Make income great again

We recently had a visit from a CEO of a major mining company, asking us a range of questions. Much of it was to do with M&A strategy. At one point, he asked to what extent should market prices be relied upon as the ‘true’ value of the group. The question at one level is easy to answer for an active investor – we have no value proposition if we do not believe that persistent market inefficiencies exist, which are capable of being exploited. In our case, we believe that the basis for that exploitation is that ultimately share prices, whilst in the short term often buoyed or depressed, revert to fair value. At another level, though, the concept of fair value is increasingly being questioned as “expensive” stocks march ever higher, as again they did in January. Is the whole concept of valuations now redundant in pricing assets?

In our view, perhaps unsurprisingly, the answer is no. But, with some important caveats. Generally, management intent is as critical as ever in realising value potential, as highlighted in several examples where that has occurred, is occurring and hopefully will occur. In each case, management intent and action is visible; passively expecting profits to revert to historic norms is clearly unrealistic. Secondly, growth needs to be well defined; ultimately, growth in revenues counts for little if it can’t be converted to free cashflow, sustainably. Dominos presents a terrific case study of an ASX listed stock traversing through investor hope and reaching reality, whilst profits remained reasonably stable. The DeepSeek imbroglio also reveals some of the travails often overlooked by the market in assessing the quantum and, more importantly, duration of excess cashflows. Finally, the role of Dirigisme – government interference, sometimes foreseen but often not – in assessing these sustainable free cashflows is as fraught an exercise as it ever has been, with government of all persuasions finding that choices, revealing fiscal winners and losers, need to be made.

A little more than two years ago, Boral (ASX: BLD) recruited Vik Bansal as CEO. Now fully owned by Seven Group (ASX: SVW), the management intent to decentralise decision making and improve efficiency and effectiveness has seen profits and cashflows improve to the point where Boral is now well on track towards making 15% EBIT margins (and 10%+ returns on assets) after struggling to reach 10% EBIT margins (and 5% RoA) in any year through the prior decade. This followed the precedent in restoring sustained profitability to Australian manufacturing companies set by Paul O’Malley at Bluescope (ASX: BSL) a decade ago, an ethos that has been followed by his successor Mark Vasella. The pain Bluescope went through in restructuring the business to provide it with a base from which to make even better returns than Boral has been well documented, but with recent growth in the domestic cost base the risk is that, to some extent, the lessons are being lost with time. In contrast, Australia’s only makers of double glazed glass, Oceania Glass (formerly Viridian), went into administration several days ago, citing energy and wage inflation, and dumped product from China (and delays in the imposition of tariffs by the Anti-Dumping Commission) as causing its demise.

All three products are essential inputs into “growth” sectors. There can be no increased uptake of data without data centres, and no new data centres will be built without concrete, steel and glass. It is impossible for the former to have record high (and increasing) margins with long duration, and for the former sectors to have secularly pressured profits, let alone be insolvent. This is especially so, as is the case with concrete, where there are legitimate logistical barriers to imports; cement which is subject to moisture in transit tends to be of little use to any end buyer. Pricing reflecting next best alternative as a substitute material, together with a splash of management intent in looking to differentiate product and service and price for value, has seen shareholders in Boral (and now Seven Group) reap rewards through the past three years, and Bluescope for the past ten. Other concrete producers listed on the ASX haven’t yet got the memo.

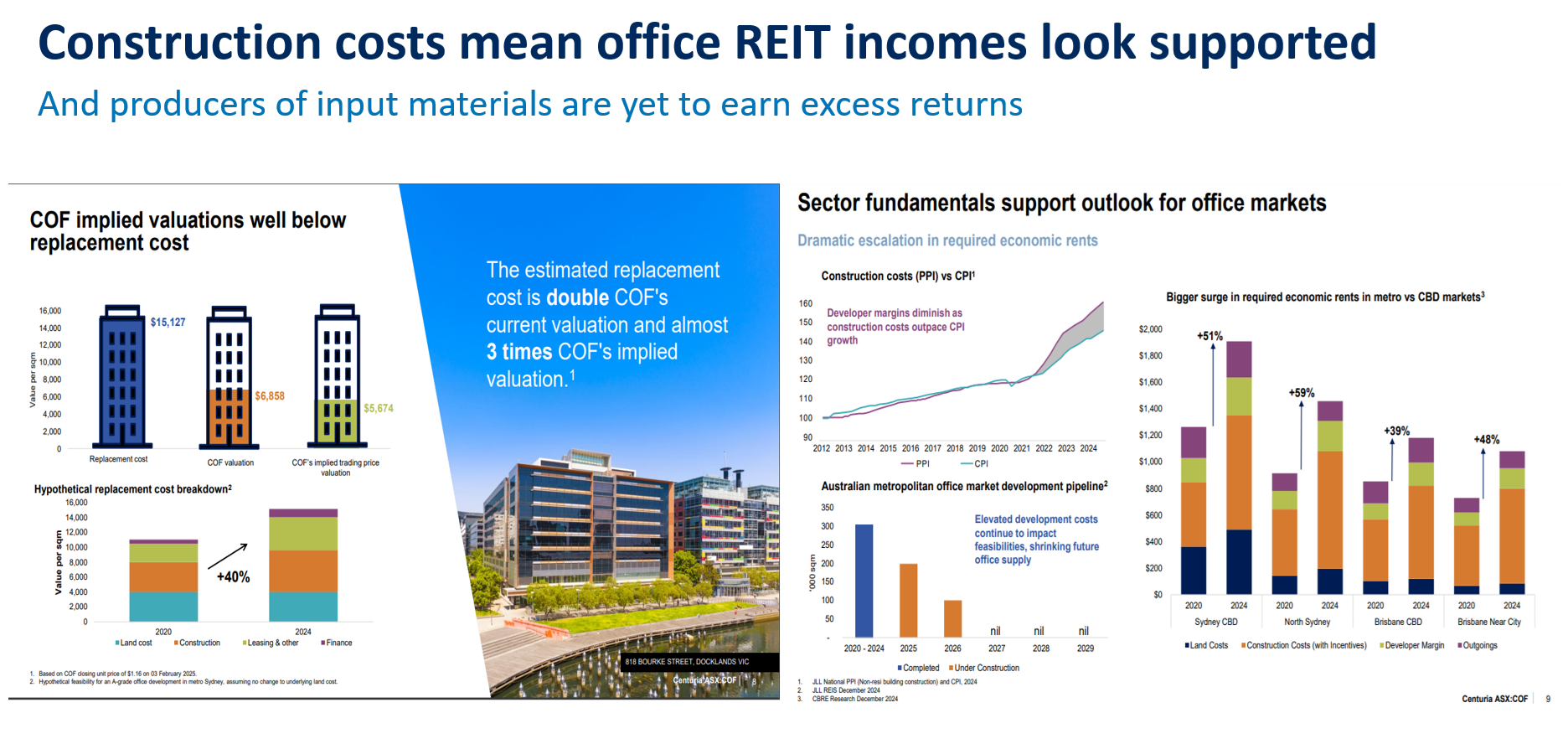

Apart from being essential inputs into data centres, all three products are also required to construct a new office tower. As Centuria Office REIT (ASX: COF) highlighted in their results presentation, office assets are now trading at circa half replacement cost given the increase in materials costs in recent years; and yet still trade below book value. Unsurprisingly, no supply is slated in the Australian metropolitan market for the next several years.

Source: COF Results Presentation HY25

The market value in Dominos (ASX: DMP), having dropped 80% from the heady highs in the middle of lockdowns several years ago, when growth in unprofitable locations was seen as presaging future riches, responded to a strategy pivot; make income great again. The share price rose 20% the day announced a MIGA strategy, i.e. curtail loss making activities. These same loss making activities were seen as the engine for growth by investors but four years ago, when the Dominos multiple rose to 75 times when EBIT was $270m. For context, the group is now forecast to make EBIT next year of $250m; the $12b fall in value through recent years was a response to less than a 10% fall in earnings. Several ASX listed stocks which currently make operating losses but enjoy market favour on the promise of future riches from those same activities may do well to examine the Dominos case study. This examination could also be undertaken by the currently brow beaten mining CEO. Perceptions of growth prospects can and do change materially, and quickly; far more quickly than profits themselves can usually change.

The hard and sustainable route to changing perceptions of future profits and cashflows – as reflected in the Bluescope, Boral and Dominos examples – are currently in nascent form in some other companies and industries in our portfolio. Both Orica (ASX: ORI) and Incitec (ASX: IPL) are in a position where the returns on their assets are low, especially on a replacement cost basis for their domestic assets, and yet there is little likelihood of new capacity being added; just as is graphically depicted in the Centuria REIT chart for Office property. Especially in the case of Incitec, new management have expressed a strong intent to improve returns. We expect the same to come from some other holdings across different industries we have, for example Ramsay Health Care (ASX: RHC), Seek (ASX: SEK) and Woolworths (ASX: WOW). In each case, returns have suffered after prolonged periods of malinvestment earning poor returns, and in each case management have every incentive to improve that paradigm.

The best thing the Australian banking sector has done for itself in a global era of dirigisme has been to avoid the scourge of dirigisme, or increased government regulation.

It was Brad Banducci, not Peter King (or any of Mr King’s banking peers), in Canberra arguing whether return on equity or return on funds employed (or even assets for a bank) is the right metric for outsiders to focus upon as a proxy for whether or not the company / sector is making excess profits. In turn, the ever sensible Matt Comyn, CEO of CBA (ASX: CBA) and hence the bank with the most to lose from any potential emergence of dirigisme in the Australian banking sector, quickly reversed course when CBA flagged the prospect of a $3 fee for a branch withdrawal, for only one account held by only 1m customers, only 10% of whom undertake branch withdrawals. Mr Comyn publicly revealed he was unaware of the proposal until it was revealed in the press the following day. The proposed fee was quashed with three hours and CBA publicly apologised. A fee potentially raising circa $500,000 per annum was not going to be allowed to derail a $270b market capitalisation, for a bank trading four standard deviations expensive.

Mistakes will always happen, but this was a great example by a large company in quickly rectifying it in order to avoid any unintended political scrutiny and, potentially, worse. This level of self help has been absent from some of CBA’s competitors in recent years, most notably ANZ (ASX: ANZ), and the sector will be put to the test again this year with the mooted sale of HSBC’s Australian banking business, which is only sure to bring with it to the buyer an envelope headed “Buyers curse”. That envelope will come no matter the price paid for the asset, given the poor history of in market mergers in the Australian banking market. The banking sector remains our biggest underweight. This has been painful as the sector has aggressively outperformed, led by the banks with the highest multiples, and despite pressures in small business solvency there is little yet in the way of credit losses stymying profits.

Execution takes many forms but having a sustained congruence of purpose and an intent in skilling those entrusted in bringing that purpose to a commercial outcome cannot be understated. For example, the establishment of the Denison Miller Academy, named after CBA’s first CEO, saw younger CBA executives trained by globally renowned strategy and leadership Professors in Sydney, using CBA case studies. It has spawned much executive talent not just for CBA, but also its competitors. Several years ago, one major competitor recruited a head of Retail banking, head of Institutional banking and a head of IT, all from CBA, within a year of a different person being appointed to those positions within CBA. As is almost always the case with lateral hires, the (corporate) body rejected the transplant; CBA continued to outperform. Cultural change is hard, which is another reason why valuations can only be realised when accompanied by management intent; rarely will mean reversion in itself be enough to change the market performance of a company subject to persistent poor operational and capital allocation decisions.

Equally, on the other side of the equation, and was evinced during the month with the rise and fall of the perception of DeepSeek as a disruptive force in all things AI related, to maintain high returns for long competitive advantage periods is just as hard. Indeed, all of the CEO’s of the major US IT companies have reinforced the themes illustrated by the ASX listed old world examples we have touched on in this commentary, when assessing the impact of DeepSeek on their own business through the past several weeks. As Jeff Bezos put it many years ago “Your margin is my opportunity”; in turn, Satya Nadella of Microsoft spoke to the lesson of DeepSeek being that AI is going to be “commoditised” on the back of competition. On the Meta earnings call, Mark Zuckerberg played the Dirigisme card; “there’s going to be an open-source standard globally … and I think for kind of own national advantage, it’s important that it’s an American standard”. The Google CEO, Sundar Pichai, spoke to the importance of being the lowest cost producer:”… A lot of it is our strength of full stack development and our obsession with cost per query. I think part of the reason we are so excited about the AI opportunity is because the cost of using it is going to keep coming down, which will make more use cases feasible”.

Ultimately, as Bluescope, Boral, and Dominos evince; and Incitec, Ramsay, Seek and Woolworths hopefully will, growth only matters if it is realised in cashflows.

The market may frolic with expectations of future growth for some time, but few examples exist where that is sustained, in any industry, over time. Even with AI, taken at their word through the past several weeks, the CEO’s of the major Tech companies in the world agree their industry will likely be subject to the same forces, where capitalism sees excess returns competed for. Markets are always seeking the potential for those excess returns to a greater extent and for a longer period of time than has been experienced before, and the current lust for this paradigm is as great as it has ever been. Which is why multiple divergence is as great as it has ever been. Unlike the Mining company CEO, and the more favoured ASX cousins currently enjoying the favour attached to anything AI related, we suspect the wrong thing to do would be to assume that the equivalent of Dominos at 75 times earnings is a perpetual state.

Market Outlook

At a risk free rate of 4% or more, most assets are currently expensive, unless they can produce sufficient real growth to grow into stretched multiples, which has always proven hard to sustainably achieve and hence is a scarce asset which should be prized. All the more so after an extended period of rerating, the market clearly does this; the question is whether it is being appropriately priced, in the absence of corporate magic. For businesses with large investment requirements and/or labour forces, the emergence of inflation has only made the attainment of real growth even harder, and few have proven up to the challenge. Consequently, our portfolio remains more focused on capital preservation than capital appreciation. The best prospects for capital preservation are unlikely to be the stocks and sectors which have benefited most from aggressive recent re-ratings, especially if earnings growth continues to be deferred, as in the case of the financials sector. Increasingly, founders/insiders/large shareholders appear to agree with us, as large stakes are sold in some of the best market performers. It would appear they agree with the CEO’s of the magnificent 7; to assume excess returns for an extended period, especially in the face of significant capital being applied to the sector, is heroic. Far more likely through the passage of time is that investors’ hopes prove to be mostly mislaid, and that ultimately productivity growth needs to be achieved for high ratings to be sustained.

Learn more about investing in Schroders' Australian Equities.

12 stocks mentioned