Long-term returns: Is Trump a threat to equity dominance?

High yield bonds have also done very well, especially relative to the volatility of returns. Market dips have been bought and shocks have not had a long-lasting negative impact on returns. Going forward this may remain the case. However, uncertainty around US President-elect Donald Trump’s potential policies could upset the growth and inflation outlook, which in turn may cause market returns to sharply deviate. As always, investors need to balance the strategic with the tactical.

Not crystal clear

If you are not already inundated with 2025 market and economic outlooks you will be soon. Spoiler: no-one knows what is going to happen next year. The reason? Trump of course, and his policies, and the unknown global responses to them. The consensus seems to be that in the US we will see higher growth, inflation and government borrowing, which might be a problem for the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the bond market. For the rest of the world, it looks like mostly bad news. Tariffs will hurt - China will struggle to boost its economy amid ongoing weakness in the property sector, and Europe is tightening fiscal policy.

For the moment though, the markets are collectively shrugging. US Treasury yields have fallen since the election, so have inflation break-even spreads, while the S&P 500 keeps achieving new highs and credit spreads are steadfastly tight. European equities have underperformed since the election but that is nothing new. There will be more meaningful market moves next year but for now it is all quite calm. Happy holidays!

Strategy…

From an investment point of view the uncertainty around Trump is certainly an issue. This makes it hard to set out an investment roadmap for the coming couple of years. One approach would be to go with what has worked already – be exposed to US equities and the dollar and have some credit for income with US high yield being the most attractive credit asset class in our view – or for European investors who hedge the currency risk, European high yield. A second approach is tactical - dynamically adjusting portfolios to navigate the materialisation of any risks and the emergence of any clear value opportunities. Of course, this approach is at the mercy of market timing but there could be some opportunities created by volatility or the need to reduce risk. European fixed income markets currently provide some relative value trades that may turn out to be profitable – buying French government bonds versus swaps, holding other government bonds such as Italy and Spain and looking for spread dispersion opportunities in corporate credit. The fall of Michel Barnier’s government in France seems to have been priced in. Spreads on French government bonds narrowed a little following the no-confidence vote, reflecting the view that the budget will be somewhat fiscally restrictive.

For the slightly more medium term, taking a view on duration in the US, or on inflation protection, means betting on a particular macroeconomic outcome to manifest over the next year. That is not easy. Most bond investors are likely to play the range in US Treasuries and the volatility will, for now, mostly be driven by expectations on how much the Fed can cut rates before the bulk of Trump’s agenda hits the economy.

Or strategic

The third approach is to set out a strategic asset allocation based on long-term performance metrics of different asset classes, and then act tactically, when and if things start to go wrong, or new opportunities present themselves. Precisely how this is achieved depends on an investor’s time horizon and risk tolerance. If we assume past performance is some guide to future returns (a cardinal sin), setting a strategic allocation based on history is not a bad approach as investors can choose, broadly, where they sit on the risk curve depending on the implied return and volatility which is somewhat inherent in the behaviour of publicly-traded financial assets.

Long-term pointers

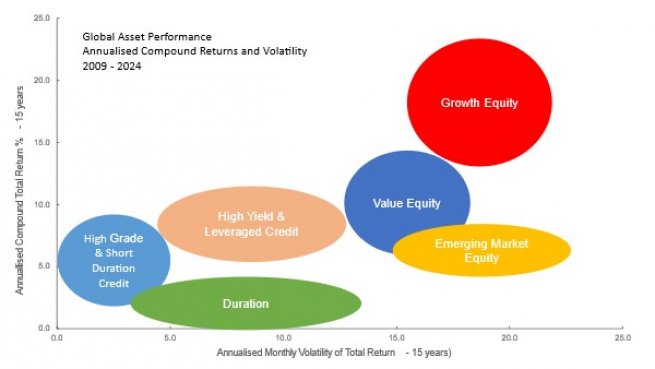

This week I looked at total returns for several assets across fixed income and equity markets over the last 15 years. Plotting the returns against the realised annualised volatility of monthly total returns generates some bunching of asset class performance. I put them into six categories (seven if I include cash) – growth equities, value equities, emerging market equities, high yield and leveraged credit, high grade credit, and duration.

The chart below is a stylised version of the more detailed chart. There are some interesting messages. Investors have done well by being exposed to growth equities and high yield over the last decade and a half. They have both delivered the best risk-adjusted returns and, outside of recessionary periods, should continue to do so. Growth equities represent technological innovation and the manufacturing supply chain which has allowed the scaling up of generative artificial intelligence, robotics, the metaverse and other technologies. It has been, and is likely, to continue to be very US-centric. Returns have been in the 15% to 25% range and include sectors (via indices) such as the S&P 500 Information Technology sector, the Nasdaq 100, specific growth indices, the Indian and Taiwan stock markets and, although less obviously and with more volatility, US small caps.

Global asset class performance 2009-2024

Non-tech stocks

For the bulk of equity assets returns have generally been better than bonds but not as exciting as the growth block. The ‘value’ block includes markets like Europe, the UK, Australia, and specific value indices. Returns have been between 5% and 15% with slightly less volatility than in the growth and emerging market equity buckets. Here investors can find more dividend opportunities with dividend yields in the 3% to 4% range, compared to less than 1% yield for most of the growth equity sectors. But for those who think current valuations in growth equities are not sustainable – which implies that current earnings growth cannot last – the value bucket might be a more comfortable place to be, offering more diversification and more income. Emerging market equities have been a disappointment in recent years. This includes the aggregated emerging market equity index as well as individual markets such as China, Brazil, Hong Kong, Korea and Mexico. A more protectionist world with higher interest rates has not been kind to emerging market equities. With the Trump agenda as it stands, this is likely to remain the case.

High returns from high yield

On the bond side the clear winners have been leveraged and high-yielding fixed income assets which sit right on the efficient frontier – the highest expected return for a given level of risk, or vice versa. Indeed, when I rank returns against realised volatility, high yield bond assets sit among the best quality investments with growth equities. This makes sense given the strong correlation between high yield and equity returns. What the long data series shows is that despite some shocks to the world economy (COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the end of quantitative easing), investors have been rewarded for taking higher levels of investment risk. Today we have some concerns about valuations in high yield and what that suggests for excess returns (the return above government bonds). But yields are still attractive, and outside of a duration shock related to an acceleration of global inflation, this remains an attractive asset class.

Duration has disappointed

For most of this period, interest rates have been very low. They went up in 2022 and that was a massive headwind for fixed income asset returns. Low income returns during the decade after the financial crisis and then a big revaluation through the monetary tightening has left long-term returns from long duration assets as some of the most disappointing, with returns from very long-duration government bonds being volatile as well. It is difficult to see that changing. Bond yields are higher but at around 4% for US Treasuries and UK government bonds – gilts - and around 2% for German Bunds, returns are not going to be exciting. The case for duration is therefore one based on hedging equity and credit risk, or looking for tactical above trend returns when the economy is weak. Over the period, the correlation of returns between the Nasdaq 100 and over 10-year maturity US Treasuries has been close to zero, and despite the experience of 2022, bond yields are now high enough to make a typical mixed equity and bond portfolio potentially less volatile than a pure equity one.

Range trading in rates

Interest rate curves remain the bedrock of valuation across financial markets and the best guess for the time being is that (official) rates are not going up. There are relative value differences between implied forward interest rates and current government bond yields and that will allow tactical trading of government bond assets. It is another consensus view that the 10-year US Treasury yield is close to fair value and will remain in its current range for the near future. Against that, UK gilts look more attractive today.

Income focus, with lower risk

The final group of assets is one I have termed as high grade and short duration credit. This is where returns are balanced between credit spreads and interest rate returns. This has meant a decent balance between return and volatility in recent years. Full market investment grade indices have delivered returns of around 5% in the US and UK and slightly less in Europe – albeit better and less volatile than government bonds. A short duration exposure has meant less volatility and slightly lower annualised returns. Given that credit curves are positively sloped, this is likely to continue to be the case. But for risk averse investors, short duration should be something that allows potentially restful nights.

Volatility stable

The other observation is of the 78 indices tracked, the current rolling one-year volatility of returns is lower than the long-term average for 70% of the sample. Asset returns from emerging market debt, high yield, UK, and European equities and even the Nasdaq 100 have been less volatile over the last year than their long-term averages. The recently higher volatility assets include most government bond indices, global aggregate, Chinese equities, and global inflation. Big changes in interest rate expectations (the market implied expectation for the June 2025 Fed Funds Rate has risen from 3% to 4% since the end of September) has transmitted to volatility in long-duration assets. Chinese equities have been volatile for their own reasons. It is striking that, despite all the geopolitical risks, volatility has been quite stable at the broader asset class level. On one hand this supports a tilt towards riskier assets but on the other suggests volatility is more likely to rise than fall and that probably means returns are compromised. It needs a macro shock for that to happen though.

Helpful but be aware

So it makes sense to use long-term risk and return data to dictate an appropriate asset allocation, depending on risk aversion, time horizon and return expectations. For now, that points to a growth and leveraged income bias. That could change and flexibility is key. If Trump unleashes US inflation and a growth shock in the rest of the world, it is going to get tricky. From the perspective of sitting in London, UK gilts are my risk hedge while short-duration high grade credit should outperform if we do see a risk-off period. However, the data also suggests if there is a market fall in response to some policy or geopolitical event, the medium-term recovery for high yield and growth equities would likely be strong.

(Performance data/data sources: LSEG Workspace DataStream, Bloomberg, AXA IM, as of 5 December 2024, unless otherwise stated). Past performance should not be seen as a guide to future returns.

5 topics