RBA drops a neutron bomb on the Aussie housing market and makes a heinous mistake in its monetary policy statement

Sadly, the RBA is a little unhinged right now. It is mindlessly repeating mistakes it made both before and after the pandemic, the essence of which is predicating truly extreme policy positions on rubbery forecasts of the future that are not worth the paper they are written on.

You can get a sense of just how discombobulated the RBA is by a heinous error in the statement released by governor Phil Lowe following the board meeting this week when the RBA imposed a second back-to-back 50 basis point rate increase on borrowers. In the crucial final paragraph of this statement, the RBA made this claim, which is grossly incorrect:

Today's increase in interest rates is a further step in the withdrawal of the extraordinary monetary support that was put in place to help insure the Australian economy against the worst possible effects of the pandemic.

The RBA's rate hike on Tuesday did not, in fact, represent it withdrawing extraordinary monetary support. In October 2019, almost six months before the pandemic shocked markets, the RBA had cut its cash rate from 1.0% to 0.75%. Last month, the RBA lifted its cash rate from 0.35% to 0.85%.

Accordingly, the RBA's cash rate prior to its board meeting on Tuesday was actually higher--and hence policy was explicitly more restrictive---than it was on 3 March 2020, one day before the RBA (foolishly) decided to reduce its 0.75% cash rate by only 25 basis points to 0.50%. The RBA was promptly forced to remedy this mistake with an unprecedented intra-month meeting 16 days later on 20 March 2020 when it cut the cash rate by another 25 basis points to 0.25% and announced a suite of additional monetary policy support measures.

The bottom line is that the RBA's pandemic-related stimulus as represented by its target cash rate had been fully removed last month. It is not clear what prompted the RBA to suggest otherwise in July.

Spidey sense is tingling

I honestly don't like writing this, but my spidey sense is tingling pretty loudly right now in respect of the RBA's sudden swing from relentlessly telling Australians that rates will not rise until 2024 at the earliest to imposing one of the sharpest hiking cycles in the world on borrowers in the form of a staggering 125 basis points of rate increases in the very short space of two months (or over three meetings on the 4 May, 8 June and 6 July).

The RBA is further conditioning households via the media to expect a third back-to-back 50 basis point hike in August, which would mean they will have had to wear a stunning 175 basis points of rate increases in just three months. It would also approximate the 175 basis points of hikes the RBA imposed in August and October 1994 with the difference being that households in 2022 are much, much more interest rate sensitive than they were 28 years ago...

One of the most worrying features of the RBA's commitment to aggressive rate hikes is that they will likely snuff-out whatever hope the central bank had of helping Australians realise decent wage growth. For years the RBA has been criticised for allowing the unemployment rate to remain excessively high, and for not supporting stronger 3-4% per annum wage growth that would be consistent with it sustaining core inflation around the middle of its target 2-3% per annum band.

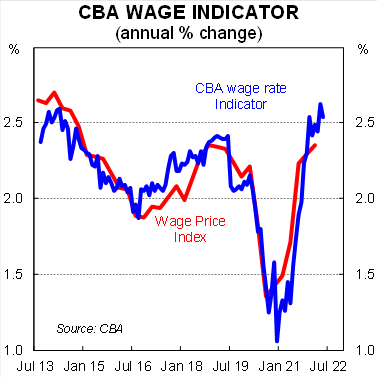

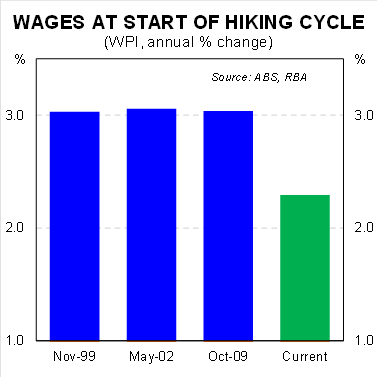

CBA economist Gareth Aird kindly provided the two updated charts below that show CBA's proprietary wage indicator benchmarked against Australia's official wage price index. This is based on a matched sample of circa 300,000 CBA customers. CBA's wage price indicator tracks the wage price index almost perfectly. And it demonstrates that there is no evidence that wages growth is running hot, as the RBA has alleged when rationalising the need for tighter policy. In fact, on CBA's numbers, wages growth is expanding at a circa 2.5% to 3.0% pace, which is below the level the RBA was hoping to observe to meet its inflation objectives. The second chart shows that current Australian wages growth is also materially below the levels evidenced prior to the RBA's previous hiking cycles.

Aird says that "despite the tightness in the labour market, actual wage outcomes are their lowest on record for a tightening cycle and yet we have the most aggressive cycle for decades combined with deeply negative real or inflation-adjusted wage growth".

I felt similarly disconnected from the RBA's view of the world in late February 2020 when I was privately trying to warn them that the pandemic would precipitate a cataclysmic shuttering of global financial markets. The RBA initially dismissed these concerns, arguing in late February and early March 2020 that there was no need for active policy interventions. This was reflected in the RBA's decision to only cut rates by 25 basis points at its first meeting in March 2020, and its rejection at the time of the need for a more comprehensive package of measures, including some form of quantitative easing (QE). As noted above, it only took a couple more weeks before the RBA did a 180 degree turn at is intra-month meeting on 20 March 2020.

We also found fault with the RBA's extreme negativity after March 2020, which failed to account for the impact of the unprecedented fiscal and monetary policy stimulus. Whereas the RBA projected a huge increase in unemployment, we argued that it would promptly settle at a modestly higher rate around 6%, which it did. Along similar lines, our modelling implied that house prices would rise by up to 20% following a minor 0-5% correction between March and September 2020, which the RBA rejected on the basis of its view that house prices could not climb materially in the absence of population growth (this was a line that Governor Lowe repeatedly trotted out). When the RBA cut rates again in November 2020, and belatedly launched a full-scale QE program, we upgraded our forecasts for capital gains of 20-30%, which is what was ultimately realised.

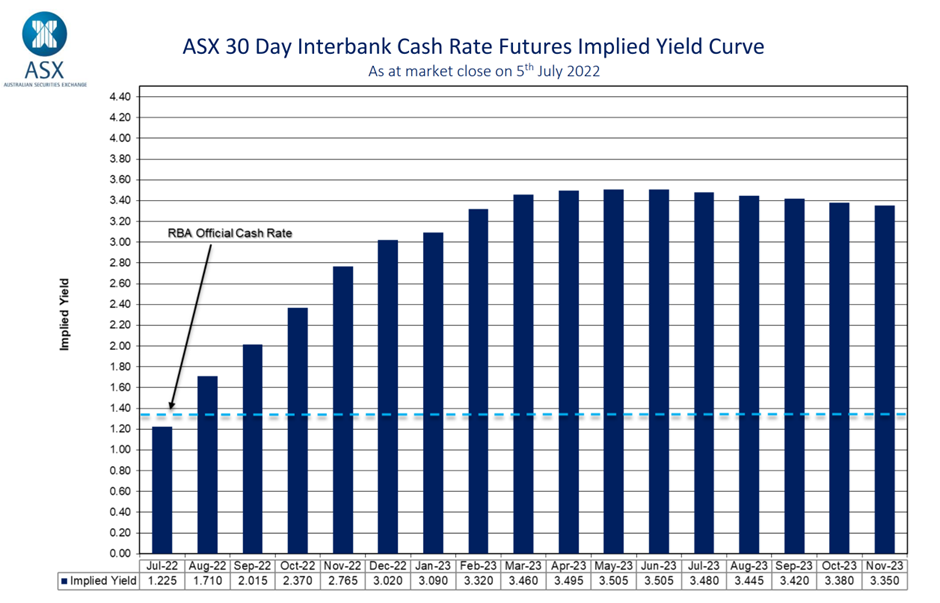

Household expectations shock

The RBA appears to be comforted that it can raise rates more aggressively than it has at any time in the past 25 years because markets are pricing in an even bolder hiking profile. Markets expect the RBA to lift its target cash rate to over 3% by December 2022 with a peak north of 3.5% in 2023.

Yet nobody seems to seriously believe market pricing for the cash rate, which is attributable to one-sided illiquidity in interest rate derivatives that has been evident since the RBA--by its own admission--deeply damaged its policy credibility by suddenly dropping its 2024 interest rate peg in November last year. This is probably the single most embarrassing event for a central bank since George Soros pushed the British currency out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in the early 1990s.

The consensus view is that once the RBA restores the credibility of its policy framework, market liquidity in interest rate derivatives, and objective pricing for the path of the RBA’s future cash rate, will adjust back to more normal levels.

The problem is that Aussie households have not been expecting a 2.5% cash rate, let alone the 3.5% the market has priced. Households were repeatedly advised by the RBA not to expect rate hikes until 2024, which was backed by their formal interest rate peg whereby they bought the 2024 Commonwealth bond to keep its yield at just 0.1%.

Aussie consumers and businesses were further actively encouraged by Governor Lowe to load up on debt and spend as much as possible because the RBA would keep their cost of capital low for long. As recently as late last year, the RBA roundly dismissed the idea that it could even consider raising rates in 2022.

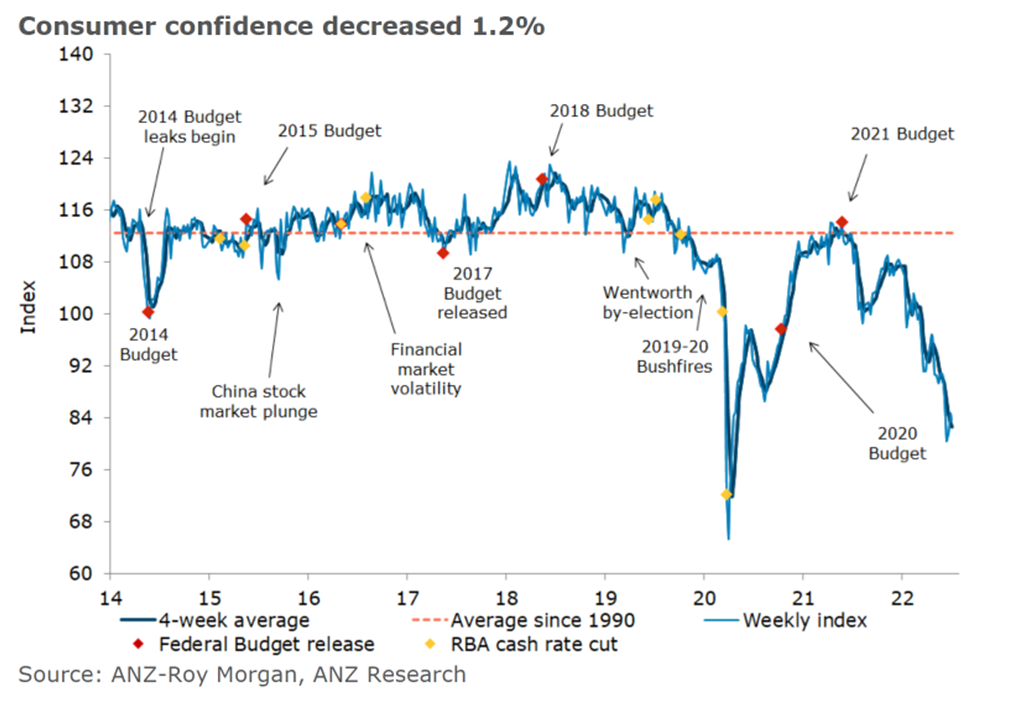

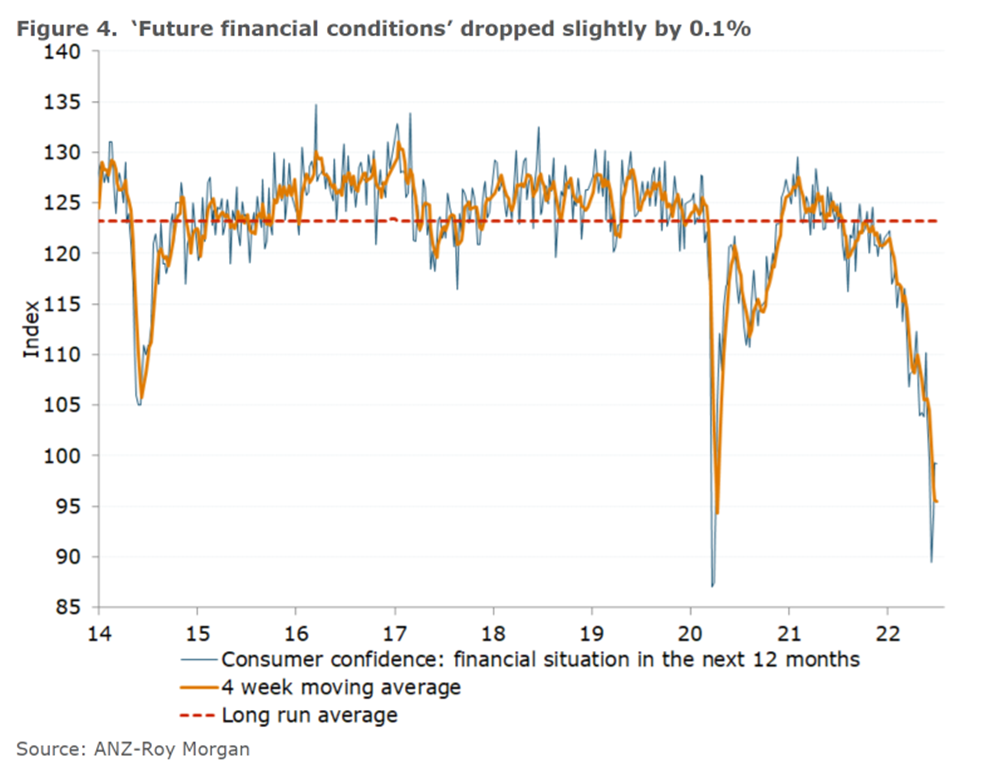

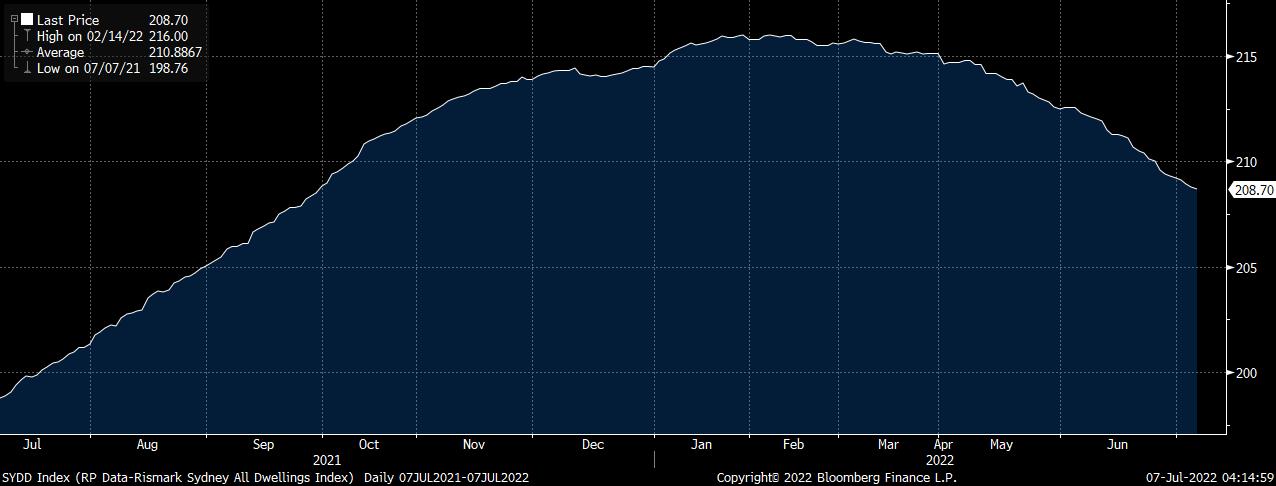

One can observe the real-time reaction of Aussie households to this radical change in outlook in the high-frequency consumer confidence surveys and the daily house price index data reported by CoreLogic.

Consumer confidence in Australia has plunged to crisis levels around its GFC and March 2020 marks. House prices are likewise quickly cratering, especially in the two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne, which tend to cyclically lead the rest of the country.

It is one thing to tell households that you got it wrong, and rates are going to have to increase in 2022, not 2024. But it is quite another thing to suddenly lift rates by 125 basis points in just two months (or over three meetings), and signal that another 50 basis point hike in August is likely---with more to come thereafter. This is now the sharpest RBA hiking cycle since its experiment with super-sized hikes in 1994 when households were far less interest rate sensitive than they are today. As CBA's Gareth Aird notes, a third 50 basis point hike in August would be a “more aggressive pace than almost any other central bank”.

I get the need for, and support, higher interest rates. But I would be much more careful in my use of what could easily turn into a financial weapon of mass destruction, bankrupting scores of households and businesses. A more prudent path would be to raise rates by 25 basis points at each meeting, and nowcast by collecting data on the consequences of these policy changes given the limits to forecasting in the current environment.

Caution is especially appropriate in light of the fact that the key drivers of Aussie inflation, including oil prices, food prices, and building costs, have all been materially elevated by one-off supply-side impacts that will inevitably fade with time. In contrast to the US, Australia does not have a burgeoning wage/price spiral. The RBA also meets much more regularly than its US counterpart, which theoretically affords more policy flexibility.

Household income and assets shocks

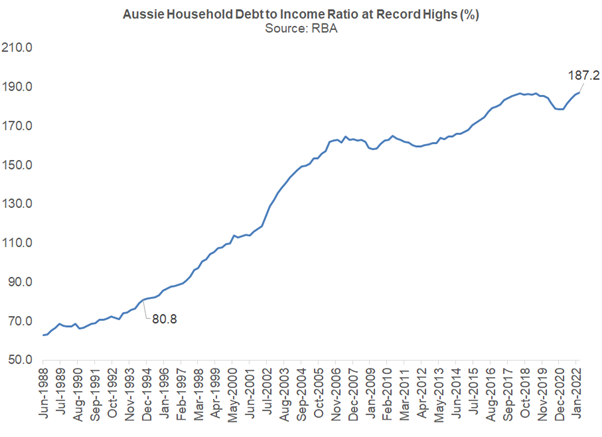

The last time the RBA experimented with super-sized hikes in 1994 the Aussie household debt-to-income ratio was just 82%. Today it sits at a record 187%. Consumers have never been more sensitive to interest rate changes. And they have never been more unprepared for rate hikes given the RBA's propaganda campaign over 2020 and 2021 that was designed to convince Australians that hikes would not materialise for years to come.

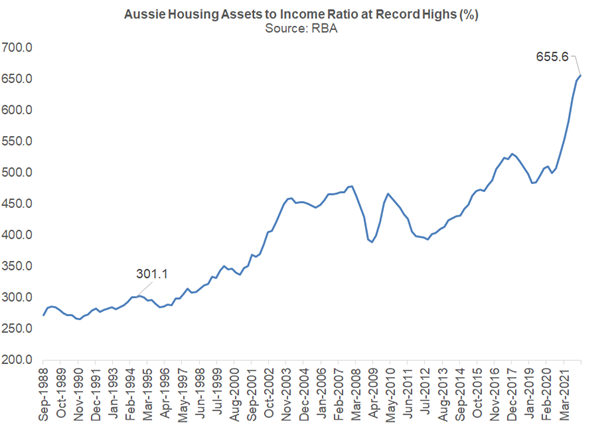

As we have explained before, we expect the RBA's hikes to trigger a 15-25% decline in national dwelling values, which would be the largest destruction of household wealth in modern times. The RBA's own housing model points to a bigger, 30-40% decline, which would reverse-out all of the post-pandemic capital gains. Here it is important to remember that housing was arguably the key monetary policy transmission mechanism that drove a lot of Australia's perceived prosperity in 2020 and 2021. The RBA's pre-emptive hikes, motivated by unreliable forecasts of the future, could therefore sacrifice crucial employment and wage gains that Australia has only recently obtained.

Back in 1994, Aussie housing assets were worth 301% of household disposable income. Today that figure has jumped to 656%. And housing as a share of total household financial assets is sitting near record highs despite the growth in both superannuation contributions and the value of our super assets.

In summary, Aussie consumers are going to be hammered by an unusually large conjunction of headwinds, including:

- The fastest interest rate increases in a quarter of a century, which will crush disposable incomes;

- A massive, albeit hopefully temporary, reduction in real wage growth as a result of a huge, one-off increase in inflation attributable to a conga-line of supply-side shocks;

- A record decline in the value of their largest asset; and

- The largest decline in the value of their superannuation savings since the GFC.

One mitigant could be fiscal policy, although it is not clear whether this will add or subtract from growth over the next year or two.

The most interest rate sensitive economy in the world

Australia not only has among the highest household debt-to-income ratios in the world. It also has among the highest proportion of borrowers with fully variable-rate debt that prices directly off the RBA's cash rate. This is precisely why monetary policy in Australia is so potent: it has out-sized effects on household behaviour because it immediately impacts almost all deposit and loan rates.

Historically, about 85% of all Australian mortgages were variable-rate, moving up and down with RBA cash rate moves. In countries like the US, UK and New Zealand, most loans are fixed-rate. This means borrowers are much more insulated from the impact of central bank hikes: they only adjust to higher rates once their fixed-rate loan matures.

During the pandemic, the RBA lent banks $188 billion of 3-year fixed-rate money at a cost of between 0.1% and 0.25% per annum, which they passed on to borrowers in the form of cheap fixed-rate loans. This drove the proportion of fixed-rate loans across the mortgage market up from 15% to circa 40%. Yet these were short-term, fixed-rate products and most will shift back to a variable-rate in 2022 and 2023.

According to CBA, some $500 billion of Aussie fixed-rate mortgages roll into variable-rate loans in the next couple of years. And these loans are all on 2.25% to 2.50% fixed interest rates. Borrowers could therefore see their monthly interest repayments almost double when these loans roll-off into variable-rate format.

Expect an abrupt change in policy once the consequences are clearer

There is a real prospect that the RBA may have to stop hiking, and possibly start cutting rates again, if it over-eggs the required monetary policy tightening. Indeed, financial markets are starting to price in RBA rate cuts next year (see chart below). And the RBA is clearly getting more nervous about the spectre of crisis-level consumer confidence combined with record declines in house prices, superannuation and real wages all conspiring to smash consumption, which is one of the most important drivers of demand. The AFR's Karen Maley writes that the RBA may proceed with greater caution at future meetings, and is focussed on changes in household behaviour, which is something that Governor Lowe also appropriately stressed in a recent speech. Specifically, Maley comments:

Although there’s a universal expectation that the Reserve Bank board will plump for another rate rise at its August meeting, it’s not a lay-down misère that the board will choose to move by 50 basis points, rather than reverting to its usual pattern of making 25 basis point moves...

[And] it’s yet to be seen how debt-laden Australian households will cope with the triple stress of rising prices, higher mortgage payments and falling house values. The Reserve Bank will be paying close attention to the slightest shifts in household spending patterns as it feels its way ahead.

Perhaps the biggest problem with monetary policy right now is the RBA's fixation with a so-called "neutral" cash rate, which it claims is at least 2.5%. The truth is the actual neutral policy rate is unknown: we will only know once we get there. Prior to the pandemic, the RBA thought a 0.75% cash rate was appropriate. It makes sense to search for a more neutral policy setting given Australia's 3-point-something-per-cent jobless rate, improving wage growth, and evidence that after delivering sub-par core inflation for a decade or so, underlying consumer price pressures might be higher once the spate of supply-side shocks subside. But given the enormous interest rate elasticity of Australian households and businesses, and evidence that confidence is cratering, a more prudent policymaker would proceed with caution.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 14 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

2 topics