The Fed’s proper fight on inflation is just getting started

Inflation has been kind of an enigma for the world over the past few years.

Policymakers dismissed rapidly rising inflation early on and viewed it as transitory. It was put down to temporary supply constraints, adjusting from the covid pandemic. However, inflation was rising higher and more persistent than initially thought. Whether inflation has been supply driven or demand driven has also been up for much debate.

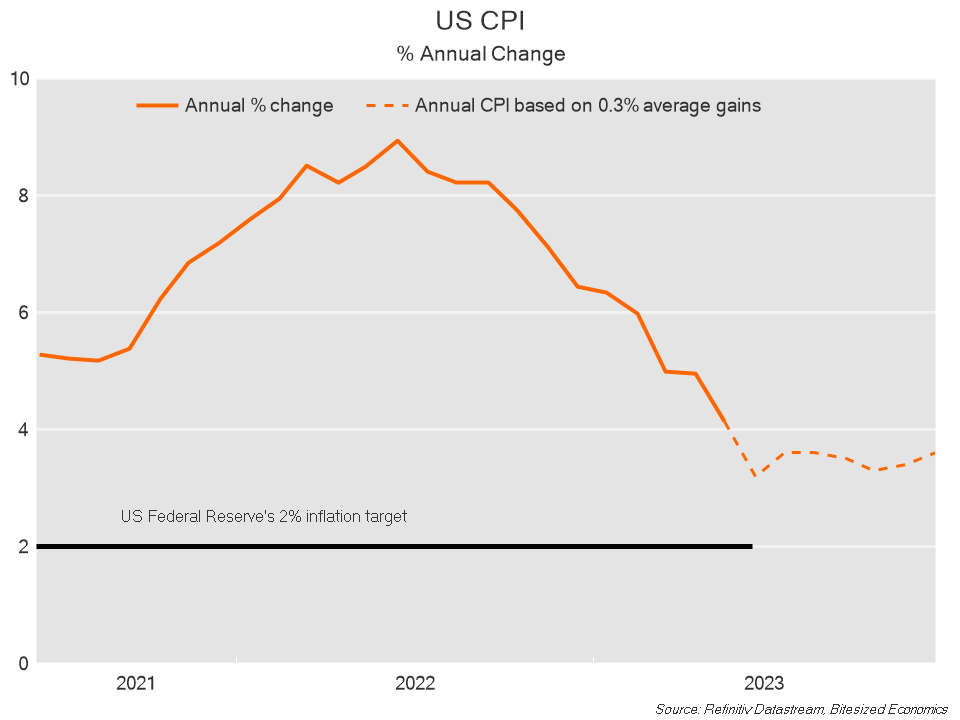

The great news over recent months has been the gradual easing of inflation. As of May, US annual inflation stood at 4.0%, well down on the 9.1% peak recorded June in 2022.

Earlier this year, I said that inflation could hit 3.5% by the middle of this year.

It appears that inflation will be close to that, and possibly even a bit lower in June.

Now for hard part

But beyond June, it isn’t so clear cut that inflation will continue to weaken.

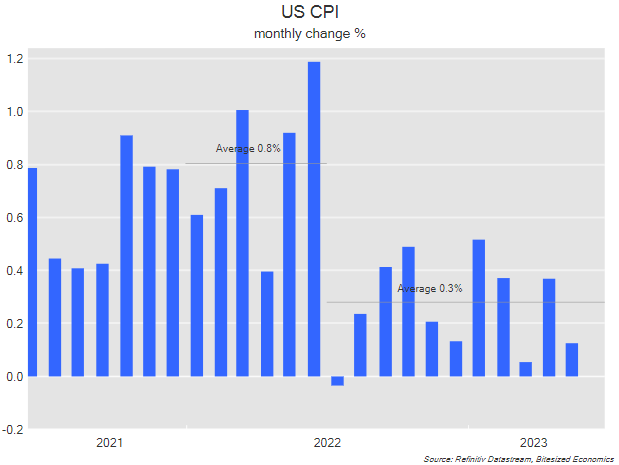

The easiest way to see this is a breakdown of the monthly inflation gains, instead of the annual rate.

Since July of last year, inflation has stepped down significantly after much stronger gains previously. Inflation has averaged 0.3% per month for nearly a year.

That step down has allowed the annual rate of inflation to come down rapidly.

While this easing in inflation is good news, it isn’t good enough. The annual rate of 4.0% is still well above the US Federal Reserve’s 2% target. And if the 0.3% increase in prices per month were to continue, annual inflation will continue to hover above 3%.

Clearly, we are going to need to see inflation ease even further if inflation is going to get to target. Monthly inflation gains of around 0.3% are still too high.

This is reflecting the stickier part of inflation which is harder to come down. That’s because the easy part was simply waiting for those supply constraints that plagued the global economy post-covid to pass. Commodity prices, including oil, other energy sources and industrial metals, along with shipping rates have fallen significantly from their peaks.

To put it another way, there were elements of inflation that were transitory, and now they have passed.

But given inflation is still above the Fed’s target clarifies that inflation was never just a supply issue. It was also a demand issue. It’s the sort of inflation that occurs more broadly across prices and has translated into more stubborn inflation in services and higher wages growth.

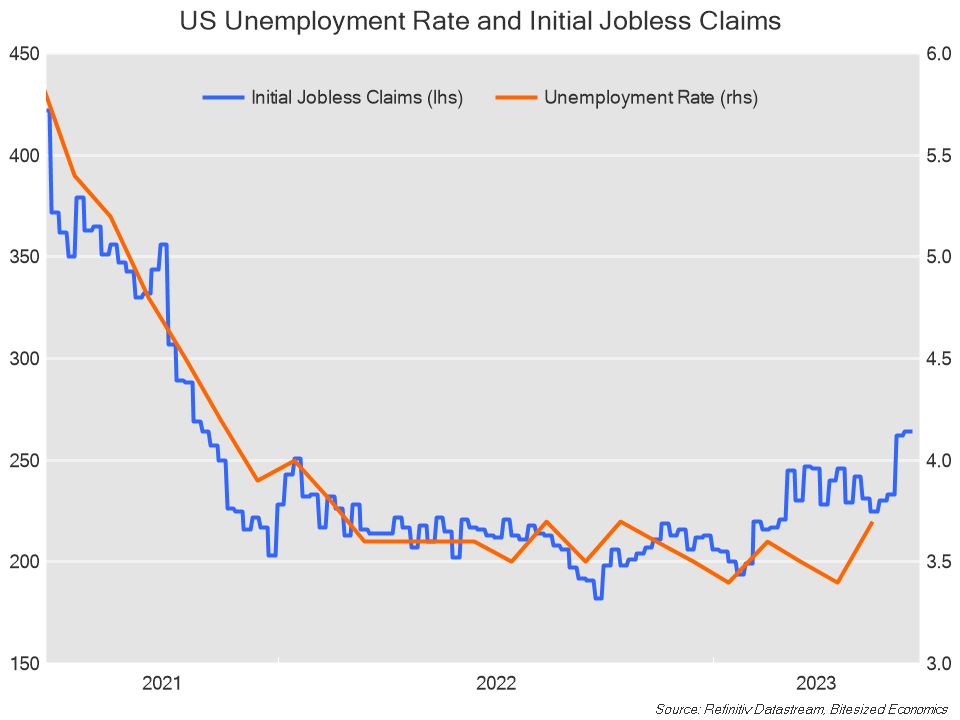

It is why the Fed has needed to engineer a slowdown in the economy. Specifically, it wants to see a higher unemployment rate. Inflation wasn’t going to be able to come down to target without it.

The good news is that the unemployment rate has risen, and jobless claims are rising.

Indeed, the US unemployment rate, currently at 3.7%, has lifted from a low of 3.4% in January of this year.

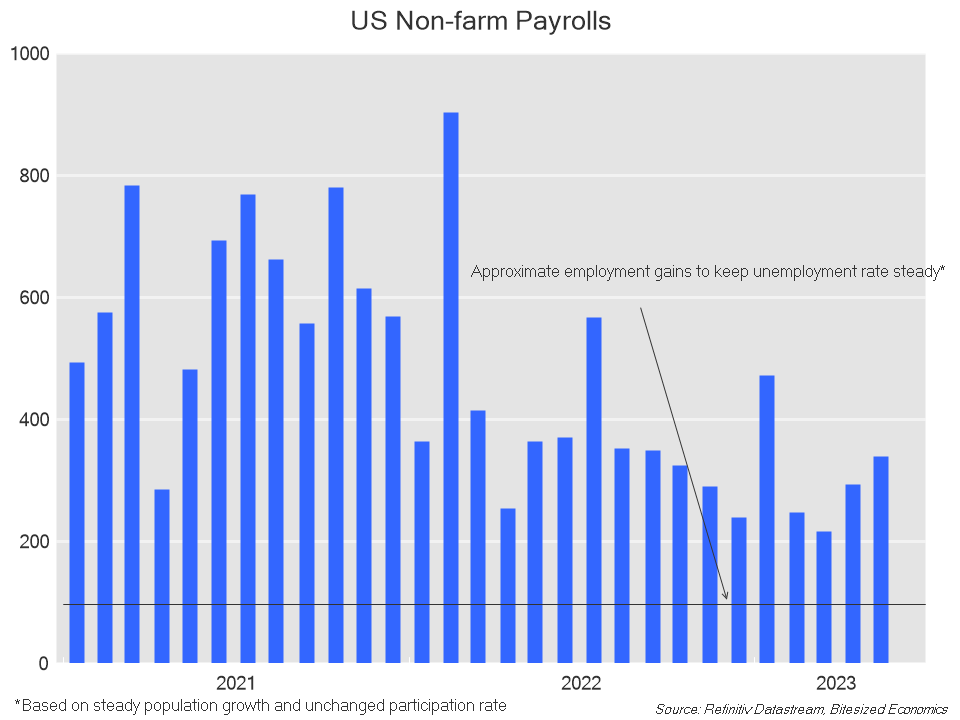

Interestingly, despite this lift in the unemployment rate, US job growth has remained strong. Sure, job growth may have eased from its peak, but gains have continued comfortably above 200k per month. Somehow the US economy has managed to achieve the ideal conditions of ongoing steady job growth, and the desired lift in the unemployment rate.

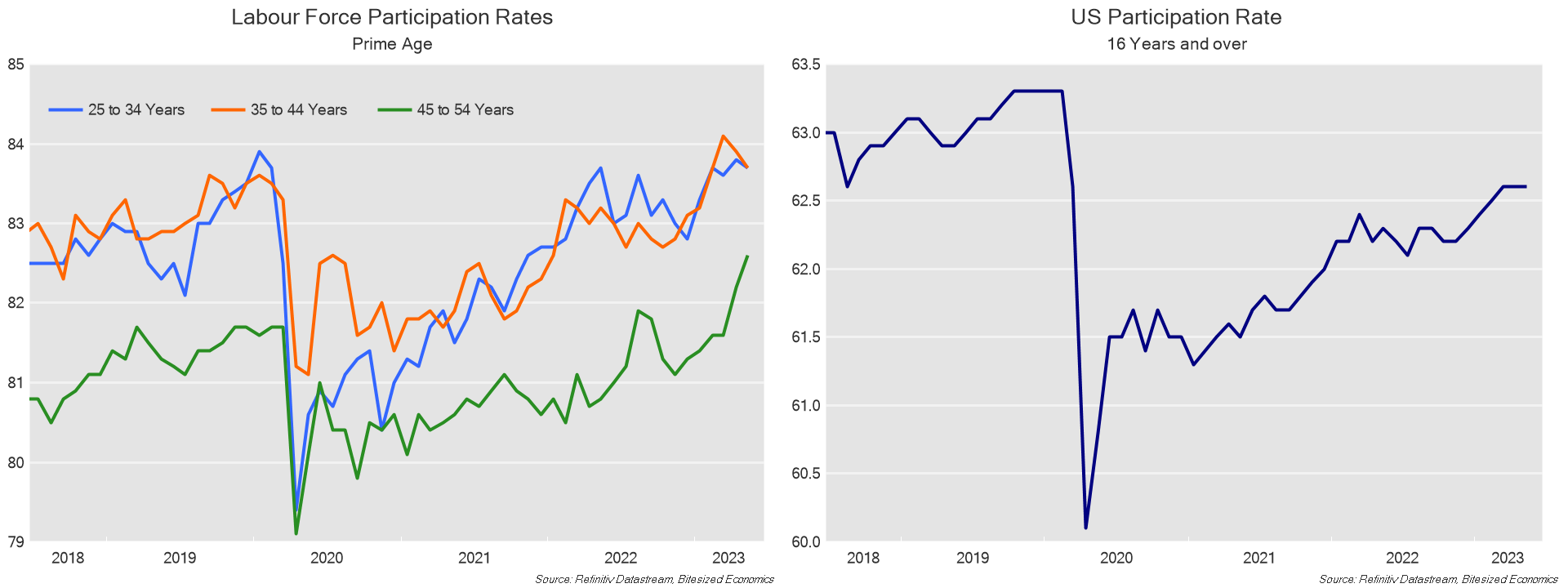

As is usually the case, the key reason for rising unemployment and consistent job growth is stronger work force participation. The participation rate has lifted 0.5 percentage points to 62.6% since July of last year.

Again, this is another example of a temporary constraint on supply because of the pandemic. Remember the “Great Resignation”? When we all reassessed our work life balance in the aftermath of the pandemic? As it turns out, most of those missing workers have now come back.

Workforce participation has not recovered fully back to pre-pandemic levels, but those of prime working age have. Participation rates of some age groups have even increased above their pre-pandemic levels.

Again, this is great that the loss of labour supply from the pandemic has been recovered. However, it also means that further increases in the unemployment rate are not likely going to come from further increases in the participation rate.

All of those drivers of inflation due to those temporary post-pandemic supply factors, are no longer at play. But we are left with inflation continuing to sit above the US Fed’s 2% target.

If the unemployment rate rises further, it is likely going to occur via a substantial weakening in employment.

The Impending Slowdown

Just how much does the labour market need to weaken?

To keep the unemployment rate steady, employment needs to weaken to around 96k per month. That is with the assumption that population growth holds steady at current levels, and the participation rate remains unchanged. So, employment needs to weaken below that for any decline in the unemployment rate.

Of course, current employment gains are well above what is needed for a meaningful rise in the unemployment rate. Indeed, to meet the US Federal Reserve’s unemployment rate forecasts of 4.1% and 4.5% in 2023 and 2024, respectively, employment gains would need to weaken to around 20k-50k per month.

While there are many signs of the economy weakening, such as economic activity indicators, we still don’t see sufficient evidence that employment will weaken to that point.

Of course, the US Federal Reserve has tightened monetary policy significantly - the Fed funds rate has lifted a total 5.0 percentage points in a period of 1½ years, and this is still likely to flow through to weaker demand. But if growth doesn’t weaken materially, then rate hikes, or some other shock, will need to step up until the economy weakens sufficiently.

The point is that inflation will not come down further on its own. From here on now, it has to come from weaker demand, given that the supply constraints from the pandemic have largely resolved itself. The transitory part of inflation is now coming to an end. The harder job of tackling inflation; that is just beginning.

5 topics