The 8 big issues for 2018

CommSec

For the past 16 years we have produced “The Big Issues” report – a report that has sought to highlight the issues that are expected to influence the economy over the forthcoming 12 months.

Now this is no crystal ball gazing exercise. The aim is not just to forecast where certain economic variables are likely to be in a year’s time. Rather the focus has been to highlight trends, issues and ‘big picture’ influences that act as threats or opportunities for consumers, investors and businesses alike.

The aim has been to produce a highly readable, relatively jargon-free document. Probably today we could call this a blog. But the intention over time has been to produce commentary that causes people to think and ask the ‘so what’ question – that is, to determine what this means for their own circumstances.

And we undertake this analysis by providing a healthy amount of graphs and pictures in addition to the text to best highlight the issues we think will prove important in 2017. Certainly one of the great innovations over recent years has been the infographic and other developments that have sought to bring subject matter ‘alive’. They say that a picture should tell a thousand words, and that should be the basis for all economic and financial commentaries – make the subject matter more alive and relevant to readers. The real value of economics is when people say ‘so what?’ and relate the commentary and forecasts to their own situation.

The Year Ahead

The Australian economy remains in good shape. Home building remains solid in most states and territories. Certainly more new homes will be finished over the next year, and this will keep investors and authorities alike focussed on the type of landing experienced: ‘hard’ or ‘soft’.

The business sector is in great shape, with conditions reportedly the best in 20 years. Businesses are spending, investing and employing and the jobless rate is gradually edging lower. The jobless rate is at 4½-year lows.

Consumer confidence is still uninspiring due to lower wage growth and greater spending on ‘grudge’ purchases like utility bills, council rates and insurance premiums. But consumers are still spending.

Federal and state governments continue to unveil infrastructure spending – especially transport. That is, roads, tunnels, railways and airports. And work on current and mooted projects will support the economy in the next few years.

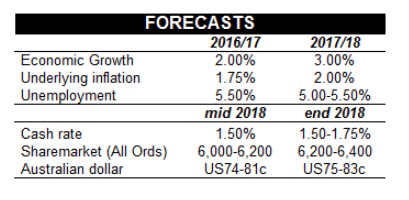

Economic growth is expected to lift from around 2 per cent to near 3 per cent over 2018. Contributions to growth are expected to be broad based with consumers, businesses, exports and governments expected to contribute to the firmer growth pace.

Inflation is expected to remain contained, resulting in stability of interest rates. Indeed the cash rate may remain at 1.50 per cent for most of the year. While we have pencilled in a rate hike for December 2018, clearly that is still some way ahead.

The Australian dollar could move either way over 2018. And much depends on what happens in the US. If the US administration is successful in legislating tax cuts, and they aren’t overtly staggered over coming years, global investment dollars may flow to the US. But at time of writing, the tax legislation still needs to pass the Senate. And then there is the question of US monetary policy if inflation stays stubbornly low.

US President Donald Trump

Year one is over. And indeed the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency has proved to be a wild ride. There have been the political appointments, resignations and sackings. There have been the foreign policy challenges as well, notably North Korea. And then there has been the economic agenda.

Some would argue that the new administration hasn’t had much of an impact on the economy over 2017. At least not yet. The tax cuts look to go ahead following the recent approval from the Senate. However the Senate and the House of Representatives need to agree on the tax bill details that will be sent to the President for signing. And a new appointment has been made to the position of chair of the Federal Reserve.

The goal of the Trump Administration is to lift the pace of economic growth to the 3-4 per cent range rather than 2-3 per cent range. And the tax cut package is seen to be one of the mechanisms that could serve to lift sustainable economic growth.

But certainly Donald Trump will claim success in trimming ‘red tape’ for small and medium-sized businesses over 2017.

And while some would contend that only a modest amount has been achieved so far by Donald Trump when compared with his stated agenda, this may not be necessarily negative. Politicians that seek to implement too many changes early in their terms can adversely impact confidence levels. And it is clear that confidence is one economic variable that has remained strong in 2017 despite the machinations involving the White House and the media.

US consumer confidence (Conference Board survey) is at 17-year highs. And a measure of small business confidence from Capital One recently hit a 5-year high.

Donald Trump can also point to an economy running at a near 3 per cent growth pace and unemployment at a 16-year low of 4.1 per cent. Whether these outcomes are driven on the absence of government influence, momentum from the 2016 year or on hope is still up for debate.

How long will inflation stay low?

Inflation has featured in our Big Issues report for a number of years. Last year we asked: “Is inflation at an inflexion point? The previous year was: ‘Will we need to worry about inflation again?’ In 2014 we posed the question ‘Is Inflation dead?’ And in the 2013 edition of Big Issues we questioned: “Inflation or Deflation?”

We have continued to find it remarkable, that with interest rates close to zero across many parts of the world and some central banks still injecting stimulus via bond buying, that the concern is still that inflation is too low, rather than it is poised to rebound.

Last year we argued that there are good reasons to think that inflation was at an inflection point. Certainly central banks maintain accommodative monetary policies. Many governments are spending more on infrastructure. Economic growth rates are lifting. The US is arguably at ‘full employment’. And a number of states and territories in Australia have jobless rates low enough to suggest that inflationary pressures may start to emerge.

In Australia, certainly construction activity is solid and prices have lifted. The annual rate of construction inflation rose from 2.4 per cent in the June quarter to 3.8 per cent in the September quarter – an 8½-year high.

But the themes of global consumer good competition and technology-driven cost cuts are still working to keep prices low. Consumers can buy goods whenever they want and wherever they are. And a combination of technology and innovation are reducing production costs. Importantly, these themes could have further to go to play out fully.

In Australia, the Reserve Bank is working on the belief that inflation has bottomed. And as a consequence, interest rates have probably bottomed. But the Reserve Bank continues to emphasise that inflation will rise only gradually. And over the next two years, underlying inflation may only have lifted to 2 per cent – at the bottom of the 2-3 per cent target band.

How long inflation stays low will certainly be debated this year. But we could continue to discuss the issue in 2019, given the track record of recent years.

The disconnect between jobs and wages

So we have been discussing low inflation for a number of years. And the trends over the past year have been especially interesting with economic growth rates lifting, while at the same time inflation has been stubbornly low.

On the basis of economic theory, that shouldn’t happen. Stronger consumer and business spending and lower unemployment rates should give businesses confidence to lift prices and thus lift margins and profitability.

But to a large extent, the theory assumes that consumer goods are sourced locally rather than globally. Goods can be sourced elsewhere in the region, state or country, but this assumes that they will be less competitive due to transport or shipping costs. And goods sourced from overseas would face even higher transactional or shipping costs.

But these transactional or shipping costs have fallen, or businesses have sought to absorb some or all these costs to access new markets. So the threat or reality of greater competition has kept inflation at bay.

The Phillips curve theory suggests there is an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. If there are fewer workers to choose from, businesses need to pay more to attract workers and, in turn, may then lift prices to recover the cost.

So there are reasons to explain why there has been stronger economic growth and stubbornly-low inflation. But what are the reasons to explain why job markets are seemingly tightening but wage growth remains low?

Some would argue that the threat of losing customers has meant that businesses can’t afford to lift pay of workers. Then other theories suggest that unemployment no longer fully explains labour market tightness. Workers may have part-time jobs but want full-time work, so spare capacity remains. So underemployment remains high. And others would say that if the pay of domestic workers lifts too high, then they could lose jobs overseas – both in goods and services sectors.

Housing: Hard or soft landing?

OK this is the third year running that this topic has been included in the year’s Big Issues. In 2015 we said: “the answer will be revealed over 2016.” In 2016 we were more circumspect saying “we believe that discussion will continue to swirl about what sort of landing the housing market will experience.”

And indeed the issue has continued to be debated. But arguably the longer that the issue is debated, the more likely that Australia’s buoyant housing markets, notably Sydney and Melbourne, will experience a soft landing.

Certainly there are many parts of the country that have far different experiences. Perth and Darwin housing markets are going through corrections after mining and energy construction booms. Adelaide and Brisbane have generally seen steady conditions. However the significant apartment building in Brisbane has led to a very soft rental market. Interestingly though, demand for some accommodation like townhouses is strong and not being met by supply, supporting prices.

The Hobart housing market is firm, benefitting from an overflow of housing demand from Sydney and Melbourne. The issue is one of under-supply rather than over-supply. And the Canberra housing market remains healthy, due in part to the control of land supply by the ACT Government.

The Sydney housing market has certainly softened with a combination of cooling demand and the gradual completion of more homes, especially apartments. The auction clearance rate has eased to around 61 per cent, down from around 80 per cent a year ago.

But population growth remains solid in Sydney and rental vacancy rates are still low. In Melbourne, the market remains solid, again supported by population growth.

A key factor that points to the potential for a “soft” landing rather than “hard” landing in markets such as Sydney and Melbourne has been the policy of lenders. Reflecting on the experience of housing over-supply in the US and Europe during the Global Financial Crisis, Australian lenders adopted a new policy. Before lenders would provide finance to developers they sought that around 100 per cent of properties be sold “off the plan” by developers. There is still scope for ‘indigestion’ in some markets with a lot of building going on, but less scope for a broader “hard landing”.

Infrastructure

Readers may feel a little more comfortable about the outlook for housing after the previous discussion. But there will always be the gloomsters. And they may contend that, while there may not be a housing market crash, once the bulk of homes are built, that will leave a gap in the economy. So no housing downturn, but perhaps a broader economy-wide slowdown.

Well one answer to that is infrastructure. Infrastructure can cover a number of areas. Social infrastructure includes buildings like hospitals and schools. Economic infrastructure includes roads, bridges, railways, airports and bridges.

Across Australia, state, territory and federal governments have announced a raft of projects in recent years. Some of those projects have already started with years of construction ahead. And some projects have only just started or are about to start.

Deloitte Access Economics says that the value of road and rail projects will lift from a trough of around $4 billion in 2015 to a peak of around $16 billion in 2020. Industry research company, Macromonitor, says spending on road, rail, harbours and bridges will peak near $35 billion in 2019/20.

In part, firmer population growth has put stress on infrastructure, causing governments to lift spending. In part, governments have been under-spending on infrastructure, so they are at the point where they have to spend money on some facilities. The federal government no doubt also acknowledges that it has a role to play in supporting the economy at a time where there are limits on monetary policy to drive momentum in the economy

While governments are spending money, much of the work has to be outsourced to the private sector. It is also important to note – unlike the mining construction boom – that the projects are spread across the nation. However, NSW, Victoria and Queensland do dominate given high population growth.

Over 2018 we expect plenty of discussion about the infrastructure projects that are underway and the impact they are exerting on business spending and employment.

The economic benefit of lower taxes

A fundamental component of US President Trump’s election campaign was the need for tax reform. So ever since his election in November 2016, US sharemarkets have been trading on the hope that the President will be successful in implementing his tax reform proposal. And indeed it is closer to reality.

Tax reform is the most important of the President's domestic policy initiatives so there is a lot riding on its success from a political standpoint.

But there also a lot riding on tax reform for the point of view of investors. Now while economists debate what sort of economic benefit is provide by tax reform – and especially lower taxes – investors have been working on the belief that there are real economic benefits.

The belief is that lower tax rates – especially for business – will serve to stimulate the economy, thus boosting business revenues and profits. And at the same time, the belief is that lower taxes will reduce business costs and again lift revenues and profits.

That is the theory. But as is always the case in economics, there are many that question whether tax cuts will provide the desired benefits.

Some economists believe that if tax cuts aren't fully funded then it will merely serve to boost the budget deficit. Proponents argue, however, that the tax cuts would be paid for by the faster pace of economic growth. That is, the increased spending, investment and employment would in itself lift budget revenues.

But still others contend that it is wrong to stimulate the economy when it is so close to full employment. If economic growth is lifted to the 3-4 per cent range then this may only serve in lifting inflation. And if the Federal Reserve responded by lifting rates and slowing down growth, then the fabled 'pay off' would fail to materialise.

Given that other governments, including Australia, may follow the US lead on tax, we are likely to hear more debate on the pros and cons of tax reform and tax reduction.

Consumer debt

Debt – more specifically household or consumer debt – is a regular topic of discussion in the media. Whether it will emerge as one of the Big Issues for 2018 is debateable.

We expect that growth of home prices will soften in 2018 with more new homes completed and coming onto the market. At the same time, the Reserve Bank Governor has indicated that the next move in interest rates is likely to be up – although in his words: “there is not a strong case for a near-term adjustment in monetary policy.” If valuations do soften and interest rates lift later in 2018, then clearly the issue of debt will work its way to the top of the agenda.

Debt can be quite emotive, so it is important to take a more clinical look at what is going on. Certainly household debt is at high levels when compared with household income. Still, it’s important to note that this is housing, rather than consumer debt. In fact the average outstanding credit card debt is near the lowest levels in a decade.

Aussie consumers have taken on more debt in part because interest rates are low, but also because home prices have risen, necessitating bigger home loans. But as the Reserve Bank points out, the level of debt may be higher but “the share of household income devoted to paying mortgage interest is lower than it has been for some time.”So the all-important servicing of the debt remains comfortable.

That doesn’t justify becoming complacent about the bigger debt load, although it also means there is no need for panic either. The approach needs to be more watchful.

If investors take delivery of their newly-completed apartments and can’t find tenants, they may look to sell. Similarly, some investors about to take delivery of their new apartments may find that valuations have softened. Again that could prompt investors to walk away from the purchase or sell. That then raises questions of what happens to home prices. If interest rates were to also rise then that would stress relatively recent buyers (mortgagees).

If consumer debt does indeed become a Big Issue in 2018, the hope is that the debate is conducted sensibly and based on broad assessments of the facts rather than emotions.

The ‘slowdown’ of the Chinese economy

Every economy that progresses from a ‘developing’ economy to the ranks of an ‘advanced’ economy experiences slower rates of key variables like production, investment and retail spending. There is a ramp up phase as the economy lifts to join the ranks of other ‘advanced’ nations then a slowdown as the economy matures.

From 2000-2013 Chinese industrial production grew at an average annual rate of 13.8 per cent. Since 2013 the growth rate has halved – averaging 6.8 per cent. Indeed, this year the growth rate has averaged just 6.6 per cent.

Interestingly, from 2000-2013 retail sales also grew at an average annual rate near 14 per cent. But since 2013, growth has eased only to 10.9 per cent, reflecting the Government’s preference for an economy to be driven by the household sector than exports or the industrial sector.

The problem with a seemingly ‘natural’ transition from growth to maturity, is that some observers misrepresent what is going on, and that can affect investor behaviour. In early 2016 the headlines read that China had experienced the slowest economic growth in 25 years. At the start of 2017, again the headlines read that Chinese growth had slipped to the slowest pace in 26 years.

In 2017 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) tips the economy to grow by 6.8 per cent, actually marginally up from 6.7 per cent in 2016. So perhaps the media will be looking for a new story to write.

The IMF expects the Chinese economy to grow by 6.5 per cent in 2018 before slowing further in coming years to grow by 5.8 per cent in 2022.

It is important to note that Japan averaged 10 per cent GDP growth from 1958-1970. In the following 13-year period it averaged growth of 4 per cent. Although it is important to note that the economy grew 6.8 per cent in 1988 and then 5.3 per cent in 1989 before growth slowed down to rates more in line with North American and European ‘advanced’ nations.

It is clearly in Australia’s interests to have a strong Chinese economy so the nation will no doubt feature as one of the Big Issues in years to come.

Rewind: The Big Issues of 2017

As we noted at the start of this report, we have been producing the Big Issues report for the past 16 years. It is interesting – and perhaps even instructive – to rewind over the past year and assess what we had on the radar screen in December 2016.

Looking ahead into 2017, we highlighted eight issues. The first issue was “President Donald Trump”. And we believe this indeed was a good choice. From North Korea to tax reform, the choice of a new Federal Reserve chair and various changes in White House appointments, President Donald Trump was very much the focus of the financial markets. And this was just year one of the President’s 4-year term. Clearly the US President will dominate again over the coming year, thus our decision to put Donald Trump back on the Big Issues list for 2018.

We also posed the question: “Inflation at an inflexion point? But rather than being at an inflexion point as most central bankers expected (or hoped for), inflation remained low across most advanced nations.

Number three on the Big Issues list for 2017 was “Fiscal versus Monetary Policy”. The good news is that many governments did indeed focus on ramping up infrastructure spending in 2017, providing support for monetary policy and serving to lift momentum for economies. Indeed Australian state and federal governments were active in announcing projects. Infrastructure spending will prove pivotal in taking over from home building in driving the Australian economy in coming years.

Housing has also dominated our ‘Big List’ for a few years. Last year we questioned:“Housing: Hard landing or soft landing?” This issue was another to make a return for 2018. While plenty of people are worried about the outlook for housing, the actual issue of the ‘landing’ has been regularly been pushed out. Of course the further the landing is pushed off into the distance, the more it looks like a ‘soft landing’ will prevail.

Another housing issue: “Housing Affordability” was on the Big Issues for 2017, and indeed it generated plenty of interest and discussion on the topic. Gradually more observers came to realise that housing affordability was an issue that tended to emerge every decade or so when home prices were on the rise. Record affordability of food, clothing, cars and home appliances means that there are still plenty of dollars to meet housing needs.

Issue 6 for 2017 was “The global political environment”. The good news is that while there were a raft of elections held in 2017, especially in Europe, the results didn’t serve to ignite fresh economic turmoil or instability on financial markets. The political environment was indeed a key issue for investors in 2017.

While we nominated “The state of the job market” as a Big Issue for 2017, the focus was largely on weak wage growth – not just in Australia, but across advanced nations. No surprise then that weak wage growth is on the Big Issue list for 2018.

China is never too far away from our consciousness. The issue we nominated as a Big Issue for 2018 was “The economic baton change in China”. This issue was very much in the Reserve Bank sights at the end of 2016. The good news is that the transition from exports and manufacturing to household spending continues smoothly.

Report with full charts

Click here for the report containing all charts

14 topics

I am married with three children (all in their 20s) and currently live in Huntleys Cove in the inner west of Sydney. Chief interest is athletics and trying to keeping up with the children.My current role is Chief Economist, Commonwealth...

Expertise

No areas of expertise

I am married with three children (all in their 20s) and currently live in Huntleys Cove in the inner west of Sydney. Chief interest is athletics and trying to keeping up with the children.My current role is Chief Economist, Commonwealth...

Expertise

No areas of expertise