The Fed abandons interest rate guidance: What's next?

Markets knew the Federal Reserve was not going to move the dial on interest rates yesterday. What they were hoping for was more guidance on when interest rates would start to move down. Instead, Fed Chair Jerome Powell decided to give them something akin to a double slap.

First, in the actual decision statement itself:

"The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%."

Then in the press conference that followed:

"Based on the meeting today, I would tell you that I don't think it's likely the committee will reach a level of confidence by the time of the March meeting to identify March as the time to do that. But that's to be seen," Powell said.

At least they have finally admitted what the market has known for some time - the policy rate is at the peak for this cycle.

In this wire, I'll analyse the Federal Reserve's latest decision - and more importantly, what comes next.

Trying to avoid a second mistake

“The Fed was badly burned in late 2021 and 2022 when they thought high inflation would be transitory, then got caught by surprise when it was higher and more persistent than expected. They want to avoid making the same mistake twice,” Bill Adams, chief economist at Comerica Bank wrote today.

To avoid making this second mistake, the Federal Reserve needs two things to be confirmed before it can cut rates.

1) The disinflation trend must be ultra-clear: The Fed's inflation goal is not 2-3% like it is in Australia: it is a much more concrete and firm goal of 2%. Last year, some market participants (namely PIMCO in its 2023 secular outlook) argued that central banks may cut rates even if inflation does not hit 2% exactly.

"We don’t expect developed market central banks to formally change their targets, but do expect those targeting 2% to be willing to tolerate “2-point-something” inflation as part of an “opportunistic disinflation” strategy," PIMCO wrote in June 2023.

But if Powell's comments are any guide, they aren't letting go until they hit 2% exactly.

"We have growing confidence in the inflation data but we have to get it right," Powell said on Thursday, adding that, "We won't keep it a secret when we have confidence on inflation."

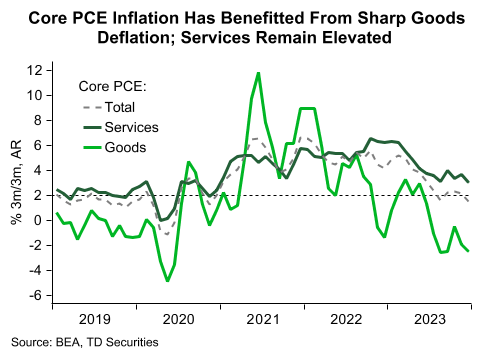

2) A confirmed fall in services inflation fall and for goods inflation to not rise again: The US has, in some ways, the same problem as Australia in that goods deflation is notable and is coming through with some element of consistency. Unfortunately, services (or what we call, non-tradables) inflation is not at the 2% level it needs to be.

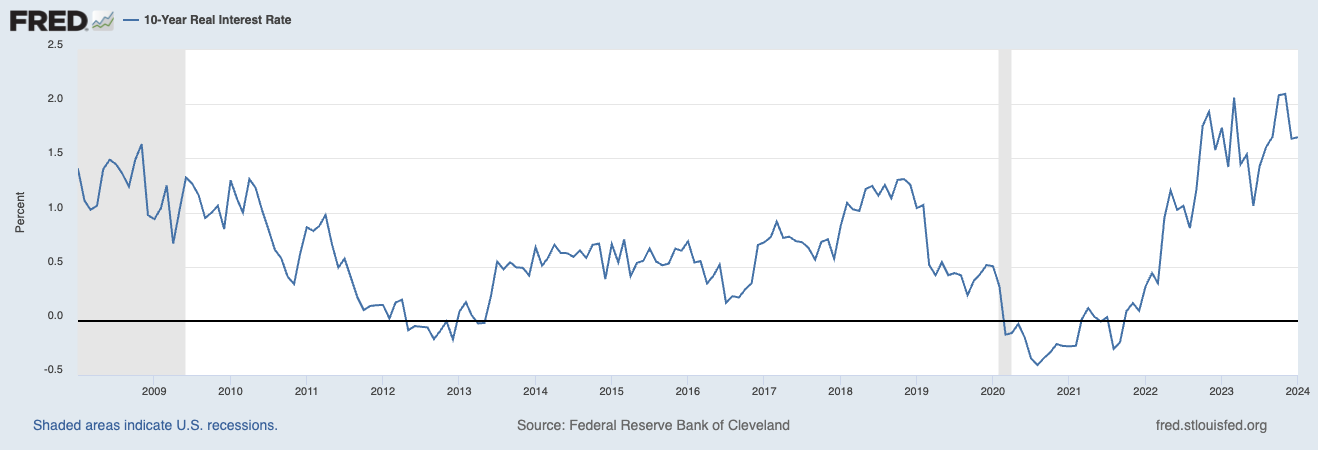

Finally, as I've alluded to in the past, central banks also use the real rate to identify when it's time to cut or raise nominal interest rates.

The US real interest rate is just over +1% - meaning the nominal interest rate is higher than inflation and the Fed technically has room (albeit, not much) to cut rates. But it also knows that cutting rates may spark another consumption and inflation spike - just when it thought it had snatched victory from the jaws of defeat.

.png)

What's next

The Federal Reserve will conclude its next policy meeting on 20 March (ironically, one day after the Reserve Bank of Australia's March meeting). The first indication of whether the Fed will have its decision vindicated will actually come tomorrow evening (Friday 2 February) when the latest jobs report hits the wires.

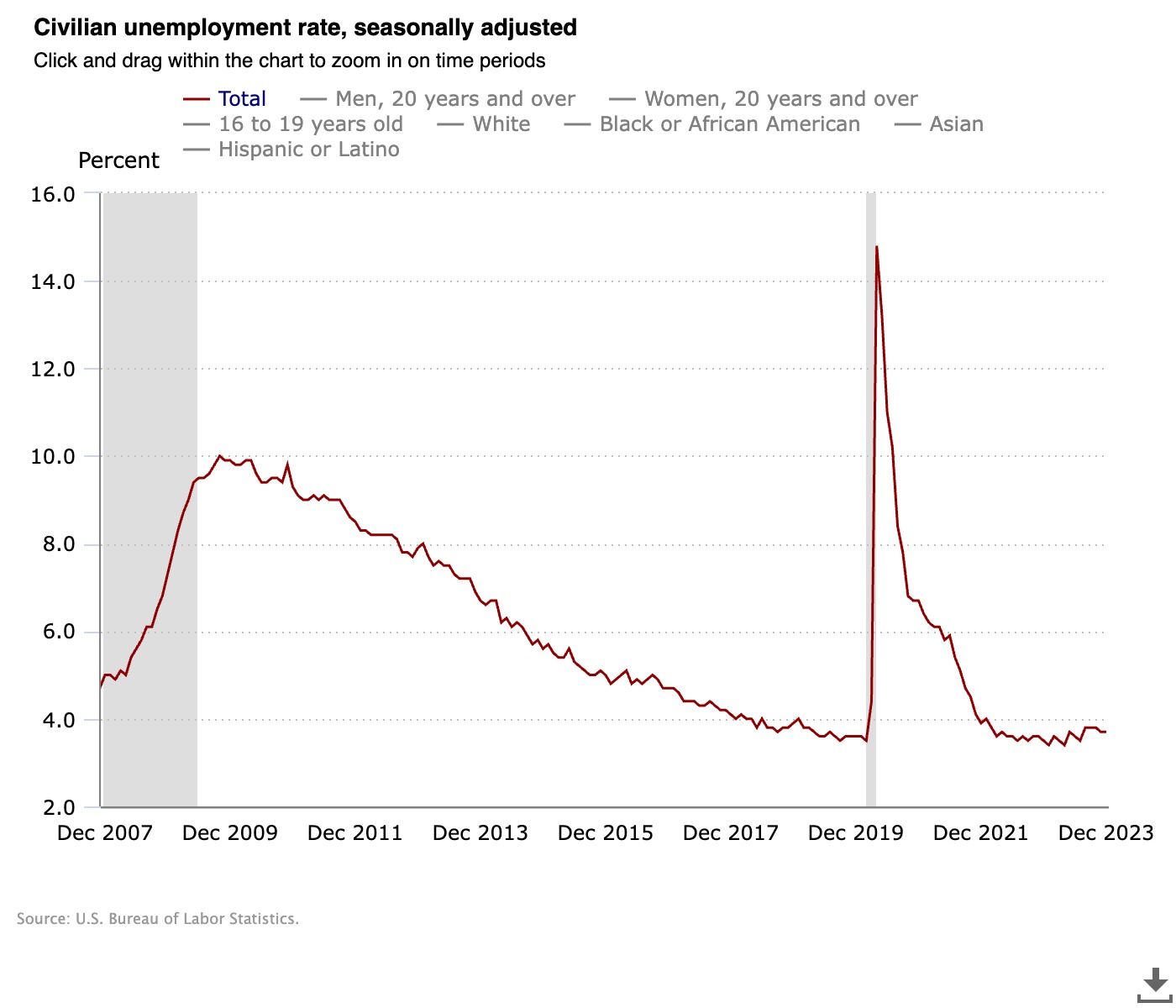

Hiring has remained remarkably strong throughout almost all of the pandemic period but two other indicators of labour market tightness - job openings and employee quits - are moving in opposite directions. To make any downward moves, the Federal Reserve will want to see some (but not too many) signs of loosening in the labour market and falling inflation. While it has only one of the two so far, the two do inform each other.

"Officials aren’t looking for a weaker labour market or a downturn in the real economy. Instead, it would be enough to see 6-month annualised core PCE inflation continuing to run at the 2% target for a few more months," Paul Ashworth, chief North America economist at Capital Economics wrote in a note to clients.

The Fed will also receive two consumer and producer price inflation (CPI and PPI) reports between now and its next meeting as well as one personal consumption expenditures (PCE) report.

The reason I mention the other report is that while the market pays close attention to CPI and PPI, it is the PCE index that the Federal Reserve actually uses to make its calls on interest rates (because it's the only inflation index which is also used in the calculation of GDP/economic growth). Lower inflation equals a higher real interest rate giving the Fed an even larger buffer to cut interest rates when it feels the economy can handle it.

So, set a diary reminder for 29 February - it could be a red-letter leap day in more ways than one.

2 topics