Rates are finally rising – here come the bond market doomsayers

FIIG Securities

For the first time in over a decade, it looks like overnight cash rates are finally going to rise at some stage in 2022.

This is the moment the bond doomsayers have been waiting for – a chance finally to put the boot into an asset class that has, in truth, performed spectacularly over the last 40 years given its low risk compared to other asset classes and products.

Facts and a balanced view have commonly been missing in the commentary of forecasters who are employed to make predictions that solely assist their employers to sell their products – mainly equity-driven – and as such, have typically been uniformly wrong in their views surrounding 10-year yields for the last 20 years:

Now I am clearly not saying that 10-year yields will not rise from here or that they haven’t risen at various points – the above chart shows we have had long periods when they have risen.

We started talking about the overnight cash rate, which has been held at a record low of 0.1% for almost two years as part of the RBA’s pandemic response.

I highlight the 10-year rate because that is typically the benchmark market rate used as the risk-free rate in many asset pricing models (more on this later).

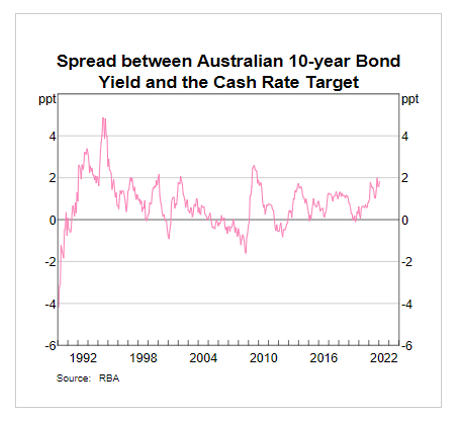

The spread between the two has remained relatively range bound depending on the prevailing economic circumstances over the last 30 years or so:

We are approaching the top of that range now, which lends credence to the view that at the start of hiking cycles, the 10-year rate typically is a good guide as to where the terminal cash rate will head.

Market forecasters seem to be around this consensus, although as we have seen, they haven’t been the most reliable source. I prefer to look at actual pricing, which is showing us the likely outcome as it has in the past.

So rates are trading in a relatively stable and hopefully (as far as markets ever allow) predictable range.

Next, we come to performance – if the rates themselves have traded relatively predictably, what about performance?

The 10-year rate has indeed risen approximately 40bps in 2022, which for the 10-year government bond price would have delivered a return of approximately -3.6%, offset by income of approximately 0.25%.

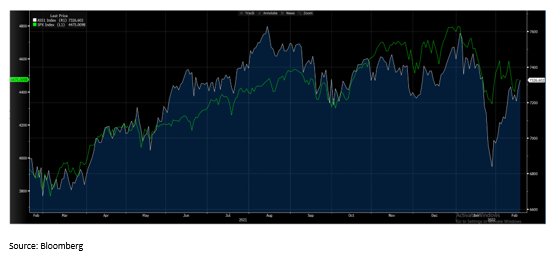

In the same time period (31st Dec to 16th Feb) the ASX200 has returned -2.15%, although this masks the volatility experienced, having gone from a high of 7,474.4 on the 13th of January to a low of 6,838.3 on the 27th of January – a loss of 8.51% - before recovering to its current level.

Now these performance figures don’t paint a particularly appealing picture, but that is of course just on the face of it.

The government bond that showed a mark to market performance of -3.6% does not have to be sold for its capital to be returned to the owner – they must simply wait for maturity.

In the equity market price is all – because that is the only way you get your capital back, and so the price at the moment is the only price that matters. The converse is true with a government bond, where your credit risk is deemed to be zero, and regardless of the market, the government will return your money on the maturity date.

If anyone seriously doubts this, please let me know. I would be happy to introduce them to the millions of government employees and pensioners who have absolute reliance on our government meeting its obligations as and when they fall due.

It is this safety that will ensure there are always buyers of government debt – those that have an absolute preservation of capital mandate and/or asset/liability matching requirements, such as life insurance companies.

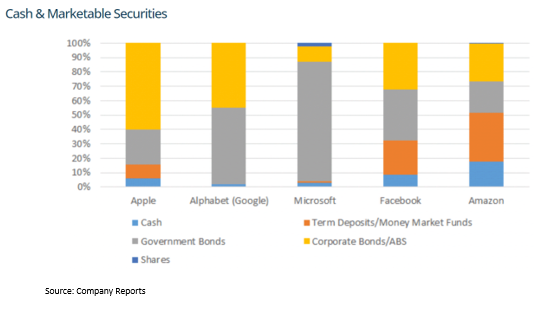

Indeed, as we have pointed out before (see here for the article), the world’s largest companies run significant government and corporate bond portfolios to improve returns on cash.

This in total is hundreds of billions of dollars invested in bonds for their capital stability (i.e. return of capital at maturity), and returns superior to those available in cash.

Note the heavy allocation to corporate bonds. Issued by companies rather than governments, these bonds pay more than the government due to their associated credit risk.

However, at least in the Australian experience, this credit risk is extremely low. Investment Grade rated companies in Australia have defaulted on their obligations only three times in the last 30 years or so, and yet can offer up to three times the return of a similar tenor government bond.

What is more surprising to me is that Australian investors continue to chase marginal income improvements in exceedingly risky and volatile investments (mainly equities) rather than accept a slightly lower return in exchange for a negligible risk to their capital.

Income

Boy oh boy, do Australians love their franking credits. And no wonder if the taxman, through his very generous largesse, writes a cheque each year, increasing your income by 30% on top of your already generous tax-free superannuation income stream.

Tax structuring, in my opinion, can reasonably be placed at the centre of portfolio construction outcomes for the vast majority of Australians.

Franking on dividends, capital gains exemptions of principal residences (100%) and any capital asset owned for more than a year (50%) and negative gearing (although to be fair this applies to any asset bought with borrowed money, not just property – it is just that property is easier to spruik) have combined to make the average Australian investor more exposed to risk than almost any other investor across the world.

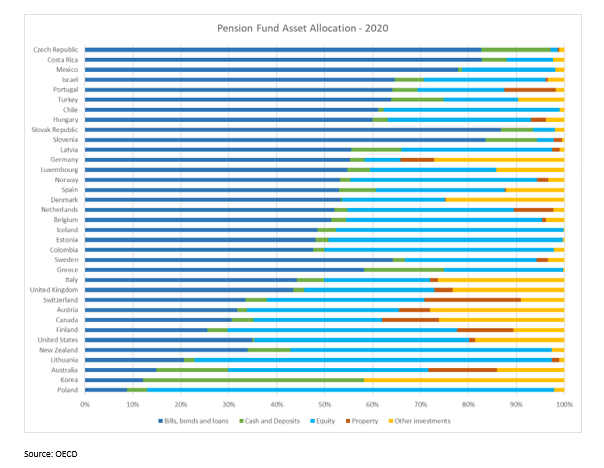

The below chart will be familiar to long term WIRE readers or attendees at our seminars:

It shows Australian pension funds have the third-lowest allocation to bonds and the fourth highest allocation to equities + property in the OECD.

In short, Australian pensioners have the highest exposure to risk of any developed nation on earth, in those funds that they can least afford to lose.

Leverage

There has also been commentary that there is a huge amount of leverage in the debt markets, which when yields rise, and prices fall, makes bond markets subject to reflexivity, or in more simple terms, a vicious circle of selling.

Indeed, there was a time back in late 2018 when the US Federal Reserve first started raising rates, and the share market had its latest “Taper Tantrum” (the original was in 2013), linked by some market commentators to an unwinding of leverage in risk parity funds.

These funds seek to take advantage of the traditional non-correlation of equity and bond returns by being long both (as they in theory balance out when one or the other falls or rises) but matching the risk (typically expressed as volatility). As we showed earlier, equity volatility is significantly higher than bond volatility, and so these funds lever up the bond side to match the risk – hence the name ‘risk parity’.

As in any investing situation, leverage amplifies performance, both good and bad, and in this case as equity prices were also falling, the leverage on the bond side made these funds forced sellers.

Fortunately, the US Treasury market is the largest and deepest market in the world, and these flows were easily absorbed. We have not seen the same necessarily in the equity world, where liquidity is supposed to be superior, and yet leverage also plays its hand here too. The recent collapse of highly concentrated and levered fund Archegos Capital is a case in point, leading to billions of losses for its prime brokers when they couldn’t sell the huge share positions their loans were secured against.

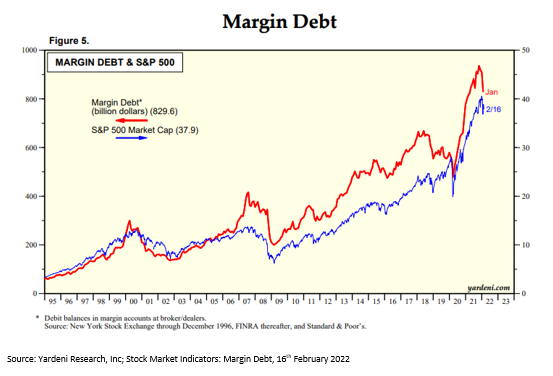

Indeed, in the US at the moment, it would seem that margin debt has actually fuelled a lot of the post-COVID rally, as this chart from Yardeni Research shows clearly:

The Australian experience is similar, although it can clearly be seen the aggressive expansion since the 2008/9 GFC has not happened again domestically compared to the US experience, although the level of margin debt in the equity market is at its highest level since 2010:

However, the ASX200 and S&P500 are very closely correlated, as the below chart shows – so any unwinding of the US margin debt into a falling market is likely to have a similar effect on our own market, and given the level of debt there and the composition of their index being made up of many more unprofitable tech companies, for example, the ensuing equity volatility is likely to be severe, and probably orders of magnitude higher than any equivalent bond market volatility.

Conclusion

As bond yields have risen, the protecting ‘shock absorber’ effect of high-quality bonds becomes more relevant than ever, as the further the yield can fall, the further the price can rise in the event of a risk-off market event.

No doubt whilst yields were lower than where we are now – the Australian 10 year government yield is at 2.23% as I write and reached its all-time low of around 0.60% in March 2020 – government bonds were less attractive as there was a smaller potential price rise on offer if a market shock occurred. However, these current levels represent a much better starting point with which to buffer investors’ portfolios against equity shocks.

With significant geopolitical risk on the immediate horizon in Ukraine and potentially Taiwan, plus central banks lifting overnight rates into slowing growth economies (demonstrated by the significant flattening of the government yield curve, which once inverted has predicted every recession since WW2), we would argue that the place for bonds in portfolios is becoming more compelling rather than seeing a case for abandoning them as we hear in other parts of the media.

Allied to yields well north of 4% for solid investment grade credit with reasonable tenors, this should be an opportunity for investors to grab hold of a secure, reliable income stream from very capital stable instruments rather than doubling down on discretionary dividends from risky, volatile equities for a tax benefit at the top of a hugely stimulated global economy which is having its punch bowl withdrawn, and at a likely rapid pace.

4 topics

Jon is FIIG Securities’ Chief Investment Strategist. Also a Chartered Accountant, Jon has been working in multi-asset class investment markets for over 15 years, and now specialises in providing fixed income solutions for FIIG’s clients.

Jon is FIIG Securities’ Chief Investment Strategist. Also a Chartered Accountant, Jon has been working in multi-asset class investment markets for over 15 years, and now specialises in providing fixed income solutions for FIIG’s clients.