The rise of private debt

Key Points:

• Private debt has emerged as an asset class as significant as high yield bonds since the Financial Crisis. Much of this growth reflects the withdrawal of banks from some areas of corporate lending due to increased capital requirements and regulation.

• Private debt is more complex and less liquid than corporate bonds or traditional bank lending. To compensate for this, it offers an attractive return premium.

• For investors who have the ability to accept less liquid investments, we think private debt presents an attractive and complementary opportunity set previously only available to institutional investors.

In this month’s Market Insight, we aim to provide our readers with a user-friendly overview of private debt (or private credit), which after a decade of exponential growth, now rivals the high yield bond market in size. The asset class is an interesting example of how markets adapt to changing circumstance and regulations. It also has many characteristics which are attractive to investors, offering exposure to a sector traditionally underexposed in portfolios. Returns for the asset class over the past two decades have also been strong, with low volatility (see below).

What is Private Debt?

Private debt consists of financing provided by non-bank institutions mostly to private companies. Generally, private debt sits in between public corporate debt markets and bank lending. Private debt borrowers are often smaller or medium-sized companies that are too small for public debt markets and too large (or risky) for the banking system. Private debt borrowers may also prefer due to the need for faster execution or more flexible terms.

There are a number of different types of private debt lending:

1. Direct Lending: This is the most common form of private debt, where lenders provide loans directly to businesses. These are usually senior secured loans, meaning they have a higher claim on the company's assets compared to other debts.

2. Mezzanine Financing: This type of debt is subordinate to senior debt but senior to equity.

3. Distressed Debt: This involves buying the debt of companies that are in financial distress or facing bankruptcy. This is a specialised sub-asset class and not a component of most private debt funds.

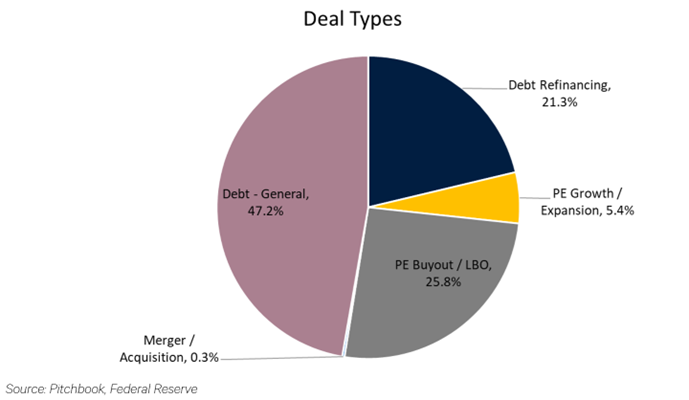

In terms of the use of borrowing, around two thirds is directed towards typical business borrowing with the remainder used to finance private equity buyouts and growth.

Spectacular Growth

Private debt as an asset class and as a source of corporate financing has grown significantly since the Financial Crisis. Following 2008 regulations increased capital requirements and restricted the lending capabilities of banks, especially towards riskier, non-investment grade borrowers.

On the demand side, a growing number of companies prefer private debt over traditional bank lending, despite generally higher borrowing costs. Private debt providers are often more willing to customise loan terms to suit the borrower’s specific situation, including covenants, repayment schedules, and collateral requirements. Private lenders can also provide financing more quickly than banks or public debt markets. The growth of the private equity industry has also contributed significantly to the rise of private debt as they require large amounts of debt to acquire companies. As banks retreated from this space due to regulatory constraints, private debt funds stepped in to provide the necessary financing.

These changes have seen private debt grow from less than a third of the size of the US high yield bond market in 2013 to a similar size in a decade.

What Makes It Different?

From an investor’s perspective, the most obvious differences (holding credit risk constant) between private debt and public credit markets are delayed pricing and a lack of fund liquidity. Little standardisation in the underlying loans, as well as a lack of secondary transactions, makes the value of a private loan harder to determine than a publicly traded loan or high yield bond. As a result, loans are valued infrequently, making the investment appear less volatile than public market investments which are priced daily.

That brings us to the second key difference – liquidity. While the net asset value (NAV) of a private debt fund may not fluctuate with public markets, that doesn’t mean the actual value of the loans isn’t changing. The liquidity of the underlying holdings is low and therefore the liquidity of the fund in which they are housed is also lower than public markets. Much of the universe sits within closed end vehicles, or evergreen funds which have only monthly or quarterly valuations and redemptions, with provisions for gating (closing to redemptions) should market conditions or portfolio issues require.

In terms of the true risk of the underlying investments, specifically, losses, private debt is unsurprisingly in the same ball-park as other lending and high yield bonds (see below). Private debt tends to have a lower default rate than high yield debt probably reflects covenants better suited to assessing the risk of underlying borrowers (given the more flexible nature of the asset class) and the ability for lenders to renegotiate flexibly with a relatively small group of creditors when borrowers are in distress.

What’s the Catch?

Private debt is loosely regulated, particularly compared with the banking sector. By making it more difficult and costly for banks to lend to middle market corporates or private equity funds embarking on leveraged buyouts, regulators have pushed risky borrowing out from under their gaze, into a shadow banking system. From a financial system stability perspective, that would normally be seen as a problem. However, that may not necessarily be the case in this instance.

Banks are highly leveraged institutions whose smooth functioning is vital to the broader economy. They need to be regulated to within an inch of their life because experience has shown us that the alternative is regular financial crises. Most of the underlying providers of capital in private lending are pension / superannuation funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds. These investors are generally not highly leveraged, have very long-term investment horizons, and can wear losses with limited ramifications for the broader financial system or the economy.

While these perfectly matched investors are the largest providers of capital to the asset class, they are not the only ones. The opacity of the asset class makes analysis difficult, but recent research has shown a growing interdependence between private credit lenders and the banking system. Regulators are not naïve to this, and we expect the regulatory burden on private debt to increase in the years ahead in an effort to stymie problems before they arise.

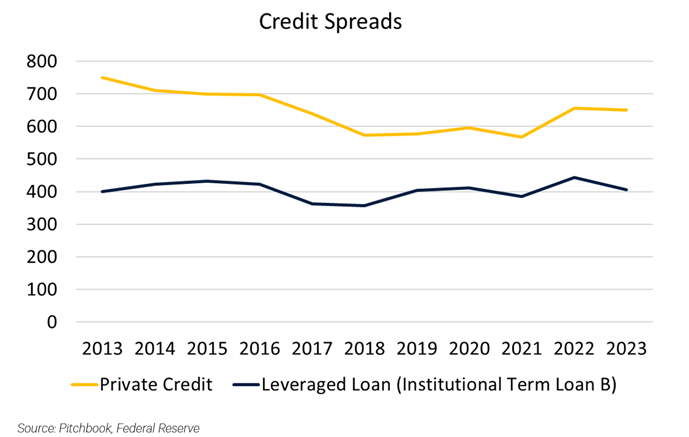

Private Debt in a Portfolio

We think private debt has a role to play in the portfolios of investors who are willing and able to accept the illiquidity that comes with the asset class. Historically, the asset class has delivered an attractive spread above other corporate lending with similar levels of risk (see below) and much lower realised volatility. We think this is due to the illiquidity and complexity of the asset class. Essentially, investors demand and have been delivered an illiquidity and complexity premium.

It is important to realise that the illiquidity premium generated from private debt is not “free.” In times of serious market crisis evergreen funds as a whole are unlikely to be able to provide the liquidity offered during calm markets. Investor money can be locked up for meaningful lengths of time to prevent the fire-sale of assets. Somewhat ironically, this can be to the benefit of the investors in the vehicle.

Because of the complexity of the asset class, manager selection is arguably more important than in public markets. The dispersion of returns across managers is likely to be greater given the idiosyncratic nature of the underlying investments and the more concentrated nature of the portfolios versus a public credit portfolio. A good understanding of the fund managers and their underlying investments also gives insight into which funds are more likely to be able to meet their liquidity targets.

In investing, excess returns are never free (or easy). Private debt is no exception. However, we think pairing detailed due diligence on the investment manager side with the ability to accept less liquidity on the investor side is a good recipe for better portfolio outcomes overall.

1 topic