What the Federal election means for investors

JCP Investment Partners

The negative effects of ALP policies on housing, SMSFs and profit margins are already impacting certain sectors of the market, such as banks, residential property developers, homebuilders and retailers.

It is possible that if the ALP forms government in the 2H 2019, some more clearly defined fiscal policy may improve sentiment given markets will be anticipating fiscal stimulus to increase deficit spending with the aim of providing macro stability. In addition, it is likely that the RBA will begin the process of cutting rates (which are already priced in to forward rate markets).

In the background, the election is likely to be more important that headlines suggest. A change to the mandate for governing is as likely to change of the government itself, and post initial reservations may herald a stronger economy in the long-run.

We suspect that the slowdown already underway could be deeper than the market is pricing. Further housing weakness could impact on consumption, and given the transmission mechanisms through the economy, cause weakness in profits, capex, and employment.

The sharp fall in business confidence recently reflects these risks. Given the risks, fiscal stimulus is entirely necessary. Monetary policy is unlikely to provide enough stimulus given the cash rate is already low, whilst a weaker currency may provide a cushion, however not the significant boost needed to counter the risks faced.

ALP governments have a history of spending more on stimulus measures than Liberal governments.

Given fiscal stimulus is needed, that trend is likely to continue.

We expand on our views in this article.

Setting the scene...

The federal election in Australia is due to be held no later than 18 May 2019. It is the nature of the Australian political cycle that ALP governments tend to arrive in power at turning points in the economic and political landscape.

The rancour of the late ’60s led to Whitlam’s “It's Time”. The razor gang of Fraser struggling with the levers of the economy led to the Kelty / Hawke accord of the 1980s. And the arrival of the Rudd government in 2007 marked a point where the bargain of Howard’s battlers made way for a different style, at a point when the excesses of the 2000’s spending splurge were about to play out globally.

Elections like these, and perhaps the impending one, are points of inflection, but often only from the perspective of history. 2019 could be the same. We ask:

- Can Australia continue to endure flat real per capita economic outcomes without changing policies?

- Is it a nation in which the wealth of generations, and once off endowments can continue to be spent, without lifting productivity and engendering innovation?

- Can a jobs and growth mantra that fails to make the populace confident or happily endure?

- Is it a nation that can undertake a Royal Commission into the banking system, in which the basic safeguards to good lending can be laid bare, and then simply return to the same growth model?

We suspect not.

Unlike other parts of the world that have had their “populist events”, where nations have experienced sluggish recoveries from the GFC, Australia’s has powered ahead with a population driven growth model relying almost entirely on a narrative of household indebtedness, and the promise of government “surpluses”.

But this is a huge challenge – either new growth drivers are required, or at least a focus of growth that provides a different set of outcomes. The politics and policy issues that appear important in the foreground (franking credits, negative gearing), will present significant challenges to the mindset of the last decade, but will be mere precursors to a more important sets of changes.

Whilst the result is uncertain, the magnitude of the mandate and stability of the government will be critical.

Central to the emerging narrative post-election will be the economic background. Previous ALP governments have faced challenging conditions, the budget crisis of Whitlam, Hawke/Keating’s “banana republic” and “recession we had to have”, and GFC for Rudd/Swan.

In 2019, a slowing economy where a land boom is no longer the lifeblood of liquidity and money supply will be a challenge, but more so than the simple accounting of surpluses and deficits.

It has been a significant period since a government has sought to harness spending for economic stimulus, or to drive economic progress. Spending on education for social equity, or on the NDIS as a dividend of prosperity, or to support a low rate environment, will now need to pivot.

Expanding the economy into other areas that require complicated support is a factor that markets haven’t had to deal with for decades.

But the signposts for change are in place. Narratives that are likely to emerge will influence the economy, outcomes for the currencies and rates, and stock markets.

Such narratives could include the following:

1: The role of infrastructure as a social good that becomes a minimum condition for good government:

Infrastructure has the peculiar advantage of being both politically and economically expedient. The political success in Victoria, combined with the widespread disaffection for the spillover cost of record immigration will cement a range of infrastructure measures as core to the next government agenda. The long-term success / viability of many of these projects will remain unclear, but the medium-term economic benefit of “catch-up’ will be able to support nominal growth.

Companies directly engaged, those providing post-construction services (DOW, LLC, Cimic etc) and broader consumption will all benefit.

2: The removal of surplus targeting in budgets

A modern understanding of the economy makes it is very clear, the household sector cannot be undertaking balance sheet repair, at the same time as the public sector soaks up demand through surpluses. Breaking down this 25-year long obsession with surpluses could be the most important change that follows this election. In order to change this mindset however it will be critical that the initial focus of deficits be centred on “nation building” and measures that increase

confidence and social dividends. We believe stocks with exposure to the nominal economy; core staples expenditure and construction are best placed.

3: Clearer understanding of the role of nominal GDP targeting, government spending and inflation

Nominal GDP targeting is also a paradigm change but one which comes more naturally to government to than a pure growth model would otherwise appear and are ultimately more in tune with stock market outcomes. Governments raise taxation through nominal growth, domestic businesses generate nominal cash flow, and only the sceptre of inflation of 40 years ago.

4: Quality of life, especially as it relates to infrastructure, the environment, health and education

Quality of life and the intergenerational prism will be more than buzzwords in a slowing economy, as companies that appear to offer solutions to governments in this area will be rewarded. In the same manner in which emerging private hospitals provided solutions for governments in the 1990s, a range of new companies will emerge in the coming decade. Part of this focus will clearly be the environment. The precise way an ALP government tackles climate change could be an issue for later in the first term.

5: Equitable outcomes in the labour market

Labour outcomes – a range of otherwise unsustainable business models have emerged in the past decade, from 7-11 to some listed companies along with the challenges of Uber and Deliveroo. What is clear is that a number of listed players that are doing to the right thing are being disadvantaged by others that have exploited weakening conditions.

A strengthening of the labour market is likely to lead to higher wages growth, and the “unexpected’ collapse of a number of operating models. Intergenerational outcomes: what is the most effective response to community in which 65 percent of adults (up from 53 in 2013) believe their children with be worse off.

In combination, and in the long-term each of these narratives could support nominal growth, be positive for company cash flows and broader consumer spending. But the path to an alternative focus is likely to see dislocation, and a test of the political mettle of a new government. It is not clear that an ALP government will successfully drive change, unless faced with very weak conditions or an overwhelming mandate.

Markets when faced with future growth but short-term wariness will probably concentrate on the latter. But the old sources of comfort, such as domestic REIT’s or banking may not be as effective as companies with pricing power and broader exposure to the nominal economy.

Is change of this nature likely? 28 years of expanding economic conditions can belie the depth of analysis and momentum for change. The underlying movements towards the environment and social justice are arguably already progressed further than all political leaders entertain. The RBA, for instance, appears more likely to entertain alternative policy measures and scenarios. We would suggest policy options such as nominal income (GDP) targeting are scenarios that we must consider following the election, were a period of heightened economic tension to emerge. Regardless, the “Overton window” (the range of what is possible politically) has moved, the narrow focus on finance, monetary policy and empty growth is rapidly disappearing.

We see the post-election period as rewarding for investments in businesses which perform well when nominal growth is high and are likely directly supported by such policies.

The headline issues

The three most significant ALP policies that we believe could impact companies are:

1. The removal of refunds on franking credits, which will hurt high dividend paying stocks such as the banks, miners and Telstra, and;

2. Negative gearing and capital gains tax reductions for investment properties, which are likely to lower housing turnover and may lower house prices in an already weak market.

3. Health insurance premiums, a populist response to a poor value perception in the short-run but perhaps a driver for further reform?

Given the housing and consumer slowdown is already underway (with many of the negatives getting priced into assets (housing and equities) today), it is not surprising to see markets beginning to price in rate cuts by the RBA. An ALP government implementing these policies may observe the economy reaching the bottom of the cycle quicker, ensuring that stimulus is entirely necessary.

This point is critical – we believe that stimulus under an ALP government arrives faster and in a more direct manner than would be expected under a Coalition government. Stimulus will quickly be the story and its impact on rates markets conflicted.

On the one hand, it will provide policy support to the weakness in the economy, and on the other signal the “surplus paradigm” is at risk. On balance, this will be positive for markets.

The way in which the Trump election went from a negative to a positive for the stock market overnight, a similar outcome is possible in Australia in 2019.

This will be partly due to the enormous range of stimulus measures that a new government opens up, and will depend partly on the size of the mandate and the strength of the government formed (majority / Senate makeup etc.) Each of the narratives outlined before becomes a blueprint for change.

Were the Coalition to be returned, stimulus is still possible, but the mandate will be narrower, and the range of change more limited. In a period in which the old drivers of growth are questioned, the old stewards of that growth will not appear as strong.

Possible stimulatory policies to cushion the economy may include initiatives already on the ALP’s agenda, such as:

- stronger growth in renewable energy spending,

- high-speed rail, and

- reinvigoration of the National Broadband Network (NBN).

Some measures are likely to mirror the successful infrastructure initiatives implemented by the Victorian State Government, suggesting the “blueprint” for success is already in place. Tax cuts, targeting low to middle income earners are also on the agenda. Overall, the broad rebalancing of private consumption activity away from mortgage and credit card debt will be a focus.

The importance of stimulus (direct and indirect) is only accentuated by the emerging conditions in money markets, where support for rate cuts is not guaranteed to lead to positive outcome for consumers. Lower rates not being passed on due to higher funding costs, or households themselves reducing consumption in the face of high debt levels or reductions in wealth, is likely best assuaged by direct action.

ALP’s policies and what might this mean for markets generally and specific sectors

The ALP has made significant spending commitments on schools and hospitals as well as offering an income tax cut for millions of workers, surpassing the government’s tax offset. To achieve this, the ALP is proposing tax hikes including changes to dividend imputation, negative gearing, capital gains tax and family trusts, which if fully implemented would raise $A158bn over 10 years.

Removal of Refunds on Franking Credits

The ALP has announced that, if elected, it will reform the dividend imputation credit system, removing cash refunds for excess franking credits. Under the ALP’s proposal, from 1 July 2019, the imputation system would be restored to what existed prior to changes made in 2001 (i.e. any excess imputation credits would no longer be paid as a cash refund).

Under the ALP’s proposal, imputation credits (i.e. when the corporate pays tax & distributes a dividend) for individuals & superannuation funds can still be used to reduce tax, but no longer obtain cash refunds. Companies may pay out excess credits prior to any new legislation being implemented.

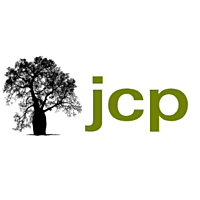

This measure, if implemented, would likely impact individuals on low taxable incomes receiving franked dividends and SMSFs. The ALP’s proposed franking ‘scale-back’ also makes the near term return of excess franking credits more attractive. The chart below ranks the franking balances of companies relative to market capitalisation in the ASX200. Among the large caps, BHP and RIO have already announced off-market buybacks. The recent reporting season saw distributions being a key theme. Dividends increased by 4.3% (June 2019 DPS) and an additional $3.5bn of new buybacks were announced.

Franking balance as a share of Market Cap

Source: UBS

In terms of a changing narrative, the Franking Credit debate is likely to prove very important. In time, the concept that an individual can arrange their finances in order to collect a tax refund when no tax has been paid by the individual will appear strange.

Negative Gearing

The ALP also plans to limit negative gearing to new housing after the next election, with the effective date to be determined. All investments made prior to the effective date will not be affected by this change and will be grandfathered. Losses from new investments in shares and existing properties can still be used to offset investment income tax liabilities. These losses can also continue to be carried forward to offset the final capital gain on the investment.

The proposed change to negative gearing is likely to weigh on both housing turnover and result in lower prices, which will impact property developers, online portals and banks. The grandfathering of negative gearing could reduce housing turnover further as investors choose to hold their properties in order to retain access to negative gearing.

We sense that these reforms will ultimately be good for the broader economy, because they will help to minimise the flow of capital into an unproductive sector and the impact on house prices should be less given investor participation in the housing market has already retraced. This is critical, the neo-liberal orthodoxy which simply presumed capital found the right home, and the benefits “trickled down” to the broader populace is now rejected, in style if not substance. But what replaces it, what sectors of the economy receive support going forward, in the same way as the real estate sector has done for the past decade is critical.

Capital Gains Tax

The ALP also plans to halve the capital gains discount, from 50% to 25%, for all assets purchased after a yet to be determined date after the next election. This will reduce the capital gains tax discount for assets that are held longer than 12 months. All investments made before this date will not be affected by this change and will be grandfathered.

This policy is likely to lower housing turnover and may lower house prices in an already weak market.

We suspect that this change will be a “sleeper’, just as its introduction in 2000 only created a ripple of interest, it quickly built to be a critical component of the supersonic growth in house prices in the following 15 years. The economics of the change are clear, large and grow through time, and ultimately feed directly into a discussion between the merits of taxing wealth at different rates to labour income, earned versus unearned income. Changes to capital gains tax will therefore be a critical signpost of the scope and appetite for reform.

Income tax

A 0.5% increase in the Medicare Levy for individuals earning more than $87,000, and (permanent re-introduction of) 2% Deficit Repair Levy for individuals earning more than $180,000 has been proposed.

For an economy already experiencing little wage growth and weak consumption, a reduction in after tax income for households is likely to further impact the retail and housing sectors.

Tax rises and their impact on consumption is likely to be more than offset by other changes. Targeting government support through earned tax credits, changes to benefits and support through government programs and investment would vastly outweigh the negatives of tax reform that concentrated on higher incomes. The short-term impact to sentiment that surrounds major budget changes in the 1st year of a new government will need to be watched warily.

Immigration

Concerns about the level of immigration and the associated rapid growth in Australia’s population, with its impact on congestion and housing affordability in the larger cities, have been raised by members of both major Parties.

The Morrison government has been more vocal on achieving lower rates of immigration in recent times in response to public concerns. The ALP has indicated a leaning towards modest cuts with an emphasis on the mixture of migrants and cost of entry.

Possible policy changes include improving the integrity of the transition of temporary visa holders to permanent residents and tighter eligibility criteria in specific visa and migration categories. But any such changes are unlikely to have significant impacts on economic growth or create significant upward pressure on wages.

Given population growth has been the “go to card” for consecutive governments to help boost GDP growth (unfortunately not GDP growth per capita), we suspect any change in immigration to be modest.

Industrial Relations:

An ALP government would probably seek to swing some workplace rights back to employees and organised labour that were lost under the WorkChoices regime of the current government. This may result in an expected increase in unit labour costs over time. The ultimate impact of higher labour costs will be felt through the success of generating nominal growth, and the structural support for business that aren’t exploiting workers.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure spending has been a strong source of growth in the economy and while the ALP has not committed to specific infrastructure spending targets, it has indicated it will fund targeted national programmes across a wide range of transport sectors and will establish a high speed rail planning authority.

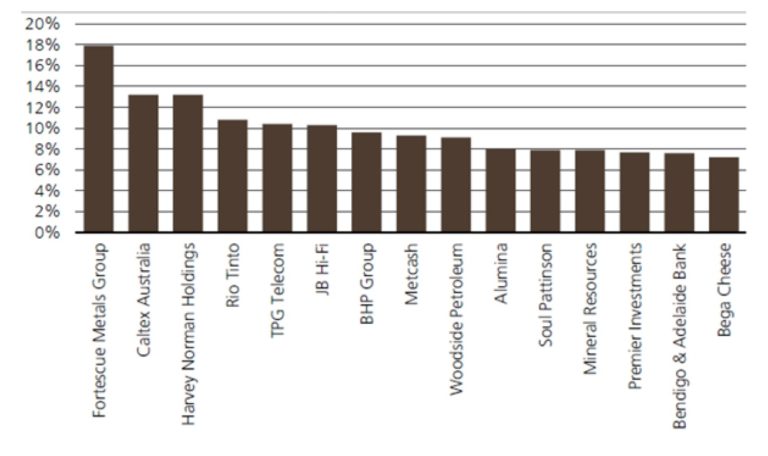

Initiatives may look to mirror the success implemented by the Victorian State Government, suggesting the “blueprint” for success is already in place. A chart in the 2018/19 Victorian Budget, a budget which was titled “Getting things done”, shows the clear focus on infrastructure spending.

Victorian Government spending on infrastructure

Source: Department of Treasury and Finance

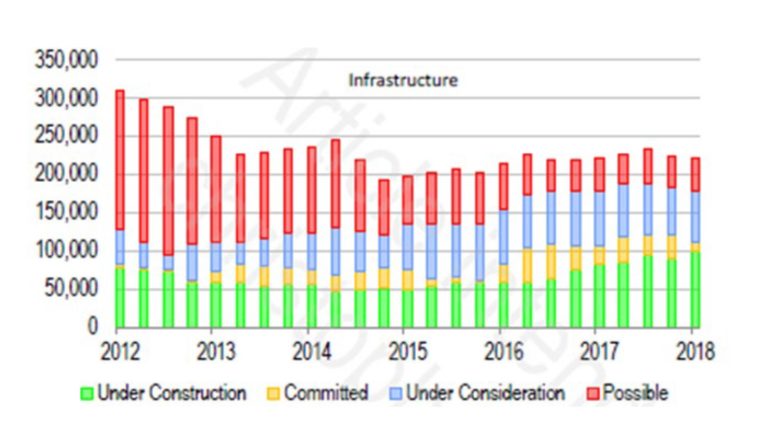

The ALP also supports the role of Infrastructure Australia in providing independent and expert advice on specific projects and supports innovative approaches to financing projects, including PPPs and superannuation fund investments. This suggests that infrastructure spending will remain at relatively high and possibly rising levels relative to GDP, however as illustrated in the chart below, the current infrastructure pipeline needs replenishment.

Infrastructure project pipeline

Source: Credit Suisse

Health Insurance

The ALP has committed to constraining private health insurance premium increases to 2% p.a. for 2 years for the next round of premium rate filings. This will place pressure on margins for NHF and MPL. The role of private health insurance, and its large public subsidies will be an interesting example of the competing interests of “quality of life’ and genuine opportunity cost of funding.

We see a tremendous opportunity for the industry to extend its social franchise beyond service provision into a sector that support the goals of government (transparency, price discovery and value for money). Whether the industry responds to such movements will be critical when faced with an ALP government.

Energy

The ALP’s proposed energy policy has a number of potential impacts. A target of 50% power from renewable sources (currently c.16%) by 2030 is aspirational, implying 1,500-2,000MW (around $3-$4bn) of new generation every year during the 2020s. While the mechanism to support such investment is yet to be detailed, we cannot rule out early closures of existing coals plants, or the re-introduction of a price on carbon emissions.

Labour has also suggested it may re-introduce the Turnbull Government’s National Energy Guarantee (NEG), which had previously been estimated to reduce household power bills by up to $550 pa, whilst also lowering costs for large industrial power customers.

The ALP’s energy policy also proposes a national interest test on new natural gas developments. We presume this test would make exporting gas reserves as LNG more difficult, but with domestic prices already largely linked to export pricing, the impact on gas producers may be limited.

NBN as an example of priorities

A likely write-down of the NBN, will be both symbolically important as well as possibly transformative to the sector. Key public infrastructure investment has rarely “paid for itself’ in an accounting sense, and in an economic sense is clearly “sunk”. Overpaying for such an asset once sunk adds little value to an economy, instead a significant write-down of the investment will unlock demand otherwise priced out.

The written down asset will release a consumer surplus as high-speed internet becomes more affordable. The critical impact on the industry will be the degree of innovation (product and price) and competition that emerges post downgrade. If as suggested the write-down is accompanied by additional investment in the network the spill over benefits to the economy and innovation could be substantial at best, and supportive of the nominal economy at worst.

As such, both the quantum of the write down (and hence surplus released) and the scale of the reinvestment will be another important signpost of change by an incoming government.

We suspect An ALP government is both more likely to write-down the NBN more heavily along with investment more in the NBN’s capacity.

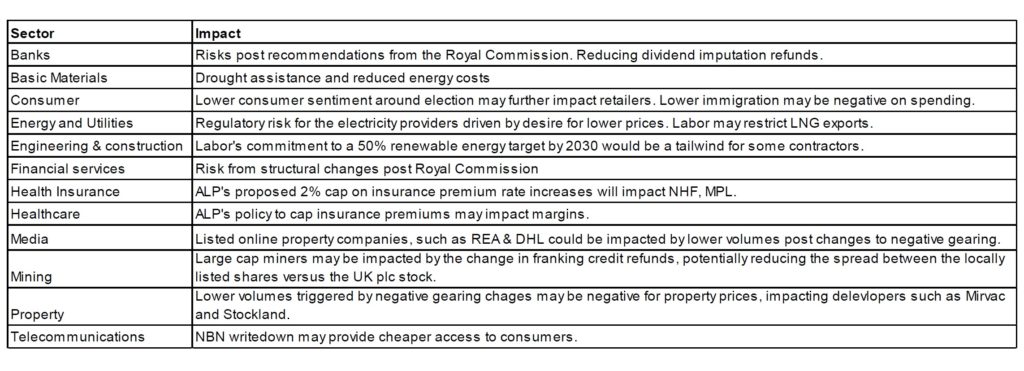

Impact on markets / sectors

To summarise the ALP policies, we see the risk of an ALP election victory impacting the economy in the following ways:

- Some further downside risk to house prices (negative gearing);

- More regulation of the labour market, and a likely rise in minimum wages/penalty rates; and

- Margin pressure, as wages rise and firms’ ability to raise prices is limited by cost of living focus and enhanced focus on competition and regulation.

The broad impacts on markets are likely to include:

- Lower AUD/USD, as the market reprices the return on real assets (housing, equities)

- Greater reliance on fiscal policy relative to monetary policy

- Volatility in the equity market due to heavier regulation, lower profits and more sovereign risk.

The table below lists some broad impacts across various sectors should some of the above policies be implemented upon the ALP taking up government.

The most quantifiable impact is the removal of franking credit refunds. BHP and RIO trade at a premium on the ASX over the London Stock Exchange which may reduce. Moreover, the bank valuations could be impacted with changes in franking.

The pathway forward – Is stimulus the answer?

There are enormous challenges ahead for which ever party wins the next election:

Growth in China is slowing – given their need for deleveraging. Australia’s term of trade is unlikely to provide strong national income growth, meaning the economy will be more reliant on other sectors and productivity growth to deliver improvements in living standards.

Royal Commission (RC) – in the wake of the RC, credit growth is slowing, and house prices are declining. The RBA does not have many interest rate cuts at its disposal to respond. The financial sector will be under heavy regulatory scrutiny and ongoing margin pressure post the RC, leaving capex (both private and public) and some growth in net exports, as the primary drivers of GDP growth ahead.

Household consumption will likely be capped – as financial constraints start to impact the household sector.

Fiscal response?

From a fiscal perspective, the government is on track for its forecast return to surplus by June 2020 given better commodity price outcomes in 2018. But with risks building in China, commodity prices are likely to decline over 2019 and beyond, requiring budget improvement to be more reliant on other sources of income growth. The recent growth forecast downgrade by the RBA in its February Statement on Monetary Policy (Year to 2Q 2019 has been slashed to 2.5% from 3.25%) reflects these challenges. Early data suggests even these forecasts are too optimistic.

With Australian GDP growth less dependent upon credit, housing and the consumer, the growth outlook in 2019 and beyond appears dependent on the global backdrop, as well as private and public capex spend. Recent data points to the challenges ahead; with construction volumes falling -3.1% qoq (vs consensus +0.5%), showing broad based weakness across states and sectors, demonstrating that the peak impulse to GDP is now clearly behind us. The extent to which a change in government can influence this trajectory will be important for the overall growth outlook.

It’s not surprising to see business confidence falling given the above challenges and uncertainty over which party wins the next election. As the economy heads in to the 2H of 2019, the risk is the economy will likely be navigating the bottom of the cycle, with policy stimulus entirely necessary.

Both history and circumstances suggest Australia is well placed for an ALP-style spending plan.

The ALP has plans for spending on renewable energy (clean energy and storage), infrastructure (invest more in road and high-speed rail) and telecommunications (re-invest to upgrade the NBN). Via directing fiscal stimulus outside the housing sector, the ALP will attempt to rebalance spending in the economy, such that it is less dependent on house prices and indebtedness. For the household sector specifically, the ALP is likely to offer more generous tax cuts and subsidies targeting lower income earners, who typically have the highest propensity to spend, which will hopefully provide a boost to consumption.

9 topics

7 stocks mentioned

JCP is a research-driven, fundamental Australian Equities investment manager. With almost 20 years of organisational experience we have a proven performance record in both bull and bear markets.

Expertise

JCP is a research-driven, fundamental Australian Equities investment manager. With almost 20 years of organisational experience we have a proven performance record in both bull and bear markets.