No such thing as a free lunch

Through the pandemic, global fiscal support packages have gone a long way towards helping to offset the decline in corporate and household income. In the U.S., where signs of activity bouncing back from the disruption of lockdown had initially raised a question mark over the need to extend the CARES Act when it expires, the resurgence in virus infection rates has prompted over 40% of the country to reverse or pause its reopening. This may be an uncomfortable moment for the U.S. Congress. They clearly need to continue providing fiscal support, but they cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that, long after COVID-19 is contained and defeated, the U.S. taxpayer will still be living with the consequences of this spending blitz. Already, the fiscal deficit is expected to hit 18% of GDP and federal debt is set to exceed 100% of GDP this fiscal year.

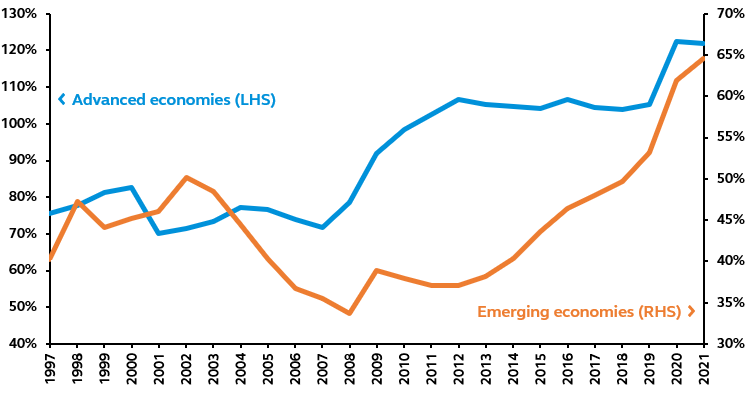

Advanced vs. emerging economies gross gov’t debt

Gross gov’t debt as percent of GDP, 1997 – present

Source: IMF, Principal Global Investors. Data as of March 31, 2020.

The U.S. government does not stand alone with its fiscal problems. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), public debt across advanced economies could reach 122% of GDP, matching levels last seen in WWII. The run-up in public debt in emerging markets is smaller but, at 63% of GDP, will reach its highest level in history.

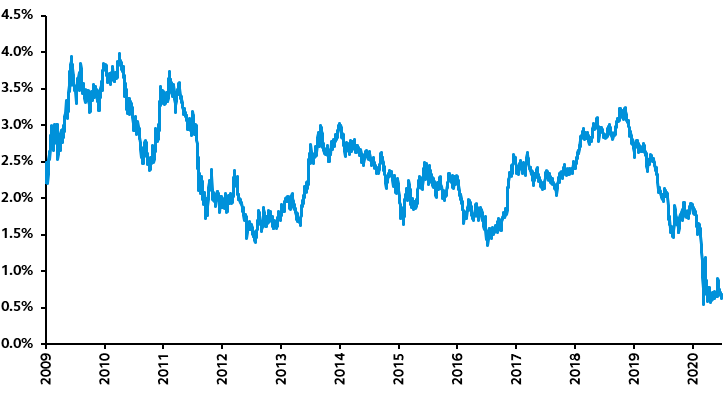

In fairness, for many advanced economies, these numbers perhaps sound scarier than they really are. Much of the stimulus announced is of a temporary or even one-off nature, so it will be relatively easy to return deficits to more normal levels once the crisis is over. In addition, while governments may be borrowing more than they did during the Great Financial Crisis, the cost of financing debt has dropped. Today, the U.S. government can borrow for ten years at an interest rate of just 0.65%, almost 300 basis points lower than a decade ago – fiscal stimulus has almost never been cheaper.

10-year U.S. Treasury yields

Percent, Jan 2009 – present

Source: Bloomberg, Principal Global Investors. Data as of July 1, 2020

Fiscal-monetary coordination – a snazzy term for monetary financing?

Unlike other nations, the U.S. government does not need to worry too much about who will finance the debt surge. As the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. is afforded a privileged position. When the economic & market backdrop deteriorates, foreign demand for the U.S. Dollar and U.S. Treasuries tends to increase. This has permitted the U.S. to maintain current account and debt imbalances that, quite frankly, would have likely resulted in severe crises in other countries.

More pertinently perhaps, by purchasing sovereign debt in enormous quantities in order to support the economy, the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) quantitative easing program has also provided a helping hand with funding the government deficit, avoiding a run-up in market tensions.

This “fiscal-monetary coordination” has been impressively effective. With economic slack holding down inflationary pressures, the Fed can easily continue to purchase sovereign debt without being accused of dismantling its credible inflation fighting reputation. This also means the U.S. government can comfortably extend pandemic fiscal rescue plans without inciting a sharp rise in market tensions and interest rates.

Yet praise for fiscal-monetary coordination during tough times can rapidly morph into accusations of monetary financing if policymakers fail to reverse emergency measures once the economy has fully recovered. The U.S. Congress will need to determine ways to reduce the deficit once the crisis has passed otherwise it will risk the Fed’s credibility and, in turn, could potentially lead to a rise in bond yields and the end of the 40-year bull market in bonds.

Pick your poison: taxation or growth

In the upcoming U.S. Presidential election, taxation will inevitably be a hot topic. Increasing the U.S. corporate tax rate from 21% to 28% would clearly raise revenues. However, not only would it be unpopular with many voters, but the dent in the budget deficit would arguably be almost inconsequential compared to the negative impact on business investment and job creation. Higher corporate taxes would not be a complimentary tool to U.S. plans to entice companies away from China and encourage onshoring. After the GFC, many advanced economies tightened their belts and reduced their debt ratios meaningfully via public spending cuts and taxation – but the unappetising side effect has been years of meagre growth.

Governments may instead prefer to grow their way out of debt. If they can ensure nominal growth rates are above market interest rates, the debt-to-GDP ratio will fall, but – and here’s the catch – they need to avoid triggering inflation.

This was the favoured strategy for many countries after WWII. Via a program of strong growth and low interest rates, the U.S. managed to shrink its public debt from a peak of 122% of GDP to an impressively low 26%. Yet, in order to achieve this, the US also had to live with high inflation and pursued active policy preventing interest rates from rising. In other words, monetary financing. The modern era of independent, inflation-targeting central banks was essentially created to prevent policymakers from succumbing to these public debt financing pressures.

Eventually, policymakers will need to decide

The U.S., and other countries around the world, have a difficult task ahead of them. Faced with this daunting reality, no wonder governments are increasingly reluctant to extend fiscal support programs.

Nonetheless, while we remain in the throes of the pandemic, the premature withdrawal of emergency support due to worries about future debt-related burdens would be self-defeating. Over the next 12-18 months, bond yields are likely to stay at low levels, while equities and other risk assets should be supported by expansionary monetary and fiscal policy – a potential Goldilocks moment for investors.

Yet once the crisis is behind us, and normal economic behaviour has resumed, investors may demand a reversal of these emergency policy measures. Governments, central banks and the public may want policy rates to remain lower for longer, but market pressures may think differently. Which one will be the adult in the room?