State government bonds transition from RBA QE to bank QE in 2022 and beyond...

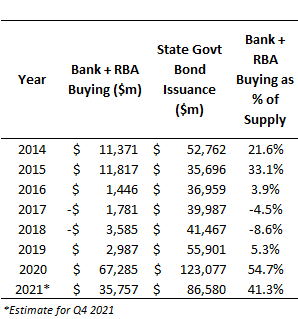

Since 2014, banks have typically bought a large chunk of all new State government bond ("semi") issuance, with a peak of 49% in 2020. Our analysis suggests that as a result of new liquidity requirements, banks will have to materially up the ante on their semi bond buying if they are to minimise net interest margin and return on equity drags, taking down most, if not all, of the supply, over the next few years.

Notwithstanding persistent buying over the month, semi spreads over Commonwealth government bonds have in January steadily climbed to elevated levels as the street has actively sought to cheapen-up the sector ahead of the RBA ending its bond purchase program, also known as quantitative easing (QE), on the 1st of February. Technically, the RBA's bond buying does not end until "mid February", which implies there will be another 2-3 weeks of QE purchases before the program ends.

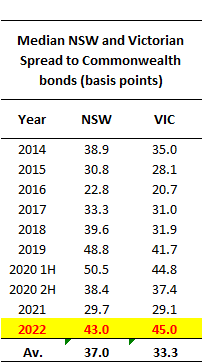

The first table below shows the median calendar year spread on a NSW and Victorian 10-year state government bond over the maturity-matched Commonwealth government bond curve over the last decade or so. The average 10 year semi spread (called a "g-spread") has been 37 basis points (bps) in the case of NSW and 33bps in respect of Victoria. Current 10-year spreads for NSW and Victoria are sitting at circa 43bps and 45bps, respectively. This is materially above the medians in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and during the second half of 2020 and the duration of 2021. The only time we have seen higher spreads on a sustained basis was during the pandemic shock in the first half of 2020 and in 2019. That is, the market has completely removed the influence of QE from current semi-spreads, normalising back to levels above the long-term average.

Spreads are ultimately determined by supply and demand. Banks have typically been large buyers of State government bonds for their liquids portfolios for over a decade. APRA requires banks to hold more than 100% of their expected Net Cash Outflows (NCOs) in a 30 day liquidity shock in the form of Level 1 high quality liquid assets (HQLA1). This is known as the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) test. HQLA1 is normally made-up of Commonwealth and State government bonds, with banks holding these assets in a 30:70 ratio given the much higher yields offered by semis. It is clear in periods where bank buying of semis is large, such as in 2015 or 2021, relative to semi supply, that spreads trade much tighter.

This naturally brings us to the demand vs supply outlook for 2022 and the years ahead. We've done a lot of detailed modelling about the amount of HQLA1 the banks will need over the next 3 years, which banks broadly concur with. You can read a full summary of our modelling here. In short, banks need HQLA1 to:

(1) replace the $140 billion of liquidity they currently get via the Committed Liquidity Facility, which will shut at the end of 2022,

(2) replace the $188 billion of digital cash they have to repay the RBA (via the Term Funding Facility) over the next 3 years, which currently counts as HQLA1,

(3) replace the digital cash they lose, which is included in HQLA1, as bonds mature off the RBA's balance-sheet (this is worth some $6 billion in 2022 alone and $56 billion over the next 3 years), and

(4) contribute to new HQLA1 requirements driven by balance-sheet growth (as a bank writes a loan, this creates a deposit, which needs HQLA1 held against it).

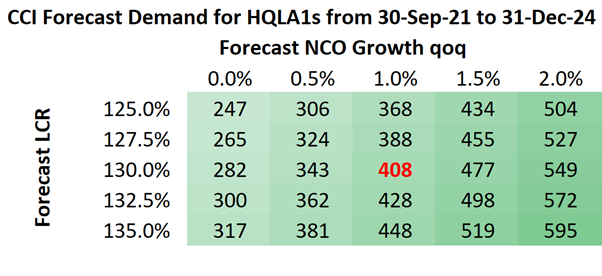

Subject to one's assumptions about NCO growth (most bank treasurers broadly assume this will track balance-sheet growth), the reasonable range for the entire banking system's HQLA1 demand is somewhere between $282 billion and $549 billion over the next 3 years. We settle on a central case estimate of $408 billion over the next 3 years. We also know that semi issuance of new bonds will probably be ~$80 billion this year, declining somewhat as budgets gradually improve over time. This is only very slightly less than the official State forecasts, which are predicated on extremely conservative budget assumptions.

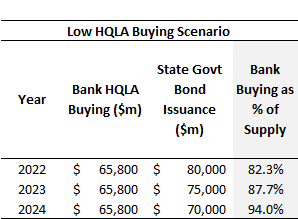

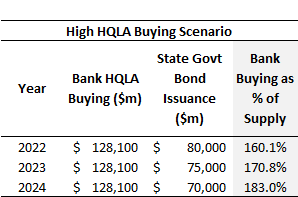

In thinking about semis demand, we exclude all other global buyers of semis, including fund managers, super funds, central banks, insurers, and other offshore investors. This analysis only focusses on bank needs in terms of HQLA1. We take our low-side scenario of $282 billion of HQLA1 needs over 3 years and juxtapose this against our high-side scenario, which is $549 billion. Applying the current 70:30 portfolio ratio, one arrives at annual buying demand ranging from $65.8 billion to $128.1 billion, which represents between 82%-94% and 160%-183% of annual semi supply.

Banks lose $140 billion of HQLA1 in 2022 through the closure of the CLF. They lose another $6 billion as bonds mature off the RBA's balance-sheet (and $56 billion through to end 2024). And then they will have to start preparing for losing further HQLA1 in 2022 and beyond as their balance-sheets grow and the TFF is repaid.

No matter how you slice and dice these numbers, the totality of bank demand is likely to be (1) significantly bigger than the RBA's QE programs as they relate to semis and (2) equal to or greater than the annual supply of semis. Of course, that is before we consider any other classes of investors.

All else being equal, this implies that semi spreads should mean-revert back to levels that have prevailed when bank buying has been a large share of annual supply.

One additional consideration here is the introduction of QE into the RBA's policy toolkit. While the RBA's yield curve targeting policy had questionable success, QE appears to have been a winner in helping keep downward pressure on long-term interest rates and the Aussie dollar.

It is reasonable to assume in future downturns/recessions, the RBA will utilise QE again, particularly as it reduces the central bank's reliance on the overnight cash rate, and hence variable-rate loans, which historically have had a tendency to blow housing bubbles. This should provide for a more balanced policy platform.

Importantly, this should reduce the maximum amplitude of the increase in semi spreads during shocks, as the RBA was able to do during 2020 when it bought semis both for market stability purposes and then via its QE program. One would think that this should ultimately generate lower semi spread volatility, and minimise maximum drawdowns.

A final consideration is NSW announcing its own QE program for 2022 and 2023, which should amount to bond buybacks worth $11 billion in NSW bonds only. We believe NSW will in time increase this to $26 billion as it draws-down on the full capacity in its Debt Retirement Fund.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $7 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 15 analysts and 8 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

3 topics