State debt issuance in FY23 reduced from original $86bn estimate to $68bn

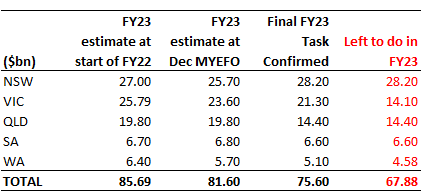

We have now received the big five state budgets and can assess proposed debt issuance relative to what they projected for this coming FY23. The short story is the states were expecting to issue $86bn in FY23, which has been meaningfully reduced to $76bn, as we had expected. Accounting for pre-funding as we head into FY23, actual issuance that remains is only $68bn (or one-fifth less than the original $86bn estimate). Capex delays and the sheer difficulty rolling-out spending programs will revise issuance down further, especially considering budgets like NSW's have actually adopted quite conservative forecasts assuming a sharp slowdown in the housing market. There is further conservatism in the assumptions underlying the QLD and WA budgets, where commodity prices are projected to quickly mean-revert back to normal levels, which is unlikely.

Queensland better, NSW worse, net better

Queensland and NSW released their budgets yesterday. In the case of Queensland, proposed issuance of $14.4bn was a material $5.4bn less than they estimated in December ($19.8bn). Conversely, NSW was a downside surprise, with the proposed issuance of $28.2bn being $2.5bn more than NSW estimated in December ($25.7bn). Having said that, NSW's FY22 budget deficit was $7.5bn less than NSW estimated in December, almost exactly in line with CCI's estimates. Net net across the two State results yesterday, debt supply was $2.9bn less than the combined supply estimated from NSW/QLD in December. There are swing factors with NSW in particular in terms of how much money they can practically spend, and in respect of whether they further draw-down on the $15bn in cash in NSW's Debt Retirement Fund, which we believe is likely.

The table below summarises the results for the big five states. At the start of FY22, the States estimated they would issue about $86bn of debt in FY23. In December, this was revised down to $82bn. And in the final budgets, it has been aggressively revised down again to $75.6bn. Importantly, because VIC and WA have already started their FY23 programs, with VIC in particular getting off to a flying start with its jumbo, $4.4bn FRN deals, the remaining State supply in FY23 is only $67.9bn, or about one-fifth less than the original FY23 estimate of $86bn at the start of FY22. CCI has been forecasting that State debt issuance would be in the low $70bn to high $60bn area in FY23 for quite a while now.

There are, of course, the remaining smaller States and Territories (NT, ACT, and TAS), although their programs tend to be rounding errors. There is also a case that the States might do some pre-funding in FY23 for FY24. But in the last three financial years, States have not issued materially above their official funding programs: pre-funding has come in the form of budgets outperforming the typically conservative forecasts, which have, in particular, systematically over-estimated (by quite a massive margin), the extent to which States can roll-out their ambitious capex plans.

FY23 Issuance Likely to be Downgraded Further

Our chief macro strategist, Kieran Davies, has published research quantifying the precise delays in capex roll-outs over time based on past budget data, which are fairly consistent/systematic:

Our research indicates that issuance of state government debt is likely to be between $8bn and $16bn lower than the market expects in FY2023 (or 2022-23 in budget terminology) because history demonstrates that infrastructure projects regularly take longer to complete than planned... Sharply higher debt servicing costs could also restrain public spending with the interest rate on NSW's benchmark 10-year bonds more than tripling from as little as 1.5% in August 2021 to closer to 5% today.

Davies judges that the State budget forecast assumptions are universally quite conservative, especially in the case of QLD and WA where commodity prices are assumed to rapidly mean-revert, which is unlikely. In the case of NSW, Davies believes that actual issuance is likely to be materially less than the official funding task simply because it is not possible to spend the money NSW has committed over the next 12 months. "As one example, the government is unlikely to be able to spend as much on health as intended, where planned hiring of additional health workers will be difficult given health-sector job vacancies are already at a record high," Davies says. He notes that with NSW there has been a pattern along these lines, exemplified in FY22:

- NSW originally announced $36bn of proposed issuance for FY22

- They revised FY22 issuance down to $27.4bn in December;

- And they only ended-up issuing around $19bn for FY22.

This was a key CCI forecast: in mid 2021, we argued that NSW's proposed $36bn program would be slashed down to the low $20bn or high teen area. This was partly driven by our forecast that NSW would stop issuing debt to fund the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund (ie, stop the proposed levered carry trade that would have turned NSW's balance-sheet into a hedge fund), which they agreed to do in September 2021, and that they would go one step further and actively draw-down on the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund, which they also agreed to do last year. In particular, they are drawing on $11bn of the $26bn DRF. Of this $11bn, there is $3.3bn remaining, which will be used in FY23.

In the latest NSW budget, they have made the important decision to defer making any additional contributions to the NGF's Debt Retirement Fund until FY24. We continue to forecast that NSW will not divert revenues back to the Debt Retirement Fund until they are in a cash budget surplus, after accounting for capex.

We think the NGF's $15bn Debt Retirement Fund will rapidly come into focus because of the looming March 2023 election. A few forecasts in this respect:

- We project that NSW Labor will opt for fully utilising the $15bn Debt Retirement Fund to repay the massive amount of debt that has been racked-up by the Perrottet/Kean government. Note that this $15bn is exposed to equities and other risky asset-classes, and has lost money in FY22, as it did in FY20 (it has only made money in one year over the last three). NSW also lost money in the Debt Retirement Fund by lending to authoritarian regimes like Russia, Saudi Arabia, UAE and China, which is completely inconsistent with its legislated purpose.

- NSW debt has jumped from $38bn in 2018 to over $110bn today (ie, increased by more than $70bn). On new 10yr debt issues, NSW's borrowing costs have also surged from 1.5% pa last year to circa 5% today. Fully utilising the $15bn Debt Retirement Fund to repay debt, and avoid $15bn of future issuance, will save NSW taxpayers as much as $750m/year in interest repayments.

- One way or another, we believe Perrottet/Kean or a future Labor government will use the Debt Retirement Fund for its sole legislated purpose, which is not to punt stocks, or lend money to Russia: it is to repay NSW debt; help maintain NSW's AAA rating, which was lost in 2020 due to Perrottet/Kean's debt binge; and to reduce NSW borrowing costs, which have sky-rocketed under the current government.

One final word on the State budget forecast assumptions. Our chief macro strategist Kieran Davies comments:

- For NSW, the revised economic forecasts are reasonable, capturing the stronger-than-expected labour market and higher inflation. House prices and home sales are assumed to fall sharply now that the RBA is raising interest rates, with unemployment rising slightly by the end of the forecast horizon.

- On Queensland, like NSW, the forecasts appear conservative, especially given that Queensland's budget assumes a normalisation in coal prices where the risk is clearly that they remain elevated for a protracted period. This echoes what WA has done in respect of its commodity price forecasts, which are extremely conservative.

4 topics