What are carbon allowances, and why do they matter?

Key takeaways

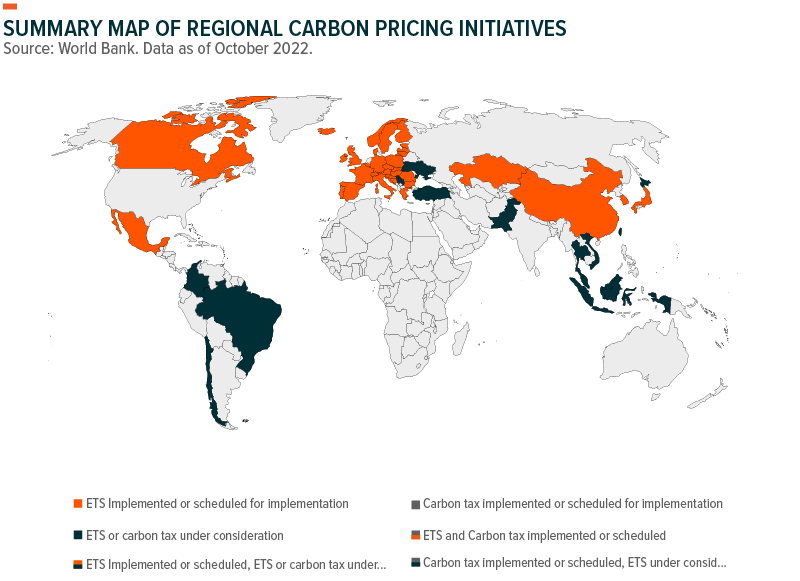

- Carbon allowances are growing in popularity around the world, as governments explore policies for bringing down greenhouse gas emissions.

- Thanks to futures markets, these carbon allowances are highly investible.

- Investment benefits can include diversification, potential price return, and the ability to have an environmental impact.

What are carbon allowances?

Carbon allowances – also called “emissions trading schemes”, or “cap and trade” – are sometimes described as the economist’s solution to greenhouse gas emissions. They are tradeable government permits that allow polluters to pump carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. Under these programmes, polluters must surrender enough allowances to cover their pollution upon inspection. Governments ensure compliance, with large fines issued for non-compliance.

Common Mistake: Carbon Allowances Are NOT Offsets

It should be noted at the outset that carbon allowances are NOT the same thing as carbon offsets. Carbon offsets, like the Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) issued by Australia’s Clean Energy Regulator, are unregulated voluntary programmes, where polluters do things like rent forests that theoretically offset their pollution. Offsets are sometimes marketed by companies to create “carbon neutral” products, like beef or plane flights. They have been criticised by academics.

Carbon allowances by contrast are mandatory and heavily regulated programmes that require emission to fall over time. Australia does not run a mandatory carbon allowance programme.

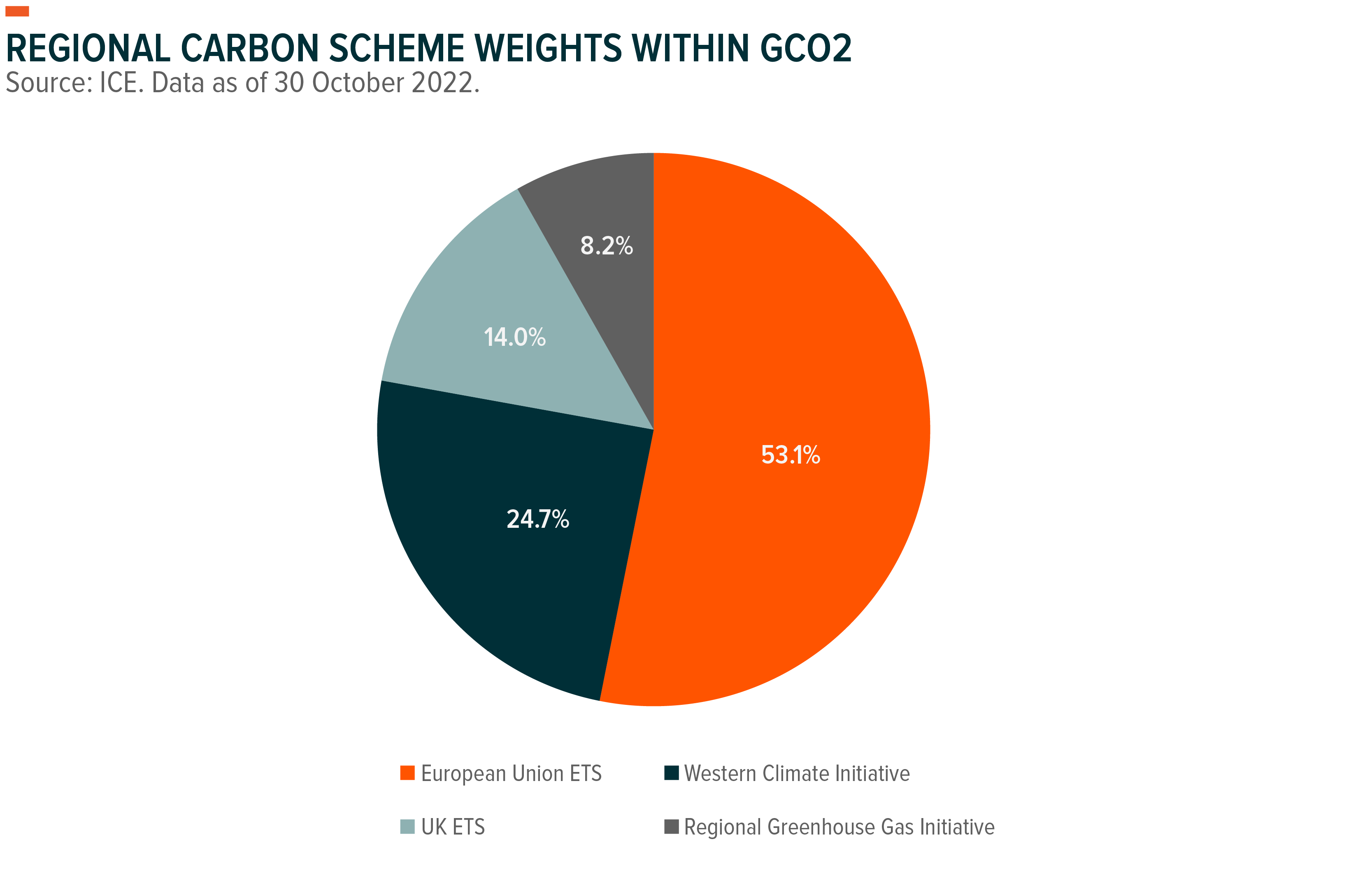

The rules governing carbon markets differ between countries. The European Union and the UK 1, which run the largest programmes, require all polluters above a certain size of emissions to participate. Examples of companies participating in the EU ETS include aircraft manufacturer Airbus, steel giant ArcelorMittal, Norwegian oil powerhouse Statoil, and the German carmakers BMW and Mercedez Benz.

California and Quebec – which work together to create the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) – require power plants and fossil fuel companies to participate. Participating companies include oil majors Chevron and Exxon Mobil, and the Canadian jet maker Bombardier.

While the north-eastern US states – which run the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) – require only power plants to participate. Participating companies in RGGI include Dominion Energy and the Carlyle Group, thanks to their ownership of fossil fuel power plants in New England.

Carbon allowances of various kinds cover roughly 17% of global greenhouse gasses, up from 5% in 2013. However, as China scales up the ambition of its own emission trading scheme, this number could soon be far larger.

How do carbon allowance markets work?

Carbon allowances are sold at auctions throughout the year by governments. Polluters – examples above – bid for them. If polluters use fewer allowances than they bought, they can sell the excess. If they go over their limit, they must buy more or face heavy fines. Financial institutions like hedge funds and banks can also participate in carbon trading if they wish. Trading of these allowances creates a market and ultimately a price for carbon, with the price varying between regions.

As years go by, governments shrink the supply of allowances they auction – and in some markets, outrightly increase the auction reserve price –making it more expensive for major polluters. Diminishing supply and rising prices encourage polluters to transition to clean energy – which requires no permits – and confers competitive advantages to companies with smaller carbon footprints.

Concrete example: the European Union’s ETS

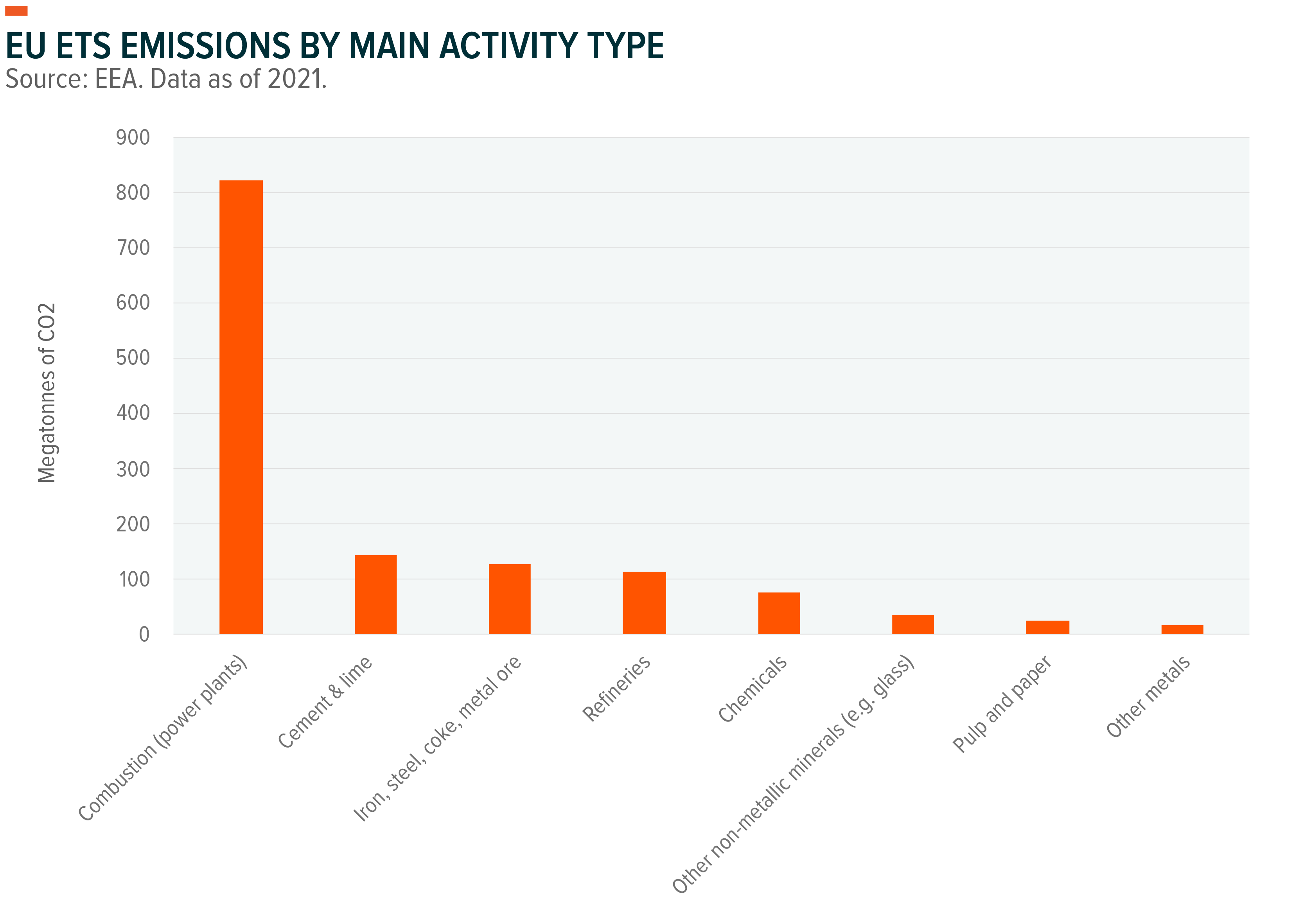

To give the EU’s carbon market as an example, the main group of companies that must buy carbon allowances are utilities companies that run coal-fired and gas turbine power plants. This is reflected in the graph below, which shows the biggest source of emissions is combustion of fossil fuels to generate electricity.

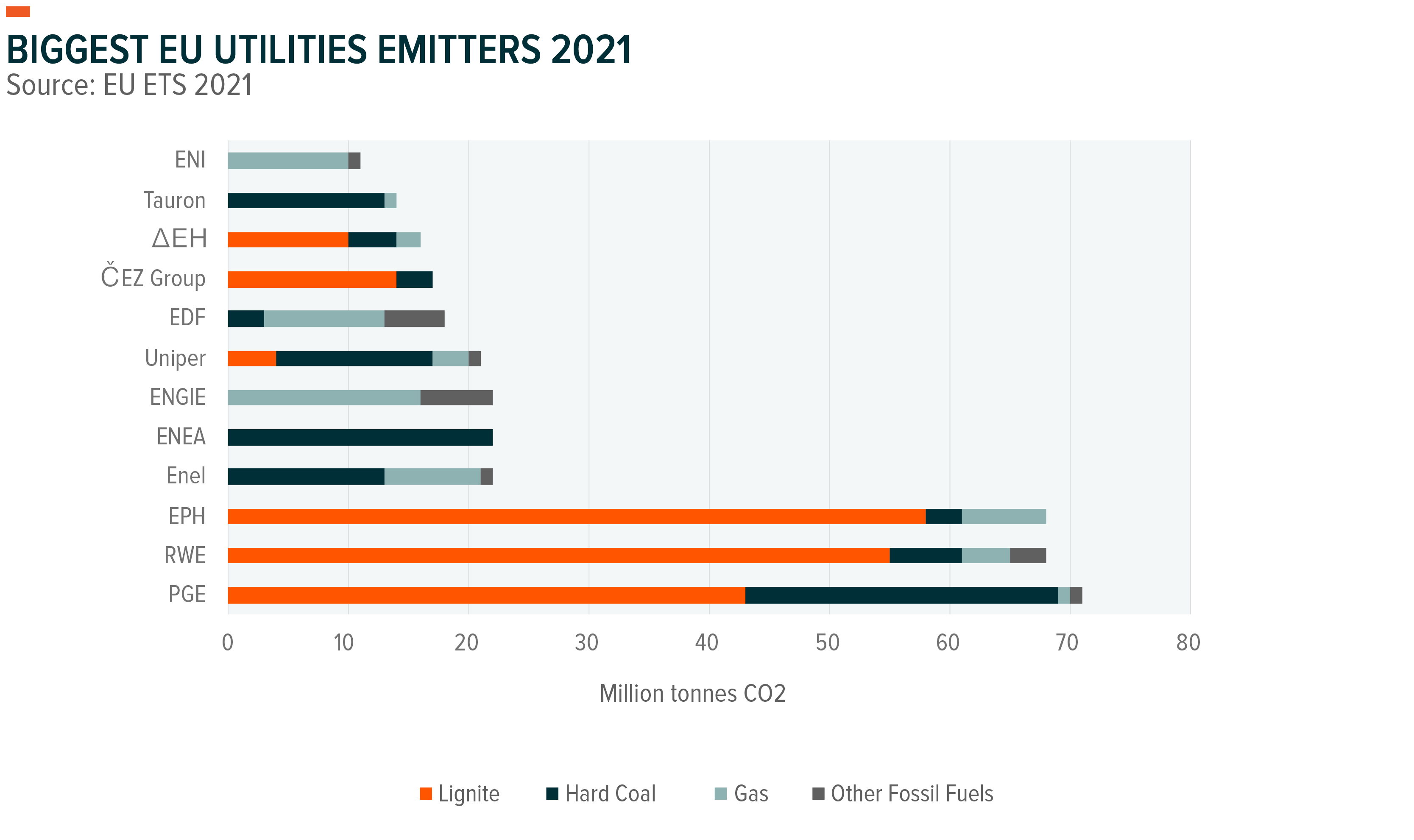

Looking at the next graph, we can then see which power plant operators are polluting more and why. The biggest emitters are the Polish energy giant PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna, Germany’s biggest utilities company RWE and Energetický a Průmyslový Holding (EPH), the Czech utilities conglomerate. As we can see, these companies have the largest carbon footprints because they combust lignite (also called “brown coal”).

The EU’s inspectors audit these companies’ power plants every year and come to best estimates of how much carbon dioxide they have emitted. These companies are then required to surrender enough carbon allowances to cover their emissions.

Investment thesis: Why are carbon allowances an investment opportunity?

The clean energy transition is a huge investment opportunity. Yet investors naturally wonder why carbon allowances are a good bet, rather than alternatives like battery technology, clean energy utilities or green bonds. Such curiosity is elevated by the strangeness of carbon allowances to many Australians and their common confusion with carbon offsets.

From our perspective, there are three major reasons for investing in carbon allowances: price appreciation, diversification, and environmental investing. We discuss each below.

Reason #1 – Potential price appreciation

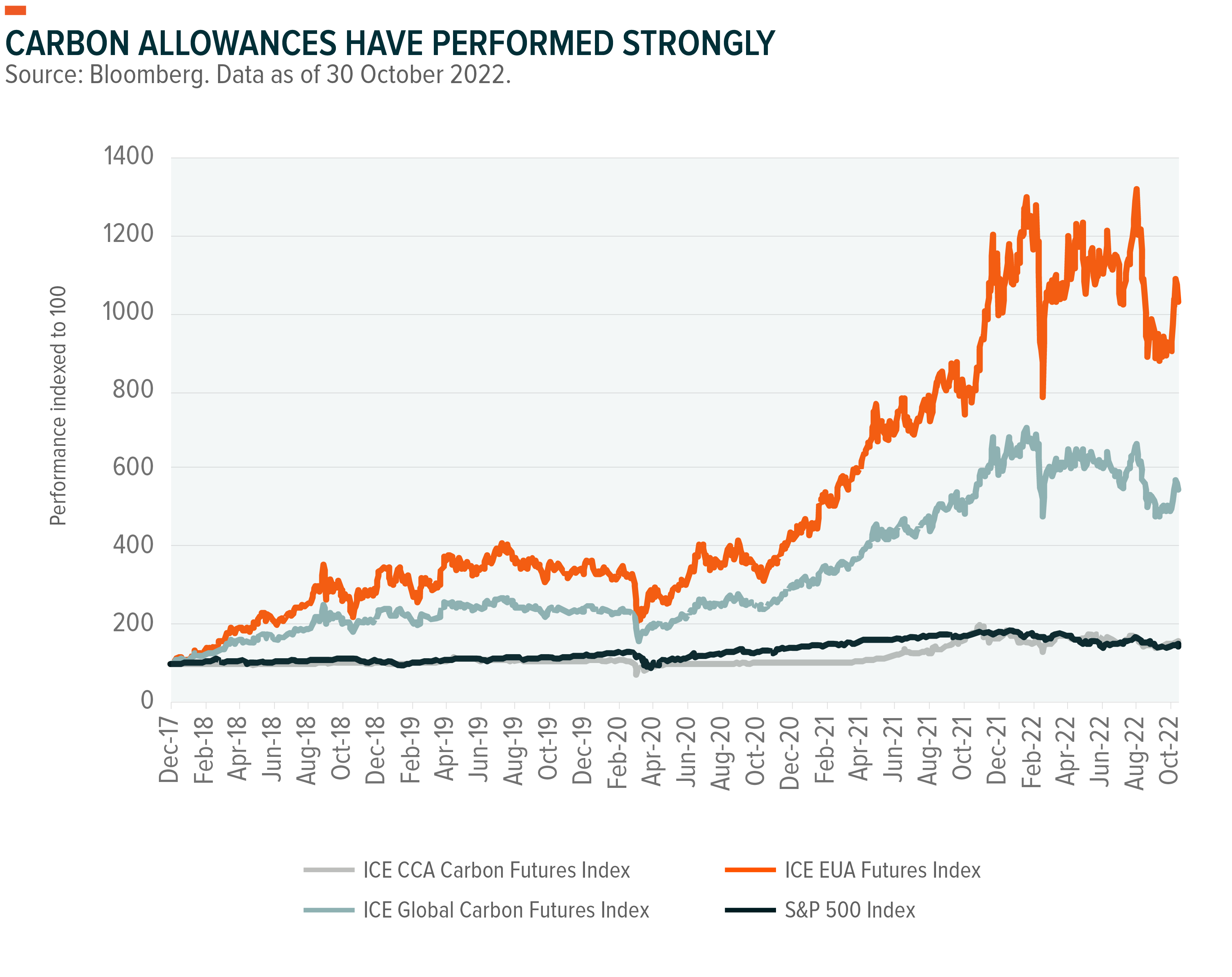

Carbon allowances have performed strongly in recent years, especially in Europe, the largest market. The ICE Global Carbon Futures Index delivered a 38.46% annualised return over five years from November 2017 – November 2022 in US dollars. While past performance does not guarantee future returns, the drivers of carbon’s historical return remain in place: supply, demand and government-mandated price increases.

The supply of carbon allowances in markets like the EU, UK, California and RGGI is designed to fall over time, with the shrinkage rate differing between regions. The European Union recently increased the speed at which supply shrank from 1.7% in 2020 to 2.2% in July 2021 under ‘Fit for 55’ legislation. 2 While the UK knocked an additional 5% of supply out of its market in 2021 as well. Economics textbooks teach us that, all things being equal, a commodity with a steadily diminishing supply should see its price increase.

Demand for carbon allowances is also, perhaps regrettably, rising. At the time of writing (December 2022) rising demand owes to sanctions on Russia straining global supplies of oil and gas. The absence of Russian fuel is causing the EU in particular to burn more coal. 3 Coal produces more carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour of electricity produced. Thus substituting coal for gas translates into greater demand for carbon allowances.

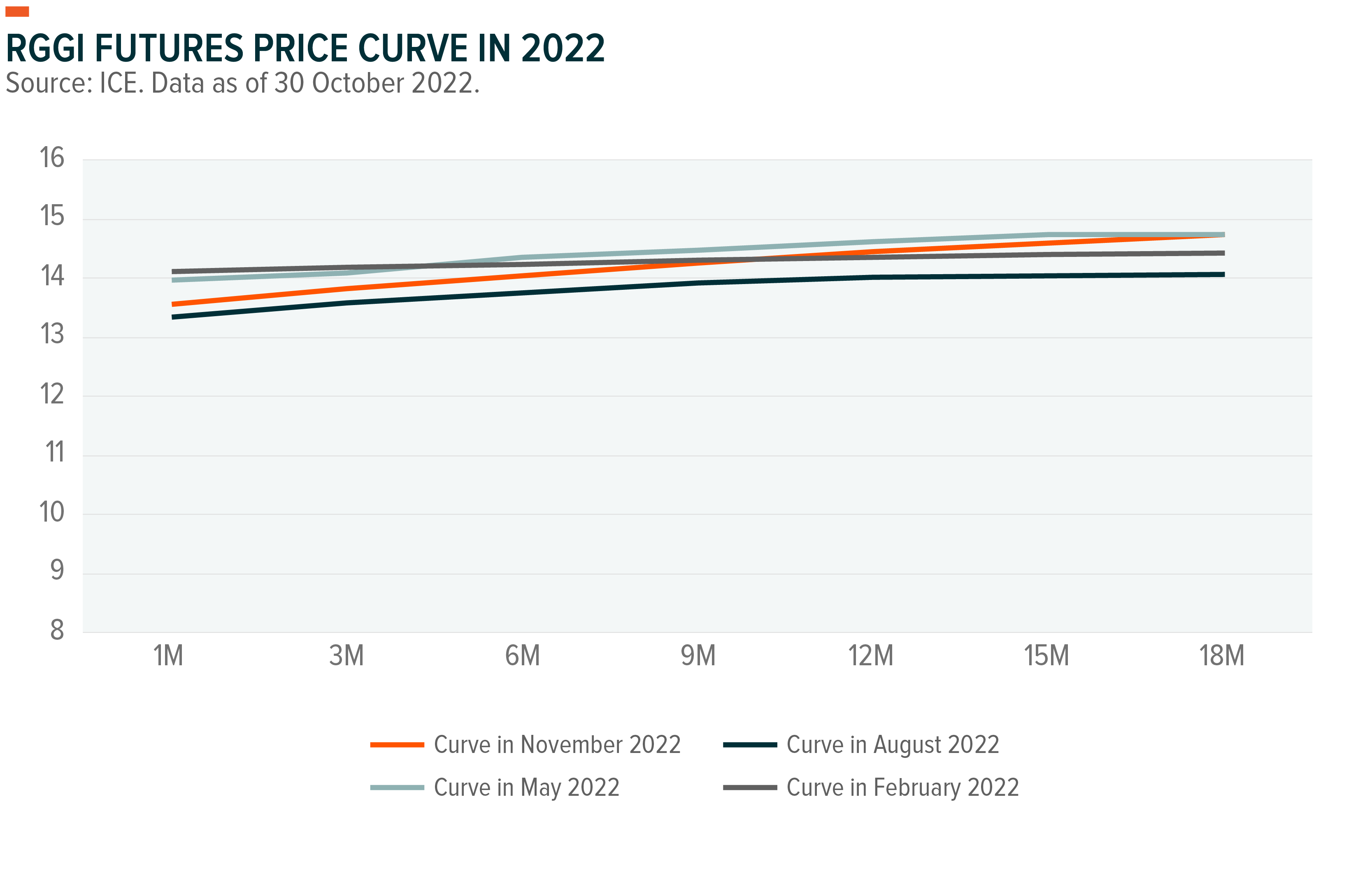

Governments are also engineering higher carbon prices in some markets. In the RGGI states and California, governments dial up auction reserve prices every year. In California, the auction reserve price increases by the rate of inflation + 5% each year. 4 While in RGGI it rises by 2.5% per year. 5 (While the EU and UK lack a price floor, regulators can intervene if the market is oversupplied).

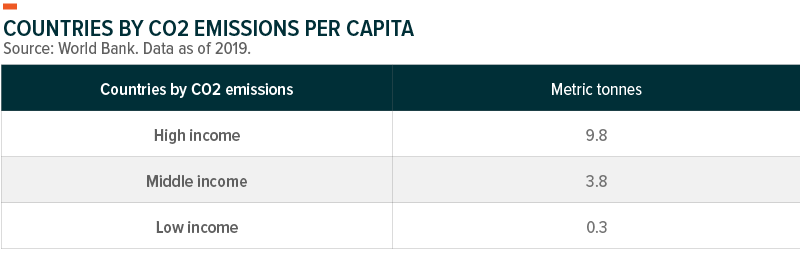

Beyond auction reserve prices, there is a sense in which higher carbon prices are existentially necessary. That is, if the world is to respond adequately to global warming, the price of carbon must rise to force down demand—in rich countries especially.

Richer countries have the highest greenhouse gas emissions per capita—and it is per capita emissions that ultimately matter most. Richer countries are also most able to afford clean energy alternatives, thereby ‘freeing up’ poorer countries to use cheaper fossil fuels.

It is perhaps worth noting how far carbon prices must rise if international agreements – like the Paris Accords – are to be honoured. According to the Real Carbon Index, the global weighted average price per tonne for countries with mandatory carbon markets is roughly US$23.70 as of 30 November 2022. 6 Yet academics suggest that global carbon prices need to rise to over $50 globally if we are to have a realistic chance of meeting climate targets. 7

Reason #2 – Diversification

Diversification is another potential benefit. Theory would lead us to expect that carbon allowances are poor diversifiers. This is because they are underpinned largely by energy demand—as discussed above in relation to Russia. And other assets – like utilities companies and oil – have similar underpinnings. But contrary to expectation, carbon allowances exhibit low correlations with other assets, including, crucially, the oil price (data below).

There are logical reasons for these low correlations. These include the fact that carbon allowances are a unique asset class, and exist only as digital entries in government ledgers. The fact that carbon markets are more centrally controlled by regulators than other financial markets, and regulations effecting carbon markets are much more idiosyncratic. And the presence of non-economic players – like governments – in carbon markets, which can give allowances away freely. Stock, bond, and commodity markets do not have such participants.

Reinforcing these diversification benefits for Australians is the fact that carbon allowances are issued overseas and not a regular feature in Australian portfolios, meaning their prices should not be directly tied to Australia’s economic outlook.

Reason #3 – Environmental investing without greenwash

Australian investors increasingly want to invest in positive environmental causes. After the 2020 bushfires, we saw a proliferation of environmentally marketed investment products. But amidst the scrum, investors have struggled to determine how environmentally friendly funds truly are. While ASIC has raised concerns that some investment products being peddled as environmentally friendly are not true to label.

An advantage of investing in carbon allowances is that its environmental credentials are clear-cut. They are expressly designed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. And in this respect, they are perhaps the only instruments of their kind.

Common question: Can buying carbon allowances force carbon prices higher?

Investors sometimes wonder whether buying carbon allowances can force up prices, thereby making pollution more expensive. And wonder whether carbon futures can be used for political activism. Conceptually, we would imagine that carbon futures can force carbon prices up. Carbon futures are deliverable, meaning that buying them translates directly into demand for carbon allowances. All things being equal, greater demand for a falling supply of allowances should cause prices to rise. However the European Central Bank has studied the role of speculation in carbon markets and concluded there is no good evidence at this stage that speculators are materially impacting carbon prices.

Carbon futures: Invest in carbon allowances

Investors looking to invest in carbon need a way to do so. While the obvious choice would be buying carbon allowances outright, carbon allowances do not trade on exchanges or on any single venue. Instead, carbon allowances are traded in different places and different ways, often bilaterally between institutions. They can only be traded by registered participants, which have accounts within government registers.

In this setting, futures are a common way investors access the carbon market. Carbon futures – unlike allowances – are traded on exchanges. These futures are often more liquid than allowances, and some of them trade hundreds of millions of dollars a day. They are primarily used by polluters looking to hedge, but they can also be used by investors wanting long term exposure or speculators. Exchange traded funds – including the Global X Global Carbon ETF (Synthetic) (ASX Code: GCO2) – use them to invest in the carbon market.

Potential limitations and risks

Contango

Investing in futures comes with the risk of contango. Contango is where futures trade above the spot prices of a commodity, and fall in value (relative to the spot price) as they come closer to maturity. Contango can reduce returns, as it requires investors to “sell low, buy high” when rolling futures contracts. Contango is common in many commodities futures markets – such as gold futures – as logistical and storage costs get priced in.

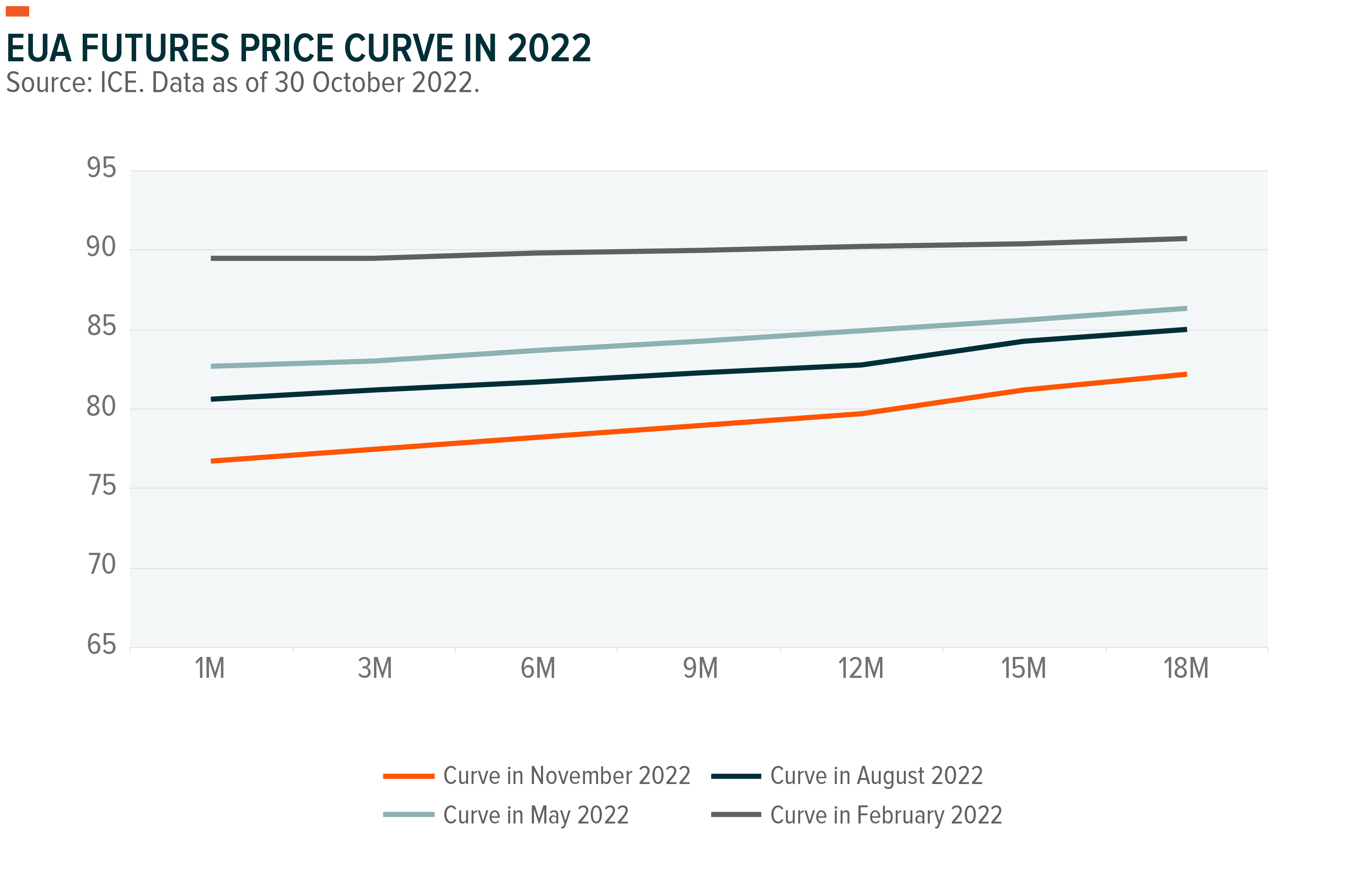

However, carbon allowances are digital entries in governments’ ledgers. As such, they do not carry the same logistical or storage costs as other commodities. Meaning that while there is often a small amount of contango in carbon futures markets, there is never a lot. The futures curves in carbon allowances have historically remained flat. This is particularly true in Europe, the largest market (pictured above, which shows the shape of the futures curve at various points in time).

Environmental inadequacy

Critics also question the environmental credentials of carbon allowances. They claim that current allowances are too generous to polluters, and insufficient to meet international agreements. Meanwhile others point to the opposite problem of “carbon leakage”: as only some countries and regions participate in emissions trading schemes, polluters can simply shop between jurisdictions to avoid the restrictions.

On these points, there are no easy answers. We would only note that evidence suggests that carbon allowances, in markets where they are used, are having their desired effect and bringing greenhouse gas emissions down. 8,9 And evidence suggests that carbon leakage is minimal, as carbon allowances mostly target utilities companies with immobile infrastructure and allowances are not prohibitively expensive for polluters. 10

Related funds

GCO2: For investors wishing to invest in carbon allowances, the Global X Global Carbon ETF (Synthetic) (GCO2) provides a solution. The fund tracks the ICE Global Carbon Futures Index, and invests in carbon

For GCO2, Global X is partnering with Carbon Neutral, a business specialising in reforestation, to plant and maintain trees in the Yarra Yarra biodiversity corridor in Western Australia. As part of this, Global X will contribute 10% of GCO2’s management fee each quarter to participate in Carbon Neutral’s Plant-a-Tree Program. The Plant-a-Tree Program is a reforestation project helping to reconnect small patches of remnant vegetation to create a 200km green corridor and protect plant and animal life. The fund is currently the lowest cost product of its kind in Australia.

2 topics