State bonds increasingly becoming a safe haven asset and credit hedge

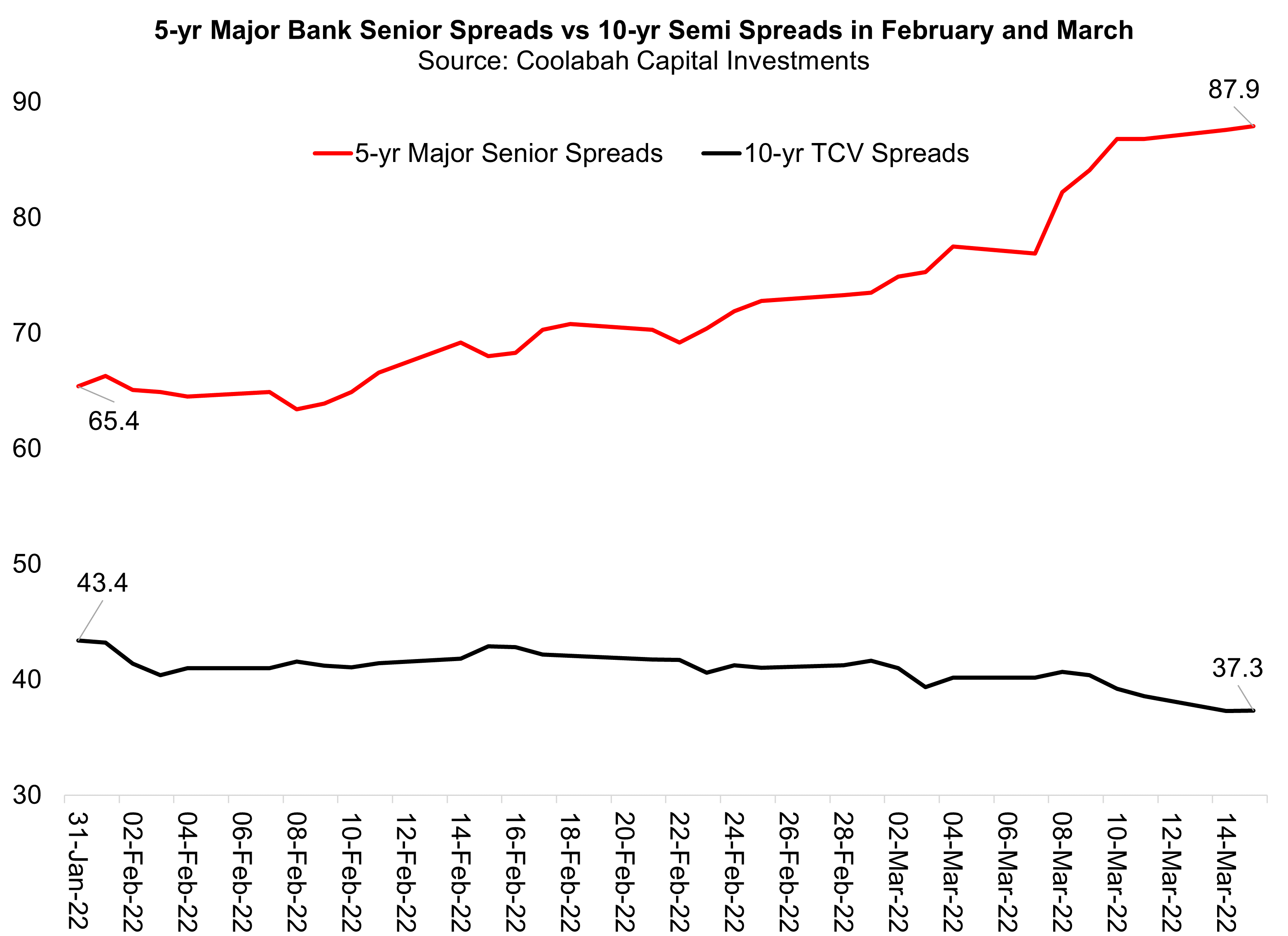

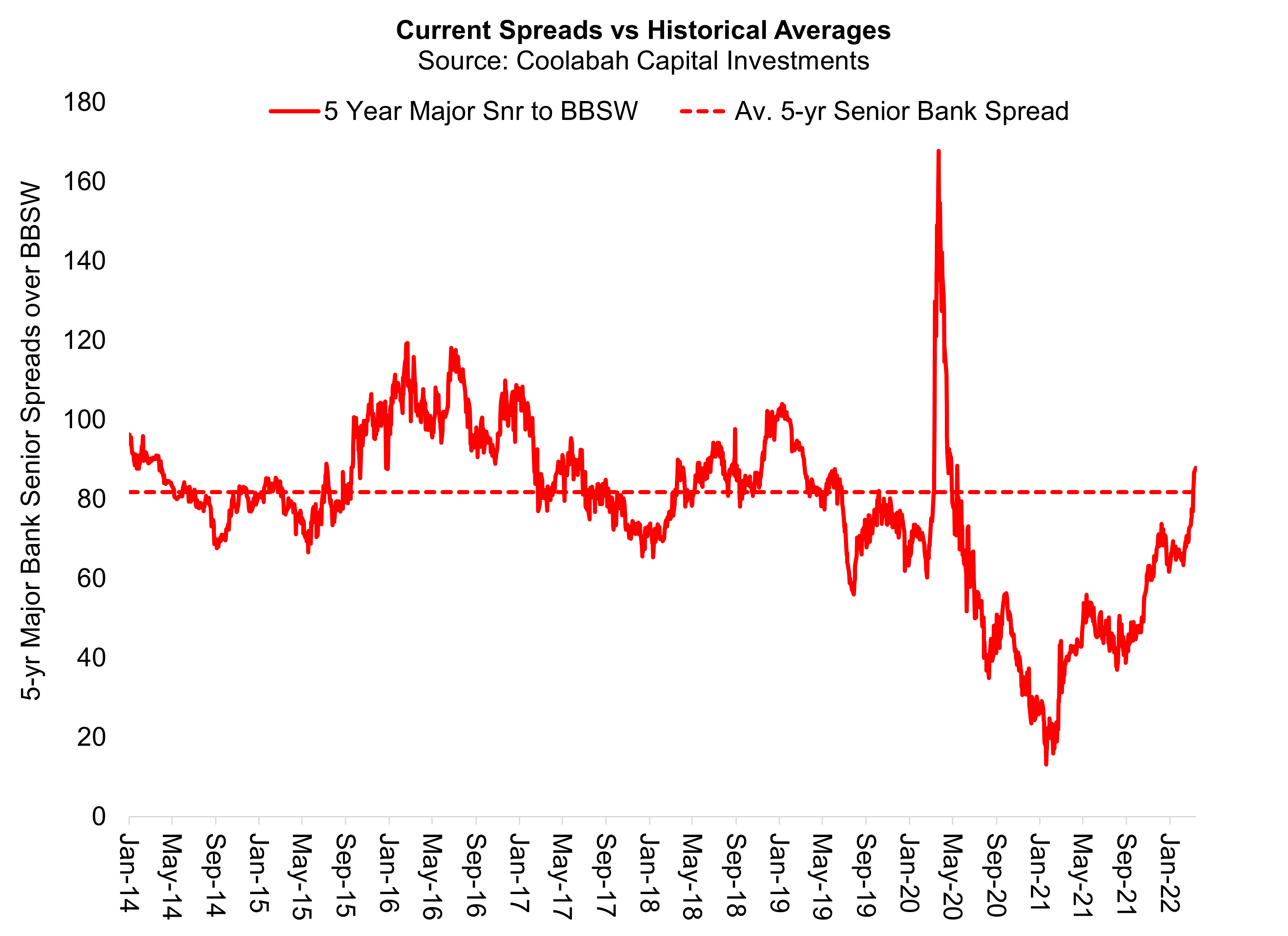

Bank traders have frequently reported AA to AAA rated State government bonds (or semis) have been increasingly behaving like a "safe-haven" asset as the spreads they pay above Commonwealth government bonds have declined over the incredibly volatile months of February and March while credit spreads globally have exploded. Australia has not been spared: 5-year major bank senior bond spreads have jumped some ~23 basis points (bps) since the start of February and are about ~60bps wider than the record lows touched in early 2021.

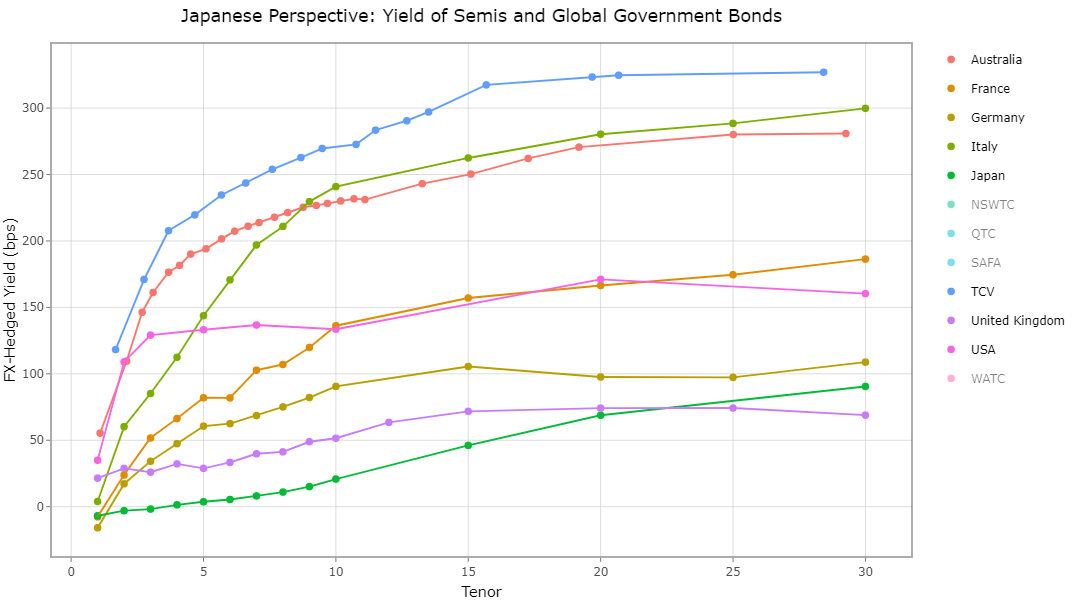

Regular readers will recall that we have been negative on Aussie bank senior spreads since the start of last year, at times carrying as much as $1 billion of hedges against the sector. The outperformance of State bonds over traditional credit has been driven by unrelenting buying of these bonds by banks for regulatory liquidity purposes, which we had long projected, and by foreign, especially Asian, investors attracted by the fact that AAA and AA rated semis pay the highest FX-hedge yields of any similarly-rated government bonds globally. This is because Aussie 10-yr Commonwealth government bond yields offer about ~40bps in extra interest above US treasuries, and this margin doubles to circa ~80bps in the case of bonds issued by Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria. For Japanese and Taiwanese investors, this yield pick-up has been too good to refuse. (The image below is a screen-shot from our internal systems.)

Australia and its individual States have also been a unique beneficiary from the conflict in Europe, profiting from higher commodity prices (wheat, iron ore, coal and LNG) and the perception that we are relatively insulated from these ructions. It is likely that one second-order consequence will be a surge of skilled immigration into Australia looking for a prosperous and more politically stable alternative to the Continent, which the Commonwealth government is very keen to promote. This will support population growth, which will further drive Australia's robust expansion.

There is also increasingly chatter that global asset-allocators are pivoting to Australia as a high-yielding safe haven vis-a-vis the volatility embroiling Europe, which is evident in the outperformance of the Aussie dollar over its US counterpart. (You can review our geo-political analysis and forecasts for Russia and Ukraine by clicking here. We've also published an update on the risks of Russia defaulting on US$150 billion of its debts here.)

How different are State bonds to "credit" (eg, senior-ranking bank bonds)?

For the sake of exposition, let's compare spreads on State bonds with the spreads on lower-rated, senior-ranking bank bonds. Technically, semis sit in the sovereign/treasury sector while bank bonds are considered "credit", although they both trade at (or pay) a margin, or spread, to various benchmarks for the risk-free rate.

We specifically contrast 10-yr semis with 5-yr major bank senior bonds (these tenors are considered the most liquid benchmarks for each sector). And we evaluate data post 2013 to capture the anticipation and introduction of APRA's Basel 3 liquidity framework, which impacted the spreads on bank bonds and semis.

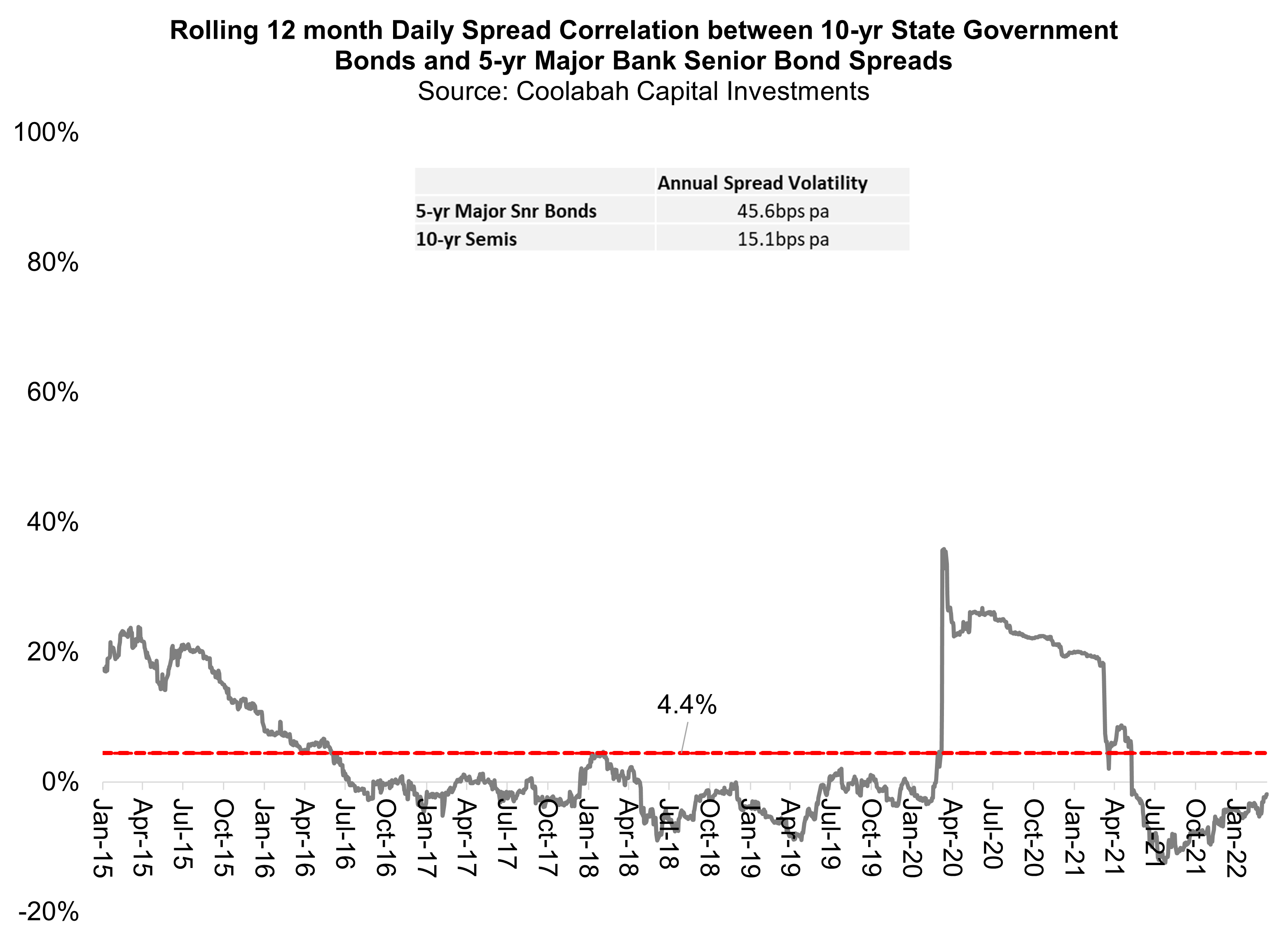

The first chart below shows the rolling 12-month correlation in daily spread movements for 5-year major bank senior bonds and 10-year Victorian government bonds. (These are constant-maturity indices that we calculate inhouse.) Spreads are evaluated relative to a cash rate benchmark to remove the influence of swaps. Since 2013, the spread correlation between semis and bank bonds has been statistically indistinguishable from zero, which is not surprising given we are contrasting government-guaranteed bonds with generic credit.

The spread correlation averages 4.4% since 2013 and has actually been negative since 2021. There was a temporary spike in March 2020 to north of 30%, although this disappeared once the RBA started buying State bonds as part of its bond purchase program (aka "QE"). Significantly, the RBA did not buy credit, or bank bonds: only Commonwealth and State bonds were eligible.

Over and above the near-zero correlation between the sectors, the annual volatility of their spreads above the cash rate is also quite different: 5-year major bank senior bond spreads have displayed significantly higher 46 basis points (bps) annual spread volatility compared to 15bps for semi spreads. Now this is just spread volatility: to compute price volatility, we need to adjust for the different durations of the 5-yr major bank senior and 10-yr semi benchmarks. Doing so gives us price volatility for the major banks' senior bonds of ~2.06% annually and ~1.36% annually for the semis.

Different risk drivers

The near-zero correlation and contrasting observed volatility of the two sectors make sense given they have distinct underlying risk attributes:

- The semis get the benefit of credit ratings of AA to AAA across the three rating agencies, which are higher than the major banks' A+ to AA- ratings;

- Semis are government bonds with extensive revenue-raising powers whereas bank paper is backed by an individual deposit-taker. As noted above, semis were explicitly acquired alongside Commonwealth bonds by the RBA via its three QE programs between 2020 and 2022 (bank paper and corporate bonds were excluded);

- The underlying investor cohorts are also very different: whereas semis sit in sovereign/treasury portfolios, bank senior paper resides in credit books, which are normally managed by different teams;

- Semis count as a Level 1 "high quality liquidity asset" (HQLA1) for the banks' regulatory liquidity requirements---bank senior paper does not (in the case of Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) compliant banks). This means LCR banks buy semis, but not bank bonds, for their liquidity books; and

- In the past, banks did buy bank bonds as a substitute for HQLA1 as part of the >$200bn Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF). But since APRA announced the CLF would be progressively closed over the course of 2022, banks will no longer be able to buy one another's bonds for their liquidity books (the CLF had been reduced to $140bn in size by December 2021 and will fall to zero by the end of 2022).

Are current spreads cheap?

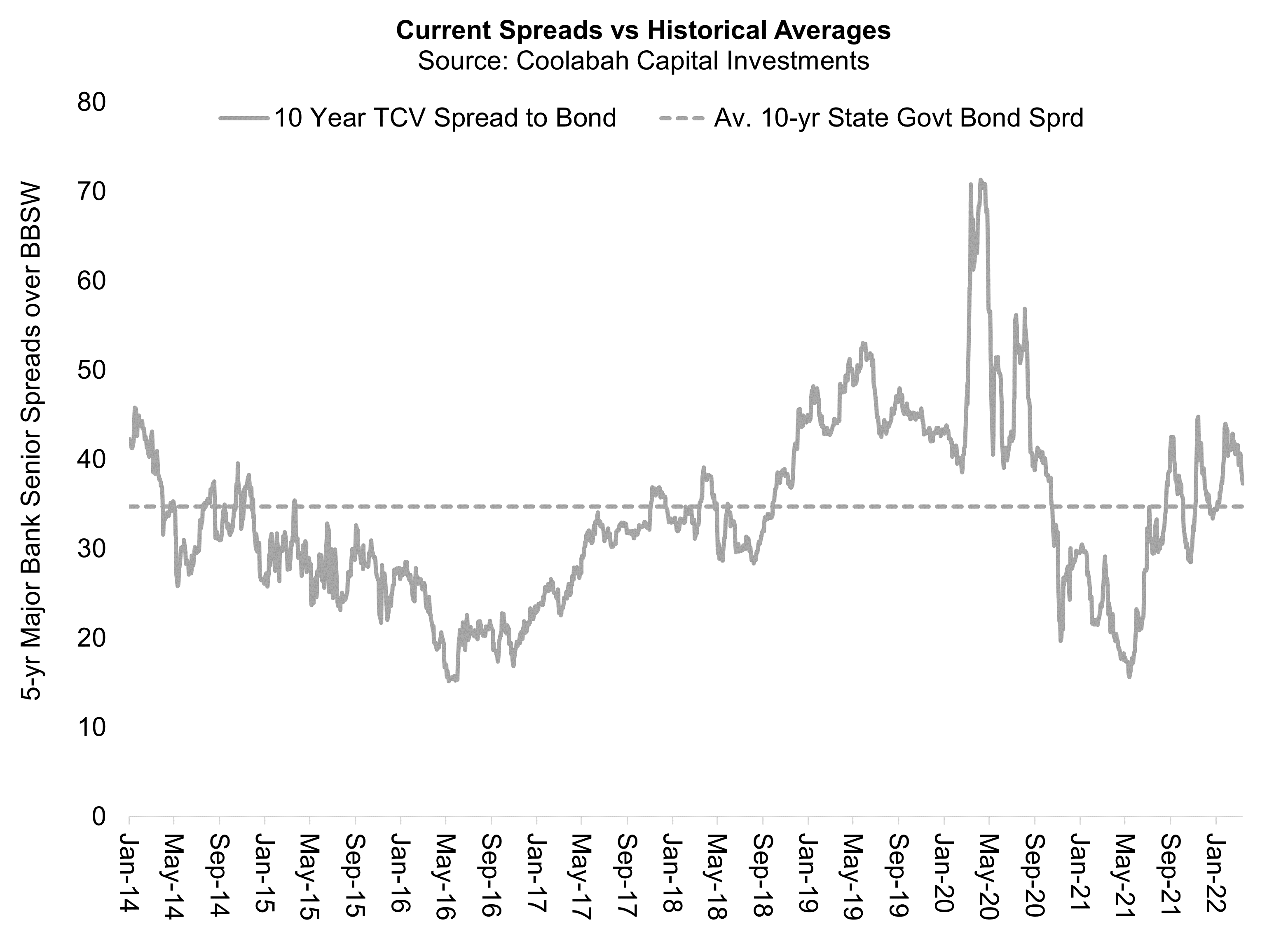

This brings us to current spread levels and whether they look rich or cheap. As a starting point, one can compare current spreads with their historical heuristics.

We've excluded the post-COVID period to remove the impact of the RBA's QE program on semi spreads, which compressed spreads from circa 40bps over Commonwealth bonds to as low as 15bps. By removing the post-COVID data we also strip-out the impact of the $188bn of money the RBA lent the banks via the Term Funding Facility (TFF), which resulted in banks radically reducing debt issuance. This paucity of supply drove 5-yr major bank senior bond spreads down from circa 60-70bps pre-COVID to as low as the 20-30bps area afterwards.

10-yr semis are currently trading at about ~38bps over Commonwealth government bonds, which is above the 33-34bps average level observed between 2014 and 2019 (inclusive). Similarly, 5-yr major bank senior bonds are trading at ~88bps, which is ~6bps above the 2014 to 2019 average of ~82bps. So both sectors appear somewhat cheap relative to their historical average levels. But they have radically different demand and supply outlooks: in particular, semis will benefit from reduced supply combined with a huge increase in demand via "bank-directed QE", which will dwarf the RBA's QE program by a factor of 2.5 to 4.9 times. Bank bonds will, on the other hand, suffer from a sharp rise in supply coupled with diminished demand...

Very different demand and supply outlooks

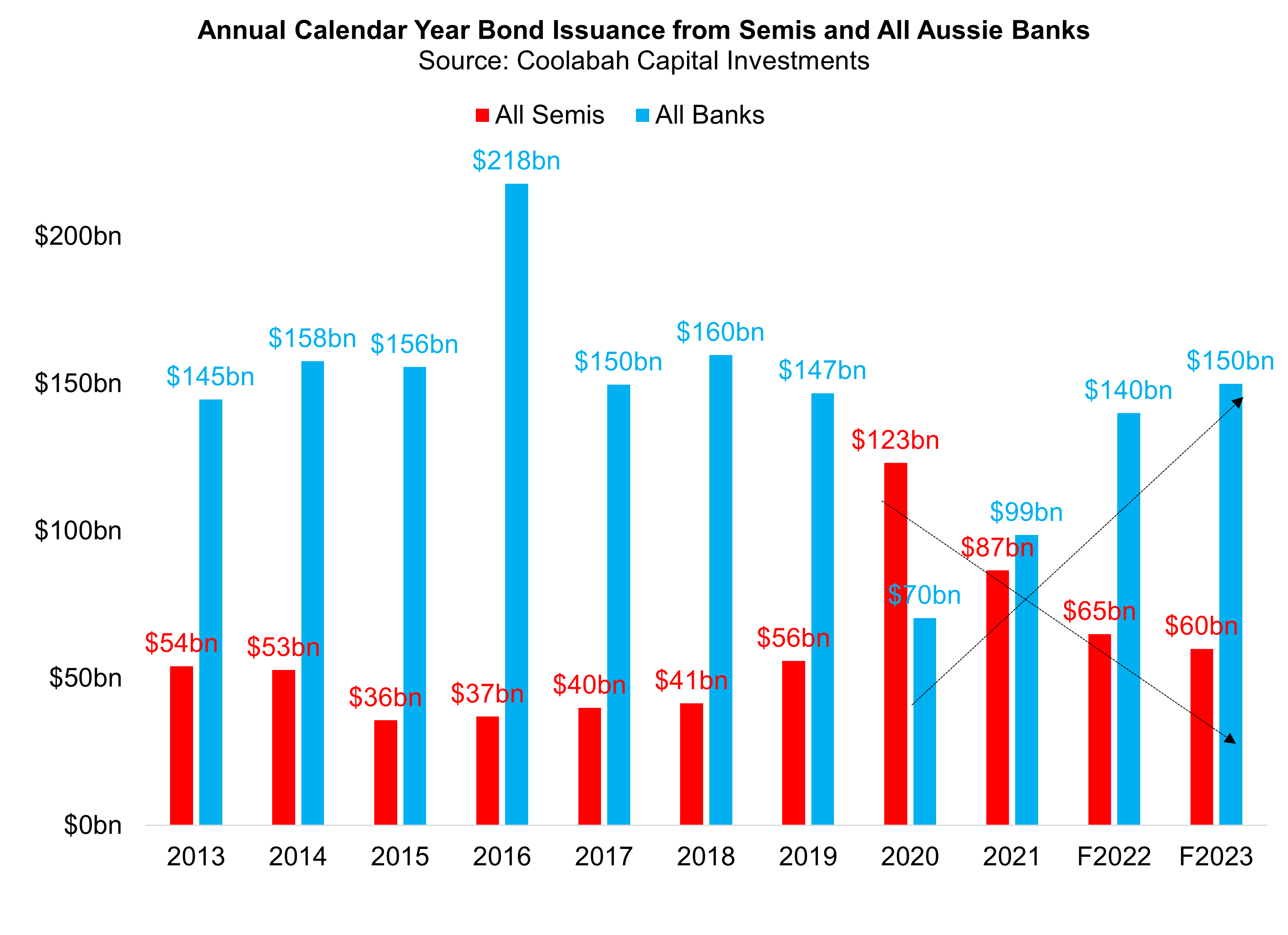

On the supply-side, we know that banks are very aggressively increasing their debt issuance off the low, TFF-suppressed levels in 2020 and 2021 to secure funding to finance the purchase of new HQLA to replace the $140bn CLF (about 80% of the CLF was made-up of internal bank loans that were self-funded) and to prepare for the repayment of the $188bn TFF. Banks have been quite transparent in stating that they expect debt issuance to climb back to the levels observed in the pre-COVID period. The need to issue debt is being reinforced by faster than expected balance-sheet growth, which probably explains some of the new debt issues suddenly announced by the major banks and Macquarie in USD and EUR in recent weeks.

At the same time, the States are slowly pulling back on their debt issuance from the CY2020 peak of more than $120 billion. In CY2021, this fell to $87 billion and we are projecting that in CY2022 the States will only issue circa $65 billion with CY2023 falling further to $60 billion. It was telling that the States only announced ~$35 billion of issuance for the first half of CY2022, and more recent monthly budget data implies this will have to be revised down quite materially over the remainder of the year.

Our chief macro strategist, Kieran Davies, found that based on the latest January financials, NSW's deficit is likely to be $4bn to $5bn lower than the government's full-year forecast, even allowing for the costs of recent tragic flooding and higher capex. The Victorian budget data in January echoed the NSW result, narrowing sharply and is on track to beat the State's full-year forecast by about $2bn. State budget outcomes are firmly skewed towards lower deficits as commodity prices, including wheat/iron ore/LNG/coal, immigration, and national economy's strength, accented by the jobless rate printing this week at just 4.0%, drive much better than expected revenue outcomes. We will be publishing updated analysis on our semi supply expectations for 2022 and 2023 soon.

$280bn to $550bn of bank-directed QE

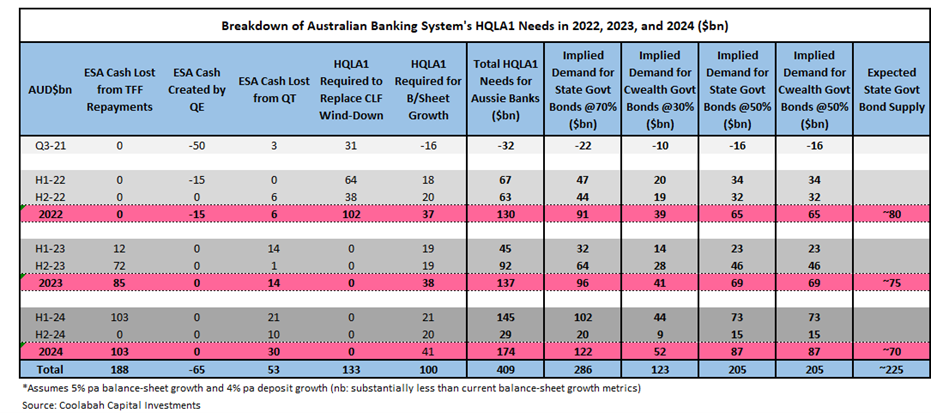

Whereas banks are losing the all-important balance-sheet bid from the $140bn CLF, which used to be north of $200bn, semis directly gain this demand given banks have to replace their CLF portfolios with new HQLA1 assets.

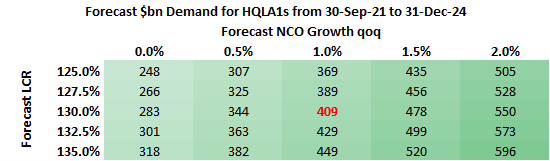

Our credit researchers have published a lot of pioneering analysis on precisely how big the HQLA1 hole is for the banking system, which we estimate ranges between $280bn and $550bn over the next 3yrs. Based on past behaviours, around 70% of this should be allocated to semis with the remainder going to Commonwealth bonds. All told, the banking system should have appetite to buy most, if not all, of the dwindling supply of bonds issued by the States.

.png)

Buying 70% to 140% of annual supply

To put this in perspective, the RBA only bought $56bn of State bonds during its first three QE programs. If we conservatively assume that banks only allocate 50% (rather than the typical 70%) of their HQLA1 needs to semis, they will still need to buy between $140bn and $275bn in the next 3 years, which is the equivalent of 2.5x to 4.9x the totality of the RBA's three QE programs combined. And given reduced debt issuance needs from the States, that translates into banks buying somewhere between 70% and 140% of annual semi supply...

4 topics