Navigating the Cycle

In this month’s Insight, we showcase how we can use the changing business cycle as a signpost for asset class and investment style performance, a strategy known as regime based investing. Over the medium term, economic fundamentals are different across different stages of the business cycle and in turn asset class performance also varies. When the economy is booming, it is good to hold equities and other growth assets while value stocks should also outperform. Bond yields tend to rise in this environment, so you want less bond exposure. In a recession however this gets turned upside down. In this Insight, we dive deeper, and use our economic growth framework to determine the assets and styles best suited to each regime for multi-asset portfolios.

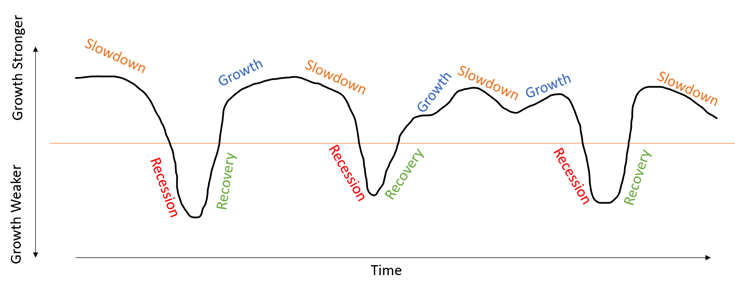

While regime-based investing is a relatively simple concept in theory, it can be quite complex in practice. First, we need to define the different stages of the economic cycle. We define four regimes as follows:

Growth: A growth regime is the most common state for an economy to be in. The explosive economic gains of the immediate post-recession period have passed, and the economy settles in for a lengthy period of “normal” activity. Normally in this regime, the unemployment rate is falling, inflation and wages growth are steadily rising, and consumers generally feel optimistic about the future.

Slowdown: A slowdown represents a period of below trend or slowing growth that isn’t severe enough to be classified a recession. Normally, this period would occur quite late in the economic cycle, perhaps after the unemployment rate has fallen to quite low levels and interest rates had been increased a reasonable amount. Often, this regime will precede a recession, though this is not always the case. Growth can naturally slow after a period in which it has been very strong. External factors, for example the Euro Crisis or US / China trade war could also cause a slowdown in growth without causing an outright recession.

Recession: A recession in our model is defined as a period where growth is below average and falling. Obvious examples include the period following the tech bubble and the Financial Crisis. However, we can also characterise less aggressive periods, such as the Asian Financial Crisis or 2015 hard landing fears in China as recessionary periods.

Recovery: The recovery is normally the period following the recession where the impact of fiscal stimulus and easier monetary policy lead to a period of very strong economic growth. This robust growth tends to not last very long, with the economy rarely in the recovery regime for very long before moving into a growth phase.

Below, we show a stylised example of this cycle. Generally, the economy will cycle between growth, slowdown, recession and recovery. However, this is by no means certain. Often the economy will see mid-cycle slowdowns or a shift straight from growth to recession. Recovery is also not guaranteed, as evidenced by the 1990s experience in Japan.

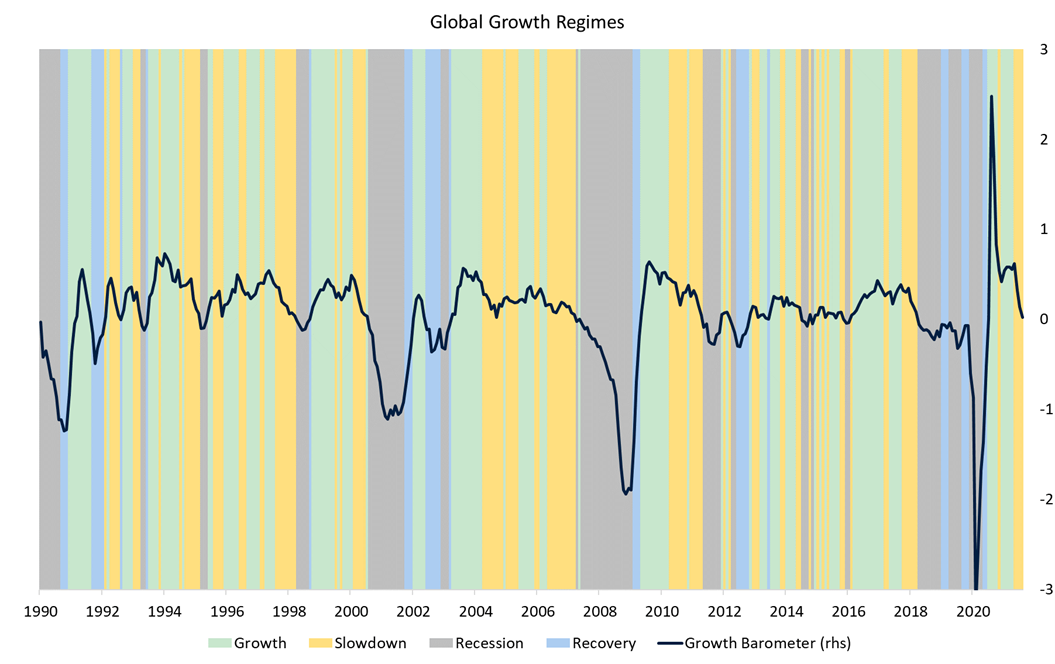

We can create an unbiased estimate of historical regimes quantitatively using our global growth barometer(1). We construct the four regimes based on whether the barometer is showing above or below trend growth and whether the barometer is rising or falling.

The figure below shows the output of this analysis. There are several observations we can draw from this figure. The global cycle isn’t as simple as the stylised example above. The recovery stage of the cycle tends to be quite short. Most of the time, the economy is in the growth phase of the cycle, followed by the slowdown phase. The post Financial Crisis phase has tended to feature lots of short, sharp switches between regimes. The growth cycle in the decades preceding it was slower moving, but more volatile.

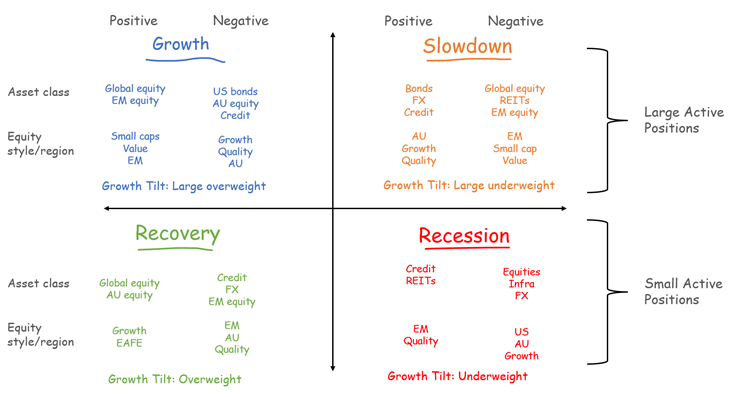

The next question is: what to do with this information? If we know what cycle we are in, how should we position a portfolio? To make this decision, we enlist the help of our portfolio optimiser – a tool we lean on heavily as part of our Strategic Asset Allocation Review process. To generate the inputs, we bucket returns, volatility and correlations between asset classes and within equity styles by regime. Then, within each regime and allowing for some exposure constraints, we allow our optimiser to produce two fully invested portfolios: maximum return and maximum Sharpe ratio(2).

Below, we show the largest active positions (relative to the average exposure across all regimes) across asset classes and within equity styles and regions for each regime(3).

There are a number of observations we can make from the optimisations:

- Positioning is most active in the growth and slowdown regimes, the tilts in the recession and recovery regimes are much smaller.

- In a growth regime, the portfolio holds little defensive asset exposure. Growth exposure is predominately gained via global equities, and the weight to Australian equities is the lowest across any of the regimes. Within equity styles, small caps and value is favoured over growth and quality.

- Moving into the slowdown regime, overall growth exposure is reduced significantly and large allocations to bonds and credit are built. Within equities, EM equities are removed and exposure to global equities is reduced substantially. FX exposure is increased, and REITs are replaced with infrastructure. Value and small cap exposure is reduced in favour of growth and quality styles.

- In the recession regime, growth asset exposure actually increases relative to the slowdown regime. Bonds and FX exposure is reduced. This surprising result likely reflects the forward-looking nature of markets and the predominance of short and sharp recession phases in the 2010s. Infrastructure exposure is swapped back with REITs and EM equities are added back into the portfolio. Within equity styles, quality is favoured over growth and EM equities are favoured over US equities (perhaps reflecting the dominance of the US in the global economic cycle).

- In the recovery regime, growth exposure is increased a little further, though credit exposure is reduced. Within growth assets, exposure to both REITs and infrastructure is reduced in favour of Australian and global equities. Growth and DM ex US equities are favoured within the equities portfolio.

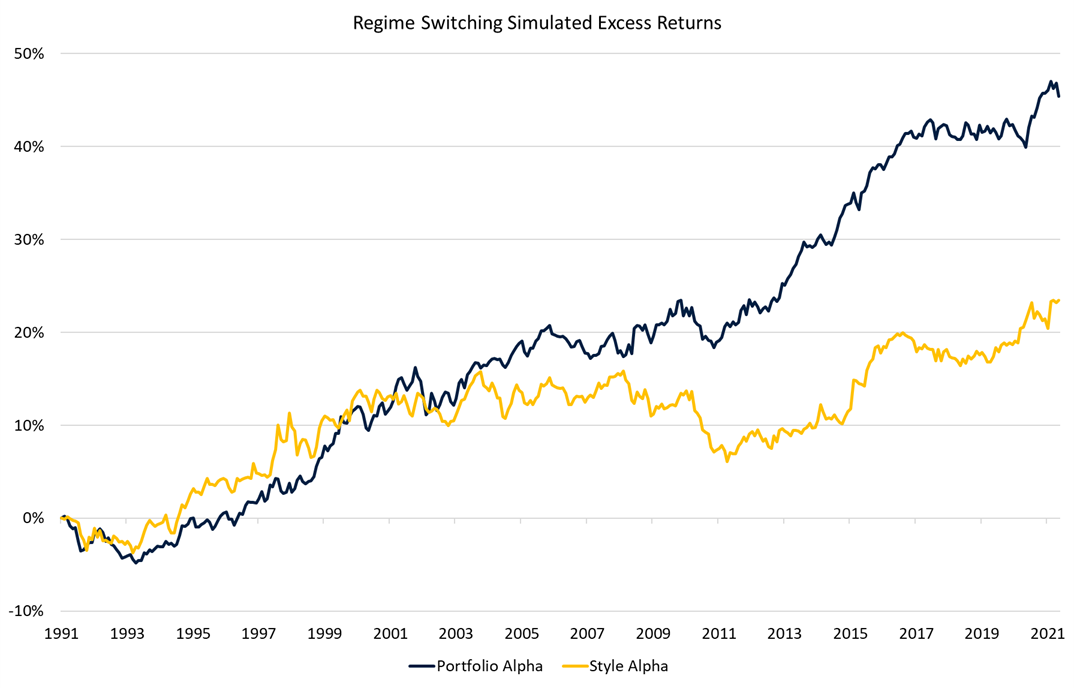

While most of the above seems intuitive, testing the allocation strategies historically gives more confidence around whether or not they would be a good idea to implement. Below, we show the excess portfolio performance of both the multi-asset and style portfolios relative to exposure neutral benchmarks(4). Both portfolios imply outperformance versus a static strategy through time. Interestingly, the performance of the multi-asset portfolio is much more stable than the style portfolio. We think this may reflect higher volatility across the individual style returns and higher correlations between them.

So, what are the portfolio implications of the analysis? The results help affirm some of our existing investment beliefs and generate some new ideas.

- There seems to be a strong correlation between asset class and equity style performance and economic regime, which can be used to some advantage in a tactical process.

- In a period when economic growth is slowing, we want to reduce growth asset exposure and within equities reduce exposure to managers who have more exposure to cyclical regions or styles (emerging markets, value etc).

- While we may not necessarily want substantial exposure to Australian equities across most regimes (as suggested by the style portfolio allocation), from a multi-asset perspective a home bias makes sense, as it sits well amongst other asset classes, particularly in non-growth regimes.

- Despite having a reasonable correlation with equity risk, credit as a defensive asset is attractive even in slowing growth environments.

- Foreign currency exposure is an important diversifier across all regimes, and the value of tactically moving it based on different regimes isn’t as high as other asset classes.

- Every equity style and regional tilt warrants a meaningful allocation across at least one of the regimes except developed market equities ex USA. This is more than likely driven by the exceptional underperformance of this market over the past three decades and raises questions about whether it can continue or whether US equities are due for a meaningful period of underperformance.

Currently, the portfolios are slightly overweight growth exposure, though equity exposure is below the SAA. We are also underweight bonds in favour of credit and have a tilt towards quality (relative to our neutral positioning) within the equity portfolio. We also have no direct emerging market equity exposure. Within the equity portfolio this aligns reasonably closely with the slowdown regime. Our multi-asset positioning doesn’t clearly align to any particular regime. In large part this reflects the fact that there a multitude of considerations which inform our decision making and it would be odd for our portfolio to completely align with any one of them alone.

That said, the growth barometer is currently reading slowdown, and this suggests caution, particularly with respect to our overall equity exposure. As always, we will continue to monitor the economy and markets closely and make changes to the portfolio where appropriate.

(1) (VIEW LINK)

2 topics