NAB launches first 5-year major bank senior bond issue since January 2020

NAB has launched the first benchmark 5-year major bank senior bond issue since January 2020 (ie, prior to the advent of the COVID-19 crisis). This was consistent with our expectations for an increase in Aussie bank senior bond issuance both prior to and post 30 June 2021 given the RBA's Term Funding Facility (TFF) has expired, which has been validated by a series of new AUD, USD, EUR, and GBP deals from ANZ, Bendigo, BoQ, Westpac, and Macquarie in the last few months. Since CBA has just reported its full-year results, we should see them come to market soon too.

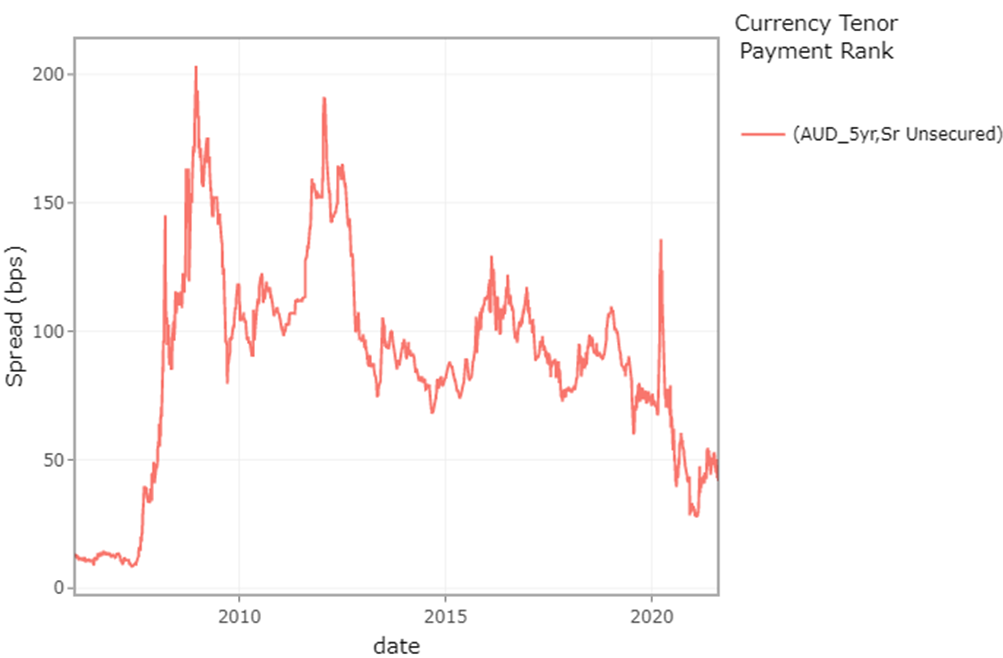

The new Aussie dollar, 5-year deal from NAB is likely to be extremely cheap funding for the bank given Coolabah's proprietary, constant-maturity 5-year major bank senior bond index is sitting in the low 40 basis point territory over the quarterly bank bill swap rate (BBSW), which is the tightest these spreads have been since 2007 (they did temporarily go a little lower about 6-8 months ago). The chart below is a screenshot from our systems that shows this index over time.

While Coolabah is forecasting strong bank senior bond supply over the next few years as they gradually repay the $188 billion borrowed under the TFF, the banks are benefiting from much higher levels of deposit funding than they had prior to the COVID-19 shock and the availability of extremely cheap wholesale funding in many different currencies, including AUD, USD, EUR, and GBP.

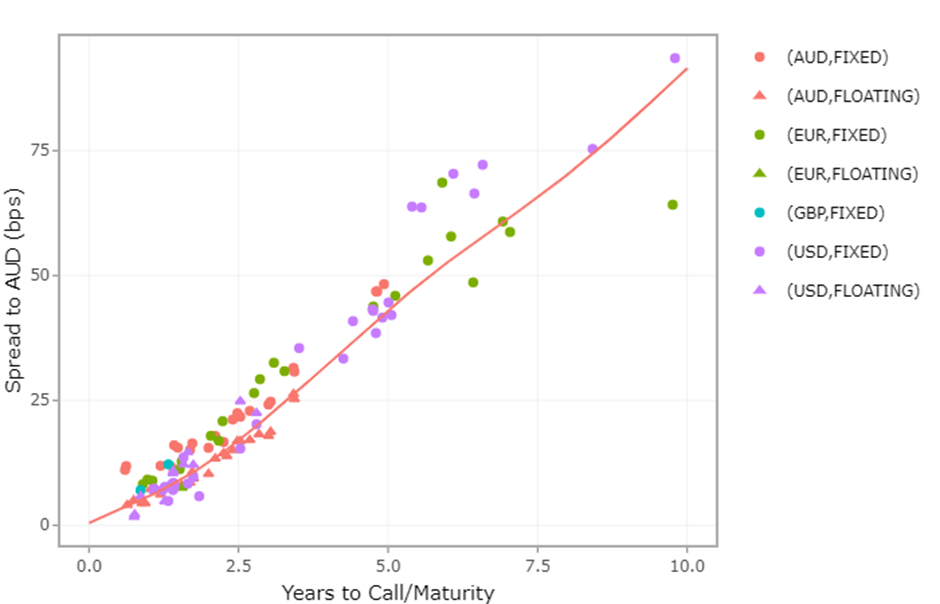

The screenshot below is from our systems showing where the major banks' senior bonds are trading right now in USD, EUR, GBP and AUD, hedged backed to AUD. You can see the USD (purple symbols) and EUR (green symbols) are below, or broadly in-line with, the AUD (pink symbols), implying that the cost of funding in USD and EUR is as cheap, if not cheaper, than in AUD.

One possible difference in AUD is the medium-term depth of demand relative to the massive USD and EUR markets. If the RBA and APRA continue to reduce the size of the banks' $139 billion Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF), which is an emergency liquidity portfolio, this will constrain the banks' ability to bid for one another's bonds using their CLF portfolios.

Historically, it has been quite common for the major banks to hold $10 billion or more of their peers' bonds within their CLF portfolios. The CLF was created because Australia's government bond market was so small, and was not big enough to provide sufficient High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) for the banks to meet APRA's Basel 3 liquidity requirements. So the RBA and APRA established the CLF as a back-up.

Yet with the government bond market now about $1.2 trillion in size, and the banks also holding over $300 billion of cash on deposit with the RBA, which is another form of HQLA, there is no longer any need for the CLF should APRA and the RBA choose to wind-it down to zero, as APRA has repeatedly stated it would do "in the foreseeable future".

Significantly, APRA is also asking the banks to build a new "contingent" form of liquidity, which looks like a back-up CLF 2.0, by the end of this year, which would provide them with self-securitised loans worth 30% of their Liquidity Coverage Ratios. In a crisis, they could give this collateral to the RBA, and borrow against it, which is exactly what they are able to do under the CLF (the difference being that they will not have to pay the RBA a standing fee for this contingent liquidity).

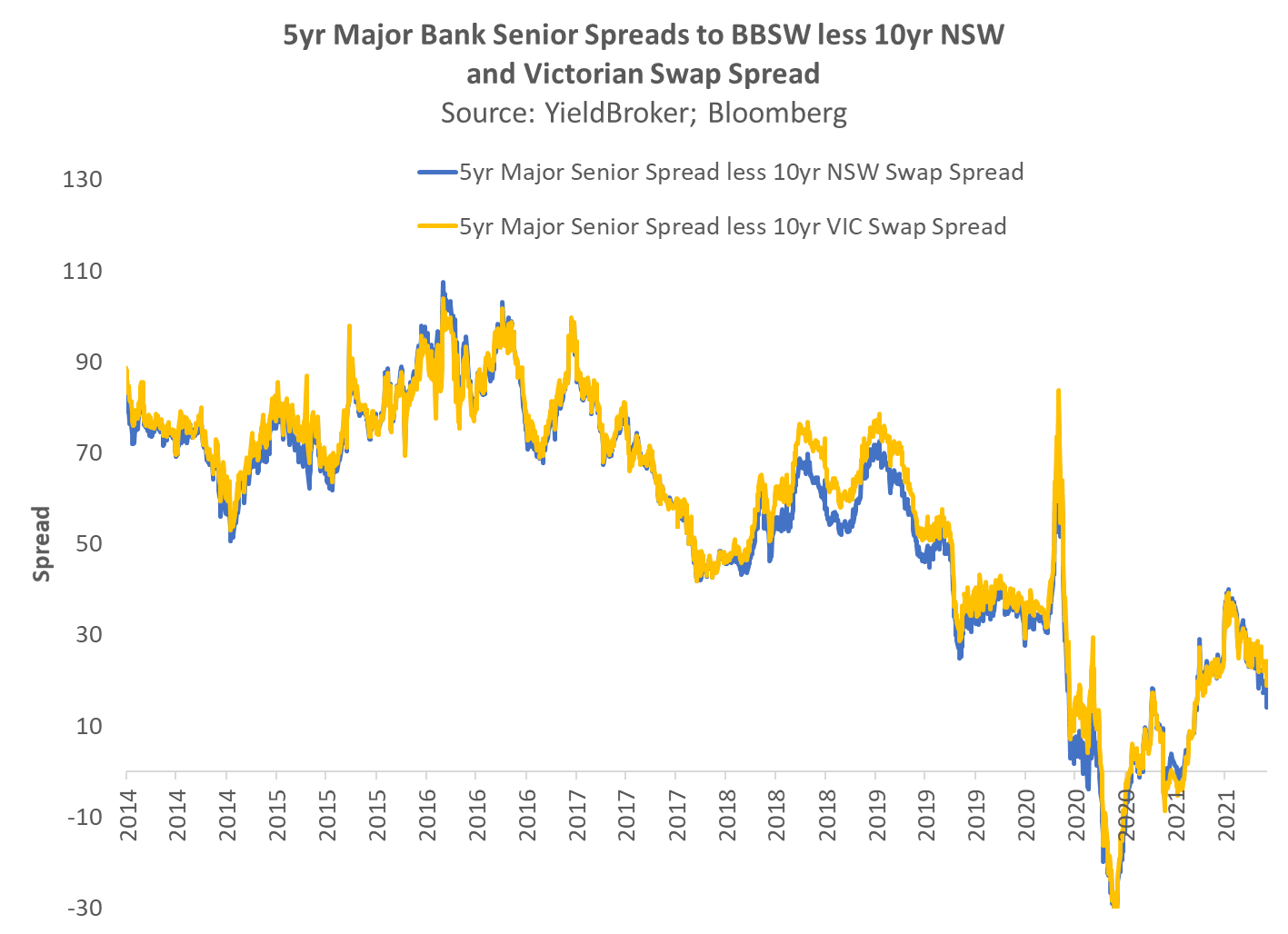

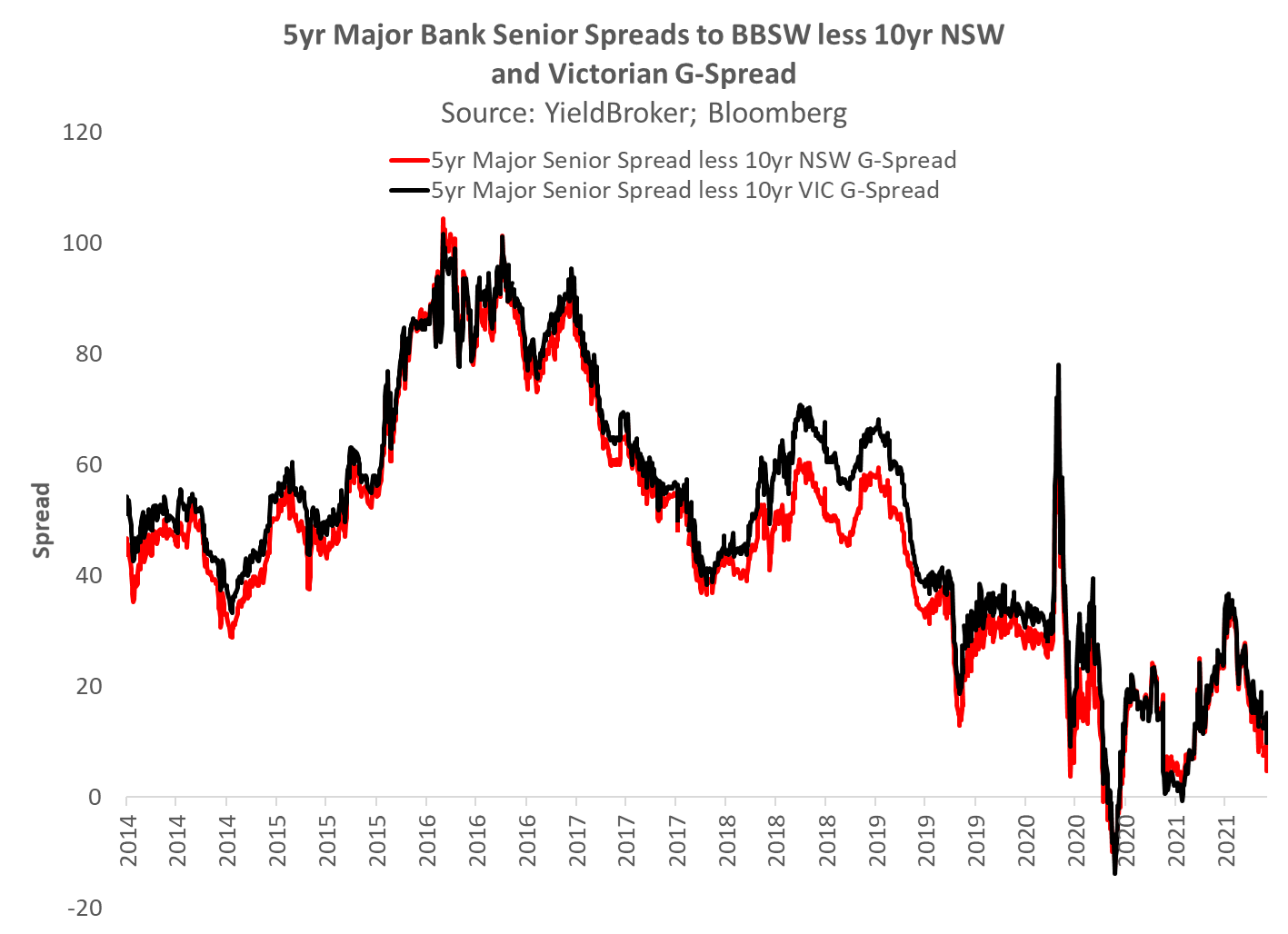

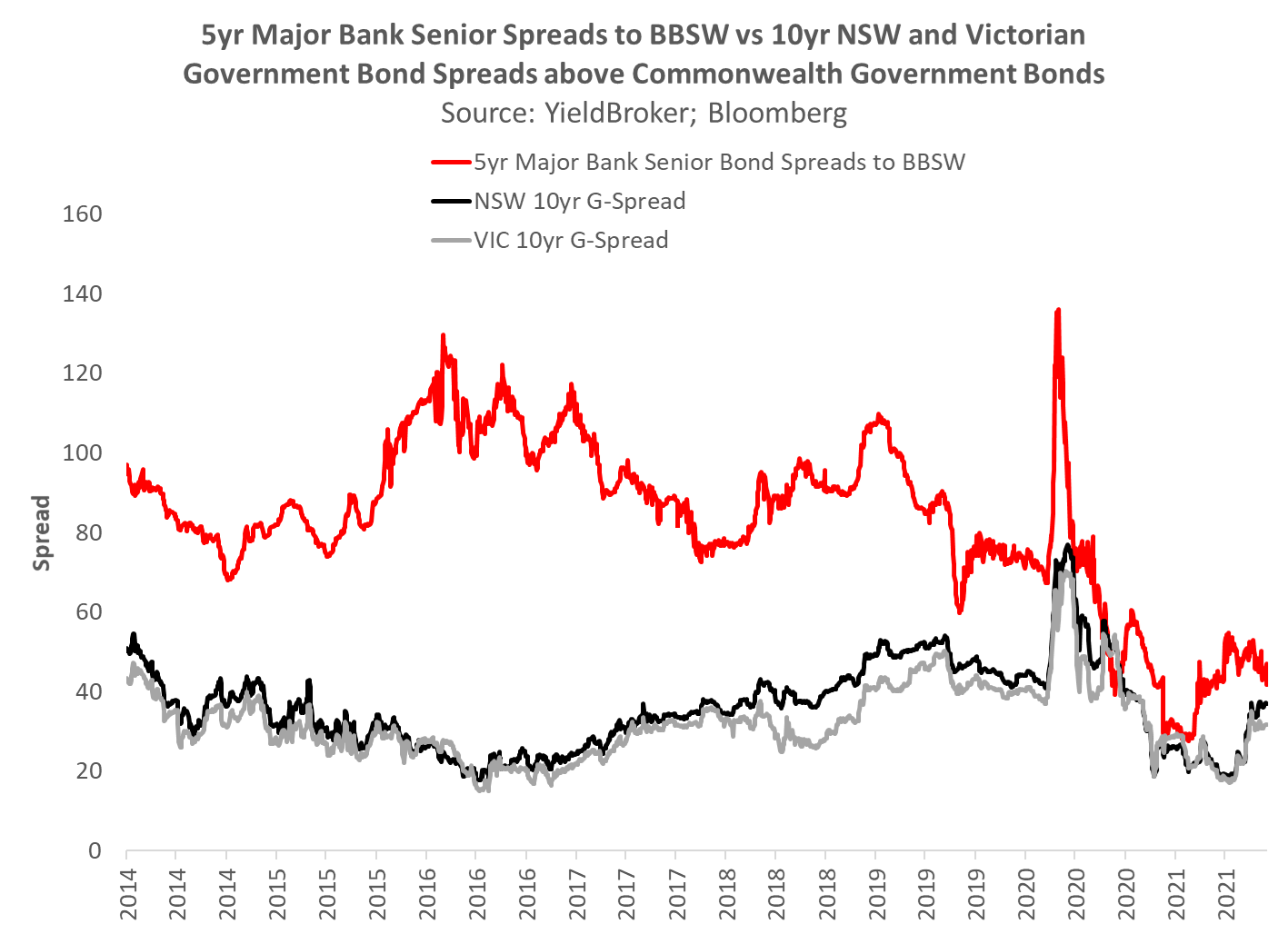

Here it is interesting to compare the spreads available to banks on HQLA relative to major bank senior bond spreads. In particular, we compare the spreads on NSW and Victorian government bonds expressed relative to the Commonwealth government bond curve (known as a g-spread) and the swap curve (called an asset-swap spread).

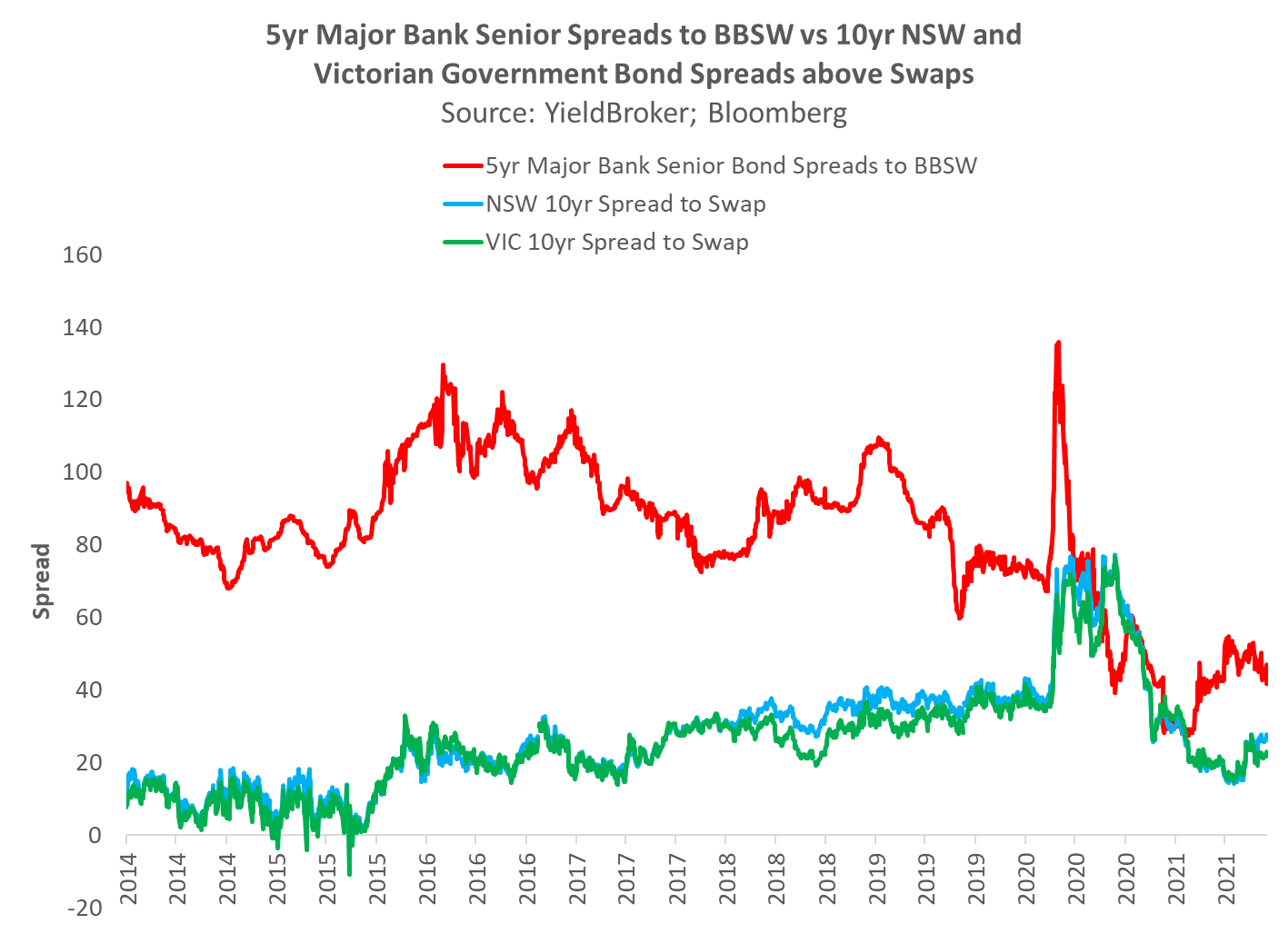

The charts below show that the spread differential between benchmark major bank senior bonds, which is the 5-year curve, and benchmark State government bonds, which is typically referenced as the 10-year curve, have rarely been smaller/skinnier.

One can also compare the outright spread levels, which is what we show in the next two charts. The very small spread differential is partly a reflection of the fact that the banks have $139bn in the CLF, and have been able to keep senior bank spreads tight by buying their own paper and RMBS issued by banks (and non-banks).

It also partly a supply story with little senior bank issuance over the last 12 months compared to the State governments, which have been issuing about $80bn to $90bn a year. Having said that, we are comparing government bonds to bank bonds, and the RBA is buying State government bonds to the tune of $1bn a week (it is obviously not buying much riskier bank paper).

But the data below suggests that either senior bond spreads need to move wider, or State government bond spreads should move tighter...

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

3 topics