Victoria raises $7.9bn from VicRoads sale for COVID debt repayments

There are media reports abound that Victoria has raised $7.9 billion from the partial sale of VicRoads. Treasurer Tim Pallas, confirms the funds will go to the state's new Future Fund that will be used to pay back the tens of billions of dollars of COVID-19 related debt that Victorian taxpayers have accumulated since 2020. According to The Australian:

[Pallas] said that the $7.9bn in upfront proceeds for the state would be invested in the new Victorian Future Fund to help manage its pandemic debt.

Victoria's debt issuance agency, TCV, today also announced that it had completed $14.1 billion of its FY23 funding task, leaving $15.8 billion of debt issuance for the remainder of the year. Following the budgets released by the five largest Australian States, we know that the official debt issuance task is going to be $75.6 billion for FY23, which is $10.1 billion less than the $85.7 billion task these States forecast for FY23 one year ago at the time of their FY22 budgets. (We had been expecting the task to be slashed materially.)

If one accounts for the amount of rapid-fire issuance the likes of NSW and Victoria have been able to do via their record floating-rate note deals, which have attracted $17 billion of bids from banks hungry for high quality liquid assets, the States' funding task for FY23 falls from the most recent budget estimate of $75.6 billion to just $65.6 billion. That is, the five largest States have exactly $10 billion less debt to issue in FY23 compared to their official numbers only a month or two ago.

Should we expect large pre-funding?

This in turn begs the question as to how much "pre-funding" the States will do. While it is commonly assumed that States will do significant pre-funding for FY24 as they finish FY23, the truth is that the hard data has not supported that proposition in recent years.

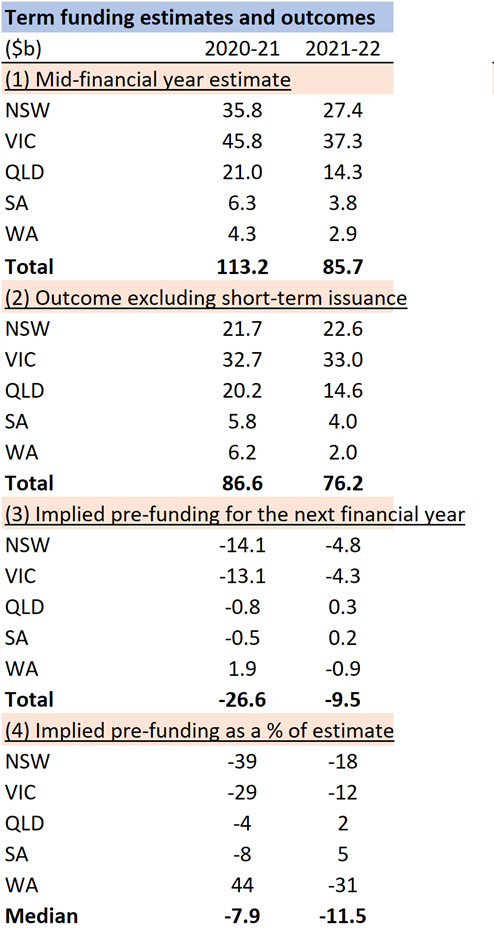

Our Credit Research Team examined the official debt issuance announcements of the States at their half-year updates for the last two financial years (ie, FY21 and FY22). They then looked at the actual completed funding. There were two noteworthy observations. First, the States tend to systematically issue less than their official announcements due to the fact that budgets usually overestimate capex spending and underestimate revenues.

The second thing they found was that the States have tended not to do any pre-funding at all over the last two financial years (Queensland and SA did a very modest amount in FY22 and WA did some in FY21). The table below summarises the results.

This is possibly due to the fact that the larger post-pandemic debt issuance programs make it inherently harder to get significant pre-funding done. As interest rates rise, the incentive to pre-fund may also be dissipating simply due to the very high cost of this debt.

The one exception here has been Victoria, where for the last two financial years TCV has claimed $11bn (FY22) and $9bn (FY23) of pre-funding even though actual issuance did not rationalise any pre-funding at all.

One alternative source of pre-funding is via the actual budget outcomes beating the budget forecasts. While this was a source of some pre-funding for Victoria, it does not come close to explaining the total sum of pre-funding that Victoria has officially claimed.

A final perhaps more likely explanation is that Victoria's funding task embeds pre-funding as a liquidity policy whereby the State automatically raises funding each year to cover debt maturities that arise 12 months ahead. This would mean that simply by issuing according to the official funding task Victoria concludes the financial year with nontrivial pre-funding already completed.

4 topics