What’s behind the rise in house prices - and what to do about it

Dexus

There are many explanations for the astronomical rise in house prices along Australia’s eastern seaboard. But most economists settle on is that we haven’t built enough homes in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane to support their booming populations.

According to real estate consultancy firm Red23, lot sales in Melbourne are averaging a record 65 a day with more than 20,000 sales over the past 12 months. The rate of growth in the city’s population, however, indicates around 27,000 new homes are needed each year. No wonder house prices keep rising.

That poses a problem for investors and homebuyers alike. Housing affordability is at an all-time low; credit is becoming harder to obtain; and banks are pushing interest rates upwards out of cycle. Against that backdrop, it’s hard to imagine residential house prices performing as strongly as they have recently over coming years. What are investors to do?

Before explaining how to respond to recent price increases, it’s vital to understand how exceptional recent house price performance has been, and the factors that threaten future performance.

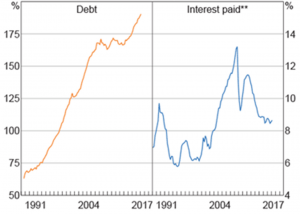

Sydney’s median house price now rests at around $856,000. Melbourne’s is not far behind at $655,000. According to CoreLogic, since January 2009 – the height of the GFC – the median dwelling price in Sydney has surged by 113.7%, outpacing Melbourne where prices have shot up by 101.4% over the same period.

Cumulative change in dwelling values from Jan 2009 to current (Post GFC growth)

Source: CoreLogic, August 2017

To some extent, such extraordinary price rises – remember that over the same period the US, Spain and Ireland were experiencing crashing property markets – were understandable, at least in Australia.

The country was enjoying a Chinese-led mining boom and government action to ameliorate the impact of the GFC was largely successful. The result was relatively easy access to credit and historically low interest rates. As the chart below shows, between September 2008 and September 2017, the RBA slashed the cash rate from 7.25% to 1.50%.

Graph of Cash Rate

Source: Reserve Bank Australia June 2017

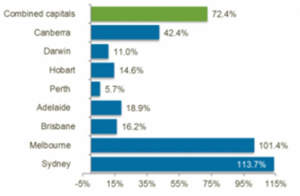

Australian households responded exactly as expected. They loaded up on debt. From 125% in 2004, the average household debt-to-income ratio has now increased to 190% (the comparable figure before the US crash in 2007 was about 140%). It is now one of the highest in the world.

The chart below, sourced from the RBA and ABS, compares household debt to the percentage of that debt consumed by interest payments. This is where it gets interesting. While debt as a percentage of income has increased since the GFC, the proportion paid in interest has actually fallen. That’s the impact of historically low rates at work.

Household Finances* Per cent of household disposable income

* Disposable income is after tax and before the deduction of interest payments

** Excludes unincorporated enterprises

Sources: ABS, RBA (Reserve Bank Australia June 2017)

The chart also points to the most obvious risk. With households more indebted than ever, the impact of rising rates could hit very hard. That risk is not reflected in the rewards of owning residential property, which has become a game of speculation.

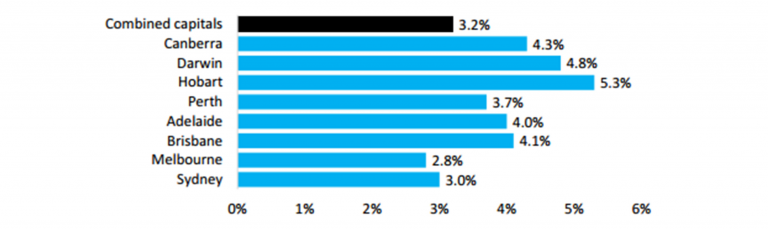

Gross rental yields currently sit at record low levels, hovering at around 3.0% in Sydney and 2.8% in Melbourne. After expenses, that’s no better than returns to cash, which means residential property investors are punting on future house price rise.

Current gross rental yields

Source: CoreLogic August 2017

In APN Property Group's view, this is not a sensible strategy. With household debt at record highs, wage growth flat and interest rates at record low, residential property investors are taking a bigger risk than many might acknowledge. Rates would not need to rise by much for many to start feeling the pinch.

So, what should property investors do?

The first thing is to manage your asset exposure. The 2014 ASX Survey showed that whilst only 1.8% of Australians own an Australian Real Estate Investment Trust (AREIT) or Listed Property Trust (LPT), more than one in five own a residential investment property. Having made good returns in the sector, residential property investors should check their asset allocation, ensuring they’re not over-exposed to the sector.

For those that are, a second issue arises – what should one do with the cash freed up from property asset sales? If you’re simply interested in locking in your gains, holding cash in a term deposit while waiting for attractive opportunities to come your way may suit your needs. If you’re looking for income, it might not be enough.

Property trusts known as AREITs invest in retail, office and industrial property, offering a diverse range of property classes from storage centres, childcare centres, petrol stations, retirement villages and even healthcare property assets. In many cases, they offer higher yields and more stable cashflows than can be expected from shares or residential property.

Not only is the risk/reward trade-off superior (due to the lower reliance on capital growth versus security of the rental income stream), but the liquidity and diversification, in addition to the lower ongoing costs, can make an AREIT investment attractive.

Either way, residential property investors should understand the risks they’re taking merely from holding assets that have appreciated markedly in price over the past few years. As we say in finance, past performance is not a guide to future returns. Don’t put yourself in a position where you have to find that out the hard way.

3 topics

Matthew is tasked with analysing and investing in Australian property trusts. He brings fundamental property knowledge, experience across a number of property sectors and a genuine interest in the AREIT sector.

Expertise

Matthew is tasked with analysing and investing in Australian property trusts. He brings fundamental property knowledge, experience across a number of property sectors and a genuine interest in the AREIT sector.