Sifting through the “massive” hype of US tax cuts

Jennifer Westacott, the CEO of the Business Council of Australia recently pointed out that if the US moves and other nation follow through with their pledges, Australia could become the 2nd highest taxing nation in the OECD.

On December 22, 2017 Trump signed off on arguably the first of his major campaign commitments – The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) – a $US1.5T cut in personal and corporate taxes. From a global investment viewpoint, the most significant feature of the TCJA was the big reduction in the US Federal headline company tax rate from 35% to 21%. In response, many commentators such as the BCA’s Jennifer Westacott have questioned how Australia can remain competitive given our relatively high corporate tax rate of 30%.

In this insight we analyse the impact of the US company tax cuts and provide a comparison to the Australian business context. Our analysis will primarily focus on the impact to large companies such as listed US companies and multi-nationals. Whilst US corporate tax payments will be cut significantly under the TCJA, we believe focussing on the headline US corporate tax cut number is quite misleading – significantly exaggerating the impact on corporate taxes for companies operating in the US.

Don’t ignore US state taxes

Unlike Australia, most US states impose their own personal and company taxes. Using sources such as the Tax Foundation and the Congressional Budget Office, we believe the total headline Federal plus state company tax rate in the US will drop from 39% to 25% rather than from 35% to 21%. This significantly reduces the difference in the Australian and US headline numbers – 30% is much closer to 25% than 21%.

Don’t fixate on the headline rate alone

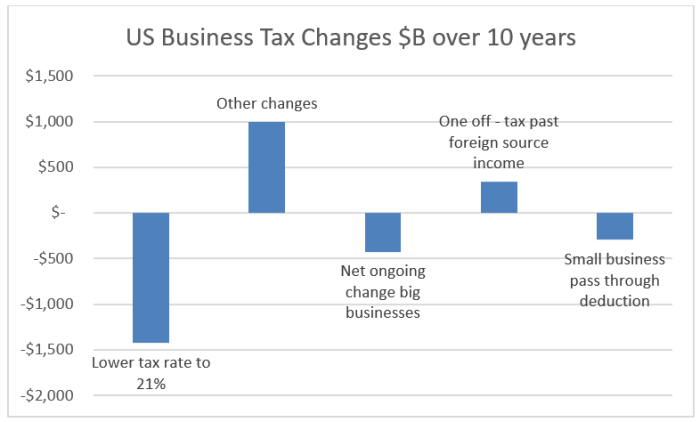

Commentators have tended to focus almost completely on the headline Federal rate reduction, which is, at 14%, literally “massive” and should in isolation significantly reduce company tax payments. The Tax Foundation (2) estimates that over 10 years, the headline reduction in rates alone will save US companies $US1,420B. However, this is a complex tax package that makes many other changes to deductions and imposes other taxes.

When the Tax Foundation estimates the total impact of all these changes, the net “business subtotal” reduction in taxes falls to a much lower $US373B over 10 years. However, we think to be fair we should exclude two business tax components from the “business subtotal”.

First, small businesses (think professionals working under a company structure) will benefit from a new 20% deduction for pass-through business income saving $US289B. This is unlikely to impact large companies and multi-nationals so we don’t believe we should count this benefit

Second, a new one-off deemed repatriation tax on past foreign-source income will cost companies who have sheltered income overseas $US339B. As an example, Apple Inc announced on January 17 that it would be providing for $US38B for past foreign-source income. Excluding these two items means the net ongoing benefit to large businesses is more like $US423B over 10 years, which again is substantially lower than the headline $US1,420B number. Whether we use either the $US373B or $US423B number, the net total impact when compared to the much larger headline number of $US1420B implies an effective reduction in net tax paid of 4% (rounded) not 14%.

Figure 1: Estimated US Business Tax Changes over 10 years from 2018

Source: Tax Foundation

Do focus on actual taxes paid

The Congressional Budget Office’s “International Comparisons of Corporate Income Tax Rates” (2017) provides another way of looking at corporate taxes, albeit the numbers relate to 2012. This analysis looks at both statutory tax rates and average corporate tax rates, which they define as “the total amount of corporate income taxes that companies pay relative to their income.” The CBO estimate that the statutory (Federal plus State) US tax rate was 39.1% in 2012, versus the average corporate tax rate paid of 29%. Australia’s top statutory tax rate was and still is 30%, but the report estimates the average Australian corporate tax rate paid was only 17%, substantially below the US average and the median of other G20 countries in 2012 of 21.8%.

Now, while we are making some broad assumptions here, if the TCJA reduces net taxes paid by approximately 4% (refer previous section), then this would reduce the CBO estimate of average tax paid from 29% (in 2012) to 25%. This 25% is still substantially higher than Australia’s average CBO tax paid rate of 17% (for 2012).

Don’t forget IMPUTATION

Many commentators, but not all (3), seem to have conveniently forgotten the impact of dividend imputation. Australian and New Zealand are the only countries included in the MSCI World Developed Markets Index that have a dividend imputation system. In Australia’s dividend imputation system, Australian company tax payments are credited to resident Australian investors to the extent that they have received franked dividends, and can then be used to offset normal personal tax.

In that respect one can think of Australian corporate tax as being a pre-payment of personal tax for Australian resident investors, assuming all tax paid income is fully distributed as franked dividends.

For a fully distributing company this means the effective corporate tax rate for Australian investors is zero. Yes zero!

Which is a whole lot less than the US rate of 21% or 25% and “massively” less than the Australian statutory rate of 30%. For example at the extreme, tax-exempt Australian investors such as charities or pension phase superannuation (up to the first $1.6m balance per person), receive a full tax refund of the value of these imputation credits (of Australian corporate tax). Plato estimates that franking credits have augmented the returns on the Australian stock market by approximately 1.5% pa over the past 10 years for a tax-exempt Australian investor.

Changes to Deductions and Other Taxes

Whilst we don’t have the time or space to provide a detailed definitive guide to all the changes in US corporate tax changes, we believe it is worthwhile to provide some detail on a few of the proposed changes outside of the headline tax rate change. In looking at these changes, we also believe there is far more positive “hype” than warranted. Many have jumped on the new 100% immediate deduction on the cost of new or used equipment investments. Yes, this will certainly encourage investment. But as inferred above, the Tax Foundation finds that the overall net effect of the tax changes outside the headline rate reduction is negative, not positive. Changes to deductions and new taxes offset almost 75% of the headline corporate tax reduction. The US already has many generous tax deductions, and, as part of the TCJA package, is winding many of these back, as well as introducing some new taxes. Here are some that caught my eye.

Limits on Interest Deductibility

Corporate interest expense deductibility will be limited to 30% of EBITDA (Earnings before interest tax and depreciation and amortisation) initially, and will later transition to a maximum of 30% of EBIT (Earnings before interest and tax), although there are exceptions for financials and regulated utilities. We estimate using latest financial year data, that this change may potentially impact $US25B of annual interest deductions on approximately 2200 listed US companies which we follow.

Motivations for this limit appears to be to reduce excessive leverage, and more importantly to reduce multi-nationals from using excessive debt and/or interest rates on that debt to shift profits to lower tax regimes. This is also an issue in Australia, and this type of limit may potentially provides a solution for Australian tax legislators.

Effective Minimum Tax Rates

Two other initiatives are designed to limit corporate global tax minimisation via profit shifting. The first measure imposes a minimum tax rate of 10.5% on the overseas earnings of US multi-nationals in excess of a routine return on tangible investments. This is particularly aimed at US companies moving their intangible assets to low tax regimes. The second minimum tax rate of 10% is on an alternative income measure that excludes payments to foreign affiliates, for domestic US companies with large payments to foreign affiliates. This aims to limit transfer pricing abuses, where companies potentially pay over the odds for goods received from affiliates in lower tax regimes.

Loss Deductions Limited

Carry forward loss deductions will be limited to 80% of taxable income, and loss carry-backs are to be eliminated.

Changed Limits to Executive Compensation Deductions

Whilst very small in the scope of things, this change did catch my eye. US companies already have some limits in place on the deductibility of executive compensation. Currently the maximum deductions allowable for base salaries for the CEO and three other highest paid executive officers (excluding the CFO) is $US1m per executive, but these limits only apply to base salary, not performance pay. Perhaps this may help explain why US performance based pay forms a very large part of execution compensation? Going forward, the performance pay exclusion will be dropped, and the executive coverage will increase to include the CFO. It may be interesting to see whether this tax changes alters the mix between base and performance compensation components.

Summary

US President Trump has delivered one of his major election promises – a “massive” $1.5T tax cut for individuals and companies. For companies the headline tax rate reduction is also a “massive” 14%, taking the US Federal headline corporate tax rate down from 35% to 21%, some 9% lower than Australia’s corporate tax rate. However, after incorporating the impact of US state corporate taxes, the US headline rate will fall to around 25% (from 39%) not 21%. However, the TCJA does more than change headline rates, making numerous changes to corporate deductions and imposing a number of new company taxes. When one looks at the totality of the overall package, the Tax Foundation estimate that the net impact on corporate taxes will be around 25% of the headline tax reduction. Using Tax Foundation numbers, we estimate the impact of corporate tax paid will be more like a 4% reduction in the average corporate tax rate paid, not 14%. So yes there is a significant fall in US corporate taxes, but much less than the “massive” headline rate reduction implies.

The impact of the taxes will differ between companies. Multi-national companies that currently shield profits from high US tax rates via transfer pricing, moving intangibles to low tax regimes or using high levels of debt to minimise income will likely get less benefit, whilst domestic focussed companies may likely capture maximum gains.

And finally, Australian resident investors should not forget that Australia’s dividend imputation system means that the corporate tax rate on distributed Australian company profits is not 30%, not 21% nor 25%, but is effectively zero!

To access further insights from Plato Investment Management, please visit our website

Footnotes

(1) As reported in the AFR “Donald Trumps’s historic tax cuts pass Congress” Dec 21, 2017.

(2) (VIEW LINK) All numbers in this section are sourced from this source based on in static revenue basis numbers

(3) “Business tax cuts don’t make sense, Former RBA board member John Edwards”, AFR, Jan 7 2018.

5 topics