More Trump tariffs (and deals) – implications for investors and Australia

Trump has followed through with his threat since last November to impose 25% tariffs on Canada (except energy which is 10%) and Mexico and a 10% tariff on China. This was originally set for a 4th February start.

But with Trump agreeing to a one month delay to the tariffs on Canada Mexico subject to border and drug conditions, its possible a deal may be reached to avert or cut the tariffs, but uncertainty around them and the threat of other tariffs means market volatility will likely remain high. This note looks at the implications, including for investors and Australia.

If implemented the tariffs are much bigger than 2018

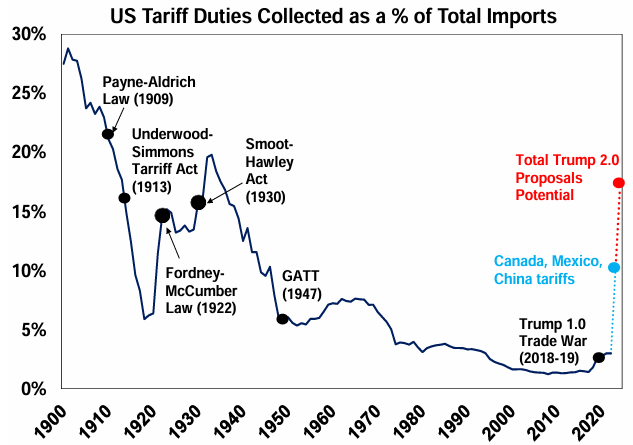

42% of US imports (5% of US GDP) come from these three countries and rough estimates are that these tariffs will add 7% to average US goods tariffs taking them to around 10% which is the highest since 1946, much bigger than the 2018 tariffs. See the next chart.

What’s more Trump is continuing to signal even more tariffs ahead. He has ordered a review of unfair trade practices by 1 April, continues to talk of a general tariff on all goods which in the election he put at 10% or 20%, has talked about a 50% or 60% tariff on China and is vowing to impose tariffs on the EU (“pretty soon”), semiconductors, steel, metal, oil and gas and pharmaceuticals. In total, Trump’s proposed tariffs could take the average US tariff to near 20% or more, its highest since the 1930s!

But will the tariffs stick?

Who knows with Trump! He is known to use tariffs for bargaining. We saw this with a 25% tariff recently on Colombia, and Mexico in 2019 both in relation to immigration but they were quickly removed after they did what he wanted. And he has already agreed a delay with Canada and Mexico adding to the view that its mainly about negotiation.

Perhaps he felt he had to “kill some chickens to scare the monkeys” so the whole world knows he is serious before then making deals. And Trump’s use of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act to implement the tariffs could see them challenged legally. So maybe they are never implemented, particularly on Mexico & Canada.

But the Trump Administration has also referred to tariffs as aimed at reducing America’s trade deficit, serving to bring production back to the US and being a source of tax revenue to fund personal and corporate tax cuts. If this is the case tariffs may be more of an end point rather than a case of “escalate to de-escalate” and we may have a long way to go yet.

Our view remains that a sharp fall in share markets (maybe this helped drive the delays to the tariffs on Canada and Mexico) and political damage caused by cost-of-living increases faced by ordinary Americans from the tariffs will ultimately see them removed in some cases or scaled back or end at levels lower than he has been talking about.

But there’s likely a way to go before we get to that with Trump seeming not concerned about Americans having to see “some pain”. In 2018 shares had a near 20% fall due to the trade war and Fed hikes before Trump got concerned.

What is the likely impact on the global economy?

The tariffs so far announced if implemented will mean a modest and hopefully temporary hit to global economic activity due to disruption to supply chains and export demand Canada, Mexico, China and the US. A rough estimate is that the tariffs so far announced would cut between 0.4-0.9% from US GDP this year, will likely push Canada and Mexico into recession and could knock about 0.5% from Chinese GDP.

It could be more with retaliation. It’s possible China responds with more policy stimulus which it’s been keeping in reserve to support its economy, but it’s also at risk if Trump ramps up the China tariff to 50-60% as he has threatened in the past.

Rough estimates suggest the tariffs would add around 0.4-0.8% to US core (ex energy and food) prices this year. This along with the threat of more to come risks the Fed holding off on further interest rate cuts.

Its also possible countries hit with US tariffs, including Europe, respond more aggressively with rate cuts as they see more of a hit to growth than a boost to inflation, unlike the US. But this depends on how aggressively they retaliate in raising tariffs and how far their currencies fall.

But Trump has said tariffs won’t add to US prices?

Trump has long argued that tariffs are “a tax on a foreign country” which has a tariff imposed on their exports so they pay it. This is gobbledegook – like his claims that DEI caused the LA fires & the Washington plane crash!

A tariff on an import is paid by the importer at point of import. Suppose a good costs $US100 to import to the US and retails for $US200 after some more production, transport costs and retail margins. A 25% tariff would see the cost to the importer rise to $125. He or she could choose to absorb the $25 in his or her profit margin, ask the foreign exporter for a lower price or pass it on to whoever it is sold too.

If it’s all passed on then the end price of the product to the consumer will rise to $US225, an 11% rise. The reality is likely to be some mix of these, which depending on the size of the pass through will boost the price to Americans.

Part of a price increase to US consumers may occur because as the price of the import goes up buyers will switch to American made alternatives, assuming they are available, but this will be at a higher price as otherwise imports wouldn’t have found a market in the US in the first place.

A rise in the relative US price of an import is the whole point (apart for forcing geopolitical aims) of imposing the tariff in the first place, i.e., to force US producers and consumers to switch to American made products. And of course, if the Trump goes too far in boosting tariffs there will be no imports and no tax revenue from tariffs!

What does it mean for Australia?

For Australia, the direct impact of Trump’s tariffs should be minor, but it is vulnerable to an indirect impact which could result from a fall in global trade and less demand for our raw materials from China.

Exports to the US are only 4% of Australia’s total exports and may be spared from Trump’s tariffs as Australia has a trade deficit with the US, but they could still be hit if Trump’s motivation is mainly to shift production back to the US and raise tax revenue.

Our main US goods exports are beef, precious metals, pharmaceuticals, aluminium, aircraft parts and wine – some of which Trump is specifically talking about putting tariffs on.

However, as an open economy with high trade exposure to China, our main vulnerability is to a fall in global trade flowing from a trade war sparked by Trump’s tariffs, particularly if it weighs on demand for Chinese exports.

An OECD study showed that Australia could suffer a 1.2% reduction in GDP as a result of a 10% reduction in global trade between major countries (which would be an extreme outcome). Resources shares would be most at risk.

Other analyses cited for example by RBA Deputy Governor Hauser in a speech in December suggest that allowing for shock absorbers like a fall in the $A the impact on the economy could only be 0-0.2% over two years.

As Deutsche Bank points out, part of the reason for a potentially small impact on Australia also flows from the fact that Australian exports are dominated by mining, which is only a small share of manufactured end products that go to the US compared to exports from most other countries including Canada, Asia, Europe & Japan.

Of course, similar fears existed during the last Trump trade war, and it didn’t turn out so bad (although the $A fell 13% in 2018 with US tariff hikes and Fed rate hikes). And there would still be demand for iron ore somewhere – it just may switch from China to elsewhere.

Much will depend on how hard Trump goes, how other countries respond and how long the tariffs remain in place. US tariffs won’t add to Australian inflation unless Australia imposes tariffs on US products in retaliation or the $A plunges.

RBA Deputy Governor Hauser argued that the impact on inflation from US tariffs is ambiguous with disrupted global supply chains offset by somewhat lower demand and potentially more cheaper goods finding their way to Australia.

So in terms of the impact on RBA monetary policy, our assessment is that Trump’s trade war adds to the case for a rate cut because it’s more of a threat to growth than inflation.

That said, the weak $A is one factor that will likely slow the pace of easing likely seeing the RBA cut in February but hold in April to avoid pushing it down faster. This is consistent with the money market’s assessment that saw the probability of a February rate cut rise to 96% after the tariffs were announced.

What does it mean for investment markets?

Given the hit to economic activity and boost to US inflation potentially resulting in higher US interest rates than otherwise, Trump’s trade war is:

- negative for shares – probably foreign shares more than US shares;

- positive for US small companies versus US large companies as they are less likely to be impacted by the trade war

- ambiguous for US bonds (due to weaker growth but higher inflation) but positive for other countries bond markets (due to weaker growth and possibly more rate cuts);

- positive for the $US (as tariffs tend to push up the currencies of countries imposing tariffs) and negative for other currencies;

- while its negative for the $A versus the $US, other currencies subject to tariffs are likely to fall more; and

- potentially positive for gold as a safe haven.

Of course, some of this has already been factored into markets and if the tariffs are quickly removed or top out at low levels then no worries and we move on to the next issue.

But it looks like we have further go on the trade war front with likely more tariff announcements on other countries and products ahead. Which means ongoing uncertainty for a while yet.

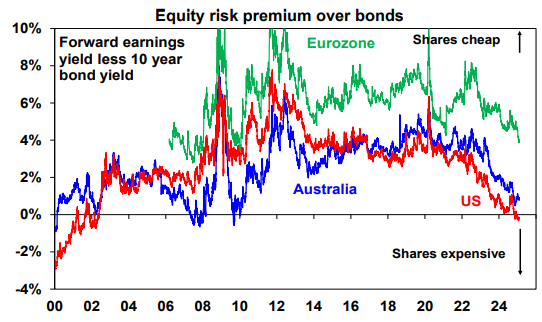

And with shares expensive – US shares offer no risk premium over bonds – we could be in for a volatile period, a bit like we saw in Trump’s 2018 trade war! Our view remains that a 15% or so correction is likely at some point this year. But trying to time this – down and up - will be hard.

Of course, some of this has already been factored into markets and if the tariffs are quickly removed or top out at low levels then no worries and we move on to the next issue.

But it looks like we have further go on the trade war front with likely more tariff announcements on other countries and products ahead. Which means ongoing uncertainty for a while yet.

And with shares expensive – US shares offer no risk premium over bonds – we could be in for a volatile period, a bit like we saw in Trump’s 2018 trade war! Our view remains that a 15% or so correction is likely at some point this year. But trying to time this – down and up - will be hard.

However, if we are right and share market falls along with political pressure from a tariff driven boost to the US cost of living act as a constraint on Trump causing him to limit his tariffs and pivot back to the more positive part of his policies (tax cuts and deregulation) then share market falls will be limited and we should still see positive returns this year. Albeit they will be more volatile and constrained than last year.

Implications for investors

While times like these can be stressful, for superannuation members and most investors, the best approach is to turn down the noise around economies and investing (and particularly Donald Trump!) and stick to an appropriate long term investment strategy to take advantage of the rising long-term trend in share markets given the difficulty in trying to time short-term swings.

3 topics