Make America tariff again

Key Points:

• Trump’s first two weeks in office have featured a flurry of policy announcements.

• Of most consequence to markets are tariffs, immigration enforcement and a government efficiency drive.

• On the positive side, Trump has committed to a deregulation agenda which will support business confidence, investment and hiring.

• So far, the market reaction has been muted, but we are monitoring the situation in case the outlook deteriorates on policy announcements.

Investors looked upon the election of Donald Trump with some scepticism, but had for the most part assumed (or hoped) that he would, on net, do more good than bad for American businesses. In his first term, threats of high tariffs and trade wars went mostly unfulfilled, while promised tax cuts were implemented. In this month’s Market Insight, we will review the first two weeks of the Trump Administration relative to investor expectations and what that means for markets in the year ahead.

Hitting the ground running

By design, it is hard to pass laws in the US. The Legislature and Executive are separate, unlike the Westminster system, meaning Congress, rather than the President, passes laws. There are numerous checks and balances, a Constitution limiting government overreach, the ability to filibuster in the Senate (obstruct progress), and the President has the ability to veto legislation. This "dysfunctional" system also means policy change tends to be gradual. This is generally seen as a good thing by businesses and markets.

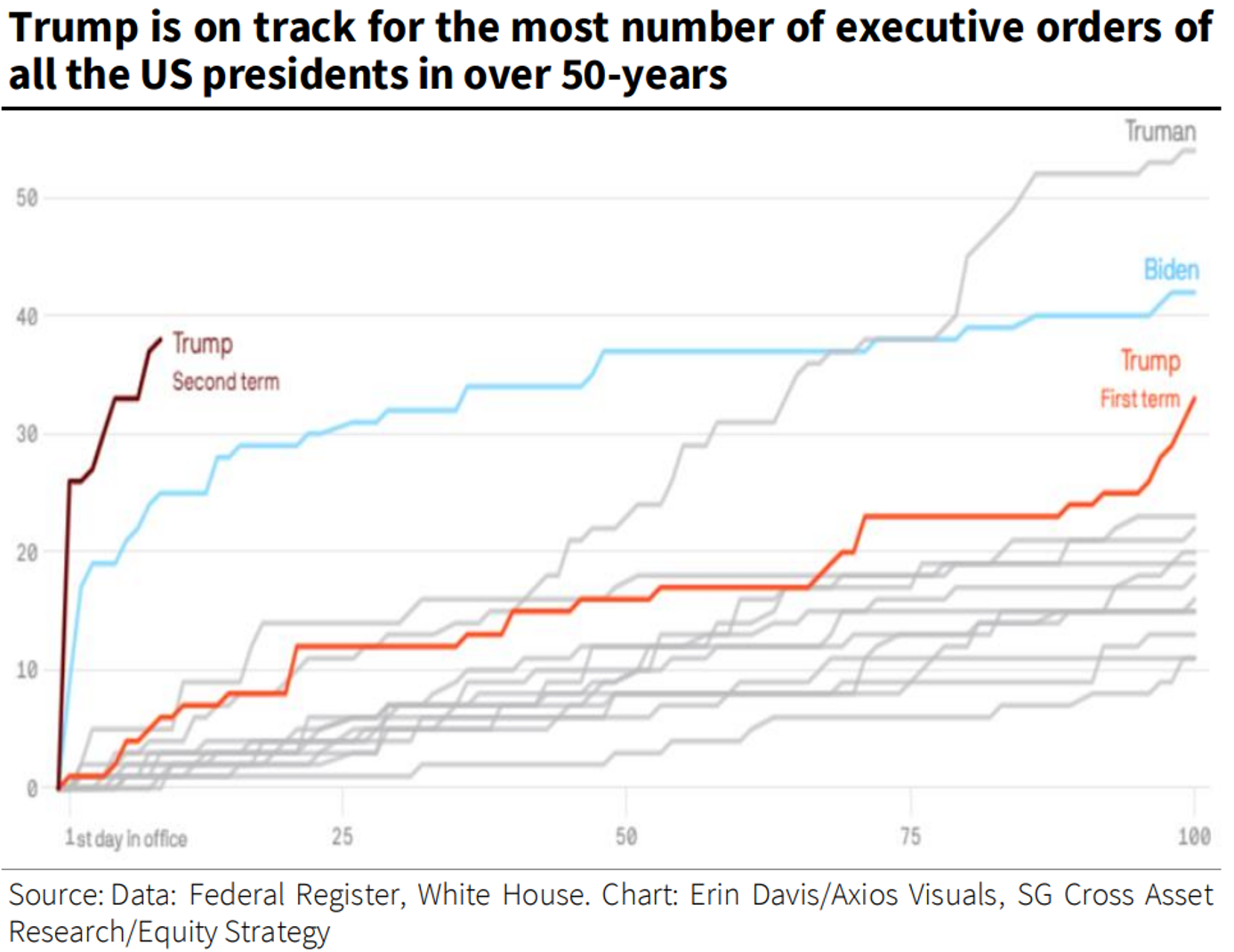

Administrations in the US try to get around these checks and balances by implementing change via executive orders, rather than legislating change through Congress. These attempts have a mixed track record of success. Executive orders may not be legal, or they may be simply overturned by the next administration. Still, that doesn’t stop presidents from trying and Trump has been no slouch in this regard, outpacing Biden significantly in his first two weeks. While many of these orders have not been relevant for markets, those that are haven’t been as strongly positive for markets and business as initially hoped.

Tariff man

After floating several different proposals since the election last year, Trump formally announced meaningful new tariffs on exports from Canada and Mexico (25%) and China (10%) last weekend. Then, maintaining his commitment to erratic policymaking, delayed those against Mexico and Canada for a month after their leaders made loose commitments to do something about border and drug control. The tariffs on Mexico and Canada were not expected by the market and were received quite poorly by the business community. Many US based manufacturers have supply chains that cross borders. Indeed, the mid-1990s NAFTA agreement was intended to integrate economic activity between the three countries and by all accounts has been quite successful. The tariffs against China remain in place (at the time of writing), but where they eventually land is anyone’s guess.

The initial negative market reaction to the announcement was moderately negative, with equity markets selling off around 2%. However, this reaction has for the most part faded, likely reflecting the delay in those against Mexico and Canada – implying a “deal” will be struck by Trump – similar to the progress of the 2018 US / China trade war.

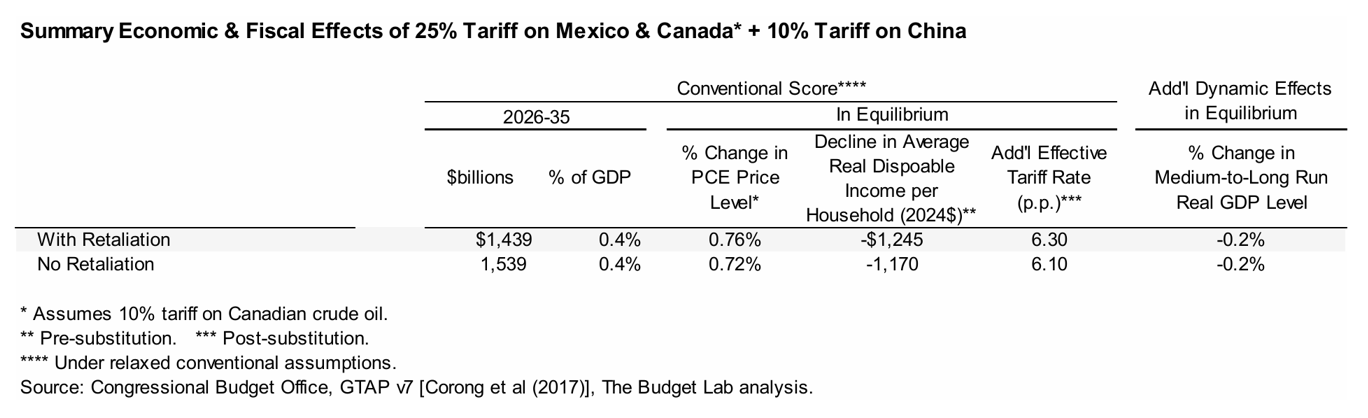

Another reason the market reaction has so far been muted is because a lot of the hysteria around tariffs (in 2018 some were calling for a repeat of the Great Depression if a full-scale trade war erupted) has fallen away with time. Tariffs aren’t magical. They are a tax on imports, the costs of which will be borne by some mix of consumers or producers depending on the sensitivity of supply and demand to changes in price. Like taxes on income or consumption, they are inefficient. Cross border supply chains will need to be adjusted, making goods more expensive to produce. Like a GST, they also increase the absolute price paid for a good, so they are inflationary. Because they make goods more difficult to produce and more expensive, households and businesses consume less of them, meaning economic growth is lower than it otherwise would be. The table below shows the estimated economic and inflationary impact from the announcement. The economy is a little bit smaller, inflation is moderately higher and households are generally poorer.

In a perfect world, there would be no tariffs (or income or consumption taxes). However, we don’t live in a perfect world. Proponents of tariffs argue that we need specific trade policies to (1) offset the impact of the trade policies of other countries and (2) affect outcomes which, while damaging to the economy, are beneficial for society. The former is a bit of a long bow to draw. If China wants to suppress the living standards of its population in order to sell cheap electric vehicles and TVs to consumers in other countries, best of luck to them. The latter argument has more legitimacy.

As countries become richer, they tend to produce more services and less goods. Many of the most successful companies in the US (and the world) are technology companies, selling data and experience. Our clothes, cars and toys tend to be manufactured in poorer countries because labour is cheaper. That makes households wealthier, but it does make an economy less resilient – or at least more reliant on its trading partners. In a normal environment, this doesn’t really matter. However, if there is an eventual conflict between China and the US, throwing research reports at the enemy won’t be particularly effective. In a protracted conflict, it is highly questionable whether the US and its allies could produce more missiles, ships and drones than China. The next war will also be fought over networks as well as land, sea and air. China might produce quality, cheap computer chips, but you don’t want them installed in anything that matters for national security. Nor their software. Both could open back doors into nationally important networks such as power grids and communications. To the extent tariffs and other industrial policies address national security concerns by reshoring manufacturing capacity, they are legitimate (and some may argue necessary). We just need to be aware of the price – households are a bit poorer than they otherwise would be.

Department of Government “Efficiency”

No one who has ever had anything to do with the Government would complain about the establishment of a Department of Government Efficiency. “DOGE” was set up as one of Trump’s initial executive orders and has a remit to modernise the Government to drive efficiency and reduce waste. What that means in practice is yet to be seen. Most of what has been announced so far has involved the cancellation of diversity, equity and inclusion related positions and contract. Trump has also offered around 2 million government workers a quite generous voluntary redundancy package. We have our doubts that outsiders can be parachuted into Government and in a relatively short period of time reorganise (or make efficient) an institution more than 230 years old. Regardless, if DOGE is to any degree successful in reducing “waste,” that will likely be short term negative for economic growth. Waste is still government spending, and reducing waste is essentially fiscal austerity. We can look to Europe in the post Financial Crisis period for an example of how government austerity effects the economy. While it may be positive, or even necessary, for medium term productivity and fiscal sustainability, the journey to that point is always painful. As a result, we are keenly watching this area as it has arguably more significant ramifications for short term US economic growth than the current tariff proposals.

Lifting the Regulatory Boot

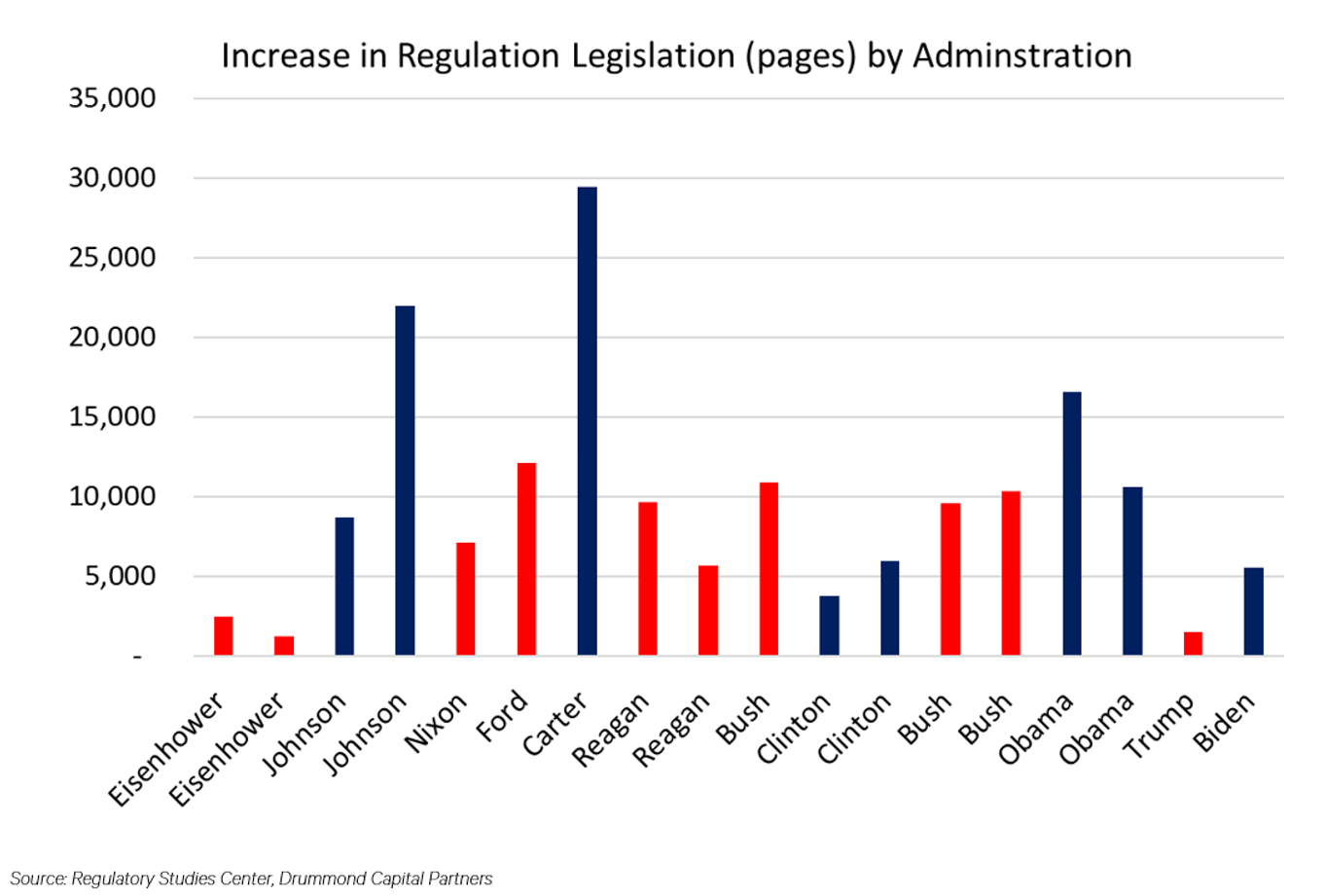

Sometimes doing nothing is the best thing you can do. That is not a philosophy readily adopted by Governments. Being regulated is a costly experience for a business and for the economy as a whole. Estimates of compliance costs for the US range between $300 billion and $1.7 trillion per annum. Undoubtedly small business bears a disproportionately high cost per employee of this burden. We think that is part of the reason why, despite the apparent craziness at the headline level, businesses in the US like President Trump (particularly small business based on sentiment surveys). Republican administrations, and Trump in particular, have a much better track record than Democrats on this front (see below). Trump has a deregulatory agenda. Even if he fails to reduce the overall regulatory burden, he is unlikely to add to if at anywhere near the pace of the Biden or Obama administrations. This is positive for markets. Whether it is positive for society as a whole will depend on individual political leanings.

Close the Borders

Another key focus of the Trump Administration has been stricter enforcement of border controls. Paying illegal immigrant workers below market or minimum wages has long been a feature of many sectors of the US economy, particularly construction, hospitality and agriculture. While there are ethical and productivity implications of this workforce structure, at the end of the day it leads to lower input costs and potentially higher profitability for the business (particularly small) sector. In addition to lower labour costs, immigrant (including illegal) workers have a long track record of working hard and building successful businesses. As do their children. People don’t march through the desert carrying all their possessions on their back, putting their lives at risk and starting over again to be lazy when they arrive. They are a key part of the American success story.

Again, this is a highly political topic, but from the perspective of the economy and markets, it is likely a net negative assuming Trump actually follows through.

Portfolio Positioning

So far, the net market reaction of Trump’s policies has been muted. Perhaps his tariff threats are not seen as credible or perhaps the expected impact on the economy is not sufficient enough to offset currently strong growth, particularly in a deregulatory environment. At the very least, if the tariffs are eventually enacted we would see them as inflationary enough to keep the Federal Reserve on hold for most of this year. If tariff revenues are recycled into stimulatory tax cuts, potentially the market narrative will shift towards rate hikes if inflation and growth rise.

Our portfolios are currently slightly overweight growth exposure, with a bias towards international equities over Australian equities and domestic floating rate credit over government bonds (which are more sensitive to higher inflation and interest rates). We are continuing to assess Trump’s policy agenda, and will make changes to the portfolio accordingly.

2 topics