The economics of aging

The following is an extract from a note that was recently sent to investors in the Montaka Global Fund. There is a significant change in demographics that is currently taking place in many regions of the world. The world is aging. Whether in the United States, Australia, Western Europe, China or Japan: populations are getting older at an accelerating rate.

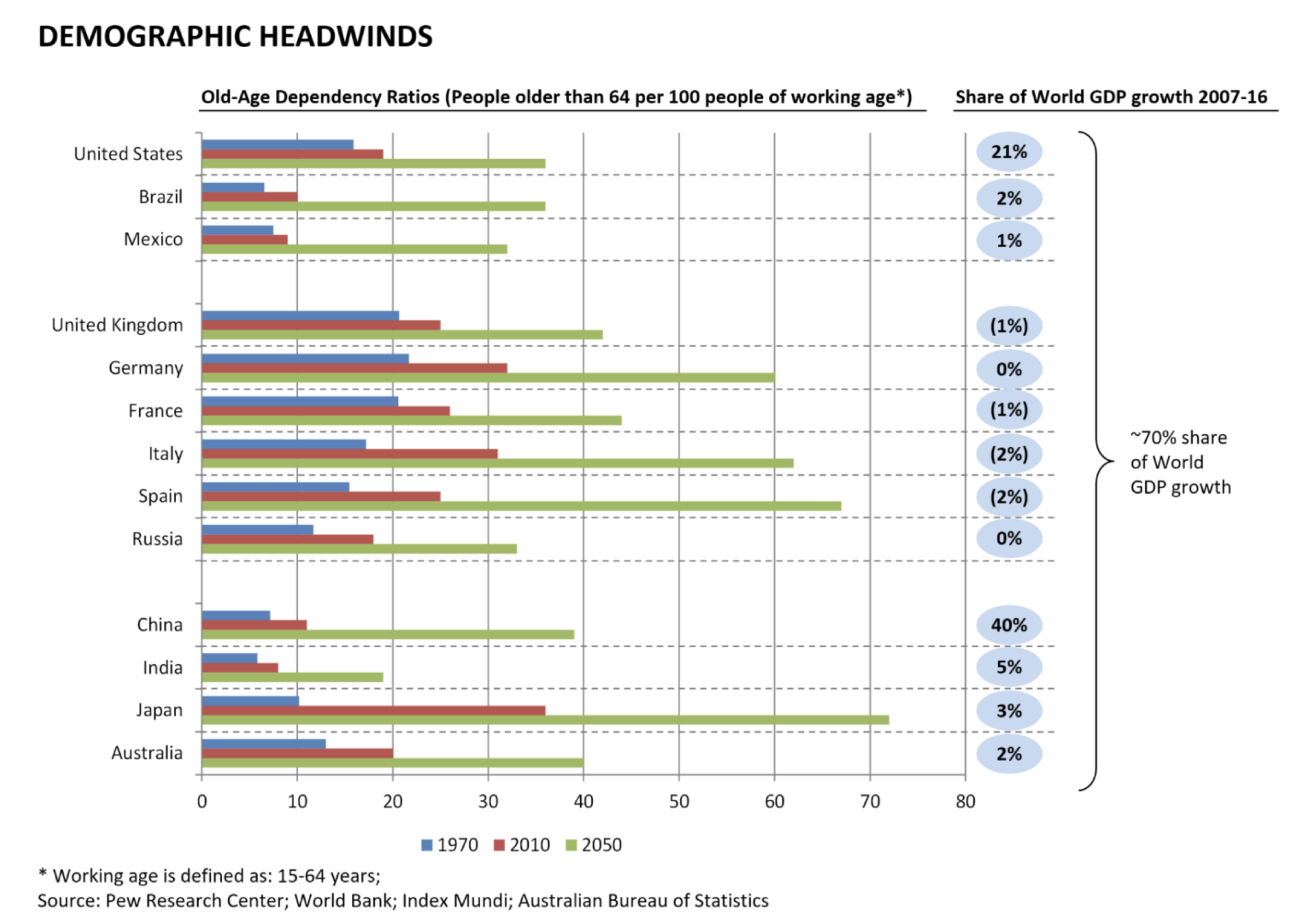

The chart below has long been a favourite of ours to illustrate this dynamic visually. The colourful bars show the old-age dependency ratios for each country in 1970 (blue), 2010 (red) and 2050 (green). The old-age dependency ratio is defined as the ratio of people older than 64 per 100 people of working age (15-64 years old). The higher the old-age dependency ratio, the more aged the populations has become.

Of course, what really stands out from the chart above is how these old-age dependency ratios really accelerate over the coming 30 years. And from these countries alone, we calculate around 70 percent of global economic growth over the last decade has been sourced. So this really is a globally significant trend.

The consequences of this demographic trend must be considered by investors. Like with all future events, we try to think less about what is going to happen (a deterministic approach) and more about what could happen (a probabilistic approach).

To assist us in our ongoing quest to uncover the range of possible outcomes stemming from the above dynamic, we found a recent paper published by the European Central Bank to be quite helpful: The economic impact of population ageing and pension reforms.

Now, the Europeans – like much of the western world – have large incentive to try to understand the consequences of demographics. As the paper notes in its opening paragraph:

“According to Eurostat’s latest projections, population ageing is set to continue and even intensify in the euro area over the next few decades. This ongoing process, which stems from increases in life expectancy and low fertility rates, is widely expected to lead to a decline in the labour supply and productivity losses, as well as behavioural changes, and is likely to have an adverse effect on potential growth.”

The paper then goes on to make a number of interesting predictions along a number of key economic dimensions, which can be summarised as follows:

Private savings

“In the euro area, the expected increase in the number of pensioners as a percentage of the total population between now and 2070 implies a shift from savers to dissavers, which suggests that this will have a downward impact on aggregate savings in the long run. Over the next ten years, however, this effect on savings might not be visible as a result of the sizeable baby boomer generation becoming elderly workers. Since this age group is the one with the highest savings rate, per capita savings are likely to increase in the short term… As life expectancy increases, households may save more during their working lives, anticipating that those savings will have to see them through a longer period in retirement.”

Productivity

“Several studies have found significant negative effects on aggregate labour productivity as a result of an ageing workforce… This may be explained by the hump-shaped distribution of average productivity across cohorts that has been found by some studies, which may be related to a slowdown in the adoption of the latest technology as age increases (with statistics showing, for example, a reduction in workers’ participation in training with increasing age) or a deterioration in the health of some older workers.”

Public Budgets

“Higher age-related primary deficits are expected to contribute to higher government debt-to-GDP ratios. Converting the projected additional age-related spending into a net present value provides an indication of the implicit liability that is caused by ageing and the fiscal adjustment that is needed in order to fulfil the intertemporal adjustment constraint.”

Economic Growth

The paper publishes the results of an ageing shock on a hypothetical economy using dynamic general equilibrium modelling. Following the aging shock:

“The ratio of workers to pensioners declines. As comparatively fewer people are in work, the labour supply and employment decline. Moreover, private consumption per capita also declines, as workers in particular reduce their consumption. Instead, workers increase their precautionary savings by investing in government bonds, in order to smooth their consumption over a longer period in retirement. Pensioners dissave more gradually in view of their rising life expectancy. Private investment declines only marginally. Overall, the ageing shock results in GDP per capita declining… The real interest rate falls as the ratio of capital to labour increases on account of the shortage of labour supply. Total pension costs rise owing to an increase in the number of pensioners, while revenue from VAT declines on account of a fall in consumption.”

* * *

While this is a lot to digest, it does start to paint a picture of the various economic forces that will likely result from aging populations around the world. It points to headwinds on economic growth due to reduced consumption – which in turn, would logically lead to reduced investment. Interestingly, higher savings would logically keep interest rates depressed – good news for heavily indebted households and governments all around the world. And on public debt-sustainability? While public budgets deficits will likely expand, they may (just) be sustainable thanks to the low interest rates caused by the low growth environment and higher rates of savings.

And implications for equity markets? Well, low economic growth translates into low growth in sales and earnings for corporates. This is, of course, a negative. On the positive side, to the extent global interest rates remain subdued, then valuation multiples may not contract as they might under a rising rate environment. (This is more the absence of a negative than a new incremental positive). All of this says that, on a multi-decade time horizon, average future equity returns will likely be lower than they have been in the past.

And while this blog is highlighting a demographics problem the world will face tomorrow, it is important for investors to consider this issue today. Equity markets price businesses according to today’s expectations of the future. The equity market does not wait for the future to happen before it reflects its impact in today’s prices. As the consequences of global demographics become more fully appreciated by investors over time, this will increasingly be reflected in global equity prices – perhaps, in the not too distant future.

3 topics

1 stock mentioned