What are investment cycles and should you care?

Cycles are part of life. Whether it be the cycle of day and night, seasons, tides, weather cycles from the almost weekly cycles of cold fronts that regularly blow across southeast Australia to the longer La Nina and El Nino cycles, fertility cycles, birth and death, etc. And so, cycles are also endemic to economies and investment markets. Some are regular, some just rhyme.

Despite attempts to end or subdue them via economic policy and regulation the cycle lives on. Usually when we declare investment cycles dead they come back to bite us. Sometimes they bring much joy to investors but they can also bring much angst. But what are they? What causes them? And why do investors need to be aware of them?

Cycles within (investment) cycles

Cycles in investment markets invariably refer to swings between good and bad returns. They usually take their lead from fundamental economic/financial developments but tend to be magnified by waves of investor optimism and pessimism. There are three cycles of particular relevance to investors.

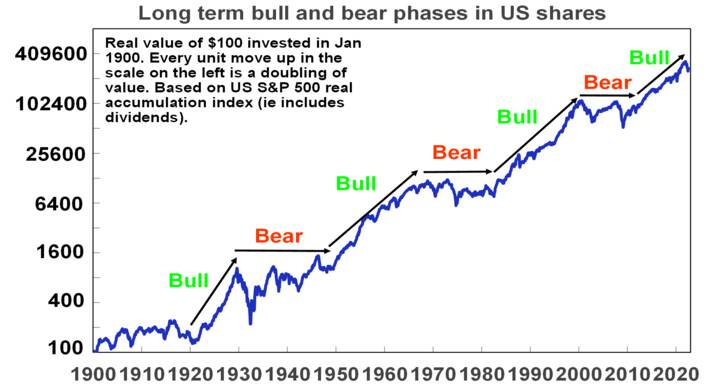

The long term or secular cycle - share markets go through long term or secular bull and bear phases, often lasting between 10 to 20 years. This is most clearly evident in the US share market and illustrated by the following chart. It shows the cumulative real value of $100 invested in 1900. Secular bull markets – or 10-20 year periods where the trend in shares is up – can be seen in the 1920s, 1950s and 60s, the 1980s and 90s and arguably over the past decade. In between in the 1930s and 1940s, 1970s and 2000s are secular bear markets – which are long periods where shares have poor and volatile returns.

Secular bull and bear phases are often related to what is known as Kondratiev waves, named after Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev who identified them and received the death penalty for his conclusions as they didn’t align with Stalin’s views.

Kondratiev waves take their lead from waves of technological innovation. Starting in the 1780s, water power, textiles and iron drove the first industrial revolution; steam, rail and steel drove the second industrial revolution; electricity, chemicals and the internal combustion engine drove a third Kondratiev wave into the 1920s; petro chemicals, electronics and aviation drove a fourth wave in the 1950s & 1960s; the IT revolution helped drive a fifth wave in the 1990s and another spurt more recently. These were associated with secular bull markets in the 1920s, the 1950s & 60s, the 1980s & 90s and over the last decade, although the move to ever lower interest rates & the search for yield & speculation it drove also played big roles in the last two.

At the end of each long-term upswing, share markets reached overvalued extremes and investors had become excessively exposed as optimism that good times would roll on forever reached extremes. This left shares vulnerable as excesses such as too much debt (1930s and 2000s), excessive inflation (1970s) and excessive speculation in tech shares and then housing in the late 1990s and 2000s became overwhelming, giving way to economic weakness and secular bear markets.

The business cycle – this is the best known economic cycle and has a duration of 3 to 5 years. It tends to relate to the standard economic cycle where after a few years of economic expansion, inflation or other imbalances build up which results in monetary tightening, which leads to a downturn or recession, then falling inflation and monetary easing, which then sets the scene for the next expansion. It tends to underpin a 3 to 5 year cycle in investment markets with the stylised link to share markets, property and government bonds shown in the next chart. Shares tend to lead the business cycle – bottoming several months before an economic trough and vice versa at the top. Property markets tend to be more coincident.

The standard 3 to 5 year investment cycle

.jpg)

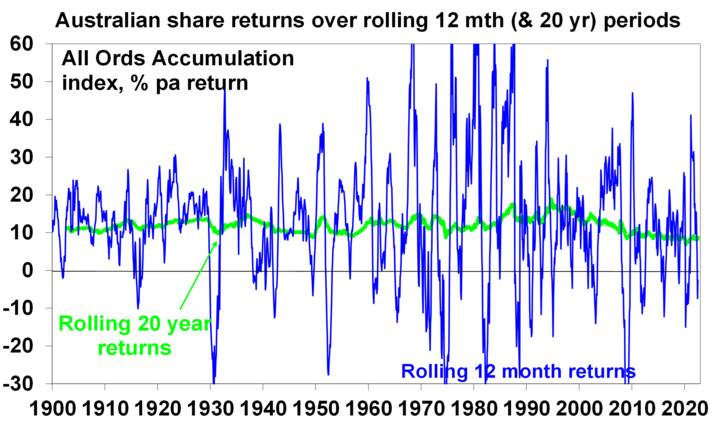

In terms of actual share market fluctuations, the 3-5 year investment cycle is evident in the swings in rolling 12 month changes in Australian share prices. Periods of poor returns are invariably followed by periods of strong returns (and vice versa) but trying to time this can be very hard. See the next chart.

.jpg)

Short term sentiment cycles – within the 3 to 5 year investment cycle there are also short-term swings (weekly, monthly) between overbought and oversold for things like shares and currencies driven by sentiment, but which can relate to the tendency for economic and profit data to run through hot and cold periods, particularly relative to market expectations. They often give rise to corrections in share markets.

Some observations

There are several points to note regarding investment cycles:

- No two cycles are the same but they do have common features, usually being set off by economic or financial developments accentuated by swings in investor sentiment. As such, while history doesn’t repeat, it rhymes.

- There are cycles within cycles. For example, even though US shares were in long-term secular bear markets in the 1970s and 2000s they still saw periodic investment cycle swings up and down in economies and share markets.

- When several cycles combine the impact can be huge. For example, a business cycle downturn in 2000 coincided with an end to the secular boom of the 1980s & 1990s and saw 50% falls in global shares in 2000 to 2003.

- Despite various attempts to smooth them out (via economic policies) or declare them dead, cycles live on.

- Cycles can be self-limiting as economic downturns lead to lower inventories, pent up demand and lower interest rates, which sow the seeds of recoveries. Share slumps result in cheap shares which entice bargain hunters and sow the seeds of a new bull market.

- Investment cycles provide opportunities for investors to vary their asset allocation through the cycle, eg, buying more shares into downturns and cutting exposure into upswings.

- But timing investment cycles is difficult. No one rings the bell at the top or bottom. And given the natural psychological tendency of individual investors to project recent market moves into the future and find safety in what the crowd of other investors are doing, the main risk is that investors, in seeking to time investment cycles, end up wrong footed by selling after big falls & buying after big gains. So, for most investors its important to be aware of cycles and understand that they are normal, but then to take a long-term approach to investing that looks through them and makes the most of the compounding of returns over long periods.

Where are we now?

The surge in inflation and aggressive monetary tightening by major central banks have knocked us into the downturn phase of the investment cycle.

Economic indicators have generally started to slow and recession is a high risk, with central banks continuing to raise interest rates.

US and global shares have already seen greater than 20% falls into their lows in June (and Australian shares fell 16%) and have since recovered just over a third of their decline.

It’s possible we have seen the low in shares (as they lead the economic cycle) but the risk of a resumption of the bear market is high given central banks are yet to stop raising rates and the risk of recession remains high, which would drive earnings downgrades.

The shift to higher inflation may see the US share market move into a weaker more volatile phase of its long-term investment cycle. Australian shares with their greater exposure to resources may be better placed in a longer-term context.

Other cycles of relevance

Political cycles – these are less relevant in countries with an irregular political cycle like Australia. However, the US has a precise four-year federal political cycle and this has given rise to a fairly regular pattern. This sees below average returns in the first two years after an election but well above average returns in the third year (as the President seeks to stimulate the economy to help his parties’ re-election), and to a lesser degree in the fourth year. Right now, we are in the second year which is known for sub-par returns – particularly prior to the mid-term elections. The US political cycle for share returns normally improves once the mid-terms are out of the way in November and as we move into the third year of the US presidential cycle.

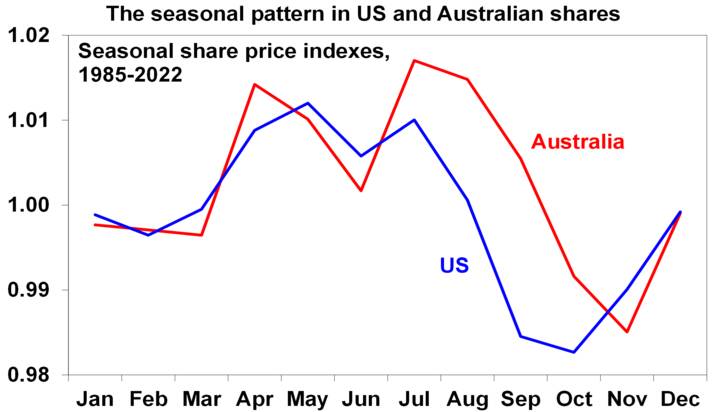

Seasonal patterns – There is also a well-known seasonal pattern in shares that sees strength from November reflecting the ending of US tax loss selling, a wind down in new equity raisings, new year cheer and the reinvestment of bonuses - continue after a brief pause around February into mid-year, before weakness from around May to October. Right now, we are in a period of seasonal weakness that runs into October.

.jpg)

Concluding comment

Being aware of investment cycles, and how they influence ones’ investment psychology, is of critical importance for investors.

3 topics