Mission Impossible: Will global central banks nail the "soft landing"?

First, it was "unprecedented". Then, it was "transitory". When that left the airwaves, US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell told us all to "retire" the word in an admission that the central bank had completely underestimated the lasting impact its stimulus would have on the state of consumer demand in America.

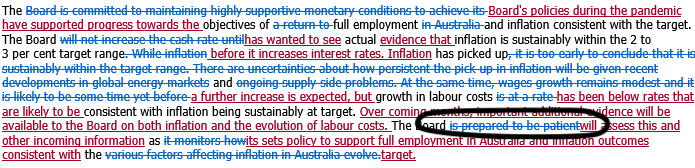

Finally, "patient" was the word among the top brass in business - how long are the experts willing to wait out any surges in inflation? This term fed through to Australia where the RBA used that word in its monthly statement for many meetings until April this year when it finally threw in the towel.

Yet through it all, markets could count on the so-dubbed "Fed put" - a theory where the Federal Reserve's words and actions could swoop in during down days on the market to protect your gains.

That all worked out until investors and traders became way too used to the luxury, and now, many analysts argue we are seeing the effects of that runoff.

Now, the buzzword to end all buzzwords is "soft landing". Global central banks, led by the Federal Reserve, will do this their own way but all will face the same problem.

How do you cool scorching hot inflation without blowing up demand?

This wire will take a look at the "Mission Impossible" ahead of monetary authorities around the world, plus feature insights from some of the best in an attempt to explain the likelihood of all this coming to fruition.

But first, a brief history

The term itself "soft landing" could be likened to how an aeroplane touches down after a long, turbulent flight. Do you want it to touch down with a great big thud or as smoothly as possible?

If the answer is the latter, that's exactly what the Federal Reserve (and their global counterparts) are trying to do.

The hope is that by inducing a perfect amount of market manipulation, interest rate hikes, and other means, global monetary authorities can commence a cyclical slowdown in economic growth while avoiding a recession.

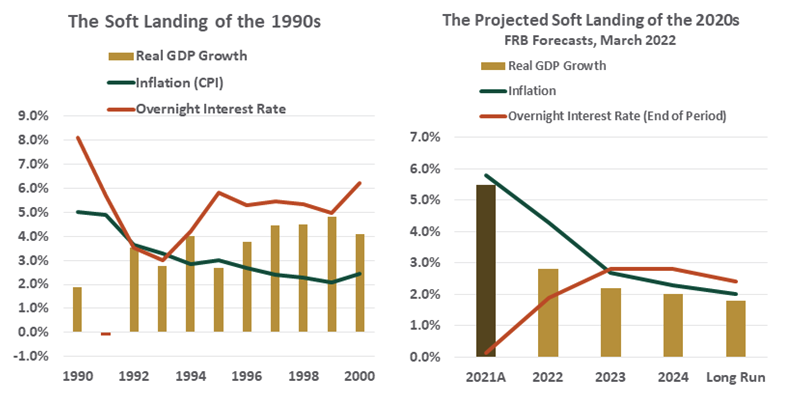

The term was first brought up during the tenure of former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan, widely credited with engineering one in 1994-1995.

Under Greenspan, the central bank doubled interest rates to 6% and succeeded in slowing economic growth without killing it off. While it didn't end perfectly, it is still considered by investors as the one major time the central bank did create the soft (ish) landing.

So they managed it one time. What happened every other time?

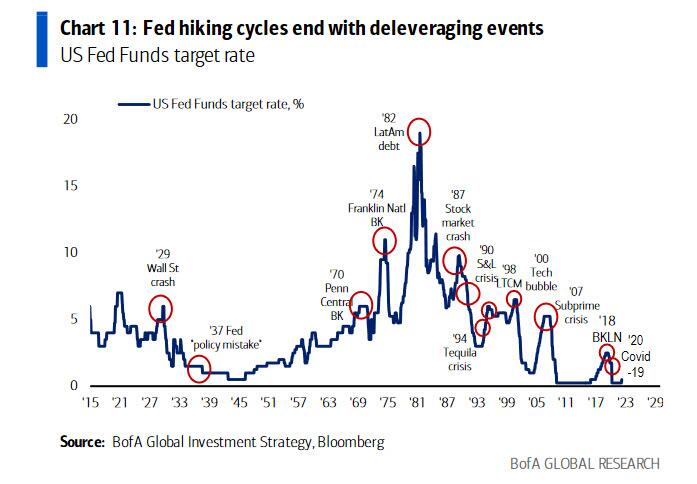

I could write a long-winded explanation but I'll let this chart from BofA do all the talking.

The chart is simple to interpret - every time the Federal Reserve has had to hike rates to cool inflation, it has led to a major deleveraging event. Some are very familiar to all of us - the 1929 Great Recession, Black Monday in 1987 and of course, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

Some of the other events are a lot more contained to the United States but the problem remains the same - how do you hike rates without bursting the bubble? That's the (extremely unenviable) task that now faces Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and friends.

Speaking of Mr. Powell, he did (once) suggest the Fed was on course for another of these soft landings in 2020 given their system for evaluating progress on inflation was about to change after years of missing the target band (2-3%).

Low inflation seems to be the problem of this era, not high inflation. Nonetheless, in the unlikely event that signs of too-high inflation return, we have proven tools to address such a situation. (Powell speaking at the Jackson Hole symposium in 2019)

Only time - and the data - will tell if he gets there this time.

Skeptical and concerned

After inflation became "transitory" in the Fed's eyes, global economists began to split into two - those who thought the Fed was right and those who think they are completely wrong.

For those in the latter camp, they seem to have been vindicated if the data is purely the judge. They have argued the Fed waited too long to address mounting price pressures by using out-of-date models that have underestimated the impact of inflation day-to-day. Russia's invasion of Ukraine was the final straw.

One of those who vehemently disagree is Matthew Nest of State Street Global Advisors who wrote this in a recent outlook report:

It seems that the only way the Fed can engineer a soft landing at this point is if inflation eases in short order, allowing the Fed to ease off the brake.

In March, Lisa Shallett, CIO of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management went one step further - and how right she ended up being.

...We have a rather muddy outlook, with possibly greater risks to the Fed’s efforts. The "buyable bottom" in equities is not yet here, in our view, and when it arrives, opportunities will be found in new market leadership.

So it appears there are fewer and fewer who believe they can stick the landing. Least of all are Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs - both of whom were early on the street with their recession calls.

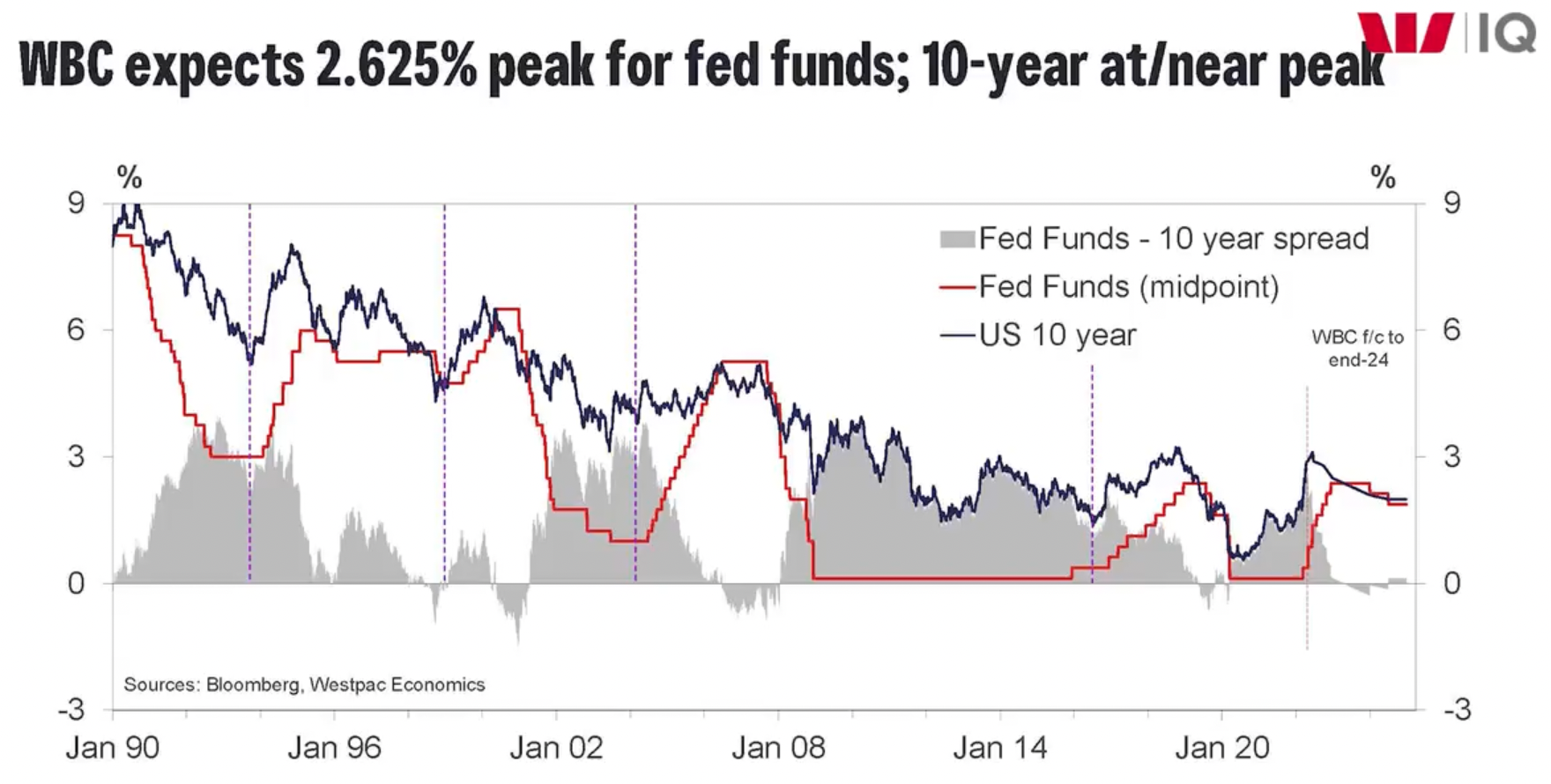

Finally, some perspective on the risks from Elliot Clarke at Westpac Institutional Bank. In a recent video, Elliot noted that the result of this soft landing will be pretty much dependent on the war in Ukraine and how the recession affects main street.

The key risk to this soft landing expectation is a further escalation in global conflict, with consequences for supply and expectations for wages.

This, in turn, informs their view that the Federal Reserve's terminal rate is lower than most other analyst expectations as this chart shows.

Perspective from Matthew Sherwood, Perpetual Asset Management Australia

It wouldn't be so unlikely if rates were not so low - that's the main thesis from Matthew who says the low base will be the biggest problem for central bankers.

"Real central bank policy rates are twice as low as the rate at the equivalent stage of the post-GFC cycle. Accordingly, central banks need to jack rates up a lot, and do it very quickly, which raises recession risk, so the odds of a soft landing are much lower than normal," Matt says.

The other biggest problem for Jerome Powell and his friends is the time lag. Economic theory suggests there is a gap between the time policy is announced and the time for policy to be felt by businesses and consumers on the ground. For monetary policy (that is, central bank action), that time lag is usually 18-24 months. That alone has also made Matt very nervous.

So where can you play defence? Matt argues that the answer is probably not the same response it's been for more than 120 years.

"Investors need to working on their portfolio defences and determine how to diversify equity risk in a world where bond yields may not perform this task as well as it has for the past 120 years," Matt says.

"This includes using our bought put options, safe-haven currencies and potentially a higher than normal cash weighting."

Perspective from Tim Toohey, Yarra Capital Management

Tim has an equally unpleasant view of the great central bank unwind - though he does credit part of the problem to bad luck and partly to poor policy choices.

"Choosing to deliberately wait until after inflation had exceeded their target levels will, in time, be viewed as one of the poorest central banking strategies in the post-war period," Tim says.

However, not all economies are created equal and Tim actually thinks Australia will fare the best out of most G10 nations because of the world's reliance on our commodities.

Purely our luck, Tim thinks, will shield us from bigger problems overseas.

"Combined with a large bounty of excess household savings and sizeable wealth buffers to draw upon, Australia is best placed of the developed nations to achieve a soft landing, albeit global downturns have a habit of rapidly being mirrored locally," Tim says.

So how is Tim investing in these times? He is moving into bonds but not buying the equity market dips just yet.

"I think it is sensible to wait for the further value to emerge," Tim says. "There will clearly be an opportunity to rotate portfolios later in 2022, as fixed income markets have priced for far too many hikes than central banks are ultimately likely to deliver. But for now, quality companies with defensive characteristics are likely to trade a premium to the rest of the market."

One more note: Chart of the Week

My chart of the week comes from Northern Trust's Carl Tannenbaum. Carl penned a piece last week on the data's trajectory and made some interesting conclusions about the true likelihood of a "soft landing".

With a nod to Disney's The Lion King, he noted that a soft landing is not felt evenly across the economy - or for that matter, against other economies. Fed tightening cycles are usually no good for emerging market investments. The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have also made matters worse for these economies making the ripple effect that much more pronounced this time.

As he points out, the difficulty is much higher this time. Carl's thesis is that 1994 provided a lot of good fortune (no war, no pandemic, and most importantly, speedy reaction to the data) for Greenspan. The Fed of today must chase its coattails, nail the soft landing, navigate all the above headwinds, and do it all in an election year.

I frankly don't envy them.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

I'll be in charge of asking the questions to Australia's best strategists, economists, and fixed income fund managers. If you have questions of your own, flick us an email: content@livewiremarkets.com

3 topics

2 contributors mentioned