The bigger (the multiple), the harder they fall

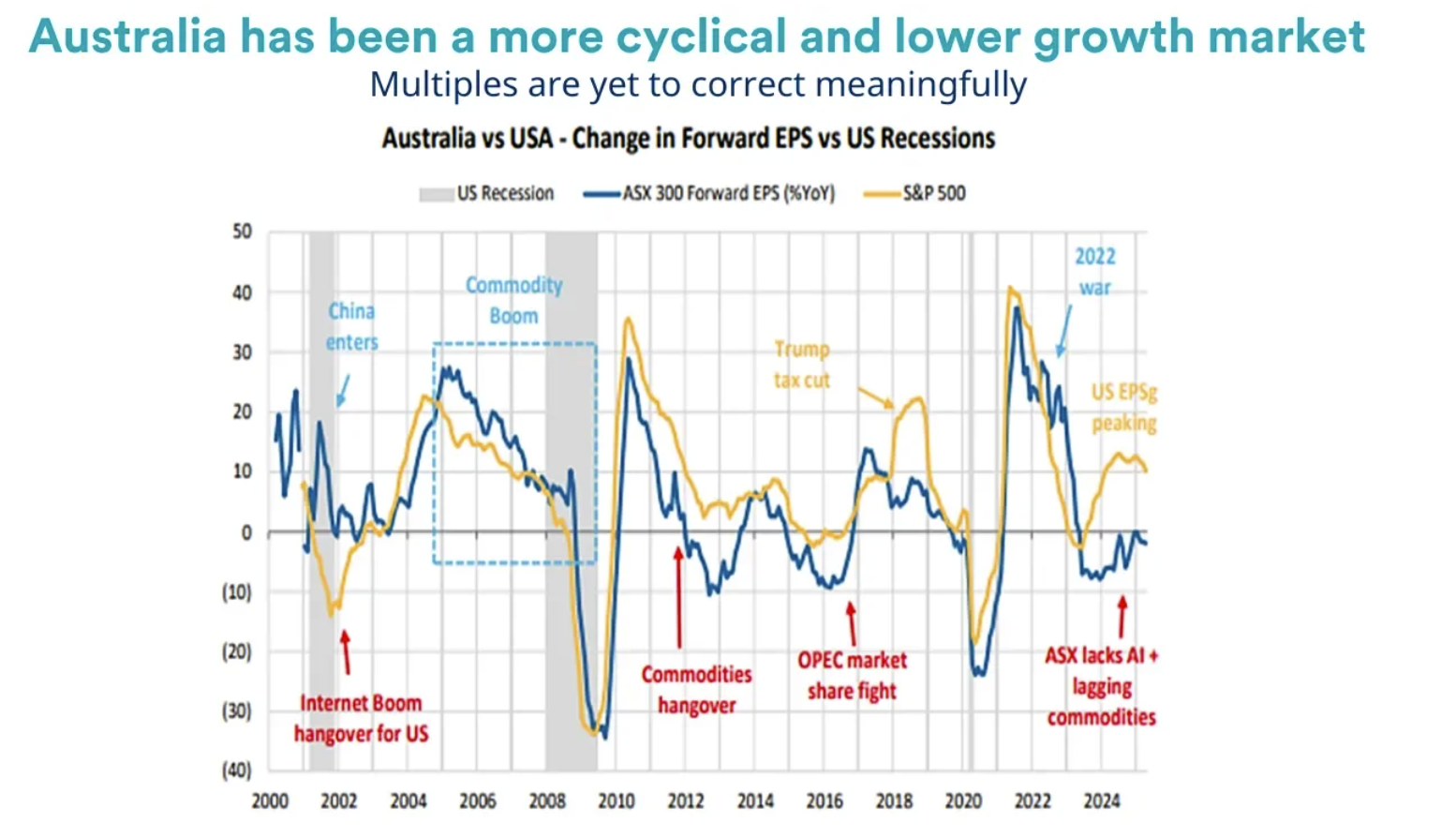

Market prices for assets of most types, and certainly most companies on the ASX, have had a golden generation. Prices have been fueled by growth in earnings and cashflows, but far more by multiples increasing across the board but especially for those promising growth. In turn, many of the economic orthodoxies introduced since the early 1980’s, all pivoting from a belief that free markets and relative comparative advantage are best for societies and economies, have been, at best, challenged.

Those orthodoxies were built upon a trinity of beliefs – independent monetary policy, driven by central banks with a primary mandate of targeting inflation; prudent fiscal policy; and trade policy which encouraged an efficient allocation of resources and hence optimizing global growth by reducing tariffs and ensuring comparative advantage is able to be fully expressed through global trade.

In recent years, for different reasons, monetary policy has been hijacked and used for purposes other than price stability, long after the GFC “emergency” which prompted this first break. Ray Dalio (“How Countries Go Broke: Principles for Navigating the Big Debt Cycle, Where We Are Headed, and What We Should Do”) and others have warned that fiscal deficits had reached unsustainable levels and needed to be quickly and sharply reduced. Trade policy was (relatively) the last standing preserve of the three orthodoxies in the developed world. Until Liberation Day.

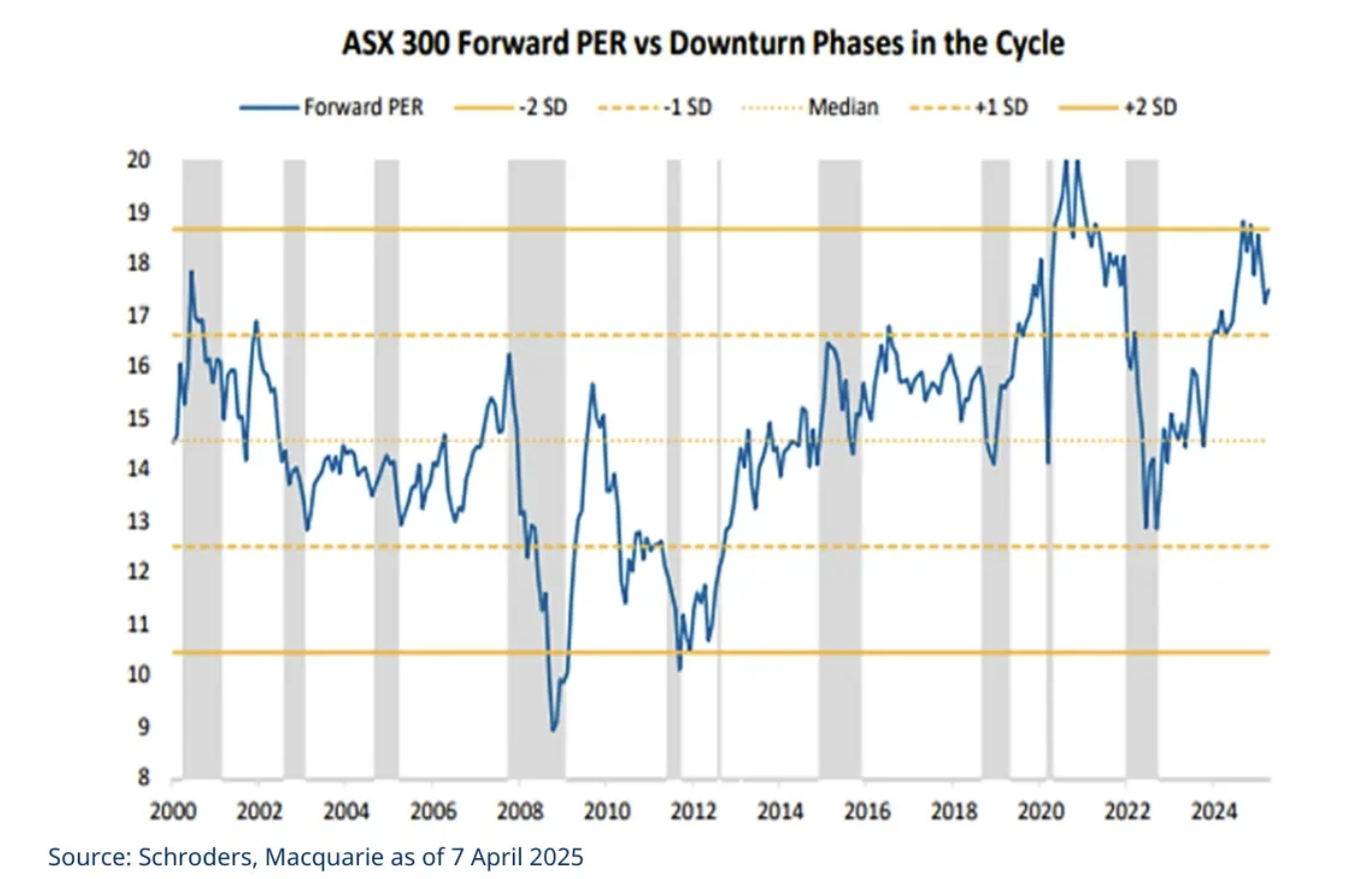

With Liberation Day has come yet another challenge to that golden run for asset prices. The fact that we have seen 20%+ declines in market prices in 2011, and 2016 and in 2018, putting aside the extreme volatility seen during the covid travails of 2020, is easily forgotten when those declines are subsequently more than recaptured. And it is tempting to think that this market sell off will mimic those experiences and that a “rescue” will emerge; history often rhymes. None of that, though, is to be confused with fundamental value for the market, which from first principles we estimate to be fair at 14 times earnings before interest and tax for the Australian equity market as a whole. Expressed another way, a pre tax, pre interest earnings yield of 7% (representing a long run risk free rate assumption of circa 3% and a risk premium net of real growth of circa 4%). For completeness, these are cashflow numbers and is not unusual for reported profits (especially underlying profits) to be higher than reported cashflows, especially for highly acquisitive companies or those with complex accounting (such as high accrual levels of long dated actuarial assumptions). With higher risk free rates (bonds remain stubbornly closer to 4%) and stagflationary pressures weighing on growth outlooks even after three years of no earnings growth for the ASX, the risk is that this fundamental value marker for the market is generous rather than onerous, even though the market has rarely traded at that level through recent years.

We have consistently expressed the view that fundamental value has been scarce across the ASX as a market for some years.

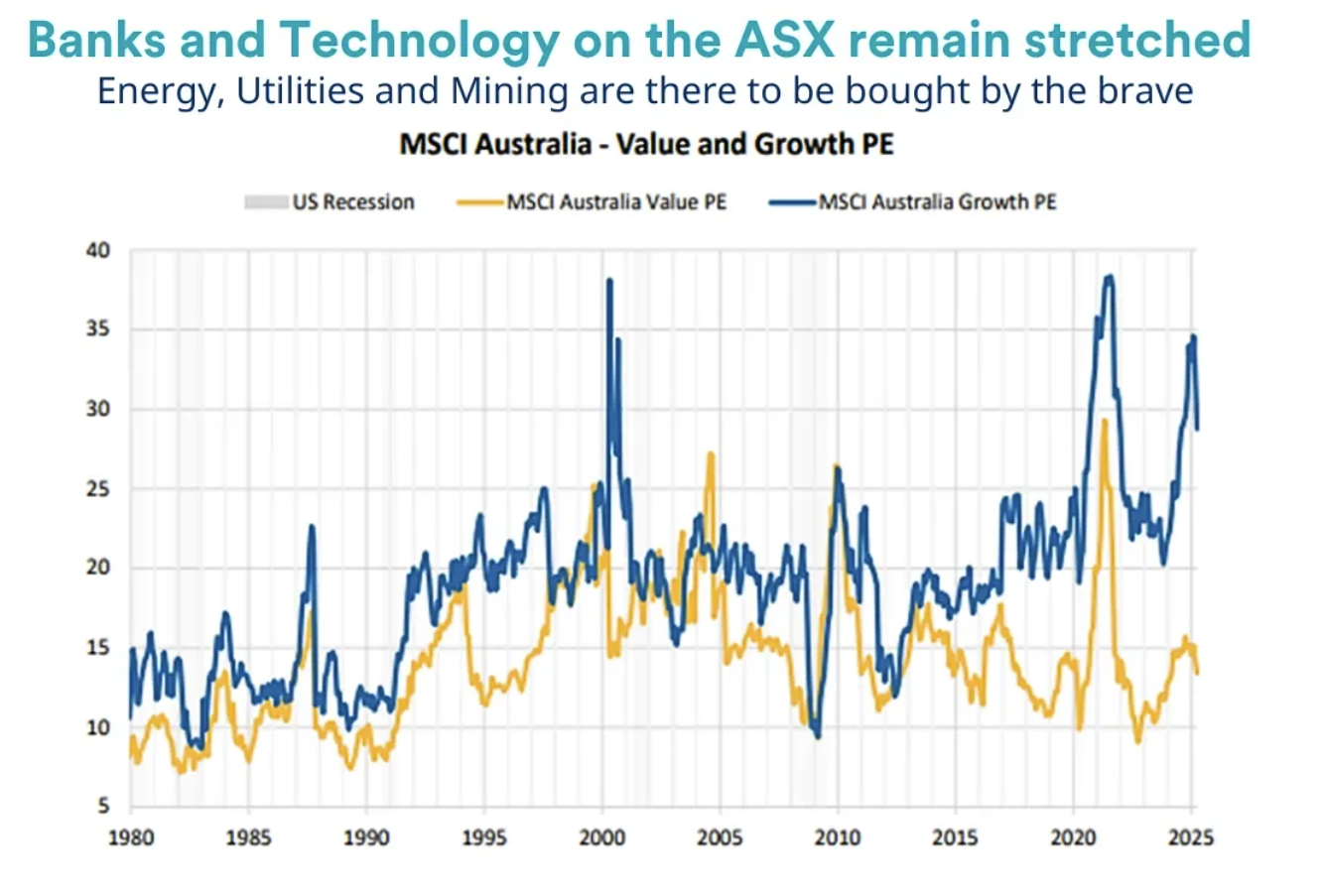

The temptation to think that a market correction automatically prompts a buying opportunity is more attractive to us when we are able to buy sustainable earnings streams at this multiple level, or ideally lower. Whilst that always presents itself across the whole market in certain stocks or sectors, it certainly hasn’t yet across the market as a whole, and the extreme bifurcation between those companies labelled growth stocks and those labelled value stocks on the ASX has narrowed, albeit from an extremely stretched base such that it still has some way to correct before an equilibrium multiple spread between the two is observable.

Put another way, the market reaction to the imposition of tariffs has only occurred to the extent it has, because of the fragility of the value underpinning for the market. Companies trading on lower multiples with strong cashflows relative to reported earnings and less financial and operational gearing have been less effected by the market retracement od recent months. And ultimately, for an investor, they are the four critical elements for a “defensive” share – it’s not just that earnings and cashflows are robust, and also that the balance sheet is prudent but crucially, that the multiple is fair. Some good companies that meet the first three criteria have underperformed aggressively in this correction, simply because their starting multiple was so stretched, which in turn was the basis for the rapid ascent in their market value through recent years.

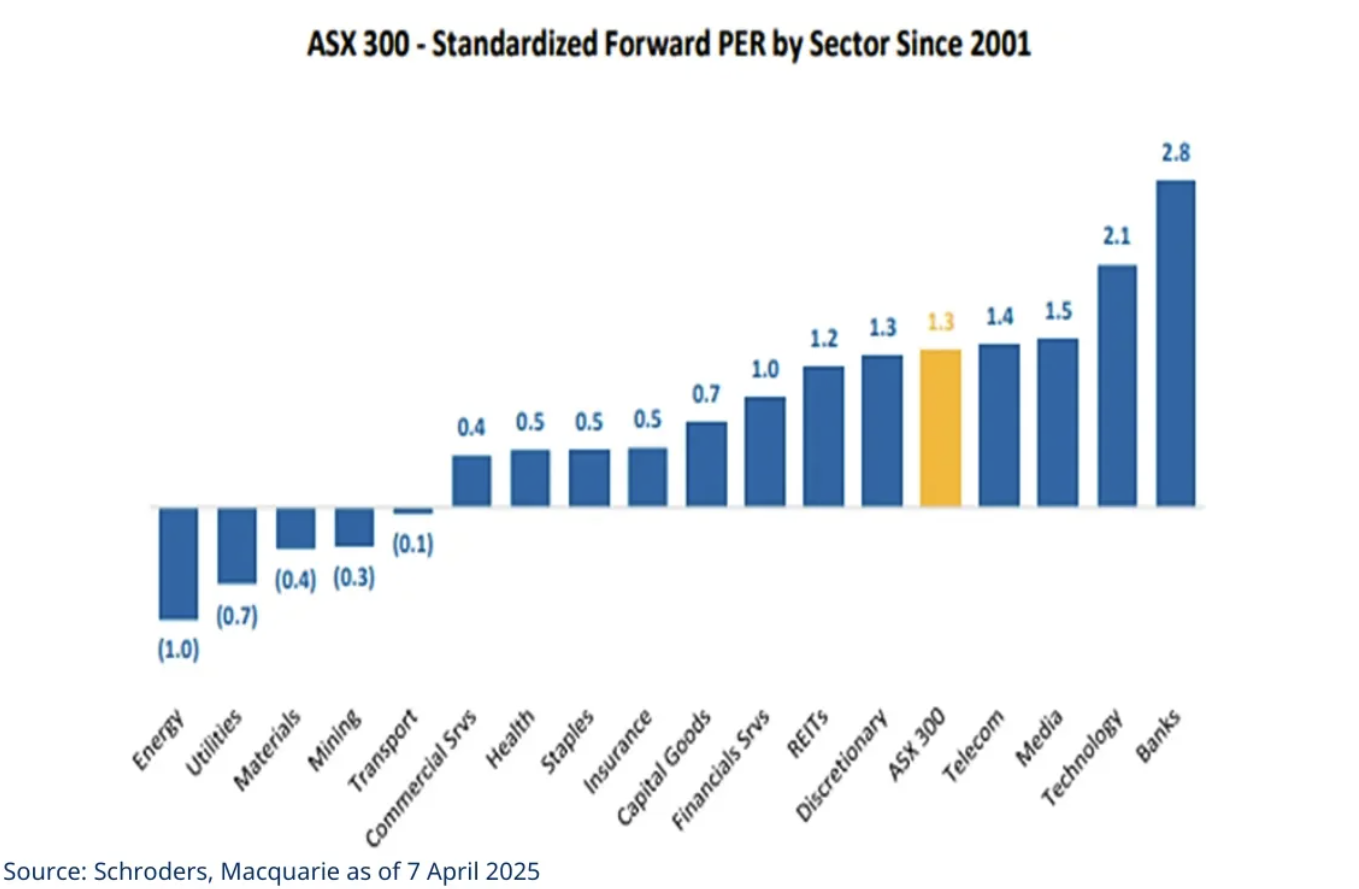

It can be seen in the chart below that the rapid rerating of the market in the past couple of years has only modestly unwound and, in the face of the third year of no earnings growth for the ASX, and with a market that is still overearning relative to its sustainable earnings, a material further correction is required for assets to approach the fair value market we quantified above.

Within the market, even after the correction, the growth and market darlings continue to trade well above historic norms and multiples their fundamentals would suggest. The extreme outlier remains the banking sector, which enjoyed a stellar year in market return last year even as underlying earnings fell across the sector. As the CEO of a major bank said to us during recent months, ASX bank multiples now assume bad debts never infect the mortgage books. This is possible, but unlikely without significant government intervention of one type or another. It is of course also the case in many other global banking systems and yet they do not trade on the multiples enjoyed by the Australian sector, and CBA (ASX: CBA) and Macquarie (ASX: MQG) in particular. To date, in many countries in the world there has been a social tax on banks in exchange for this tacit state support, whereas in Australia many sectors, especially supermarkets but also insurance, are attracting government ire before the banks are mentioned. ANZ (ASX: ANZ) of course have done their best to provoke a reaction, with a Board that’s doing an ASX impersonation of Baghdad Bob, and yet even then the sector hasn’t yet attracted political opprobrium and economic censure. We continue to be underweight the banks and especially the highest multiple banks, and would be concerned that this call may be an undue risk if operating cost growth was to be reduced to levels below revenue growth, ideally in a sustainable way. There is no guidance to that end currently, nor prospect of it occurring in the normal course given the current operating plans for each of the listed retail banks.

The chart also highlights how the market as a whole continues to trade at multiples well above longer run trends, with the TMT sectors joining the banks with higher multiples still prevailing after the recent correction. In contrast, energy, utilities (especially Origin (ASX: ORG)) and materials and mining are the sectors trading well below trend.

It is easy to make the case that macro trends support these positions; after all, “Drill Baby, Drill” is not likely to presage oil price strength. And playing bluff with PoTUS hasn’t helped market returns in recent weeks. Consequently, for energy to be a long last on this list may be warranted. Our only retort to that would be that companies can sometimes overwhelm these macro factors with intent and action, especially with respect to reducing OPEX and capex spend such that cashflows are optimised. This is what has seen Boral (ASX: BLD) perform so well in recent years despite reducing concrete volumes; and Santos is an example of a company where after a period of high capex the next few years offers the prospect of stronger free cashflow, even at lower energy prices. Our long run oil price assumption continues to be below spot, reflecting cost curves, as remains the case with many commodities, and especially iron ore and copper. Lithium, Alumina and Aluminium are the exceptions, where spot commodity prices are below our long run assumption and cost curve support, and again our portfolio remains positioned accordingly.

It would be remiss of us to finish this commentary without reference to James Hardie’s (ASX: JHX) acquisition of AZEK for US$8.8b, in cash (slightly less than half) and scrip. We have held a position in Hardie for many years, albeit we have reduced the position in recent years reflecting the concern with management we expressed in this commentary published late last year:

“… If Alan Joyce was the high priest advocate of running a business for the short run, those legitimately doing to the contrary must often be frustrated by the lack of recognition they receive for this long term perspective. An example of a change in philosophy in this regard is James Hardie, where in recent years and due to a cacophony of unrelated circumstances, much institutional memory has been wiped from the board and management (who had very much run the business with a long term and shareholder value perspective). A new chair, CEO, CFO and now head of IR, each with a US base and mindset, has led to a different strategy and risk profile. … Hardie has released the pricing lever in the past three years, lifting price more in that time than had been the case for the past decade. A margin frenzy has been the obvious reaction, with the “beats” provoking the predictable market response. As shareholders in Hardie, long may it last. However, we are not blind to some of the potential cost of this strategy. A former, long standing and highly successful CEO of Hardie, once asked us to hold him to account were he ever to allow margins to reach levels much lower than have been recorded in the past two years for the very reason that it would jeopardise the potential terminal penetration of fibre cement as a product in the US market, which was, and is, the major value driver for the group. Interestingly, for the first time on record, the US Census recorded fibre cement as losing share in completed single family houses in the US in 2023 (23% to 22%). It is of course true, as Hardie management now maintains, that the group’s margins and returns are so high that allowing laxness in OPEX and CAPEX does not now matter too much; but that does little to acknowledge that it is only an asset that can be exploited because of the eternal vigilance on both fronts by those that preceded them. The long term benefit of a disciplined operating cost base, and capital expenditure, can easily be underestimated. Without such recognition and care, such an asset can readily be diluted or worse. …”.

It is fair to say that the Hardie management did not take kindly to these comments, which surprised us as we felt them largely factual. Certainly nothing has transpired in the subsequent eight months for us to regret any of the expressed concerns. The endowment left for the current Hardies board and management was an invested capital base (largely organic) of circa US$4b, with US$1b of debt and an earnings before interest and tax of circa US$900m. In that context, spending US$8.8b to buy a business that until last year had made US$130m in EBIT for some years, with some curious adjustments seeing that increase last year to US$230m and forecast to rise to US$400m in two years. If those forecasts transpire, along with the claimed synergies (US$125m in cost synergies on a cost base of US$1.2b last year; and a further US$500m in “commercial synergies”), this will be a fair deal. We feel that about as likely as my learned colleague Mr Conlon beating Gout Gout in their next race (over any distance). What is far more likely is that the US$230m in EBIT produced for AZEK last year is a (very) good level of profitability for it to hold, which even allowing for the cost synergies to be realised implies a multiple at the US$8.8b purchase price somewhat higher than the fair value multiple of 14 times for the market, we spoke to earlier in this commentary. We suspect the Hardie board and management care little about shareholder value diminution, which is why no JHX shareholder vote is occurring notwithstanding a 35% increase in shares on issue. They simply channelled their inner Leslie Chow from The Hangover, saying “Toodaloo” to ASX shareholders as they closed their tinted windows and returned to the US.

Market outlook

The Russian saying “The past is more unpredictable than the future” has never felt more apposite. It is of course true that a tariff war hasn’t been seen for many decades; but nor had monetary policy been as aggressively used as has become commonplace before 15 years ago; and nor has fiscal deficits and debt levels reached current levels without any intent to reduce the for decades either. And yet the world economies and markets, and the ASX, prospered nonetheless. That’s not to trivialise the current risks; we would much prefer independent monetary policy, prudent fiscal policy and zero tariffs. But, alas, we are way past that point, and we don’t believe in the face of this that increasing tariffs are the only risks confronting investors; or even the major risk for equity investors in the face of still stretched multiples. Our portfolio has performed relatively better in recent months as market conditions have started to normalise, and all the tariff announcements have done thus far in our mind is highlight how stretched equity multiples had become. Indeed, bond yield movements have been relatively muted relative to equity volatility, which underscores the extent to which the ASX investor reaction to Liberation Day reflected unduly high starting multiples at least as much as it does concerns over tariff changes. Consequently, our portfolio remains more focused upon capital preservation than capital appreciation, with bias to longer duration, strongly capitalised and cashflow generative businesses which not only reflects these characteristics but are also trading at fair multiples.

The introduction of tariffs by the current US government has created an evolving set of dynamics which we are closely monitoring. All performance numbers mentioned are accurate and comments made were reflective of our opinions as at 31st March, 2025.

Learn more about investing in Schroders' Australian Equities.

6 stocks mentioned