Sell CBA, buy JPMorgan? The trade Australian investors need to consider

Australian investors exhibit one of the highest levels of “home bias” globally—allocating 44% of their equity portfolios to domestic stocks. This is striking when you consider that Australian companies represent just a few percent of global equity market capitalisation.

To be fair, there are some rational justifications for this preference: franking credits, foreign dividend withholding taxes, and currency risk all make offshore investing less attractive on the surface.

And yes, we are fortunate - an entire continent rich in natural resources. But if necessity is the mother of invention, abundance might just be the mother of stagnation. It's no coincidence that Australia lacks meaningful global leadership in industries like AI, robotics, and biotech.

This domestic bias can come at a cost. We risk missing out on world-class opportunities beyond our borders. Take banking, for instance. Even in our strongest sector, there are superior alternatives abroad.

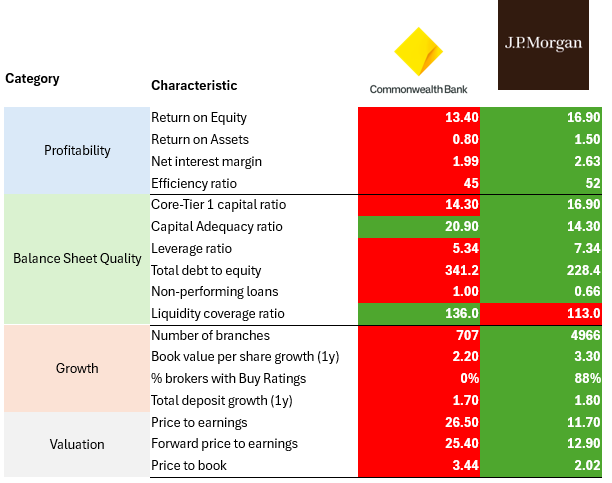

Compare Commonwealth Bank of Australia (ASX: CBA) with JPMorgan Chase (NYSE: JPM). Now, full disclosure: I spent 15 years at JPMorgan. But to keep things objective, let’s stick to the numbers. Across every major profitability metric, JPMorgan comes out ahead.

Its return on assets is 76% higher, and its all-important net interest margin is 32% higher. Both banks maintain high-quality balance sheets, but JPMorgan’s is exceptionally strong, with non-performing loans at just 0.66%.

Growth? Neither bank is setting the world alight. CBA is closing branches while JPMorgan is expanding. Deposit growth is roughly similar, but JPMorgan has a slight edge in book value per share growth.

And then there’s market sentiment: not a single sell-side analyst has a “buy” rating on CBA, while 88% are positive on JPMorgan. At this point, you might assume JPMorgan trades at a premium. But you'd be wrong.

CBA trades at a 126% premium to JPMorgan on a price-to-earnings basis. Its price-to-book ratio is 70% higher.

Academics often argue that markets are highly efficient—so mispricings like these shouldn’t exist.

One common explanation for CBA’s inflated valuation is the sheer weight of superannuation fund money and the rise of passive investing. But this logic has a flaw: passive funds buy stocks in proportion to their existing market weights, meaning this effect should be broad-based - not something that uniquely benefits CBA.

A more compelling explanation is behavioural.

Many long-term CBA shareholders bought in decades ago, have enjoyed strong returns, and now face significant capital gains tax if they sell. With no urgent reason to exit, they hold on.

This inertia may help explain CBA’s persistent premium.

Perhaps markets aren’t quite as efficient as textbooks would have us believe. Consider the curious case of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), one of the world’s largest companies.

It has shares listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange and an American Depositary Receipt (ADR) listed in the U.S. In theory, according to the Law of One Price, these two should trade at near-identical values. In practice?

As of yesterday’s close, the U.S.-listed ADR was trading at $32.68, while the Taiwan-listed shares were priced at $27.62 - a premium that has persisted for months.

Given JP Morgan’s global scale, strong fundamentals, and the potential tailwinds from U.S. deregulation and M&A activity we believe it is well positioned for future growth.

Finally, the steepening of the yield curve that we are witnessing is constructive for the company’s core business, borrowing short and lending long.

3 topics

3 stocks mentioned

1 fund mentioned