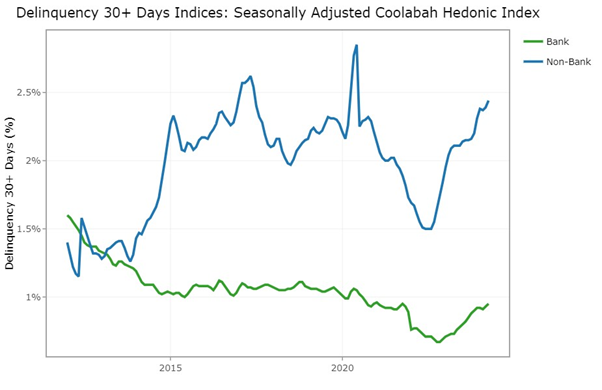

Non-bank defaults continue to spike

Arrears on non-bank home loans continue to climb towards historically very elevated levels, which is consistent with Coolabah's long-held central case. In the first chart below, we take all securitised non-bank home loans and compare their 30 day arrears rate with securitised bank-issued loans. There is a striking difference in the default experience of loans in the regulated bank vs unregulated non-bank sectors. These data are also seasonally-adjusted using the X13 methodology and compositionally-corrected for new RMBS issuance (which artificially suppresses arrears rates as new RMBS bonds are always default-free) via a hedonic regression technique that Coolabah pioneered back in 2018. Observe how the arrears rate on non-bank loans (blue line) is exploding towards recent record highs. At the same time, bank-issued loan arrears (green line) are very benign.

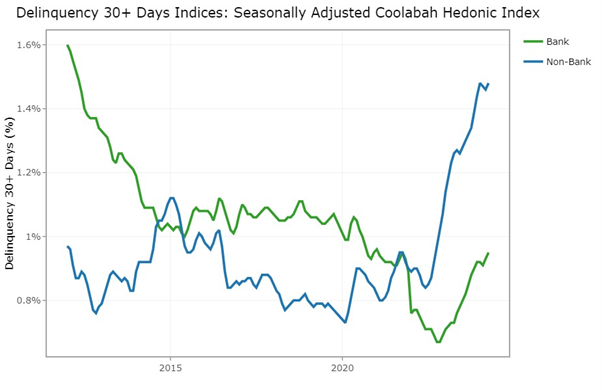

Some investors claim it is unfair to compare non-bank loan arrears with bank-issued loan performance because non-bank lenders are primarily focused on extending finance to sub-prime, or very risky, borrowers. These folks like to compare only the best "prime" non-bank loans with "prime" bank loans, which are meant to be of the same quality. In the second chart we do precisely this, removing all sub-prime or non-prime loans issued by non-banks. The results are fascinating.

During the good times, prime non-bank loan arrears are similar to bank arrears. But during the bad times as interest rates soar, non-bank prime borrowers reveal themselves to be much, much riskier than bank customers. They are, in fact, still sub-prime loans compared to prime bank loans...

The key take-away is that while bank balance-sheets are fine, and extremely well-capitalised, non-banks are enduring some serious pain, which will only intensify if the RBA does not cut interest rates. Put another way, you are going to find much more default risk amongst unregulated non-bank lenders relative to APRA-supervised banks that are characteristically far more conservative.

In the ashes of the Bonza airlines collapse, the AFR's Karen Maley wrote this week about the explosive growth in non-bank lending since the 2008 GFC as banks were compelled to shift the riskiest borrowers off their balance-sheets. It is worthwhile reflecting on these insights:

One of the explanations for the exponential growth of private credit is that the banks are hampered by strict capital regulations, which means it’s harder for them to lend...

This suggests that many of the loans that private credit firms are writing are loans that the banks have chosen not to pursue, rather than loans that they can’t make.

Financial regulators have been extremely slow to recognise the risks posed by the explosive growth in private credit. They’ve tended to take the attitude that investors who tip money into private credit funds are capable of taking care of themselves, and that borrowers fully understand the risks...

But that’s a backward-looking approach. As private credit grows, regulators need to look closely at the systemic risks that arise as more and more of the financial system becomes reliant on capital that isn’t permanent...

As JPMorgan boss Jamie Dimon last month warned in his annual shareholder letter, fast-growing new financial products “often become an area of unexpected risk”.

“Frequently, the weaknesses of new products, in this case private credit loans, may only be seen and exposed in bad markets, which private credit loans have not yet faced.”

4 topics