This is the world's biggest social and economic risk

Australian Ethical

Real change is needed now if we have any hope of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Even during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when much of the world's economies came to a screeching halt, global emissions were only reduced by 6.4%, or 2.3 billion tonnes (which was significantly less than climate researchers expected).

We need to be making expert science-based and evidence-based choices. If we don’t, we are going to be in all sorts of trouble. And we already are in trouble.

Australians need no reminder of the devastating consequences of rising temperatures. And as the planet warms further, we can expect more frequent and more severe storms, floods, droughts and bushfires.

Even without strong climate policy and action (it was only 2017 when the now Prime Minister Scott Morrison held up a chunk of coal in parliament), we’ve already seen massive innovation and investment within this sector, helping to reduce the costs and accelerate the takeup of low emissions technologies.

That will need to accelerate to meet the climate commitments of governments around the world. For example, by 2030, global annual new solar and wind energy capacity will be added at four times the current rate. Electric vehicle sales will be 18 times 2020 levels.

To kick off Livewire's Decarbonisation Megatrend Series, I delivered a keynote on the things investors need to know about climate change over the coming decade and where to find out more, including my thoughts on key minerals, gas and hydrogen, and the changes we will need to make in our personal lives.

You can watch the video or read the transcript below.

Edited transcript

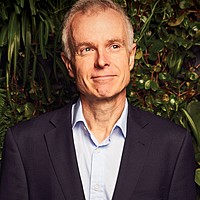

The biggest social and economic risks we face this decade are related to climate change. Failure to take action on climate, biodiversity loss, and natural resource crises are the things that both have a high risk of occurring over the decade and that will have the biggest social AND economic impacts if they do occur.

These are the things we need to think about most.

That’s what the latest Risk Report from the World Economic Forum tells us, but I don’t think we need to be experts in risk or climate science to see that. But where we do need to find and use good experts is when we start taking action to manage climate risk and position ourselves for climate opportunity.

While the direction of travel and urgency for action is clear, there’s real uncertainty about the particular paths that governments, industries and companies will take; the pace of change; about the winner and loser technologies. And about how our planet will respond to not only human carbon emissions but also to our other impacts on the planet as our numbers, as our consumption, and as our environmental footprint grows.

So with the help of some Decarbonisation Worldle, I’m going to introduce you to some experts, some expert resources, and some expert frameworks for finding out more about the climate challenge, and the climate opportunity.

Accessing this expertise is essential if we are going to have any hope of limiting warming to 2, and to 1.5 degrees; if we are going to have any hope of investing in a way which both helps achieve our climate objectives as well as achieving our financial return objectives.

We need to be making expert science-based, evidence-based, well-informed decisions and choices. If we don’t, we are going to be in all sorts of trouble. And we already are in trouble.

Warming above pre-industrial levels is already over 1 degree, and it’s been rising rapidly over the last century. We’re already living with the effects of that warming with more frequent and more severe storms, floods, droughts and fires.

How do we know this?

This and a lot of the other information I’ll be sharing is taken from the latest climate assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC. These reports are the work of hundreds of scientists reviewing tens of thousands of scientific papers, and reporting what we know from those papers, as well as what we’re still uncertain about.

The 2021 and 2022 IPCC reports address what we know about:

- The causes and extent of climate change.

- The physical impacts of climate change on people, animals and the environment.

- Its economic impacts.

- The pathways for limiting climate change through technological shifts in our energy, transport, food and building systems.

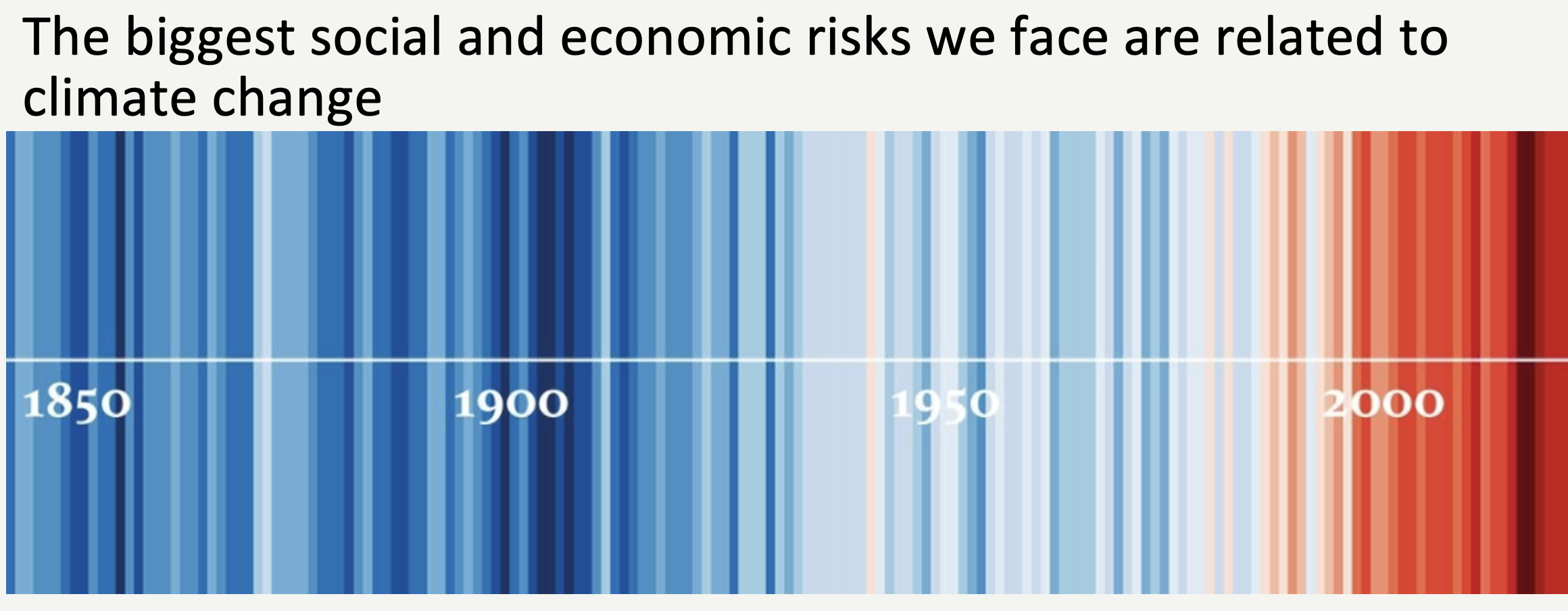

So what are the physical impacts of these increasing temperatures?

There are many, let’s use rainfall as an example.

Some parts of the world will get more rain, some will get less. And those rainfall changes will be greater with greater amounts of warming. Parts of Australia will be 10% wetter, parts 10% drier, and depending on the degree of warming there will be 20 to 30% lower rainfall in some important agricultural areas including our West Australian wheat belt.

Rainfall not only affects drought and flood risk, it also affects bushfire risk and disease risk. Higher and lower rainfall will change where and how we grow food, where and how we live, and where and how we work.

And this is just the shift in average rainfall.

With temperature increase, comes greater volatility and extremes of weather. On the Eastern coast of Australia we can expect to see lower average rainfall with higher warming, but this summer it’s only too clear that particular months, and particular years, can still bring extremes of rain and flooding.

We can expect these extreme rain and heat, and storm and fire events, to become more extreme and more frequent.

The manifest reality of climate change impacts today is shifting government and corporate behaviour to act more urgently to limit the extent of warming, to decarbonize our economy more rapidly.

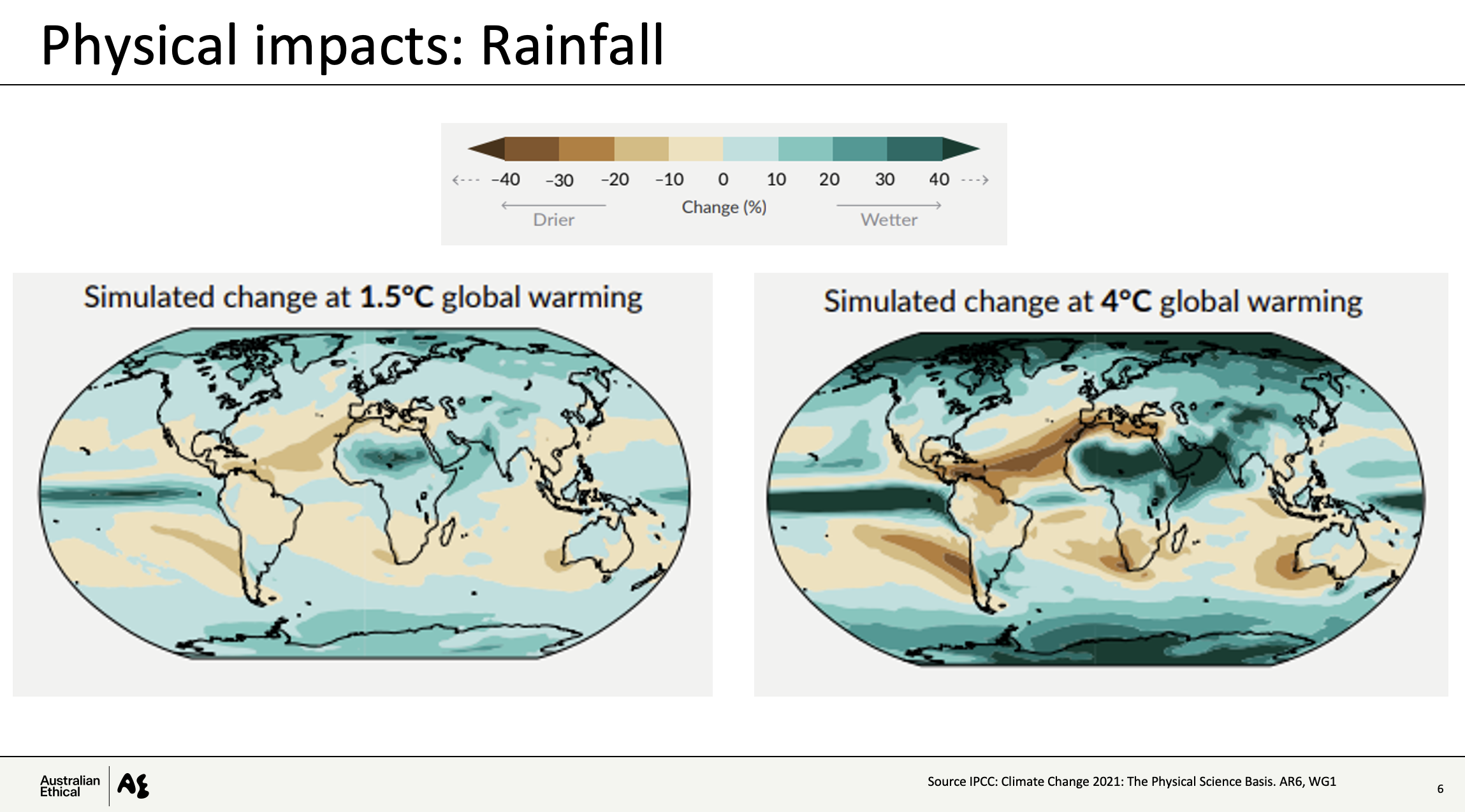

But even without strong climate policy and action, we’ve already seen massive low carbon innovation and investment which has dramatically reduced the costs and accelerated the takeup of low emissions technologies

Partly this is because companies and investors can see the inevitable climate driven shift away from high emissions energy and transport and from other high carbon technologies. Partly it’s because these are simply better, safer and cleaner technologies.

I’ve mentioned the IPCC climate reports, another key source of insight is analysis from the International Energy Agency, the IEA.

The IEA reported last year on what it will take to get to net zero emissions by 2050. Their net-zero emissions 2050 transition scenario.

No new coal mines, or coal mine extensions. No oil and gas exploration, only those new oil and gas projects already on the books.

They also investigated the other side of the coin, the new investment opportunities.

The IEA net zero scenario shows global clean energy investment rising from about US$1 trillion dollars to $4 trillion p.a. over the current decade.

The IEA talks about an “unparalleled clean energy investment boom”, which lifts global economic growth.

The IEA says the more than tripling in annual clean energy investment drives an increase in global GDP of 0.5% per annum to 2030, speeding the recovery from the COVID-19 shock.

Governments and companies listen to the IEA. The IEA has often been criticised as an establishment defender of the fossil fuel sector, so when they paint this sort of transformation, people pay attention.

So where’s the capital going this decade? It’s spread across more renewables, upgrading and expanding grid and other energy infrastructure, reducing energy demand through energy efficiency technologies. Two of their examples:

In 2030, annual new solar and wind energy capacity will be added at 4 times the current rate. Electric vehicles sales will be 18 X 2020 levels.

These are global numbers, EV sales in countries like Australia with a very low base can expect quicker EV growth. Countries with an advantage in renewables production, and with opportunities to leverage that production through technologies like green steel, like Australia again, can also expect renewables to grow more rapidly.

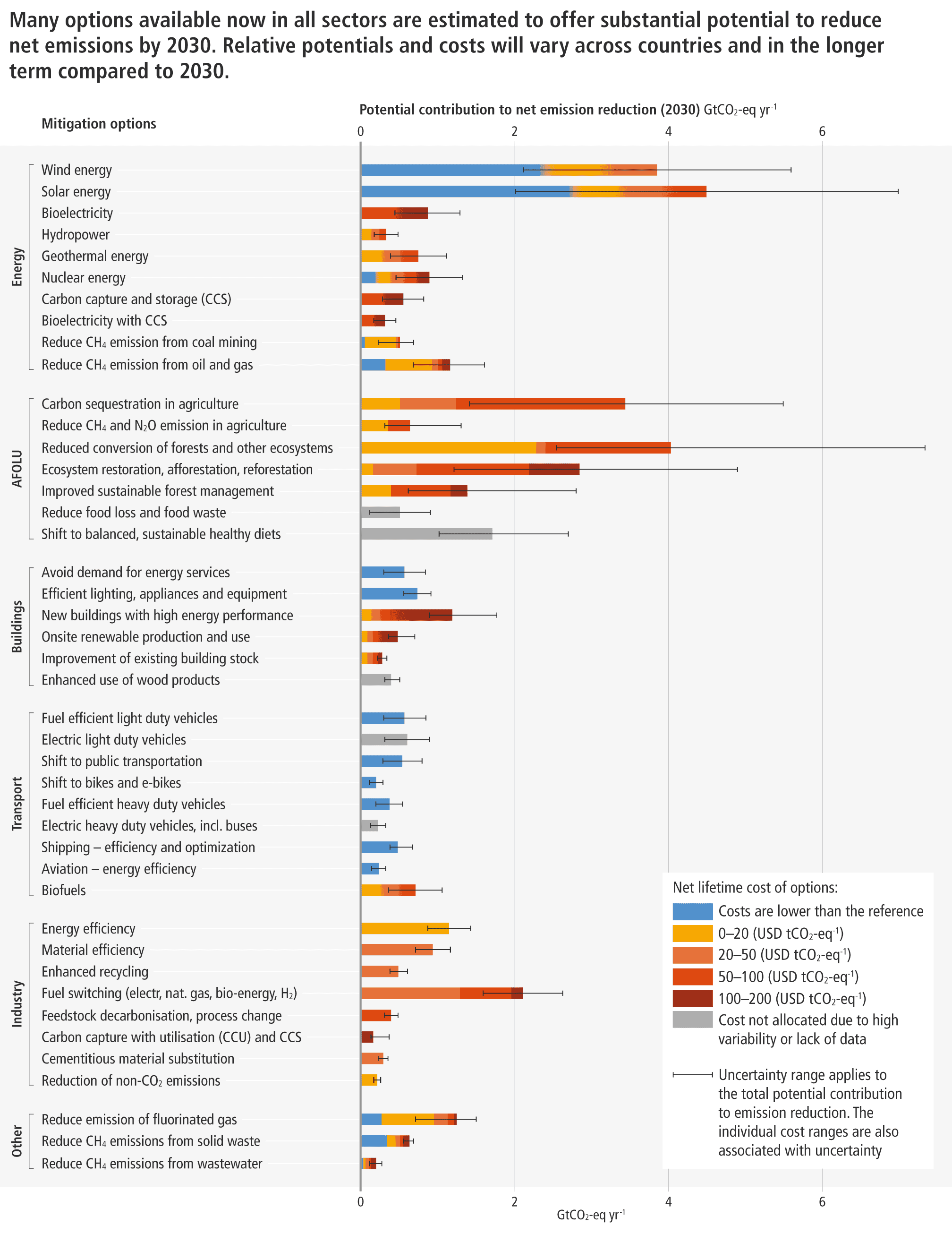

Source IPCC: Climate Change 2022: The Mitigation of Climate Change. AR6, WG3

The energy sector is crucial to decarbonization, but we will see transition and transformation across the economy.

The latest IPCC 2022 report identifies over 40 categories of decarbonization opportunity across not just energy but also agriculture, forestry, buildings, transport, and efficiency technologies which lower the demand for energy and materials:

- Ammonia and hydrogen-powered ships.

- Zero emissions steel produced using hydrogen.

- Concrete in our buildings and infrastructure which absorbs carbon.

- Direct capture of CO2 from the air.

And supporting all these changes, there will be fundamental changes in minerals demand. The IEA net-zero emissions 2050 scenario sees annual demand for decarbonisation minerals like lithium, graphite, copper and nickel increasing by five times over the period 2020 to 2050.

These are the minerals that will be essential to reengineering industrial processes and transport to allow electricity to replace other, hard to decarbonise, sources of energy.

Source IPCC: Climate Change 2022: The Mitigation of Climate Change. AR6, WG3

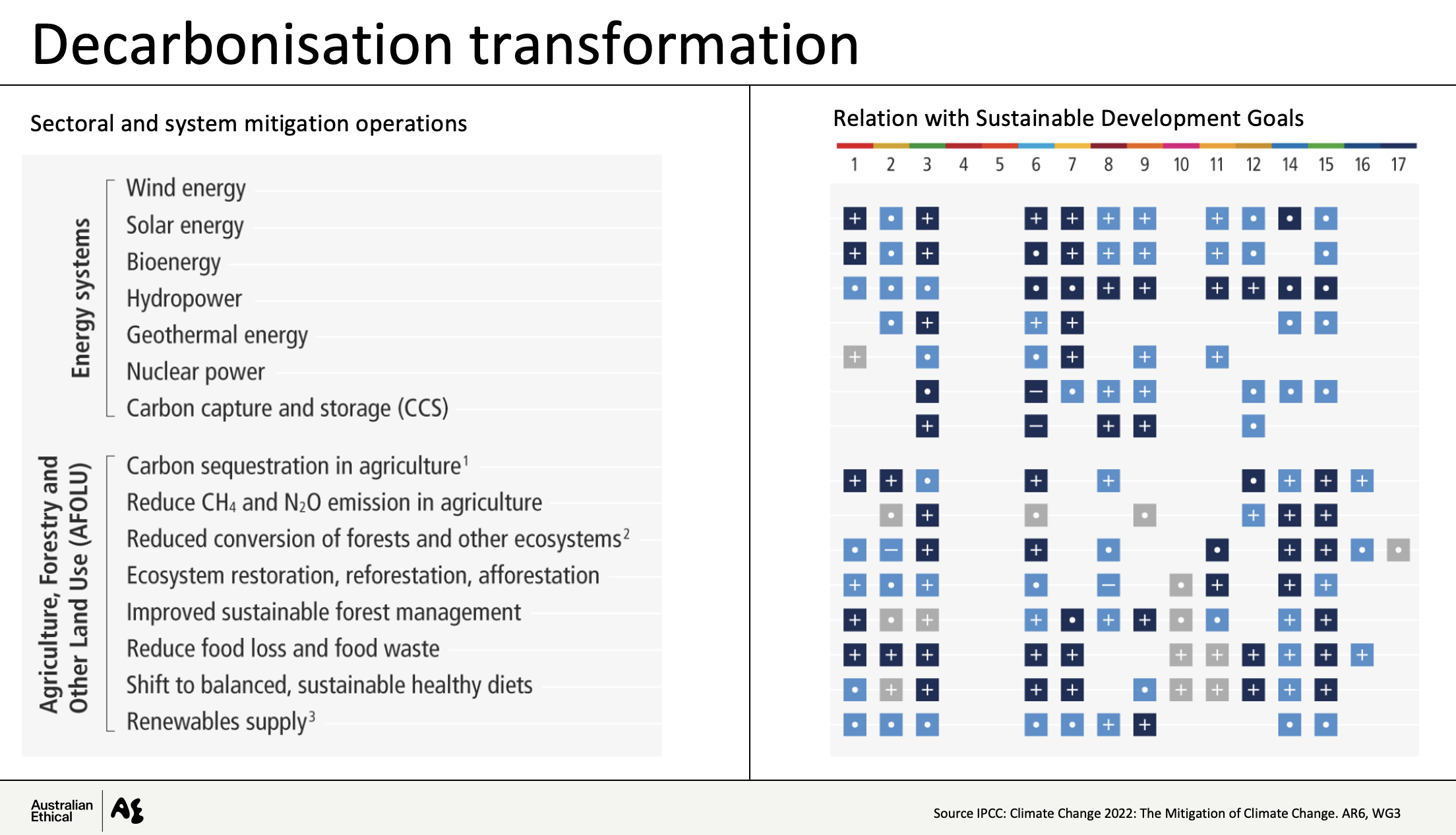

The decarbonisation transformation will be shaped by more than carbon and climate

With competing decarbonization technologies and pathways, the winners will be those which both reduce emissions and help address other local and global environmental and social challenges.

The latest IPCC report maps climate mitigation opportunities to the Sustainable Development Goals. These Sustainable Development Goals are 17 goals, 17 SDGs, which identify priority areas for global action to address crucial social and environmental challenges by 2030. As well as tackling climate change, the SDGs include goals to secure access to food, water and healthcare, reduce inequalities, support decent work and sustainable growth, safeguard biodiversity, promote peace, justice and strong institutions.

Some decarbonization options will be positively aligned with other SDGs, some will carry a higher risk of obstructing the achievement of other SDGs. For example:

- Fast-growing monocultures of eucalypt forests may be effective carbon sinks, but they can also harm biodiversity and harm local agricultural productivity and livelihoods, as well as local wildlife.

- Wind turbine development in Western Sahara in northern Africa can reduce energy emissions but it can also power unjust expropriation of natural resources by foreign powers.

- Conflict minerals meet growing demand from EV manufacturers, but at an unconscionable cost to the children forced to mine the cobalt.

These multiple dimensions of global need and demand increase the investment opportunity for companies and technologies which can positively address a number of these dimensions of impact.

A battery manufacturer, for example, with less resource-intensive battery technology; that sources materials from conflict-free mines; or that is influencing better labour practices in its supply chain.

The multiple dimensions of need, demand and impact also increase complexity – for companies, but in particular for investors who often have limited information about whether and how companies are really addressing these issues.

So we are seeing growing reporting expectations from investors – and from governments and regulators.

And in response, we are seeing much greater disclosure by companies about their ESG practices and impacts, about how they may be contributing to the SDGs. We’re also seeing specific reporting on corporate climate performance under the framework known as the TCFD – a reporting framework developed by the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

Now it’s fair to say this wave of new company reporting and disclosure is of very variable quality.

With stricter ESG and climate standards and expectations, more companies are talking a good climate game. The challenge for investors is working out which companies are walking that talk.

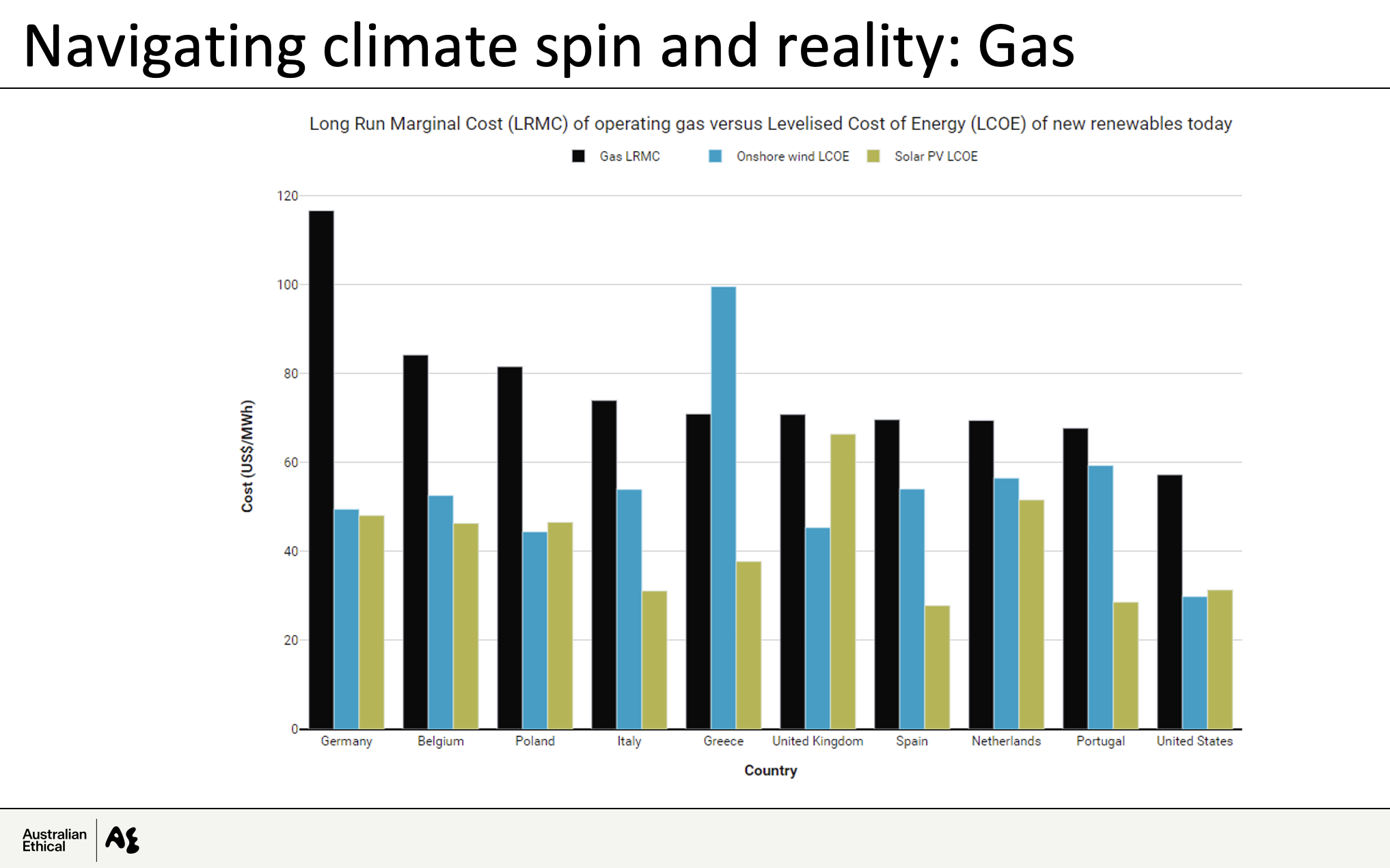

In Australia, we’ve moved on from the coal wars to the gas wars. Are we looking forward to a gas and LNG boom in Australia as gas plays an important role as a climate transition fuel, or do we follow the guidance of the IEAs net-zero emissions 2050 analysis which tells us gas investment and use need to fall over the current decade?

To further complicate the picture, we now have disruption of European gas supply entering the mix. This uncertainty will ultimately be resolved by markets and technology costs, combined with expanded government carbon pricing.

2021 Research by Carbon Tracker compared the cost of electricity from newly developed wind and solar to the marginal cost of electricity from existing gas generation. Across Europe and the USA, wind and solar are cheaper.

While new gas projects face climate-related risk, green hydrogen – hydrogen produced using renewables – has clear climate and geopolitical tailwinds.

Source: COAG Energy Council, Australia’s national hydrogen strategy, pg. 23, 2019.

But how strong are those tailwinds?

Hydrogen will undoubtedly play an important role in Australian and global decarbonisation, but the size of that role will depend on the different ways we end up using hydrogen fuel.

The stronger hydrogen demand scenarios will play out where hydrogen is adopted widely across transport, steel making and industrial and home heating.

The relatively lower demand scenarios are expected if we transition our infrastructure and industrial processes so we are able to meet almost all our energy needs from clean electricity. In those scenarios, we don’t end up needing hydrogen for things like heating and transport.

This uncertainty of hydrogen demand is compounded by competition between different hydrogen production technologies. Hydrogen made using electrolysers powered by renewables will be cheaper than hydrogen from fossil fuels, but that will require a big scale-up in renewables and electrolysers. We are now seeing companies and investors stepping up to fund that scale-up.

In the face of all this uncertainty and complexity, wise investors will not be jumping to simply invest in all things hydrogen-related, all things renewable, all things with a decarbonisation or climate-friendly label.

Alongside the risk of company greenwash, investors need to guard against "greenwish" – that’s the risk of over-stating the financial investment prospects of sectors and projects based only on their positive environmental impacts.

The best climate and investment outcomes will come from rigorous impact and investment analysis of the wave of decarbonization investment opportunities coming our way.

Let’s move on from the energy sector, important as it is.

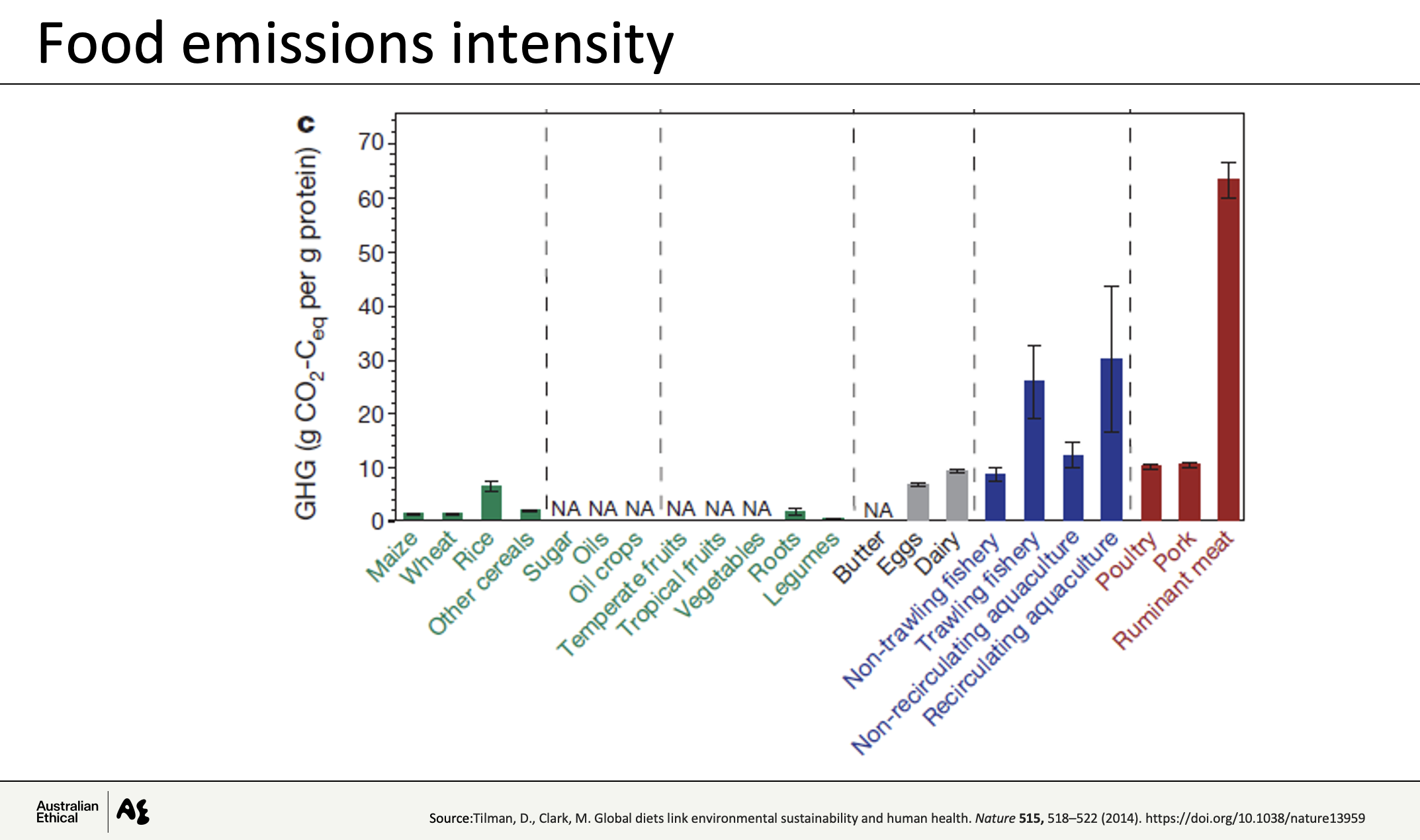

Source: Tilman, D., Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 515, 518–522 (2014). (VIEW LINK)

Food production contributes between about a quarter and a third of global emissions, and our food footprint will grow both with population growth and with shifts in diet to higher emissions food as more people adopt a western-style diet – if current trends continue.

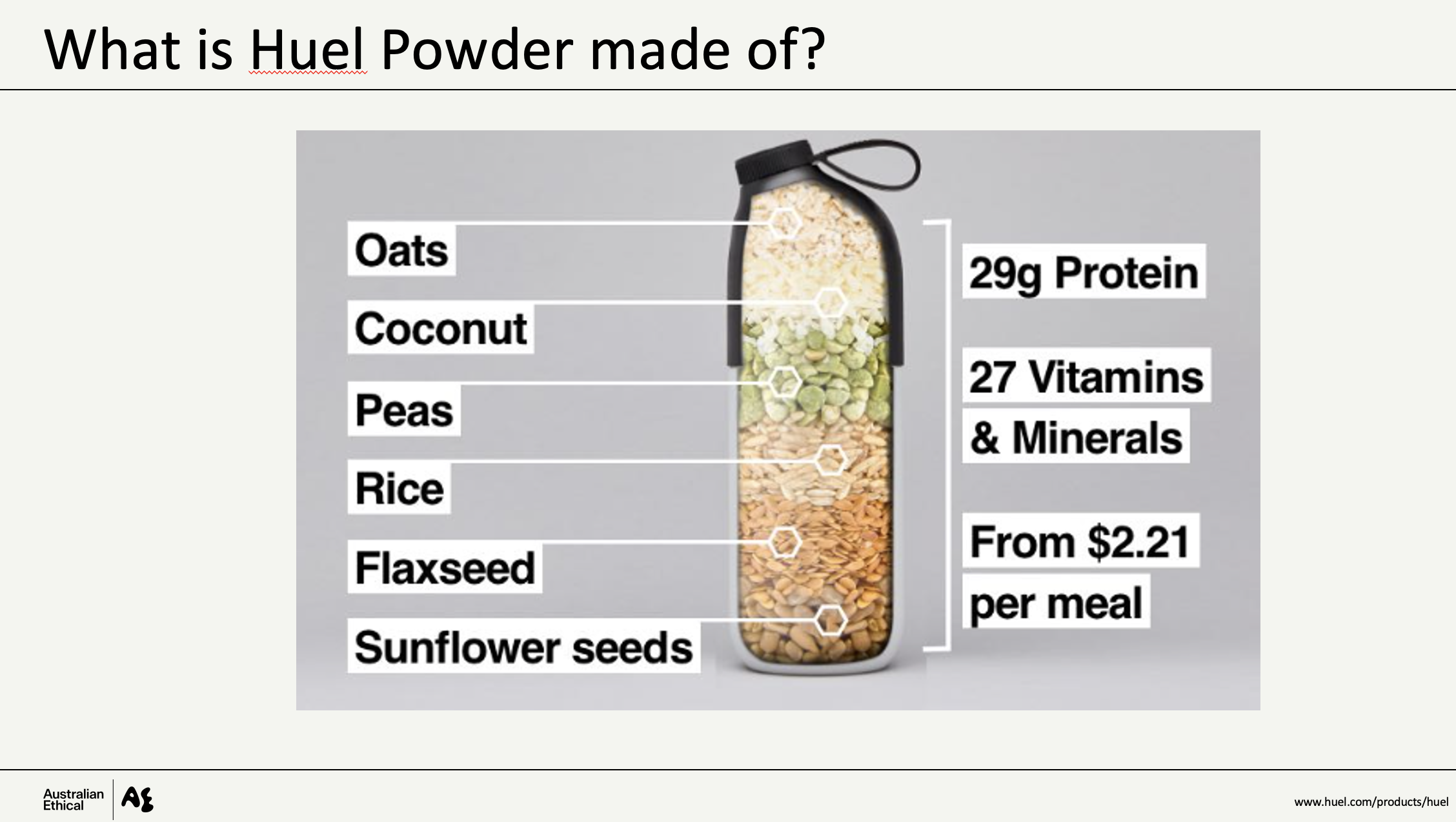

There are big differences in the emissions of different sources of protein and nutrition. Per gram of protein, red meat is on average over twenty times more emissions-intensive than plant-based sources of protein like nuts, soy and grains.

Agriculture has always been a complex sector for investors, it is now more complicated, and at the same time much more interesting.

It’s always been a challenging sector because of production uncertainty due to factors like weather variability and potential land degradation. And now weather variability and the risk of drought and flood are increasing with climate change.

But climate change also creates opportunities for farmers – for innovation in farming practices to improve efficiency and sustainability, for generation of additional income from carbon sequestration through land and soil regeneration, and for adjusting land use to take advantage of increasing demand for lower emissions sources of nutrition.

Shifts in the food sector raise interesting questions about the flexibility of our consumption habits.

Many of the opportunities for decarbonisation won’t change the day to day of many of us in Australia. They will for those in affected industries of course; and for those in countries where some of these new technologies might bring people safe and reliable energy for the first time.

But for most of us, green steel is still steel. Our lights shine the same with renewable or fossil fuel electricity. And getting from home to work with an EV is not too much different to driving a non-electric car.

So it’s interesting to think about some of the other changes to our world and lives which will be more personal.

Food and diet is often a hot button topic.

A nutritionally complete plant-based food powder as a replacement for our current diets isn’t going to excite most people (see above). Many people react negatively to plant-based meat, and to the prospect of lab-grown or cultured meat.

But it is important to think about potential climate-driven changes to day to day living, both as we think about investment, but also as we think about our own personal choices and lives.

This is important firstly because significant changes to our way of life are inevitable as the physical effects of a warmer climate increase. Secondly, because we may need more significant changes to our way of life to get to net zero emissions.

We know many of the technologies to get us there, but we don’t know all of them. We certainly don’t know in detail what decarbonization aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals looks like.

There is more than a risk, it is likely, that the technological solutions will not be enough by themselves.

Getting to net-zero and navigating the social and environmental fallout along the way will require more fundamental changes to our lifestyles. To what we consume. To how we reduce, reuse, repair, repurpose, recycle.

As well as using different building materials, we may build smaller houses. As well as different cars, we may use alternative forms of transport, we may use less transport altogether.

Beyond changes to our lifestyles, we may need changes to our news and social media, to the quality of our public debate, and changes to strengthen our democracies.

Taken all together these could translate into huge changes to our lives, our society and our economy. And they could be hugely positive changes for us and the planet if we make wise choices.

I’m optimistic about human capacity for change when change is needed. For all the harm it has caused, the pandemic has showcased our resilience and flexibility. How under constraint we’ve been able to work and live differently, and in some cases and in some ways to live better lives.

We will need to use that resilience and flexibility more than ever over the current decade and beyond.

Introducing Australian Ethical's first ETF

Australian Ethical started investing ethically in 1986. 36 years later, it is now easier than ever to invest ethically. Their first ETF, 'AEAE' gives you access to a focused basket of stocks from the S&P ASX 300, actively managed by their award-winning team from both an ethics and investment perspective. It is a High Conviction active ETF, giving you the added flexibility to buy or sell whenever you like.

1 topic

1 fund mentioned

Stuart evaluates the impacts which companies’ products, services and operations have on people, animals and the environment. He also contributes to our voice for more sustainable business and investment models and practices. Stuart has previously...

Stuart evaluates the impacts which companies’ products, services and operations have on people, animals and the environment. He also contributes to our voice for more sustainable business and investment models and practices. Stuart has previously...