The unfair advantage of private equity

The strong returns delivered by private equity are well documented.

As a practitioner, I wanted to provide perspectives on why this might be the case: a first-hand account, so to speak, of factors that may help explain why private equity has tended to outperform the listed markets.

Most of what I’ll discuss relates to inherent structural features of both markets. It's surprising how often these differences are overlooked or undervalued. They're second nature for investors in the private market, but one is still frequently reminded of just how significant an advantage they create for the private market investor.

Before I begin, I should declare my bias.

Having worked in both markets – initially as an investment banker advising listed company clients, and subsequently as an investor in the private market – I have a strong preference for investing in the private market. As I see it, the benefits of the private market are just far too great.

What I mean by the ‘private market’

By ‘private market’, I mean investments in the shares of private operating companies. This doesn't include private debt, real estate or infrastructure. Essentially, private equity.

Private equity itself is a broad term. It can encompass strategies such as leveraged buyouts, turnarounds, venture capital and growth equity. There are important nuances between each of these, and the methods and practices can differ. Still, many topics covered in this article hold true across the private equity spectrum.

For complete context, I am writing this note from the position of a growth equity investor in small-to-medium businesses.

Growth equity sits between venture capital and leveraged buyouts. The companies we invest in would usually be considered ‘too boring’ for venture capital and ‘too small’ for leveraged buyout firms. Which is exactly how we like it.

Growth equity investors typically invest as a minority shareholder, partnering with the existing shareholders and supporting them as they work to grow their business. Little or no debt is used, seeking to generate returns through business growth rather than from financial leverage, aided by a focus on companies that have ample room for continued growth.

Cambridge Associates published an article describing growth equity as an asset class back in 2013 Cambridge Associates: Growth Equity is All Grown Up.

Private equity outperformance

“The most in-depth research continues to affirm that, by nearly any measure, private equity outperforms public market equivalents.” McKinsey & Company April 2021

Multiple studies and statistical benchmarking reports document the impressive performance of private equity. A few examples include:

-

BlackRock: On the Historical Outperformance of Private Equity

- McKinsey: Global Private Markets Review 2021

- Australian Investment Council / Cambridge Associates: Australian Private Equity and Venture Capital Performance Statistics

The important role that private market investments can play in a portfolio was also reflected in the Future Fund’s Position Paper, published in September 2021 (Position Paper - A New Investment Order)

As stated by Peter Costello, Future Fund Chairman:

“We think we will have to allocate more into private markets than public markets.”

Source: (VIEW LINK)

Why private equity delivers superior returns

This piece highlights some of the fundamental distinctions between private and public equity investing which may explain why private equity has delivered superior returns.

It is far from comprehensive in explaining the differences, but it discusses some key advantages that the private market offers for the investor. In particular:

- There are far more opportunities

- Valuations tend to be more attractive

- It's a better environment for building a business

- Investors have an information advantage

- Investors can support the business and help guide the outcome

- Investors can participate in an ‘exit uplift’

1. There are far more opportunities

Listed companies represent just a small subset of the total universe of companies.

This is an obvious statement, of course. But it is an instructive place from which to begin a comparison of public market investing vs private market investing.

Investments in the public market, by definition, are limited to companies that decided – at some point in their lifecycle – that it was in their interests to become public companies.

Depending upon your investment criteria, this can be a very small list.

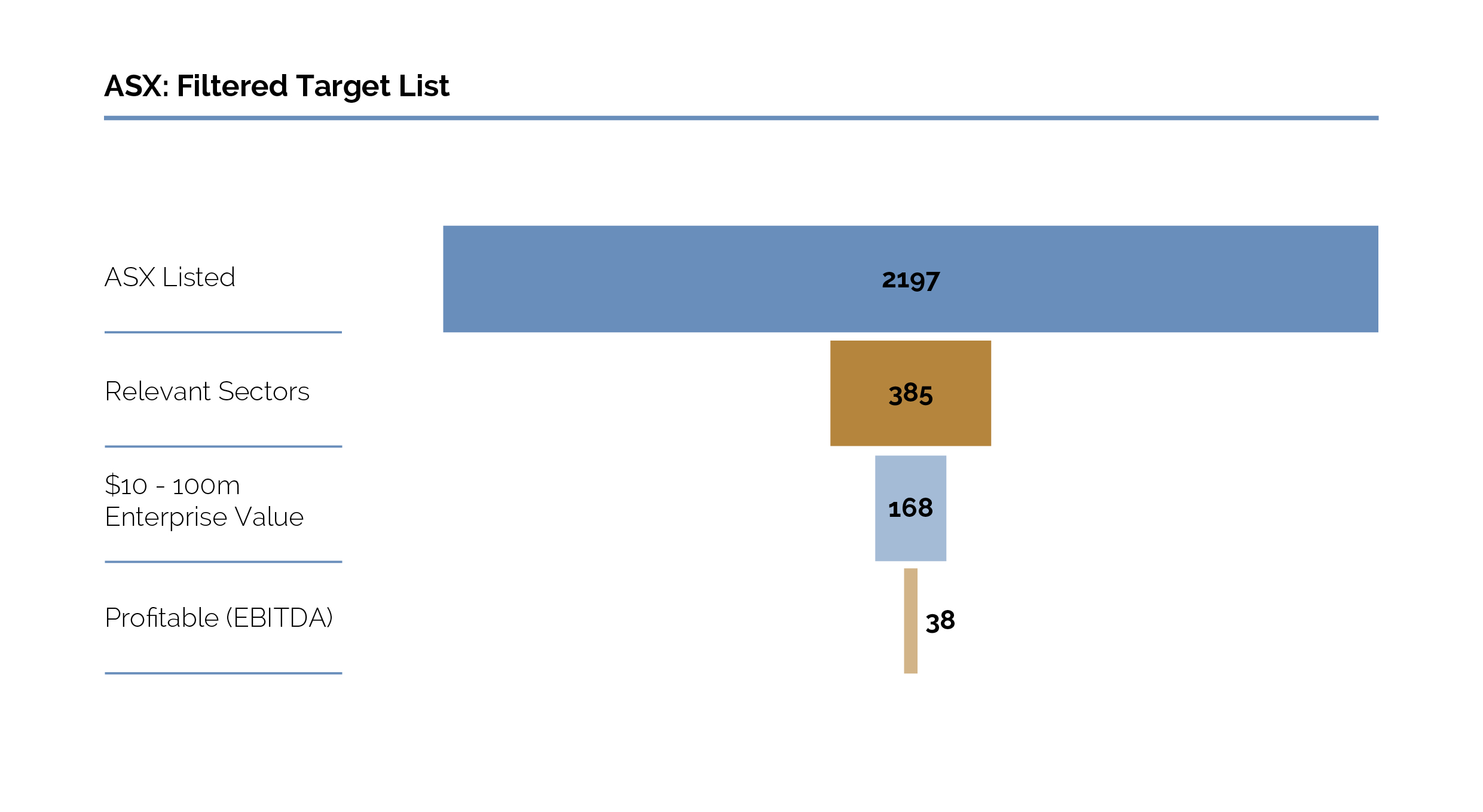

The experience will differ across the private equity spectrum. For example, the proportions look different for a billion-dollar leveraged buyout investor. But for a growth equity investor at the smaller end of the market, the comparison is stark. The number of companies on the ASX that fit the mandate is remarkably small.

Let’s look at the numbers.

I’ve applied the same criteria here that we’d apply to our work in the private market. Namely, a business must:

- be profitable

- be of a relevant size, and

- operate in one of our focus sectors.

I’ve included companies with an enterprise valuation of $10 - 100m and which are classified within the consumer staples, consumer discretionary or healthcare sector groupings.

At the time of writing, there were 2,197 companies in total listed on the ASX. Filtering for sector, the list reduces to 385. Filtered further for size, the list becomes 168. And of these companies, only 38 are generating positive EBITDA.

For small cap investors, the available options are mostly 'cash burn' business models

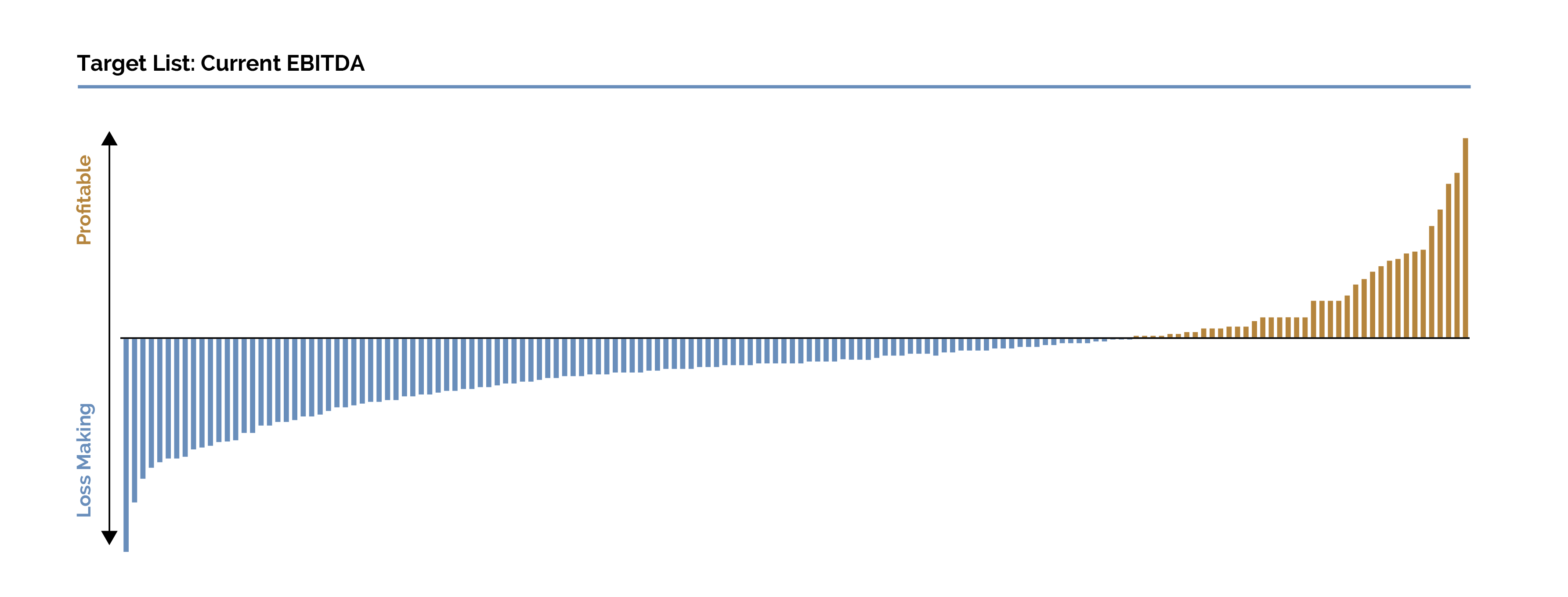

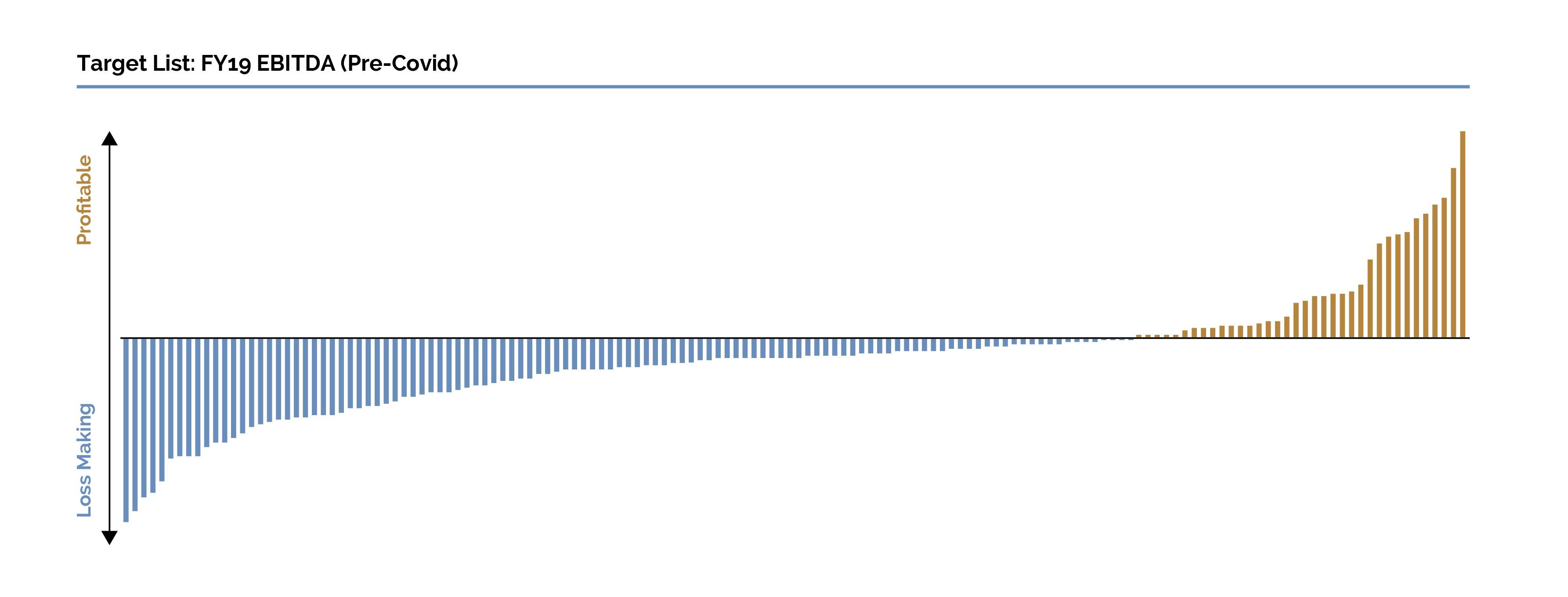

The distribution of profitability is also quite revealing. The first chart below shows annual EBITDA for each of the 168 companies in our sectors that have a valuation of between $10 - 100m. This profile is not a COVID effect – the second chart shows EBITDA (reordered) for the 2019 Financial Year.

The vast majority are loss-making companies. And this list excludes the technology sector.

This perhaps speaks to the role and function of an ASX listing for these smaller companies. They require capital to fund ongoing company operations, and the listed market offers access to that capital. Or, perhaps more correctly, it offers access to what the company considers to be relatively cheap and plentiful capital relative to what is available to them as a private company.

I think it is a fair comment that these companies tend to sit towards the ‘speculative’ end of the investment spectrum.

The challenge is not just that the list is small, but also that everyone has access to the same list.

This removes the reward that comes from discovering a ‘hidden gem’. Many investors, particularly in the smaller end of the market, will have experienced the unlikely discovery of a truly exceptional company. Sometimes this may be in an obscure niche, or with uncommon financial metrics, which reveal a rare and valuable find.

Many of the most successful private market investments share a backstory of this nature.

Many good companies don’t want to list – or are yet to list

It’s difficult to precisely quantity the number of private businesses that fit within the same criteria.

As a starting point, there are approximately 56,000 medium-sized enterprises in Australia (defined as between 20 and 200 employees).

As a guide, we usually meet 50 - 100 new businesses each year that fit within the filters applied above. And we know that we’re merely scratching the surface.

Within this group of private companies, there are exceptional businesses. The best often don’t need capital. Instead, some bring in an outside investor to benefit from the expertise, networks and perspectives that the investor can contribute. In others, shareholders might wish to monetise a portion of their shares whilst continuing to run their business as a private company.

For most, there’s little desire to seek a public listing, particularly when you consider that shareholders of private companies tend to value their privacy.

2. Valuations tend to be more attractive

Liquidity is expensive

The ease and efficiency with which an investor can buy and sell shares in a public company is phenomenal.

Barriers to entry in the public markets, which many years ago were not insubstantial, have completely disappeared.

An investor can now create a new trading account in the morning, construct a portfolio by lunchtime and – should they wish – exit their positions that same afternoon.

But this incredible liquidity comes at a very high cost.

Ease of access to the market facilitates greater demand for the same (limited) set of stocks. In a prolonged bull market, this impact is heightened, as more and more capital rushes effortlessly and enthusiastically into the market.

As a result, any investor wanting to buy shares in a company is forced into an open auction against all comers. And the competing bidders can be as irrational as they are numerous.

Competing bids come from both small retail investors as well as large institutional investors. By way of example, a large superannuation fund must, of necessity, hold a large portion of its funds in liquid assets. Listed equities are one such liquid asset, and so there flows the capital.

Barriers to entry in the private market

By contrast, significant barriers to entry remain in the private market.

The market is opaque. It takes dedicated resources, applied consistently and systematically, sometimes over long periods of time, to find suitable opportunities. It then requires skill, experience, and resources to secure, negotiate, execute, and manage the investment.

Retail investors may desire access to a private company, but they’re in no position to make a relevant offer. At the smaller end of the market, large institutions simply can’t get enough capital to work quickly enough to justify the effort.

This creates a supply and demand dynamic that works in favour of investors, rather than against them.

Through the lens of a growth equity investor in small-to-medium businesses, this supply and demand imbalance is profound. High-quality investment opportunities are ample, but there’s a shortage of investors with the requisite expertise, resources and capital to make the investments.

Long live illiquidity

Private markets are certainly less liquid than public markets – significantly less so.

That’s one reason we like them.

Now, if the investment objective is to maximise liquidity, then it’s wise to steer clear of private markets. These markets are only suitable for those able to withstand illiquid positions within their overall portfolio. Because of this, access invariably skews towards those with large portfolios – namely institutions, family offices and wealthy individuals.

But for those able to invest, the benefits are significant.

Knowing an investment is illiquid also forces the investor to focus on the medium-term prospects for the business. And removes the temptation to trade on every short-term fluctuation than occurs along the way.

“I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for five years.” Warren Buffet

3. It's a better environment for building a business

Privacy can be underrated.

For all the hype and publicity of an IPO or life as a public company, many successful business owners much prefer the humble work of building their business.

Time is precious, and focus is critical.

Place yourself in the shoes of the owner of a successful small-to-medium sized business. Let’s say you’ve gradually built the business over several years of hard work, and it’s now generating a profit of $5m per year with growth of 20% p.a. That is a good place to be, and a strong foundation to pursue future success.

A public listing could deliver a nice payday. But suddenly you are required to share sensitive financial information about your business (with the public, which includes your suppliers, competitors, staff, friends, and extended family). Then, at least twice per year, you’re asked to front external analysts and possibly the media. You now have an investor relations department and a heavy compliance burden that costs you time, money and focus.

Promoting the company in the public market can involve a set of activities very different to (and sometimes conflicting with) the work of building the business. Educating the market on your strategy, for instance, might be well received by your investors, but also greatly appreciated by your competitors.

Bumps in the road also often play out publicly and live on permanent record. And decisions made to benefit the company in the long term can have negative near-term consequences. Frequent outside commentary and daily share price movements can test the mettle of even the most disciplined business leaders.

Meanwhile, in the private market, you can simply get on with the task of building the business, knowing that success in that endeavour is what really matters for long-term shareholder returns.

4. Investors have an information advantage

There’s a good reason that a potential acquirer of a listed company requests due diligence before making a binding offer. By implication, they consider the publicly available information to be insufficient for making a prudent investment decision.

It’s not practical, of course, to facilitate a due diligence exercise for everyone. Instead, it’s a necessary feature of the public markets that investors must do their work based on limited information.

Annual reports, trading updates and management presentations are useful. But they are prepared and published by the company itself, for whom the primary motivation can be to promote rather than inform. Minimum standards can assist (e.g. external audits, continuous disclosure obligations) and larger investors may be afforded additional access, but the information remains limited, certainly steering clear of anything deemed ‘commercially sensitive’.

In the private markets, however, thorough due diligence is par for the course.

Done well, due diligence is an open-book, no-holds-barred, comprehensive review of any aspect of the business that an investor views as important to making the investment decision.

It's broad, covering all manner of topics – from legal, financial and tax, to wider topics such as operations, supply chain, technology, employee pay audits and regulatory compliance.

But it’s the depth that can really make the difference. Rather than high-level company-published information, the investor receives raw data, working files and internal planning papers. This might include reading the full terms of supplier and customer contracts or observing staff turnover rates across the organisation combined with corresponding exit interview notes.

Consider what one might learn from high-level revenue numbers in an annual report, compared with a forensic analysis of sales and profit margins that are split by product, customer and geography, then shown as a monthly trend over several years. How important is a particular customer? New products might be generating growth, but does real profit reside only in the legacy products?

A judgement on the people is just as important, if not more so, than a judgement on the business. And perhaps more determinative of the eventual outcome for an investor. It is the coffees, lunches, and dinners with the leaders of the business. Not to mention in-depth strategy workshops, planning sessions, site visits and opportunities to meet their broader team.

It can be a time-consuming and costly exercise, for sure. But the knowledge gained is well worth the effort.

And the advantage is not just for the buying decisions. Just as importantly, it informs the hold and the sell decisions that an investor must also make.

The information advantage is large on the way in, and it grows exponentially from there.

After making the investment, the investor becomes an insider. They become privy to board meetings and internal deliberations. A participant in strategy and planning workshops. And they have access to regular trading updates and insights across all facets of the business.

5. Investors can support the business and help guide the outcome

One of the most advantageous aspects of the private market is an investor’s ability to support the business. Indeed, this is often the primary reason the company takes in an investor. The expertise, networks and capital an investor provides augment the skills and experience of the internal team – helping them to navigate key strategic and operational matters and preparing them for a successful subsequent exit event.

This support also plays into the valuation dynamics. This is particularly true for a minority growth investor, where obtaining the support of the right investor can be more important for existing shareholders than simply maximising the valuation of the immediate transaction.

In addition to the support provided, a private investor has the benefit of both formal and informal points of influence to protect the investor’s interests and help shape the destiny of the company:

- formal, in the sense of Shareholder Agreements, Board seats and bespoke deal terms.

- informal, through trusted relationships and regular discussions and collaboration.

In the public markets, an external investor is a passive spectator. The separation between investors and the management team is large, and there are very limited opportunities for an investor to either provide support or influence the conduct of the business.

6. Investors can participate in an exit uplift

A private company has flexibility and choice – perhaps the two most valuable ingredients – when seeking to maximise the proceeds when exiting an investment.

It can pursue an IPO, sell to a trade buyer or bring in a private equity investor.

For the right business, an IPO can deliver an exceptional valuation, often far greater than what is available in the private market. The public market investor is the buyer in this scenario, rather than the seller, and is paying away this premium to the private investors.

An IPO doesn’t always provide the best outcome. Trade buyers may be willing to pay more to acquire the whole business, aided by synergies, and perhaps motivated by a rare opportunity to take out a competitor. Similarly, a sale to private equity can be superior, particularly where creative structuring can generate a win/win for both buyer and seller.

Of course, a public company can also be sold to a trade buyer or to private equity. But these transactions occur within a highly regulated public takeover regime. It’s a process that can (rightly) put off both buyers and sellers from participating. Offers perhaps more freely emerge at the wrong time, when share prices are depressed and buyers are acting opportunistically.

As those in the business of selling private companies know very well, having multiple options up your sleeve (and the flexibility to craft the right deal) can make all the difference.

Conclusion

The private market is a different world to the public markets.

Building a portfolio of investments in high-quality private companies takes time and requires an ability and appetite to invest for the medium term.

But for those who are willing and able to walk the path, the rewards can be significant.

I am now a contributor on Livewire

I am so pleased that I am now an approved contributor on Livewire. For instant access to my insights on Private Equity and how we are approaching it at Edison Partners through the Edison Growth Fund please hit the FOLLOW button below.

3 topics