The best strategy piece since the US election

Extract from: “2017– State reflation or stagflation?”

Viktor Shvets and Chetan Seth CFA

Macquarie Securities, Hong Kong

The state is emerging as an economic driver rather than just a policy facilitator. After almost a decade of experimental monetary policies, there is a palpable feeling of change in the air. Whilst no CB would dare to unwind monetary accommodation (~1/3 of GDP), monetary stimulus is now finally recognized as counterproductive. As we were anticipating for the past two years, economists are priming investors for the forthcoming fiscal stimulus. It is being dressed-up in familiar ideas of public sector multipliers and productivity improvement via public sponsored investment. The fact that there is tenuous evidence the multiplier is actually positive and that most countries no longer need infrastructure is left out (productivity is now driven by knowledge and social capital, rather than bridges).

The key question is not whether expansionary fiscal policies are on the horizon (we think this can be taken for granted), but its quantum, timing and how will it be funded. Whilst rhetoric is becoming strident, at this stage, most countries continue to operate within the confines of ‘prudent management’ that can be best characterized as a ‘drift’, rather than a significant shift. The new US administration has more aggressive plans, but it is likely fall prey to the same forces that ensure delays, inefficiencies and precludes recovery of private sector. Also, today’s world is radically different to Reagan’s. It is more interdependent (particularly finance) and globalized. It also a world that carries 3x as much leverage (hence lower capacity to absorb volatility and higher cost of capital) and unlike ‘80s it is wrecked by tectonic technological shifts. ‘80s task was to shakeoff the state. Today’s objective seems to enshrine the state as a growth driver.

Having said that, there is no doubt that eventually (in fits and starts) fiscal policies are likely to become ever more aggressive and independent of country’s debt carrying capacity, with distinction between fiscal and monetary policies disappearing and two arms merging into one potent weapon. The question is whether one needs a ‘jolt’ to the system first. Our view remains that policy makers are unlikely to embrace more radical solutions, until they have no choice and it is unclear that ’17 would bring the required ‘jolt’. We maintain that healthy reflation (rising real GDP and higher but moderate inflation) remains the least likely outcome, whilst state-driven stagflation (overheating without much real growth) is more likely. Periods of stagflation could morph into disinflation before flipping back. Neither bonds nor equities are likely to be unidirectional; nor is it certain that bond yields will be higher. In the absence of a robust merger of fiscal and monetary policies and tighter global co-ordination, it is not clear that the cost of capital can actually go up without causing disorderly volatilities.

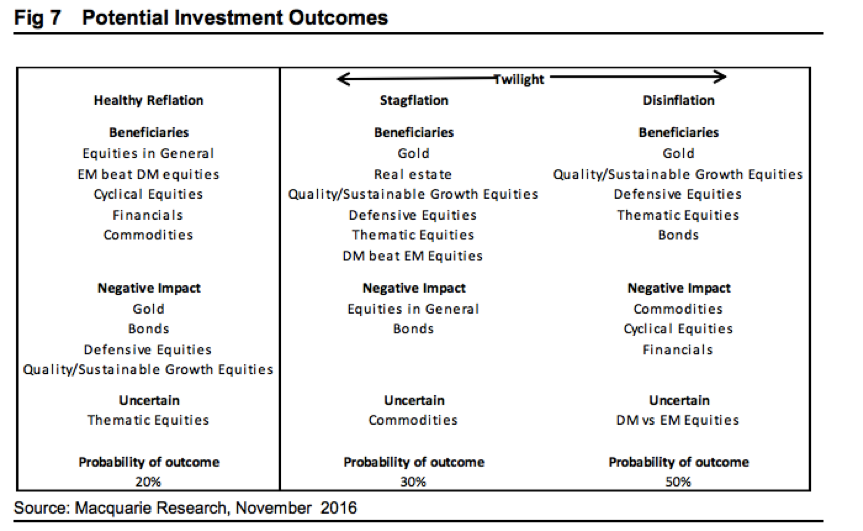

It is likely to be an important transition year. Although disappearance of CB independence; merger of fiscal and monetary policies and global coordination to avoid disruptive currency shifts are yet unlikely, investors should see the first signs of the state emerging as a driver rather than facilitator. Should we join ‘healthy reflation’ trade? In a healthy reflation (state spending leading to re-start of private sector vigour), commodities and equities (cyclicals and financials) do best, whilst gold and safety would be losers. In stagflation, gold and real estate win with poor results for equities and bonds and uncertain ones for commodities. A return of disinflation would benefit gold, ‘safety’ and growth plays. We expect ‘17 to be four seasons rolled into one. There are far too many cross-currents to second-guess risk trades. Hence we view tactical macro calls to be as risky as relying on pollsters. In this ‘fog of war’, we continue to ignore rather than embrace the state, and highlight non-mean reversionary & secular growth strategies. In terms of countries, we prefer everything local & liquid to global.

What was different about last decade vs. 1950s-80s or even 1990s?

In our view the key difference was that the private sector gradually atrophied and no longer multiplied demand at the same pace as previously. This was the reason why the public sector had no choice but to become far more aggressive.

Indeed, the genesis of the current problems can be traced back to the 1980s, when signs of declining productivity were emerging across the world, leading to stagnating incomes and rising income and wealth inequalities. Investors, who believe that we mismeasure productivity, need to explain why incomes stagnated and inequalities increased. The periods of rising productivity usually coincide with rising income and declining inequality (as it was in 1950s-70s). In our view, it was popular desire for growth and wealth creation (despite falling productivity) that led Central Banks over the last two decades towards increasingly more aggressive policies, and the same logic is now forcing the public sector to contemplate even more aggressive fiscal responses, or perhaps an outright merger of fiscal and monetary arms.

Investors are today jumping on a bandwagon of fiscally-led reflation, just as they did in 2009-11 on the bandwagon of monetary-led reflation. Hope of salvation never dies, no matter how much evidence is against it. We see four challenges with the reflationary excitement that arose following Brexit and the latest US elections.

1. The global economy is far more leveraged and financialized than it was in Ronald Reagan’s days. It is also an economy that is struggling to grow productivity and where private sector refuses to multiply demand. Unless this dynamic changes (and we consider this to be unlikely), more aggressive fiscal policies are far more likely to result in stagflation than healthy reflation. Also, unless it is globally co-ordinated, fiscal reflation could lead to disorderly currency and bond market volatilities and could easily derail a fragile and highly leveraged private economy. In our view cost of capital and US$ would remain two hard and binding constraints on the ability to do much on a fiscal side. China (as usual) is a large exception, as in China there is already no difference between fiscal and monetary policies; between monetary and banking systems and between private and public sectors. However, even China, which is already practising its own version of ‘helicopter money’, needs to be careful of how much the public sector destroys any chance of private sector recovery and how much the country is distorting its asset markets whilst creating excess capacity.

2. We view 2017 as equivalent to the period leading up to 1934 FDR’s New Deal. Hence, we are fully on-board with the idea that the entire world in five-ten years is going to look far more like China today. The emerging new world would be dominated by the public sector, which instead of trying to facilitate the private sector by offering incentives (through interest rates and spreads) aiming to change private sector behaviour, will simply give up, and become an active agenda setter and the driver of the economy. In Peter Drucker’s words (discussing a somewhat different concept in 1980s), the state would go from ensuring the right climate (i.e. avoid cold winters and exceptionally hot summers) to ensuring weather (i.e. avoiding rain or keeping temperature at a steady and comfortable 25 degrees Celsius). Whilst the private sector can be co-opted into various public projects (assuming state underwrites most of the risk), it still implies that the private sector would embark on policies that it would not by itself contemplate, if it was not induced by the public sector. The private sector is aware that in a contemporary world there is no need for incremental basic infrastructure and it also knows that the environment is changing so rapidly, that both manufacturing and trading patterns could become unrecognizable within five to ten years. Hence, apart from ensuring that biological and energy footprints shrink and that electricity and broadband demand is satisfied, in most countries, there is limited need for significant incremental infrastructure investment. The participants in labour markets also fully recognize that jobs and occupations are changing beyond recognition and that the nature of employment within five to ten years would be completely different. Hence, tax rebates or reduction in tax rates are far more likely to be saved than spent and are far more likely to be invested in creation of monopolies (to defend slipping margins) or share buybacks rather than private sector-driven non-residential fixed asset investment.

3. In order to be truly successful (for good or evil), fiscal policies need to be not just more ambitious but perhaps even more importantly, the Governments need to break the nexus between borrowing and spending. In this world, the idea of Central Bank independence needs to be junked, and the two arms of Government policy (i.e. fiscal and monetary) need to be merged. We call it nationalization of credit but other investors prefer to describe it in less precise terms as ‘helicopter money’. This would create an exceptionally powerful (and dangerous) instrument that would have almost no limitation imposed on it. It can take many forms, such as fiscal authorities depositing zero coupon, non-redeemable and non-refundable bonds (either government or infrastructure); or it could involve Central Banks directly writing a cheque; or it could take the form of Central Banks guaranteeing maximum cost of capital (such as the Fed’s policy in 1940s-early 1950s, when the Government bond yields were capped at 2.5%). Any of these policies basically break the nexus between borrowing and spending, and could open ‘floodgates’ of both productive and unproductive spending. As discussed in our prior notes, we think that creating minimum income guarantees is an inevitable longer-term outcome of disintegration of conventional labour markets as well as declining importance of labour inputs. We similarly think that increased state spending and support for R&D (particularly R) and skills training could be very useful. In some cases (like Japan or Eurozone), we don’t see an alternative to underwriting or nationalizing financial super structure. However, fixed asset and infrastructure spending are likely to be grossly distorting and unproductive (even in most EMs, bar least developed like South Asia or Africa).

4. However, to accept expansion of fiscal and investment policies, without any discipline imposed by the market (bonds and currencies in particular) is a giant step into unknown (or more precisely its extreme negatives are exceptionally well-known, ultimately leading to either hyperinflation or stagflation or devastating deflation). Hence, we maintain that the next step requires some form of a ‘jolt’ to the system (arising more than likely from US$600 trillion+ ‘cloud’ of financial instruments), forcing politicians and bureaucrats to coalesce around such aggressive policies. We also agree with the IMF that in order to avoid disorderly re-pricing of risks in various asset classes, there is a need for globally co-ordinated policies. This would preclude policies designed (say) for the US, suddenly causing collapse of the EM demand and compression of global liquidity. However, as in the case of the merger of fiscal and monetary policies, it is hard to imagine such co-ordination, unless there is no other alternative.

We therefore believe that investors are currently jumping the gun and trying to rapidly reposition their portfolios in expectation of a quick and robust change in public policies. As discussed in sections below, we do not currently see much more than a ‘drift’ in fiscal policies. It would take a far greater ‘jolt’ to the system, to allow for various Governments to not only break-out from the straightjacket of perceived limits to ‘debt-carrying capacity’ but to start behaving truly irresponsibly. In the short-to-medium term, we think that the answer is likely to be a drift upwards in fiscal deficits but of insufficient strength to offset monetary policy abeyance. As always, the devil will be in the detail, and we suspect all of the new spending announcements would fall prey to hesitancy, delays, and negotiations and would be ultimately judged unproductive. The only areas where the Governments will act aggressively are actually the deflationary or stagflationary areas of trade and immigration. We are likely to see rapid expulsions, greater closure of borders and more aggressive strategies in using local taxation and licensing laws, slapping anti-dumping duties and ending free trade negotiations. These are easy wins to placate the ‘base’ (whether in the UK, Eurozone or the US or indeed EMs) whilst working through more complex issues.

The new world would ultimately emerge, but its birth is likely to be far longer and far more protracted. In the meantime, we believe that investors are residing in a ‘twilight’ zone, between death of monetary policy activism (largely ended with QE3 in late 2014) and the arrival of a new world. In the twilight zone, disinflationary pressures remain strong, and Governments would need to fight to reflate individual economies. Investors would continue to gyrate between stagflation and disinflation, with ‘healthy reflation’ being the least likely outcome. Essentially, the challenges have not changed and solutions remain incomplete.

What are the investment implications?

If we assume that ‘Twilight’ is the most likely outcome, then it is difficult to make categorical judgements (such as “the 30-year bull market in bonds is over”). Instead, investors are likely witness cross-flow of decisions and news, some strongly disinflationary, some inflationary and quite a lot falling into the category of stagflationary. In our view this implies that investment styles either have to be incredibly flexible to accommodate various phases with a great deal of dexterity or alternatively, investors could attempt to maintain a steady course by assuming continuation of non-mean reversionary world that prevailed over the previous five years.

To put it another way, either investors have to become ‘political economists’ or extremely fast followers of the policy direction that appears to be winning. The fast following trend settings are suited to computer intelligence and some quants. However, conventional investors are running the danger of being whiplashed, as neither their skill base nor the nature of their mandates can easily accommodate either the political economy or fast trend following.

We tend to call these strategies, the ‘Follow the Government’ approach. However there are also set of strategies that attempt to ignore the Government. This had been our preferred choice over the last five years. We have deployed two strategies that attempt to ‘ignore the Government’: (a) ‘Thematics’ (declining return on humans and capital’) and (b) ‘Quality Sustainable growth’ (companies that can maintain high ROE, primarily through margins and without excessive leveraging). Both strategies largely ignore valuation multiples and assume non-mean reversionary world of deep secular shifts and a mix of stagflation and deflation. As can be seen below, both are prime strategies for a dislocated world but would not do as well in ‘healthy reflation’. Currently, we place ~15%-20% probability on such a happy outcome.

The same principle applies to our country allocations.

If there is a trend towards ‘Healthy reflation’, it would be trading nations (in particular commodity producers) and countries with limited domestic liquidity, and thus reliant on reflation of global demand and liquidity flows that would do the best (for example Indonesia). However, in a twilight, we prefer countries that have a large domestic base (i.e. China, India, Philippines); countries that have significant in-build domestic liquidity and low external vulnerability (i.e. China, India, Philippines, Taiwan) and countries that have the capacity to deliver non-cyclically or commodity driven productivity growth rates (i.e. India and the Philippines). We also prefer countries that have already suffered from a fairly large damage from declining terms of trade (i.e. India, China, Philippines, Taiwan and Korea) rather than betting on further significant gains in terms of trade (i.e. Indonesia or Malaysia).

Whilst recognizing that no country is perfect (for example India could easily suffer from greater than expected deterioration in macroeconomic outcomes as a result of monetary consolidation), we maintain largest overweights in India, China, Philippines and Taiwan.

6 topics

Alex happily served as Livewire's Content Director for the last four years, using a decade of industry experience to deliver the most valuable, and readable, market insights to all Australian investors.

Expertise

Alex happily served as Livewire's Content Director for the last four years, using a decade of industry experience to deliver the most valuable, and readable, market insights to all Australian investors.