“Necessary but not sufficient”: Hurdles to overcome in equity manager selection

In a 2017 research paper, Martijn Cremers argues that three pillars underpin success as an equity manager: skill, conviction and opportunity. But what metrics can investors use to determine which managers actually have those attributes?

Ranking funds purely on their three-year track record is a noisy signal because managers have growth versus value style biases. There are managers whose style just happens to be in favour in one period and whose performance subsequently reverts to the mean. Some advisors in the fund selection game recommend lowering tracking error to mitigate risk, but low tracking error makes it almost impossible to beat a benchmark after fees.

Past research has found an inverse relationship between fees and performance. But if low fees are the objective then there is no point in considering active management at all. Fee minimisation makes sense for an investor who is just looking for exposure to market risk – avoiding the difficult task of manager selection – and does not care about taxes.

However, investors indifferent to taxes are a rare breed. In Australia, franked dividends and the capital gains tax discount for long holding periods mean that holding an index fund is tax-inefficient for most investors. In particular, the franked credits are too low for investors with low tax rates. So investors necessarily face the question of whether to deviate from the index.

There are three metrics investors can use in their fund search to narrow the field to the subset of managers worth considering in detail: Track record versus a risk-adjusted benchmark, active share and fees. Importantly, all three metrics need to be considered jointly. What follows is a snapshot of the evidence on these metrics. These metrics can be used for evaluating the two main investment vehicles for self-managed superannuation funds and high-net-worth investors: fund managers and advisors to investors with separately managed accounts.

Past performance and active share in separately managed accounts

In a 2022 paper,[i] researchers examined approximately 4,000 separately managed accounts holding U.S. equities over 13 years from 2007 to 2019. A typical account holds 80 stocks and has an active share of 80 per cent (for example, if a portfolio held 80 stocks and its benchmark was the S&P 500 there are 420 stocks not in the portfolio, so the active bets are about 80 per cent).

The researchers computed after-fee alpha, defined as the return in excess of each account’s exposure to indices that can be replicated with index funds (for example, the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000). The researchers considered the relationship between track record, active share and after-fee alpha. Track record was measured as after-fee alpha over the prior two years. Active share is the proportion of stock holdings which do not overlap with holdings in the portfolio’s benchmark.

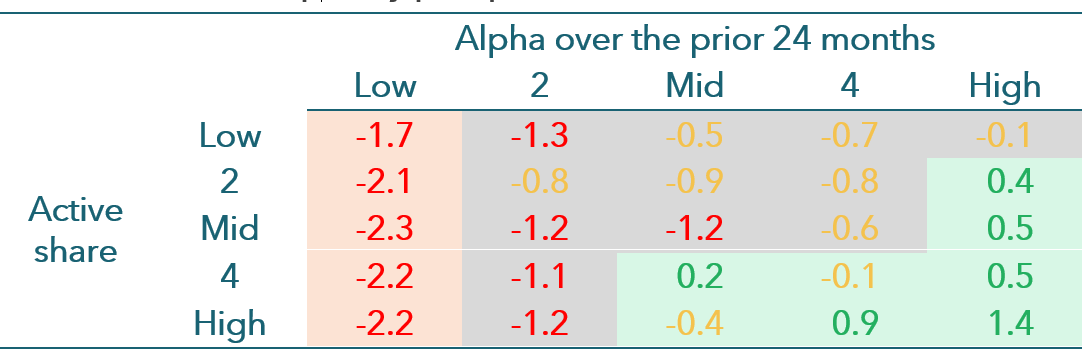

The researchers showed that after-fee alpha was increasing with track record and active share (Table 1, lower right). Each cell represents about 4 per cent of accounts (about 150). A strong track record alone does not guarantee success. The best performing funds with low active share still underperform in a subsequent period because their bets don’t deviate enough from benchmark to offset their fees. And active share alone just represents conviction. The highest active share accounts with track record in the bottom 60 per cent still underperform next year. Necessary conditions for future performance are track record and enough active bets.

Fees and active share in mutual funds

Cremers (2017) measured the performance of approximately 3,000 U.S. equity mutual funds over 26 years from 1990 to 2015. As above, the performance metric is after-fee alpha versus a benchmark which can be replicated with exposure to index funds. Average expense ratios ranged from 0.7 per cent in the lowest fee quintile to 1.8 per cent in the highest fee quintile. The median active share is 56 per cent in the lowest active share quintile and 97 per cent in the highest active share quintile.

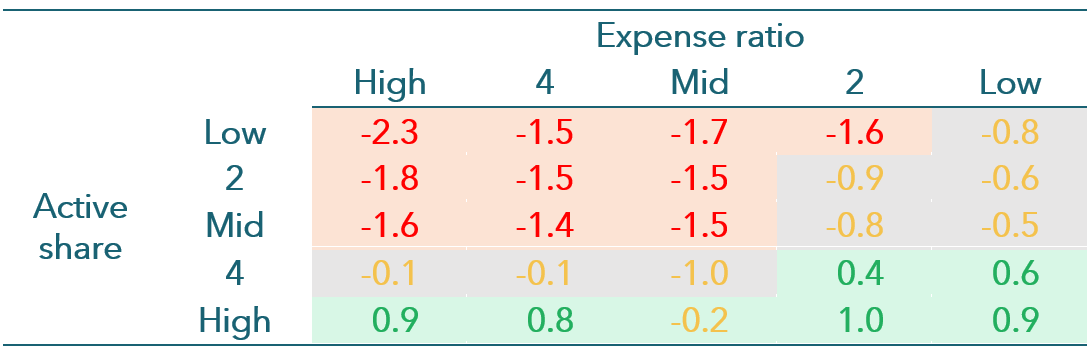

The researchers showed that after-fee alpha is eroded by fees and increases with active share (Table 2, lower right). On average each cell represents about 120 funds, although there is an increased concentration of funds with high fees and high active share, and low fees and low active share. Low fees alone do not guarantee success. In the low fee quintile, outperformance is concentrated in the top 40 per cent of funds by active share. A high active share on average is associated with higher performance, but an active share does not need to be in the top quintile, provided fees are low enough.

Conclusion

Selecting investment managers is hard because track records are short managers have growth or value strategies that are persistent, and whether growth beats value over short horizons is difficult to predict. But a starting point for manager selection is to consider three metrics: risk-adjusted performance, active share and fees.

Focusing on any one of these metrics in isolation will likely lead to future underperformance. Low-fee index funds are tax inefficient, performance is often mean-reverting because of persistent management styles and active share alone just measures the size of active bets.

A high-performing manager is likely to have modest fees, a track record of positive risk-adjusted returns and takes enough active bets to offset fees.

References

Cremers, M., 2017. Active share and the three pillars of active management: Skill, conviction, and opportunity, Financial Analysts Journal, 73, 61–79.

Cremers, K.J., J. Fulkerson and T. Riley, 2022. Active share and the predictability of the performance of separate accounts, Financial Analysts Journal, 78, 39–57.

5 topics