that any attempt to resist the enforcement of keepwell deeds by the borrower based on Chinese public policy is unlikely to be endorsed by PRC courts. The judgement therefore reaffirms that a keepwell deed is an instrument which is short of a guarantee yet is recognised in the PRC as constituting an obligation which can be enforced against its provider. Yet the very nature of the ‘public interest’ rationale underpinning the ruling, in the absence of adequate case law precedent in the PRC, means that it remains to be seen whether based on different facts and background the same judgements would be reached. This raises the prospect that the enforceability of keepwell deeds within PRC courts may be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Though bonds with keepwell deeds comprise less than 20% of offshore bond issuance by Chinese companies, they are often used by private sector companies, particularly property developers. Their legal enforceability to protect offshore bondholders has therefore become increasingly relevant given the move by the central government of the PRC to clamp down on excessive borrowing by companies within key sectors. For investors in such bonds, the potential for the effectiveness of this type of credit enhancement to be determined on a case-by-case basis by PRC courts raises the risk premium around such issues. Whilst in time we may get a clearer picture of how keepwell deeds will be interpreted by the PRC courts, for now there remains much uncertainty. For investors, this uncertainty highlights that it’s not just the underlying credit worthiness of the parent company which is important, but also the legal enforceability of the attached covenants which will determine the ultimate quality of a Chinese offshore bond issue.

1 topic