Should you trust ratings agencies?

BMO

Our investment objective is to grow our funds in hard currency over the long term by investing in companies that have sustainable business models and a long-term opportunity to compound earnings. A discussion of business sustainability naturally encompasses an analysis of risks and opportunities, under which we include environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Analysing these requires a subjective, in-depth review beyond just numbers and figures for which, increasingly so, investors request the services of ESG rating firms.

The industry has grown to such an extent that this ESG rating exercise has expanded to scoring investment funds as well as managers. The evolution of this market has prompted us to question the role these organisations play in our industry. ESG ratings systems are still in their infancy and we can easily envision them having a substantial impact on how capital is allocated in the future, not too dissimilar to the rise of the credit rating agencies.

History is littered with examples of the investment community over-complicating things with jargon and formulas. We have seen similar trends in ESG analysis, with various rating firms undertaking sophisticated ESG analysis on companies as well as funds, resulting in a simple rating that fails to capture the nuances of environmental and societal impacts. Unlike financial analysis, ESG analysis does not have a long history, and it is often not easily measured; it requires a subjective perspective to issues and often there is limited information available, particularly in emerging markets (EM). We see it more as an art rather than a science.

The situation has become so complex that today we have professional investors rating companies based on their internal ESG assessment, and these investors are subsequently rated by ESG ratings firms who rate funds based on their research of ESG factors. ESG ratings firms are then rated by think tanks and researchers on their rating quality. Confused yet? You may well be asking: what is the purpose of all this policing?

We often ask the same question. It worries us that ESG ratings appear to be justified by the ongoing growth of sustainable and responsible funds. It worries us further that some of these funds could simply be renamed versions of traditional funds to conceal mediocre performance. As a result, asset owners often struggle to tell the difference. The involvement of sales and marketing teams muddies the waters further. As a result, the industry is looking for an impartial referee who can tell the difference between what is genuine and what is not.

Two key players have emerged as referees: regulators (non- profit) and ESG rating agencies (for profit). Regulators are increasingly looking into this area - in Europe we have seen minimum standards and criteria implemented for funds that call themselves sustainable under the EU Taxonomy. The other parties potentially looking to profit from this are the ESG rating agencies, which we will now discuss.

So, who are these rating agencies?

The largest are MSCI ESG, FTSE Russell’s ESG Ratings, Sustainalytics (partly owned by Morningstar) and RobecoSam (recently acquired by S&P). There are also many smaller players, suggesting consolidation will eventually take place.

What do they do?

These firms score companies based on internal ESG parameters. Data collection is tedious, requires frequent updates, and is ultimately an exercise to try to fit data into the internal boxes each of the rating agencies has.

Where do they source the information from?

Information is sourced by rating agency analysts from what is publicly available. This leads to data quality challenges, as reporting from a $100bn developed market business will be very different than from a $1bn EM business.

Why do they exist?

To profit from a growing business need from the rapidly growing ESG asset class.

While we are supportive of better data quality and accountability, our experience with these agencies has so far been mixed. We worry that fund and stock selection decisions solely based on these metrics will not necessarily lead to better outcomes for investors.

Our three key concerns are:

1. Data credibility

Through our own review of portfolio companies in relation to rating agency datasets, we have seen wrong or outdated data bringing down scores, as well as subsequent inaction from agencies on correcting wrong data.

2. Irrelevancy of data

For example, the direct carbon emissions/footprint of a bank is important but nowhere near as important as whether that bank is funding coal projects or projects that do not adhere to minimum environmental standards. However, most rating agencies we have interacted with do not seem to have the resources to analyse – in depth – or factor in these unusual, yet highly relevant, metrics.

3. Comparing apples and pears

A typical challenge we face is by virtue of investing in EM. Often, these companies are run by entrepreneurs who are more focused on building businesses for many years to come, rather than helping out ESG score providers. As a result, some EM companies tend to under-report, or not report at all, which they are often penalised for (with score providers comparing, for example, a Nestle with a smaller operator on similar metrics).

We therefore encourage clients to perform extensive due diligence on the investment manager that they are considering entrusting their capital with, to be comfortable that the product truly follows the ESG strategy that its label suggests.

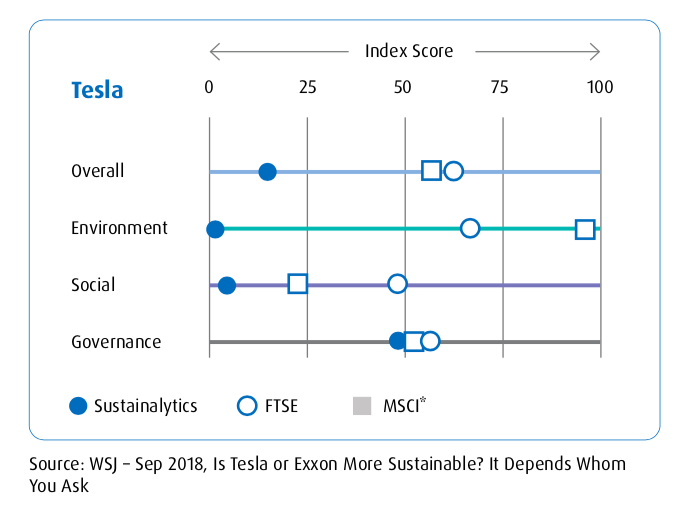

Let’s take Tesla as an example. Clearly electric cars are a complex beast; they eliminate roadside pollution, but raise questions in relation to the supply chain of some of the components as well as on the sources for the electricity that power them. In the US and Germany, around 80% of the overall energy production is from fossil fuels, so it could be argued that these fossil fuels are ultimately what power electric cars. There are also significant issues around battery sourcing and disposal. Below is an illustration of the issues we see. We would especially like to emphasize the environmental performance and how different it looks across the different agencies, highlighting the issues we raised earlier.

Conclusion

As a concluding remark on this subject (for now), we welcome the increasing scrutiny into our industry to ensure asset allocators buy exactly what is stated “on the tin.” But we also highlight that

assessing ESG factors requires subjective judgement rather than just a box-ticking exercise.

While scores fulfil a role, without subjective analysis, our concern is that ESG assessment will end up missing its intended purpose. As the saying goes, “the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

1 topic

Before joining LGM in 2006, Rishi worked with ICICI Securities and General Electric as an analyst researching the IT, Real Estate and Cement sectors. Since joining LGM he has researched Indian stocks and advised on our Indian mandates.

Expertise

Before joining LGM in 2006, Rishi worked with ICICI Securities and General Electric as an analyst researching the IT, Real Estate and Cement sectors. Since joining LGM he has researched Indian stocks and advised on our Indian mandates.