The threat to Australian house prices from coronavirus

The Australian housing market was boosted from mid-last year by the combination of the Federal election removing the threat of changes to negative gearing and capital gains tax, rate cuts and regulatory easing. So, after a 10% drop in average capital city prices into mid-last year - the biggest fall in property prices for at least 40 years - they have since rebounded by 9%. Our assessment was that price increases would slow from the pace seen since mid-year, but that the combination of low rates, solid population growth and the fear of missing out would still see solid price growth this year.

However, the coronavirus pandemic & associated shutdowns to economic activity now poses a significant threat to the outlook for property prices. The question is how big the threat is?

Social distancing will likely delay property transactions

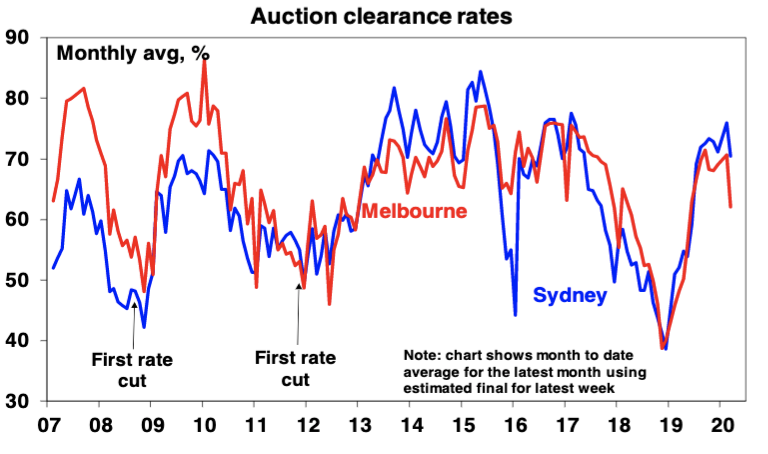

The absence of many Chinese buyers flowing from travel bans appears to have had little impact on property demand with clearance rates remaining strong in February.

However, auction clearance rates and sales momentum are

showing some signs of slowing this month. This may reflect an

increasing desire on the part of buyers and sellers to put

property transactions on hold to avoid being exposed to the

virus unnecessarily. Social distancing policies will only intensify

this. On its own this may crash transactions but may just flatten

price gains.

Recession is the big threat

However, it’s the likely recession that we have now entered due

to coronavirus related shutdowns that imposes the big risk. We

expect at least two negative quarters of GDP growth in the

March and June quarters with the risk that the September

quarter is also negative. And the contraction could be deep

because big chunks of the economy will be largely shut –

tourism, travel, and entertainment with a severe flow on to parts

of retailing. The toilet paper, sanitiser and canned/frozen food

boom may help supermarkets for a while – but as Deutsche

Bank recently calculated for every $1 spent on such items there

is $15 spent on things that are vulnerable to social distancing.

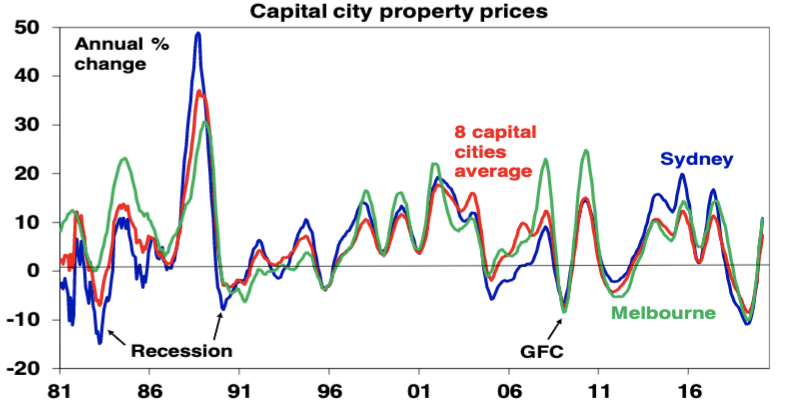

Past large share market falls have seen a mixed impact on

property prices. The 1987 50% share market crash actually

boosted home prices as investors switched from shares to

property. But the key is what happens to unemployment as this

often forces sales and crimps demand. Back in 1987 the

economy remained strong and unemployment fell but the

recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s saw falls in

average national capital city home prices of 8.7% and 6.2%

respectively as unemployment rose. The GFC share market fall

of 55% also saw a 7.6% home price fall, even though it wasn’t a

recession, because unemployment rose from 4% to nearly 6%.

So, a lot depends on how deep the recession is and how far unemployment rises. Our base case is for a rise in unemployment to around 7.5% which is likely to drive a 5% or so dip in prices ahead of a property market recovery into next year as the economy bounces back and pent up demand is unleashed again helped by ultra-low interest rates. Government and RBA measures to help struggling businesses and households through the coronavirus shutdown should help in preventing a really big rise in unemployment.

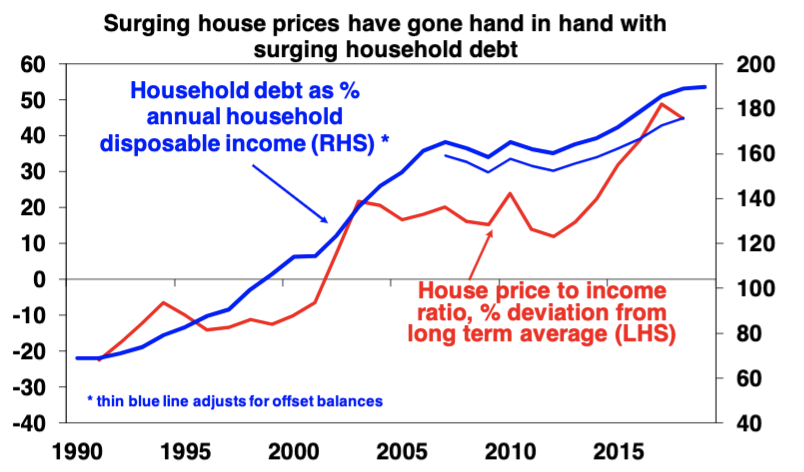

However, if the recession turns out to be long – pushing

unemployment to say 10% or more – then this risks tripping up

the underlying vulnerability of the Australian housing market

flowing from high household debt levels and high house prices.

The surge in prices relative to incomes (and rents) over the last

two decades has gone hand in hand with a surge in household

debt relative to income that has taken Australia from the low

end of OECD countries to the high end.

This is nothing new and we have long described it as Australia’s

Achilles’ heel. Some things have given us a bit of confidence in

recent times prices won’t just crash spontaneously.

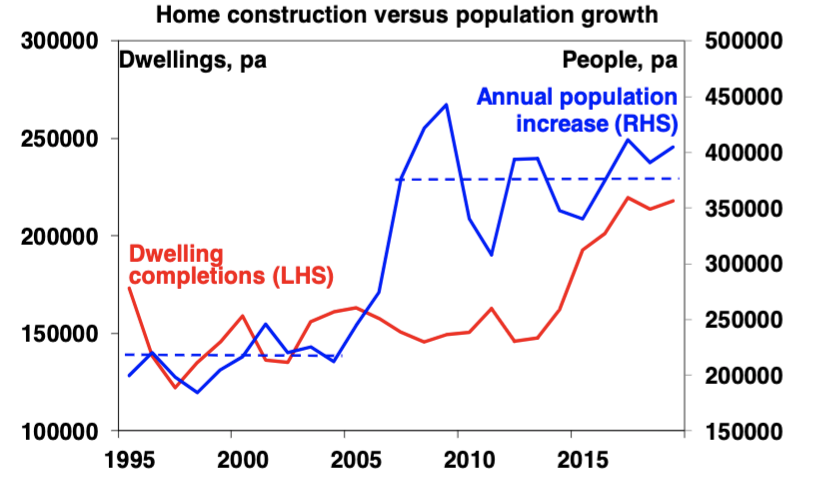

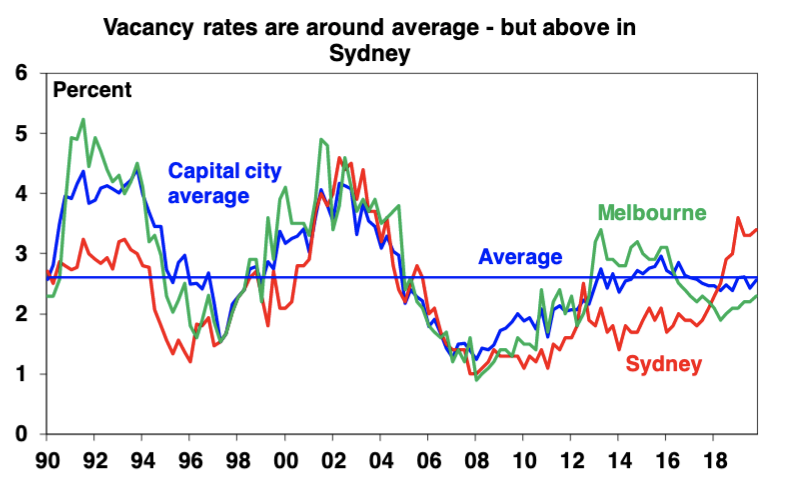

• First, the property market has been chronically

undersupplied. Annual population growth since mid-last

decade has averaged 373,000 people compared to 217,000

over the decade to 2005, which requires roughly an extra

75,000 homes per year. Unfortunately, the supply of

dwellings did not keep pace with the population surge (next

chart) so a massive shortfall built up driving high home

prices. Thanks to the surge in unit supply since 2015 this

has been reduced but capital city vacancy rates are still

around their long-term average indicating a lack of over

supply, although Sydney may be more at risk.

• Second, talk of mortgage stress has been overstated.

Despite some seeing negative equity into mid-last year and

a significant proportion of borrowers switching from interest

only to principle & interest loans over the last few years

(which has seen interest only loans drop from nearly 40% of

all loans to 18%) there has been no surge in forced sales

and non-performing loans. While Australia saw a

deterioration in lending standards with the last boom, it was

nothing like other countries saw prior to the GFC. Much of

the increase in debt has gone to older, wealthier

Australians, who are better able to service their loans.

We have always concluded that the combination of high prices

and debt on their own won’t trigger a major crash in prices

unless there are much higher interest rates or a recession.

Unfortunately, we are now facing down the barrel of the latter. A

sharp rise in unemployment to say 10% or beyond risks

resulting in a spike in debt servicing problems, forced sales and

sharply falling prices. This could then feedback to weaken the

broader economy as falling home prices lead to less spending

and a further rise in unemployment and more defaults and so

on. This scenario could see prices fall 20% or so.

Bear in mind though that part of this would just be a reversal of

the 9% bounce in average capital city prices seen since midlast year.

It’s also not our base case but it highlights why governments

and the RBA really have to work hard to avoid letting the virus

cause a lot of company failures, surging unemployment and

household defaults.

3 topics