Secular Stars: Why India and Indonesia are set to shine as global economic leaders

In 2013, India and Indonesia were notoriously named among the so-called “Fragile Five” emerging market (EM) economies that depend heavily on foreign investment to finance growth.1 A decade later, their fortunes have flipped: The two Asian nations are now seen as rising secular stars amid a challenging global economic outlook.

Growth in India is expected to outpace that of China this year and next – with Indonesia following closely behind in third place among major economies – according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In 2023, the OECD forecasts India to grow 6%, China to expand 5.4%, and Indonesia to grow 4.7%, while the global economy grows 2.7%.2

Over the secular horizon, we expect annual real GDP growth for India at 6-7% and Indonesia at 5-6% due to continued reform-oriented governance and macro stability. Both countries, with a combined population of 1.7 billion, benefit from younger demographics in contrast to the rapidly aging populations in China and developed countries. In spite of uncertain external conditions, India and Indonesia have effectively managed inflation and fiscal financing.

Against this backdrop, we see scope for currency appreciation and growth outperformance, along with increased capital inflows.

Here, we take a closer look at six themes driving growth in the two countries.

1. Demographics

The size and age of the workforces of India and Indonesia will play a significant role in their economic growth in the coming years. Each has a young and growing labor force that is expanding faster than the number of dependents, with 68% of both populations currently aged 15-64 years and only 7% above 65. In contrast, in more developed regions3, the old-age dependency ratio is much higher, with 20% above 65 years, and 64% aged 15-64.4 India alone will have over 1 billion working-age persons by 2030 and is expected to contribute about 24% of the additional global workforce over the next decade.5

The median population age is projected to remain under 40 until 2070 for Indonesia and 2057 for India, in contrast to 2027 for China.6 This translates to a competitive advantage not only in terms of workforce, but also an opportunity to unleash the consumption, savings, and investment power of a young population.

2. Infrastructure

Infrastructure development is crucial for India to achieve its 2047 vision of a U.S. $40 trillion economy and reclassification from a developing economy to a developed economy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Union Budget for fiscal year 2023-24 allocates 10 trillion rupees (U.S. $122 billion) to infrastructure development – five times the amount spent in the previous nine years. Studies by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy estimate that for every rupee spent on infrastructure, there is a 2.5 to 3.5 rupee gain in GDP.7

Infrastructure has also been a particular focus for Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo. Since he assumed leadership in 2014, there have been 2,042 kilometers of toll roads and 5,500 kilometers of non-toll roads constructed, as well as 16 airports, 18 seaports, and 38 dams, according to the president’s Cabinet secretariat.

3. Reforms

Modi’s sustained structural reforms are widely credited for helping the Indian economy enhance its overall efficiency, strengthen its fundamentals, and shed its “Fragile Five” tag. Bolstered by digital technology, the reforms are fundamentally aimed at improving the ease of living and doing business. They are guided by four broad principles: creating public goods, adopting trust-based governance, partnering with the private sector, and boosting agricultural productivity.

The 'Make in India' initiative launched in 2014 with the goal of making India a global manufacturing hub. With a transparent and user-friendly framework, and sector-specific production-linked incentives (PLI), it has helped foster innovation and increase foreign direct investment (FDI) in key sectors like railways, defense, insurance, and medical devices.

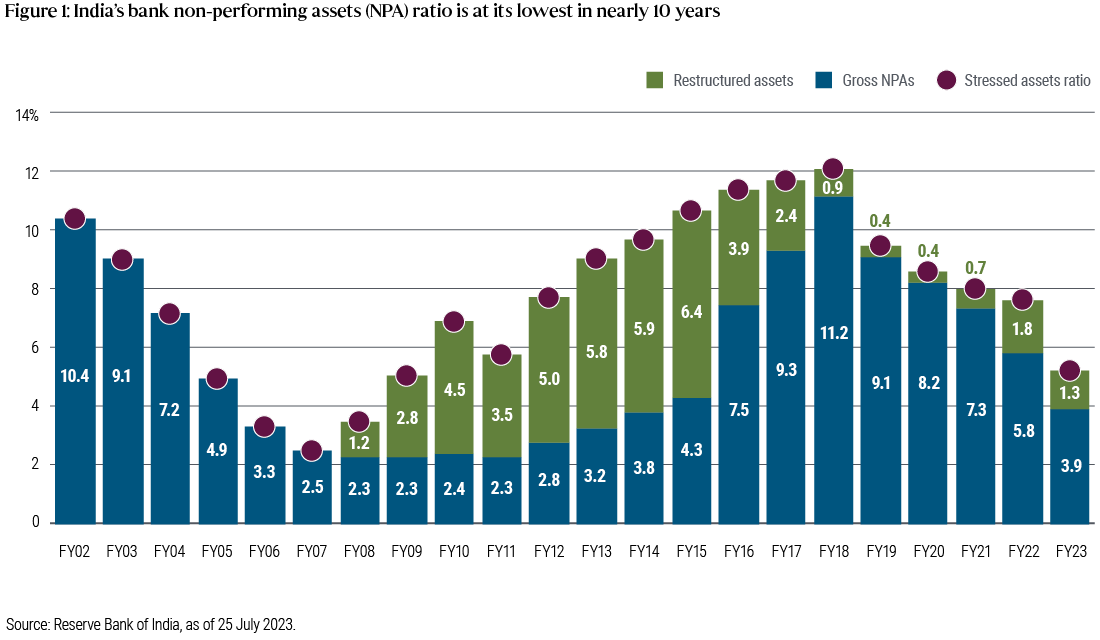

India’s macro stability has improved significantly since 2013, with the RBI building reserves and implementing effective liquidity management measures. Its flexible inflation-targeting policy, and central bank and government coordination on supply side measures, helped curb currency volatility and tame inflation without sacrificing growth. Its bank non-performing assets ratio is at the lowest in a decade (see Figure 1), bank profitability has improved, and corporate balance sheets have deleveraged. This will help ensure efficient credit provisioning, contributing to higher growth in the coming years through higher investments and consumption.

Indonesia’s turnaround has been driven by infrastructure investment, structural reforms, Bank Indonesia’s (BI) prudent policy mix, and the strength of its exports. Globally, the commodity boom has helped the resource-rich archipelago shore up its economic resilience and reduce its current account deficit.

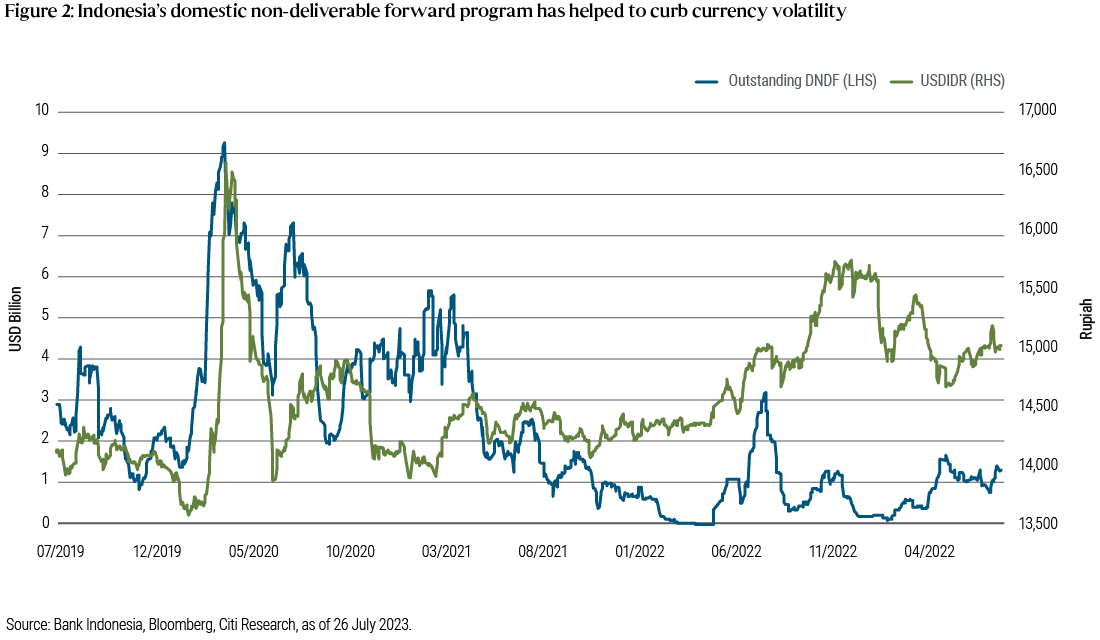

BI set up its domestic non-deliverable forward foreign exchange program, and promoted greater use of currencies other than the U.S. dollar in trade and investment. Regulatory and tax changes resulted in higher local investor ownership of government bonds. These measures helped to curb currency volatility (see Figure 2), and with its burden-sharing agreement ensured financing costs were manageable during times of stress. Meanwhile, government reforms have reduced restrictions for foreign investors, streamlined permitting processes, and lowered foreign investment limits, which helped increase FDI.

4. Shifting global value chains

As global companies adapt their manufacturing and supply chain strategies to build resilience in an increasingly fractured world, India and Indonesia stand to gain.

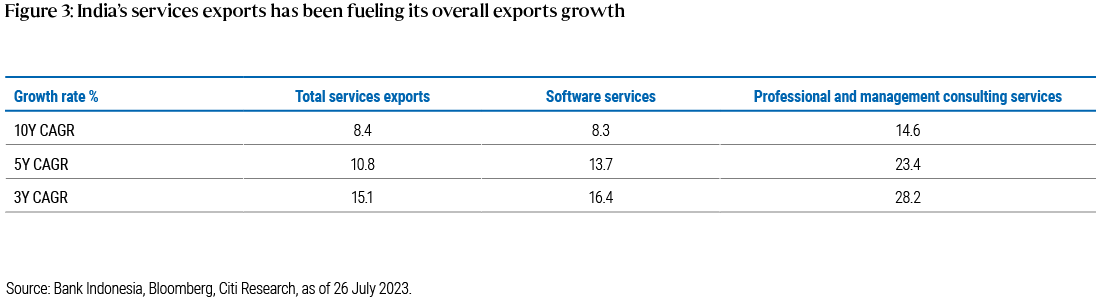

India’s services exports have been fueling overall export growth (see Figure 3), with a 14% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the last two decades.8 IT and business process outsourcing services make up 62% of total services exports. India has also become a leading global capability center (GCC) hub, accounting for over 45% of GCCs in the world outside of the home country.9 With a large talent pool and wages about 8-10 times lower than developed markets, we expect India to continue to gain share in global IT services spending.

As for goods exports, India has sectoral advantages in automotives, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, industrial machinery, and electronics. We expect manufacturing as a share of gross value addition (GVA) to grow to 21% of GDP over the next 10 years, vs. 16% in the last decade (9-10% real growth). Its manufacturing push and strong U.S. ties make India a top destination for firms’ “China-plus-one strategy”10. A sign of early success: India assembled a record $7 billion worth of iPhones last fiscal year, accounting for 7% of global iPhone production (vs. 1% in 2021), and expected to reach 25% in the next few years.

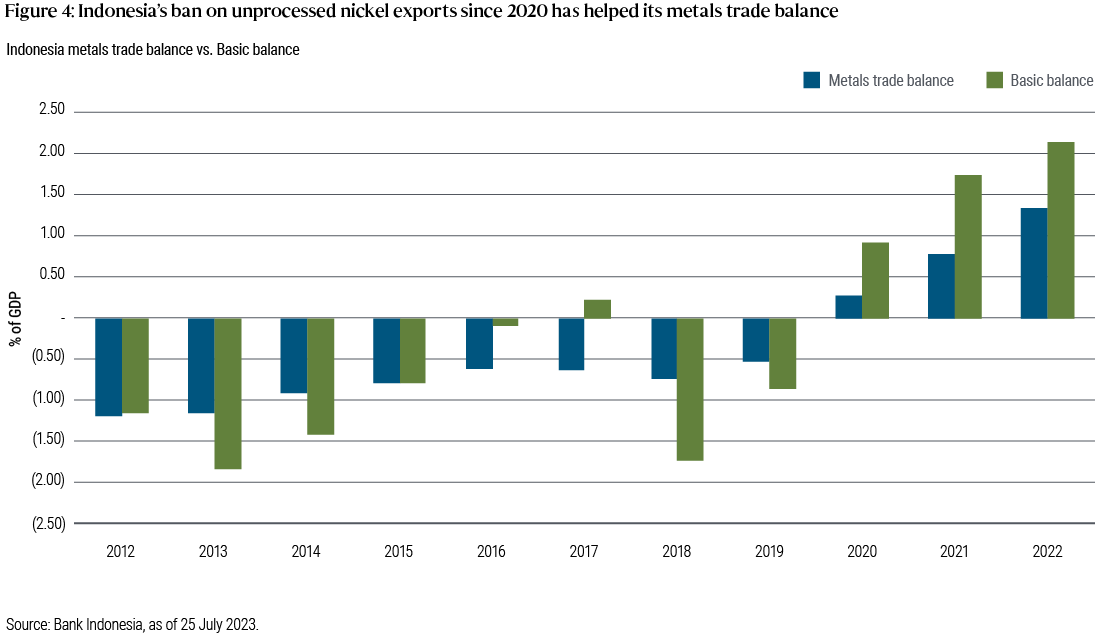

For Indonesia, further downstream processing of its natural resources would be a key driver of its growth potential, as shown by its success with nickel, a key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries used for electric vehicles (EVs). Home to 22% of the world’s nickel reserves, Indonesia’s ban on exports of unprocessed nickel since 2020 has lured foreign investment into locally-based processing plants and smelters, and enabled it to move up the resource value chain.

As a result, Indonesia has become a basic balance11 surplus economy on the back of drastic improvements in the metal trade balance (see Figure 4). Its exports of processed nickel have soared from $1 billion in 2015 to $30 billion in 2022, and it is expected to account for half the global production increase in nickel up to 2025.12 It is looking to replicate this success with bauxite, tin, and copper.

Tourism is another key focus area for Indonesia with the nation’s “Five New Balis” plan, which seeks to invest in and promote five "super priority” Indonesian tourist destinations, in order to further boost tourism receipts, which as of 2019 stood at just 1.6% of GDP vs. 11.3% for Thailand.

5. Energy transition

Indonesia’s advantage lies in commodities, buoyed by rising demand due to the global energy transition. By 2030, it is expected to be the world’s fourth-largest producer of “green commodities” used in batteries and grids, behind only Australia, Chile, and Mongolia.13

With its edge in nickel, Indonesia is poised to be Southeast Asia’s hub for the EV ecosystem. Coupled with aggressive growth estimates for EV domestic demand (based on Indonesia’s energy transformation commitments to reach net zero by 2060), we expect to see greater FDI flows into the country.

Meanwhile, India’s aggressive energy transformation agenda, especially with solar energy and its push for green hydrogen, should help drive India’s potential growth higher.

6. Digitalization

Prior to 2009, India had no nationally recognized form of identification. Today, more than 1.2 billion Indians (including over 99% of the adult population) have a biometrically-secured digital identity known as Aadhaar. Launched in 2009, the Aadhaar program is part of the “India Stack”, India’s open-source digital public infrastructure that also consists of complementary payment systems and data exchange.

The India Stack has been harnessed to foster innovation and competition, expand markets, close gaps in financial inclusion, boost government revenue collection, and improve public expenditure efficiency. Meanwhile, the “Digital India” initiative, launched in 2015, seeks to improve online infrastructure and increase internet accessibility for citizens, empowering them to become more digitally advanced.

According to European Commission data, the pace of digitalization in India was the fastest among most major economies in the world during 2011 to 2019.14 India’s digital economy grew at 15.6% CAGR from 2014 to 2019 – 2.4 times faster than the overall economy.15 In 2021, there were 48.6 billion real-time payments in India, compared to 18.5 billion in China.16 Digitalization has also enabled the growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which contribute almost a third of the country’s GDP, but have long struggled to gain access to formal credit.

Indonesia has also made enormous strides in digitalization – accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic – in terms of digital infrastructure, pro-digital legislation and regulation (such as the Digital Indonesia Roadmap for 2021-2024), and improvements in citizens’ digital literacy and proficiency. In 2021, there were 202 million internet users contributing U.S. $70 billion to Indonesia’s digital economy, with U.S. $146 billion projected in 2025. Similar to India, digitalization is accelerating the growth of Indonesia’s MSMEs, which contribute 61% of the nation’s GDP and provide employment for 97% of the total workforce.17

Implications for investors

India and Indonesia went through a series of reforms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic under the leadership of Modi and Widodo, which have played a key role in developing resilience in both economies. Both countries emerged strong from the pandemic and Russia-Ukraine crisis, which challenged their institutional stability and political resolve.

We believe currency valuations have not fully reflected these positive developments. Given favourable cyclical dynamics, we see scope for currency appreciation and growth outperformance, along with increased capital inflows. We expect stable sovereign credit ratings with a potential for an upgrade. However, due to taxes and tight valuations, we do not find duration and credit to be attractive in either country.

The 2024 elections in both countries pose a risk to our view should they usher in a change of government, but we broadly expect policy continuity.

Get the latest insights from the worlds premier fixed income manager

Be the first to read our latest Livewire content by clicking the 'follow' button below.. Want to find out how fixed income can play a role in your portfolio? Visit our website for more information.

5 topics