Which sectors will outperform as the 'Titanic' slowly turns post-COVID

Signs continue to indicate that inflation is creeping into the system. Central and global banks don’t tend to agree, but we think the tone will shift.

In the face of a constant inflation rhetoric, the global consensus continues to push back on the structural shift in inflation. However, evidence of price inflation and supply chain disruptions are now showing up at every corner.

- Volvo has slashed the size of its IPO in the face of soaring energy costs and persistent supply chain delays

- Nike’s first quarter sales missed Wall Street expectations by 7% due to production and shipping delays

- Swiss food giant Nestle has increased prices in 2021 and will increase prices a further 2% in the final quarter and in 2022 to offset input costs of more than 4%

- Unilever, which sells more than 400 brands into around 190 countries, announced that it will be raising prices of all its goods by 4.1% in the third quarter to pass on higher production costs

- The price

for durum wheat, the key ingredient in

pasta, is up 60% this year

-

Delta Airlines just

logged its steepest one-day drop (6%) in a year, after warning that

rising fuel costs could lead to an operating loss this quarter despite a

lift in travel demand.

The US Federal Reserve still sees inflation as temporary, with upticks in inflation explained away as simply the economy normalising after the pandemic shock and supply chain bottlenecks causing temporary disruption. But our US contacts note that those bottlenecks could last until 2022 or later.

US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg suggested in a recent interview that US supply chain issues may last "years and years".

Both Dubai Ports and Singapore-based Ocean Network Express, which carries more than 6% of the world’s containerised freight, have suggested an easing in supply chain disruption may not come until as late as 2023.

Watching the key metrics

Let’s take a look at what prices have been doing in the key categories of food, energy and wages.

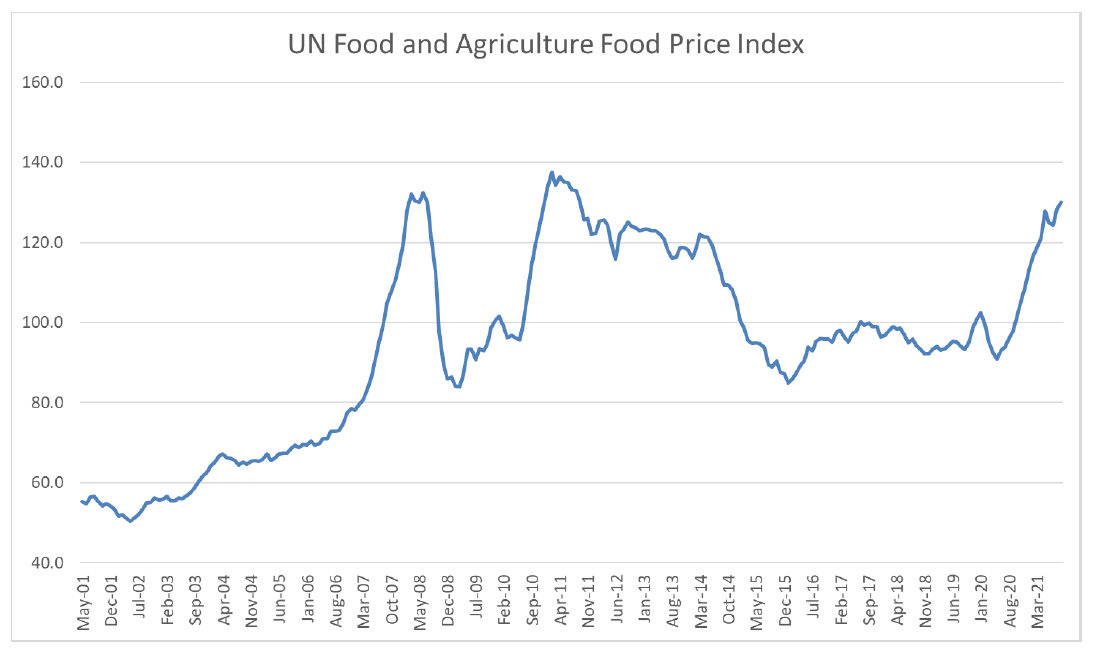

The UN’s Food Price Index is up 33% year on year. The index measures the global monthly price change in a basket of five food commodities, with vegetable oils up 61%, sugar up 53%, cereals up 27%, meat up 26% and dairy up 15%.

Rising fears about supply and energy security have also pushed Brent to above US$80/bbl, up 40%, and spot Asian LNG prices to US$35mmbtu, up 600% since 2019.

Source: Refinitiv, Jarden

Meanwhile, the USA labour market is already tightening. The drop in unemployment to 4.8%, and rapid 0.6% month on month wage growth, is indicative of a structural shortage of workers.

We expect the US experience to be repeated in Australia as our two largest economies emerge from lockdowns.

We’re paying close attention to wage inflation in this country, given the Reserve Bank of Australia has indicated it is unlikely to raise interest rates while this metric remains subdued.

Is history repeating itself?

If higher inflation becomes entrenched, like turning the Titanic, it takes time to reverse. We saw this phenomenon in the late 1970s, when three Fed chairmen tried to stuff the genie back into the bottle — with only Paul Volcker, the last of the three, delivering the silver bullet.

We believe what we’re seeing today is remarkably similar to the experience in the 1970s. Back then, food and energy supply shocks led the decade’s inflationary surprises.

First, bad weather saw CPI for food up 20% in 1973 and 12% in 1974; then came the Middle East conflict in 1973, which drove a rapid spike in the oil price.

History may not repeat itself, but it can rhyme. Today it is fuel prices, unfavourable weather and the impact of coronavirus on supply chains leading to food inflation.

For the oil market, it’s the rapid move towards ‘green’ renewable energy (coupled with strong demand as the world emerges from the ravages of coronavirus) and freight costs that has led to a 70% surge in global oil prices this year.

Why does it matter?

In the 1970s, inflation had a critical effect on pushing rates higher, further entrenching inflationary expectations. According to the RBA, the three-month bank bill rate was 6.6% in 1971 and 9.3% in 1974, which then jumped to 16.2% by early 1982.

Today, as inflationary pressures continue to build, several advanced economies have already increased rates, including the Norges Bank, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Monetary Authority of Singapore, with the Bank of England potentially moving shortly.

The recent Australian quarterly CPI release (3.0% year on year) has ensured that inflation will remain a heated debate into 2022.

At the very least: if inflation expectations build, interest rates launch sooner and bond prices continue to fall, then we should expect higher volatility in equities. Individual sector returns will diverge with winners and losers.

Equity returns historically beat inflation, within which commodities and energy sectors tend to do well. Banks and sectors which exhibit monopolistic pricing powers and hard assets, such as property, also perform strongly; whereas rate-sensitive sectors such as IT and loss-making stocks tend to underperform.

We have seen this before and have positioned the Kardinia portfolio accordingly.

Building and protecting wealth

Kardinia, a Bennelong Funds Management boutique, aims to generate positive returns through an investment cycle and not lose money in falling markets. For more insights from Kardinia Capital, click the 'FOLLOW' button below or visit our website.

3 topics

1 contributor mentioned