Patient Powell plays it safe

Markets have been rather listless these last few months, contrasting with the beginning of calendar 2021, when financial markets moved directionally based on key narratives such as the “Blue Wave," “reflation” or the “delta variant”.

Even now, as August draws to a close, things are better, sure - but they're still not great nor are they back to normal.

COVID-19 infections are still affecting economic performance, labour markets and consumer and business confidence. At the same time, government and central bank policy remains hyper-accommodative and at emergency levels.

This begs the question: do we require the emergency level any longer and will central banks begin to normalise policy?

Jackson Hole

Each year the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (USA) hosts a conference with central bankers, policymakers, academics, and influential economists in attendance.

Globally, financial markets go into high alert prior to the event for the chance that one of the presenters – usually the US Federal Reserve Chair – may present new guidance or policy initiatives – which may ultimately be implemented and profoundly affect financial markets and economies.

However, it should be remembered that Jackson Hole is not a Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. This means no policy initiatives can be discussed and voted on during the gathering.

Now, markets are looking for any communication of future initiatives.

Much ado about nothing?

Jackson Hole’s reputation is owed greatly to past Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s speeches given between 2007-2012.

In 2007 to 2009, Bernanke provided guidance surrounding the financial crisis at the time, while in 2010-2012, he provided forward guidance to the new rounds of quantitative easing (QE), dubbed QE2 (2010), Operation Twist (2011) and QE3 (2012).

However, in the last decade the Symposium has largely been a non-event, where markets were in a goldilocks environment of not so hot, not so cold growth and inflation, where central bankers provided monetary accommodation and weren’t in any immediate rush to tighten policy.

It should be noted that in 2019 the significant move in the S&P500 was due to the trade tariffs announced on the Friday that Jackson Hole started, rather than Jackson Hole itself, where the market had already priced in 100% chance of a 25bp rate cut for the September FOMC meeting.

Source: State Street Global Markets

2021 Jackson Hole

This year’s Jackson Hole was titled “Macroeconomic Policy in an Uneven Economy”, held virtually on 27-August.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was the keynote speaker, where he spoke positively, telling attendees (and the world) that “substantial further progress” has been made towards the Fed’s two goals of maximising employment and stable prices (inflation), allowing them to start tapering off some of their economic support, referring to their asset purchase program.

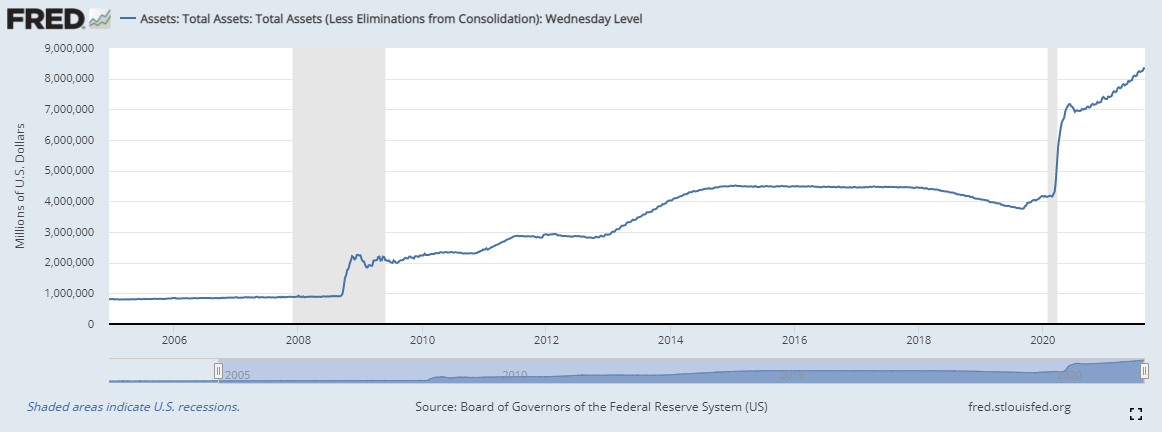

It’s important to remember at this juncture that the Fed currently maintains the target Fed Funds Rate at 0 to 0.25% p.a. and has in place an asset purchase program purchasing $120 billion USD of bonds per monthly, split $80bln US Treasuries and $40bln US agency MBS.

To highlight this visually, that’s the spike in the Fed’s balance sheet from ~4.2 trillion USD in February 2021 to ~7 trillion USD in May 2020, and then a continuous 120 billion per month since.

To quote myself from an article published on 9 August about the prospect of the RBA tapering their QE (emphasis added):

“What we’re talking about is not a hard stop to these purchases, nor is the potential tapering an unknown event that might spook markets like it did in 2013 – no, it’s a well forecast likelihood from central banks, where asset purchase programs will be slowly reduced to lower amounts and may not even be completely stopped at all.

Also, if these central banks start to fall short of their inflation and unemployment target, I’m sure they’ll be quick to add to their bond purchases, to provide cash (liquidity) to the market.

Hence, we’re not talking about a withdrawal of monetary accommodation or a reduction in liquidity, we’re talking about them adding less accommodation each month, but still an addition.

I’m most fond of using the act of driving a car as my metaphor: where central banks will be accelerating less, and certainly aren’t even close to pumping the brakes.”

What Powell is speaking about is not directly related to the cash rate, first they’re looking at tapering their QE program first, before (likely) pausing, then if conditions are correct, they may hike the Fed Funds Rate (cash rate) thereafter >> and hope there’s no recession between now and then!

A million reasons not to tighten

In our outlook at Mason Stevens, we weren’t expecting anything profoundly shocking to come out of the Jackson Hole symposium this year, where the Fed – like other central banks – has been slowly providing forward guidance to avoid another calamitous “Taper Tantrum” type of event such as we experienced in 2013.

In fact, all the recent speeches by FOMC voting members as well as other notable Federal Reserve officials has been that they’ll likely taper QE over 6-12 months, likely starting some point at the end of CY2021 (we think in January 2022), where they taper by 10 or 20 billion per month, therefore over 6-12 months.

However, all this estimation must be grounded in reality that the FOMC has a million reasons not to tighten, and only 1 reason to tighten – inflation.

In the “not to tighten” camp, we’ve got lower labour force participation, COVID-19 infection rates, Powell’s term as Chair ending in January 2022, “transitory” inflation, trade-war with China, corporate solvency to name but a few.

We’d focus on three key ordinances as to why Powell and the Fed are likely in no hurry to taper or tighten.

Not to tighten: U-6 Unemployment

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has several gauges of unemployment, termed U-1 to U-6.

U-3 unemployment is the methodology we’re used to seeing published, and most similar to what is used in Australia by the ABS; however, we find it is not the best for measuring the affect of the pandemic at present.

The reason?

U-3 measures a semi-restricted unemployment rate by total people looking for work, where millions of Americans were not looking for work during the pandemic. Hence not working and not looking for work and not part of the labour force, where U3 was low.

U-6, however, is a broader measure of labour force participation including all persons marginally attached to the labour force.

U-6 currently shows us that the US unemployment rate is 9.2%, not 5.4 (U-3 method).

The Federal Reserve knows this distinction shows a vast amount of labour force slack is present, where their labour market is not tight and is similar to mid-2016 conditions, when inflation was not running hot.

[Sidebar: the FOMC showed no rush to taper its QE and hike rates in 2016]

This knowledge helps inform them that the current inflationary spike is likely transitory, where the market is not tight enough to see higher wage expectations.

Not to Tighten: COVID-19

The US currently has ~200k COVID cases per day, with more than 100k hospitalisations.

While they have been efficient at manufacturing vaccines and a large portion of their civilian population double-dose vaccinated, the rising hospitalisations are putting strain on the medical system and potentially require “flattening of the curve” travel restrictions put back in place, where state economies will likely slowdown either way due to the uncertainty.

Not to Tighten: Reconfiguring the Fed

Powell’s term as chairman is up in early 2022, which has led to speculation about whether the Biden Administration – particularly Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen – will seek to reconfigure the Fed’s Board, and where Powell will be reappointed.

On top of Powell’s term ending, two other Trump appointees – Vice President for Supervision Randal Quarles and Richard Clarida’s terms both end in 2022, where there’s also another vacancy on the Board due to Trump nominees Stephen Moore and Judy Shelton not gaining Democrat Senator support to be appointed.

All-in-all, this gives Biden the unique opportunity to reshape the Board to align more with his administration’s priorities.

Some priorities being the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan, which involve a large amount of fiscal deficit spending and bond issuance, which will require high levels of monetary accommodation.

Patient Powell

In aggregate, we are now calling him “Patient Powell”, where Powell has refrained from suggesting a tapering announcement would be coming soon or relatively soon, instead focusing on tapering “this year”, and markets projecting an announcement to come in any of the September, November, or December FOMC meetings.

Patient Powell is also de-linking the end of the Fed’s QE taper with an imminent lift off in their cash rate, where “the timing and pace of the coming reduction in asset purchases will not be intended to carry a direct signal regarding the time of interest rate liftoff, for which we have articulated a different and substantially more stringent test.”

As mentioned above, less acceleration but not braking (yet).

We believe Patient Powell is playing a subtle game of softly-softly forward guidance, preparing markets for the upcoming taper to form positive sentiment. At the same time, he's waiting for inflation to be shown to be transitory, which will inform whether to remove the rest of the emergency monetary accommodation, once the emergency has passed.

And if he’s successful, he’ll likely retain his job come March next year.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire. Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

Expertise