Why Australian 10-year yields may struggle to rally even as the recession rolls in

In the ‘year of the bond’ the beleaguered bond investor could be forgiven for being sceptical of the sustainability of any rally as we head into the final stage of 2023.

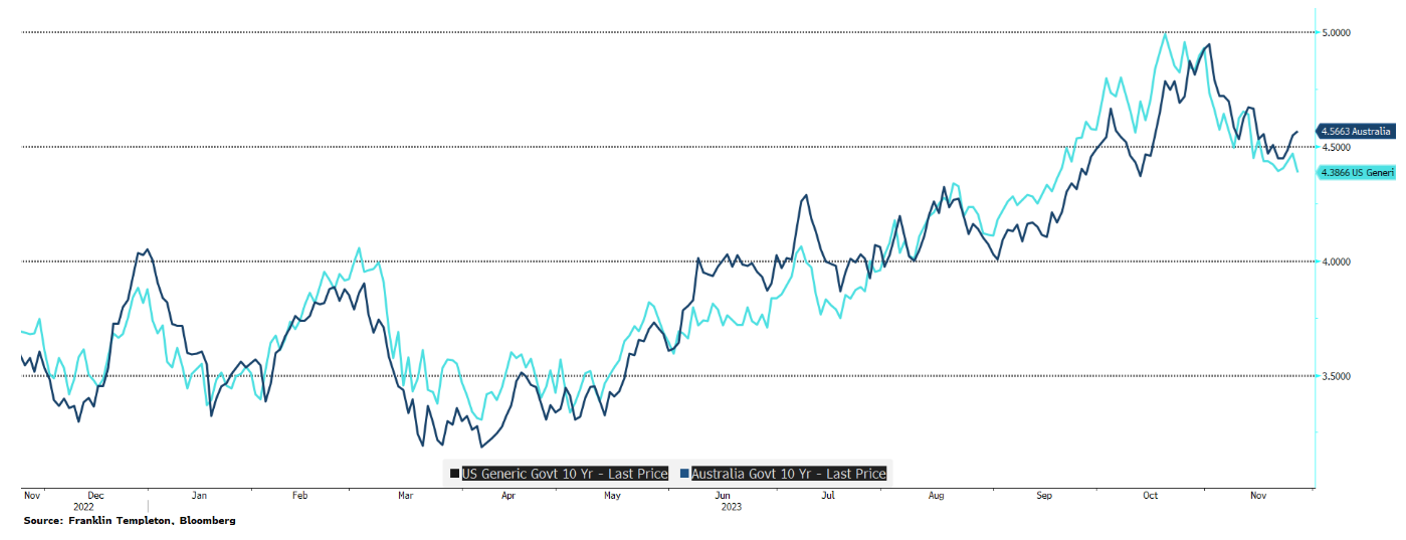

10-year government bond yields have been the wild thing, gyrating up and down regularly but so far already up ~100bps over 2023. Recently, after touching 5%, the US 10-year Treasury yield has retreated back to ~4.40%.

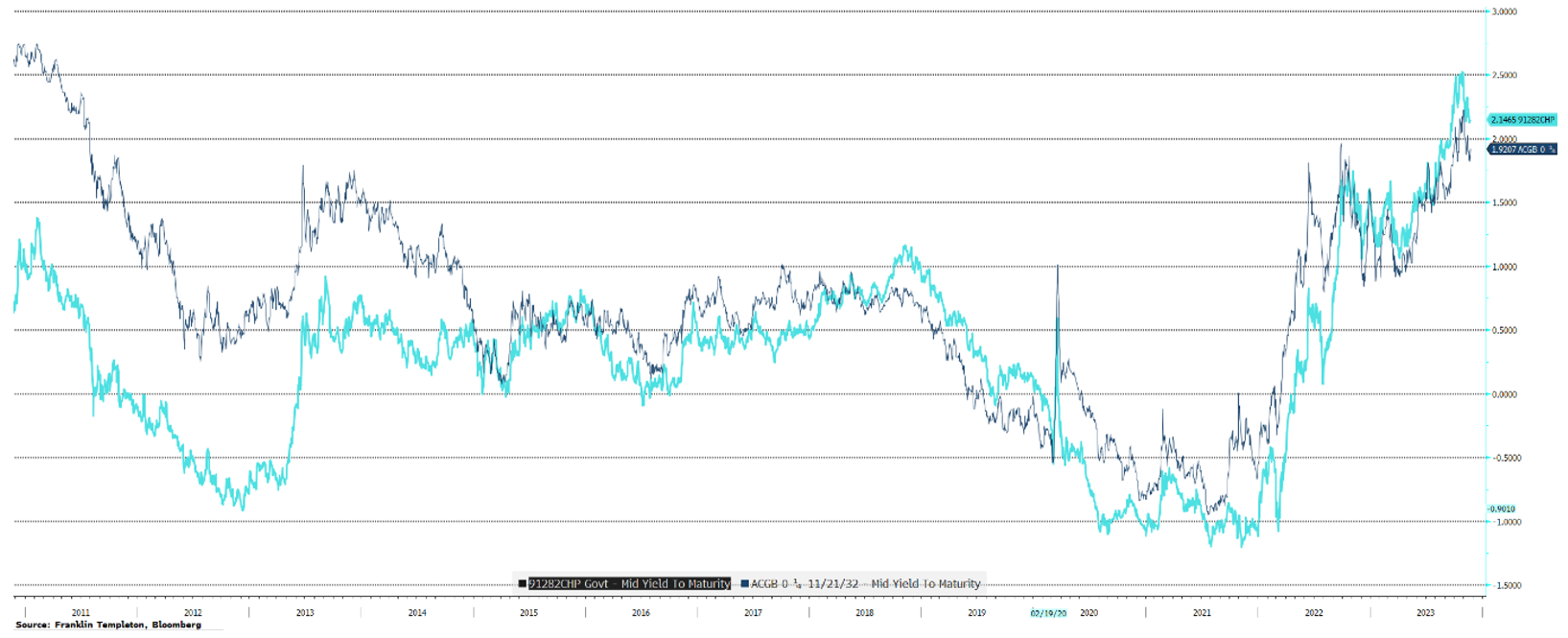

Australian and US 10-Year Government Bond Yields

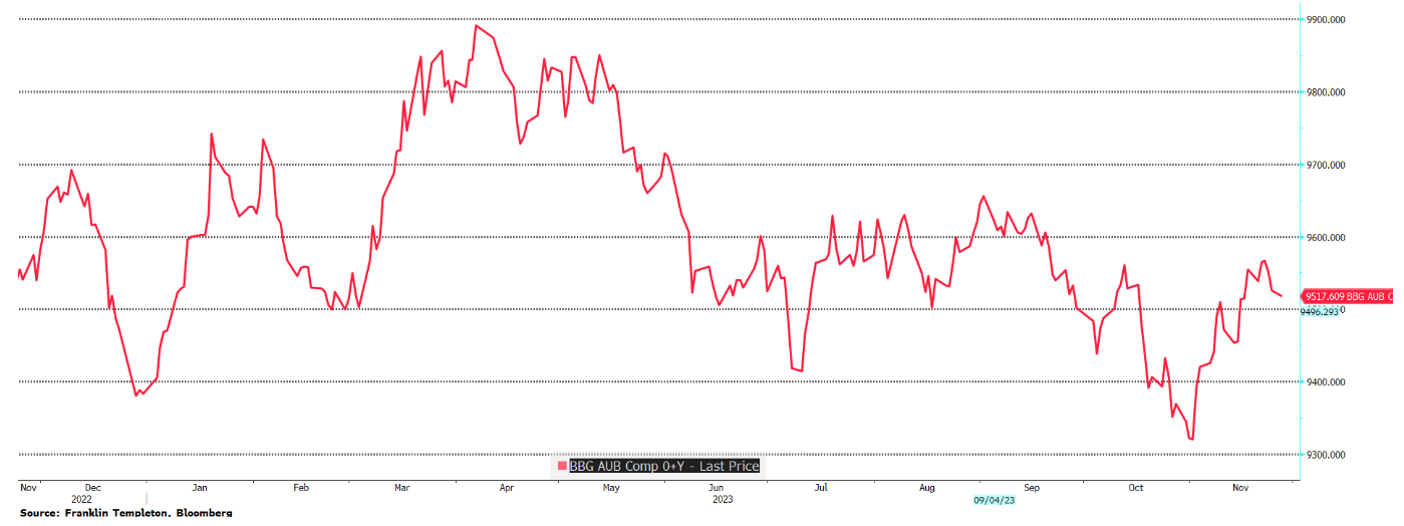

The impact of this is no more apparent than in broad bond benchmarks such as the Bloomberg Ausbond Composite Bond Index for which longer dated government bonds remain the driving force. After falling 1.85% in October, the index is up 2.18% so far in November whilst the one-year number sits at -0.30%, so more or less a round trip as we go up and down like a roller coaster.

Bloomberg Ausbond Composite 0+yr Bond Index Value

Newly appointed RBA Governor Michelle Bullock is likely to refrain from a Christmas Grinch moment at the last board meeting next week, but her hawkish tilt recently is a timely reminder that the RBA retains its finger on the rate hike trigger. As it stands, the outlook for 2024 is grim, as the full weight of 425bps of hikes continues to permeate the economy, the demand tailwinds from high population growth moderate and the savings spending splurge settles down. That may not be enough to sate the desire for the RBA to see more evidence of inflation cooling and prevent another rate rise in early 2024. While we believe sufficient tightening occurred one or two hikes ago, the delayed effect of these hikes compared to the slower response of inflation has led the RBA to favour a less patient approach.

If this is the outlook, why aren’t 10-year yields attractive? To be sure, the latest pop lower in yield looks like another false dawn. We are not constructive longer-dated government bonds at this stage, even with a gloomy prognostication ahead. There are far better opportunities in the market to access attractive returns without the gut-wrenching heart ache of the vol-ma-geddon of the longer end.

Here are three key reasons:

#1 - The path of policy:

10-year yields are at or below the policy rates for key economies. It’s very hard for 10-year bond yields to move much below the policy rate without starting to factor in an easing cycle. Much as it pains us to say it, central banks are likely to be the last to signal let alone deliver rate cuts. In the absence of a financial accident (which can’t be ruled out), rates are looking like they could stay above their pre-covid levels for some time.

At present, the US market has already priced for just under 100bps of easing by December 2024 and a further ~70bps in the following year – so ~170bps all in over the next two years. A more meaningful rally for US Treasuries requires the market to anticipate either: a) a larger rate cut cycle, b) the cycle to occur sooner, or c) some combination of the two.

These are of course possible, but we feel some catalysts need to start emerging to spark a bigger move and they continue to remain elusive. Right now, with US Treasury Bills offering 5.5% effectively at call, the rationale to own US 10-year Treasuries at 4.40% requires that next leg of policy easing to start to be anticipated. In short, the logical reason to own a 10 year at 4.4% (100bps less than US Treasury Bills) is because you think the yield is going to 3.5%.

In Australia, the market has virtually no change in interest rate policy projected to the end of December 2024. Commentators look at this and argue that this reflects the fact that the RBA is still 100bps or so below the Fed and come up with a ‘we didn’t get as high as the Fed therefore we won’t need to cut’ type argument. This isn’t particularly convincing to us.

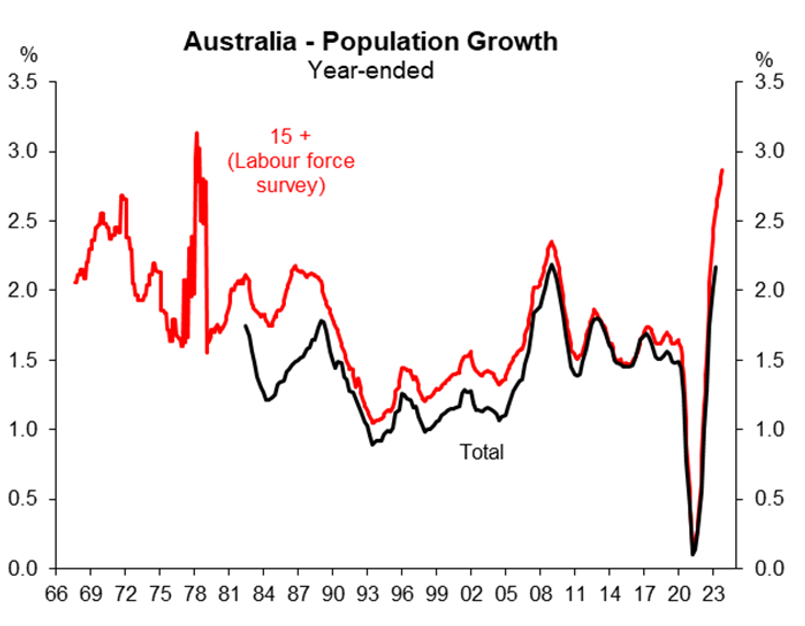

Our view has been that the peak level of rates in Australia would be lower than the US for reasons outlined many times, notably the swift transmission of rate moves to the household sector. More convincingly, however, is the argument for an RBA that could stay on hold for longer due to the demand shock from population growth that has caught everyone by surprise and injected an additional source of stimulus into the economy. If it hadn’t been for the population growth levels we witnessed the RBA would arguably have stopped raising rates well below the current setting. How much more is debatable.

Without this demographic increase, it's likely the RBA would have ceased rate hikes at a much lower level than where they currently stand. How much more is debatable.

Australian Labour Force and Broader Population Growth

Source: ABS; Franklin Templeton

The demand shock from population growth will abate but the market will struggle to price a meaningful easing cycle for some time. 10-year yields are likely to muddle around the current cash rate for some time. For 10-year yields to keep rallying and move below current policy rates gets harder unless the outlook for policy starts to factor in more easings.

#2 - Supply, supply, supply

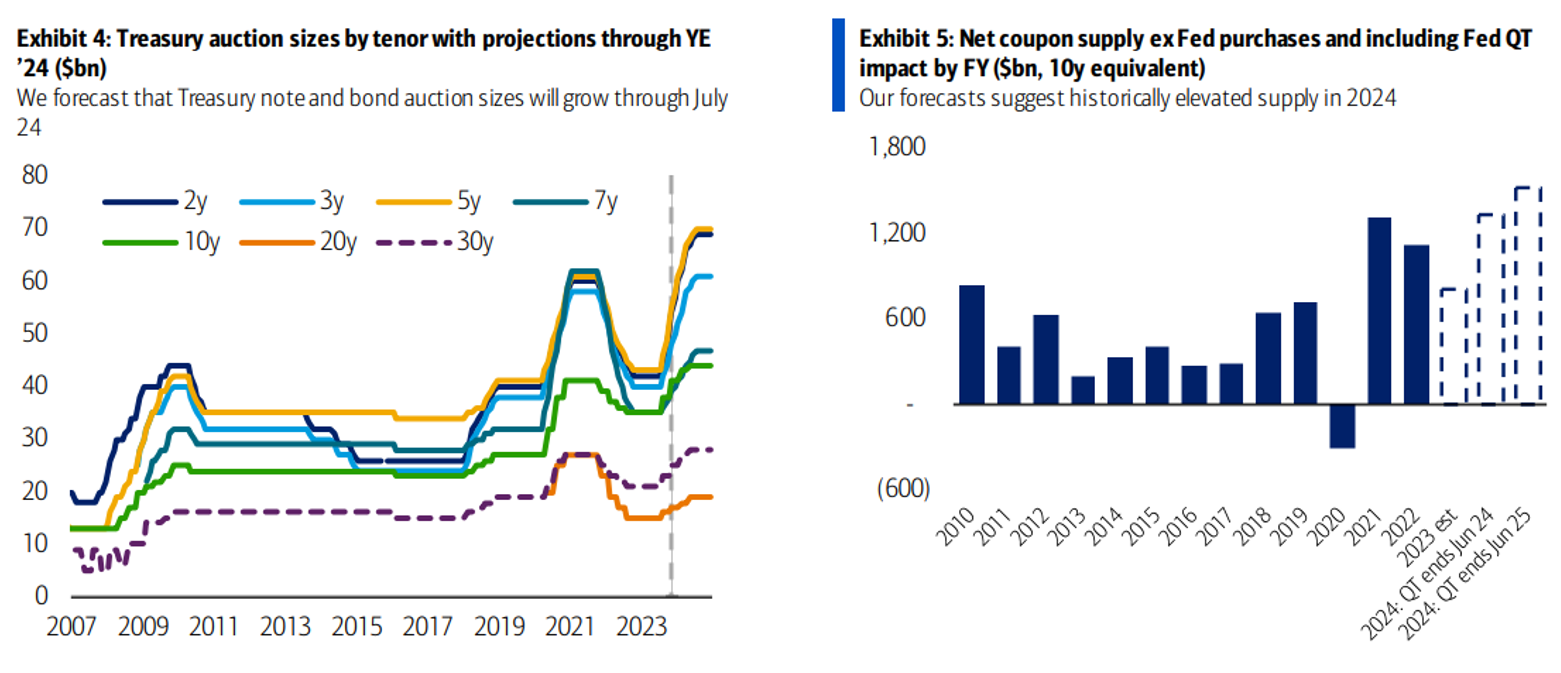

Even though forecasts for Australian government bond supply look lower as a more resilient domestic economy improves the budget thanks largely to income tax bracket creep, forecasts for US Treasury supply continue to look heavy as no-one in Washington seems to think living within ones means matters.

The US continues to run high fiscal deficits even in the good times. When the downturn comes, let alone recession, these will only increase. This means higher Treasury supply across all maturities and in total. Bank of America forecast average auction sizes for US treasuries (bottom left) to increase substantially through to mid-2024. Average sizes of 5-year Treasury auctions could go from ~$30-$40bn to a whopping $70bn in the next year. A lot of bonds from the world’s largest bond issuer are coming. US Treasury (coupon) supply in 2024 could double according to the same research.

Source: Franklin Templeton; Bank of America

Higher and higher US Treasury supply will weigh on US treasuries, which in turn will act as a brake on any rally in Australian government bonds. The direction of US 10-year yields continues to be the primary driver of Australian 10-year yields.

#3 - Inflation Premium

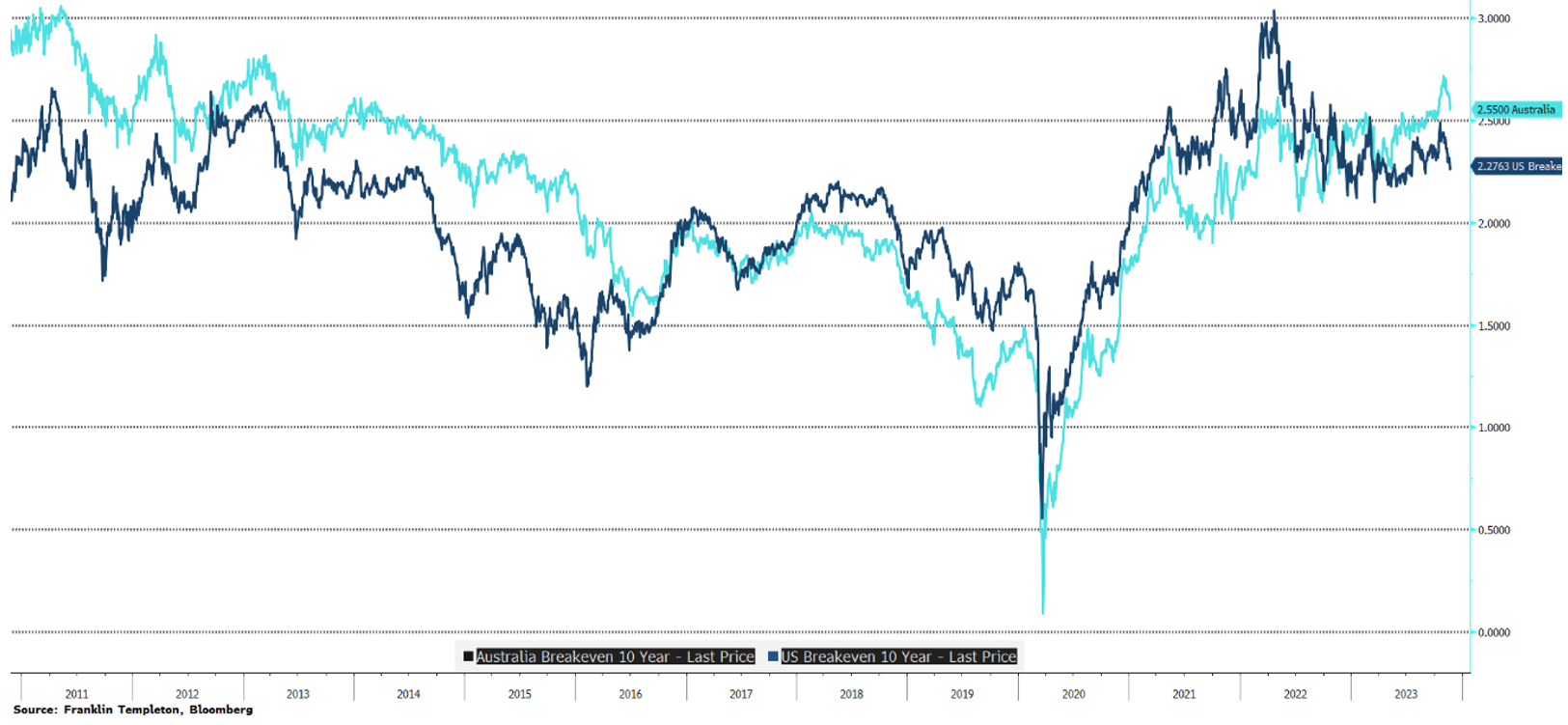

It’s been pointed out that real yields are high for 10-year bonds but the reason for this excess premium may relate to a safety cushion for unexpected inflation outbreaks in the years ahead. Real yields represent the current nominal yield minus expected inflation. With real yields at their highest levels in more than a decade and optically offering >2% inflation adjusted risk-free returns, isn’t this attractive? Yes, if you think we are going back to 2019 in short order. The key calculation in real yields is the expected inflation component known as break even inflation. Right now, the implied inflation forecasts (breakevens) that are used to derive the real yields above are in the 2.25-2.5% area. A little above the pre-Covid inflation breakeven levels but not completely out of whack with levels of the last 10 years.

Australian and US 10-Year Real Yields

Australian and US 10-Year Market Implied (breakeven) Inflation

With the current high level of real yields likely reflects market scepticism around risks for inflation and breakevens. In other words, real yields are high because a buffer needs to be built in for the risks that inflation fails to return to the benign ~2-2.5% level. This is optically keeping real yields at artificially high levels as the market is demanding additional compensation for risk that inflation fails to return to the 2-2.5% level over this 10-year horizon. Having lived through the unexpected inflation nightmare of the last 18 months, markets won’t relinquish this premium easily. This adds another reason to be cautious that 10-year nominal yields can rally much further in the short term unless the market decides forward looking inflation risks have receded materially.

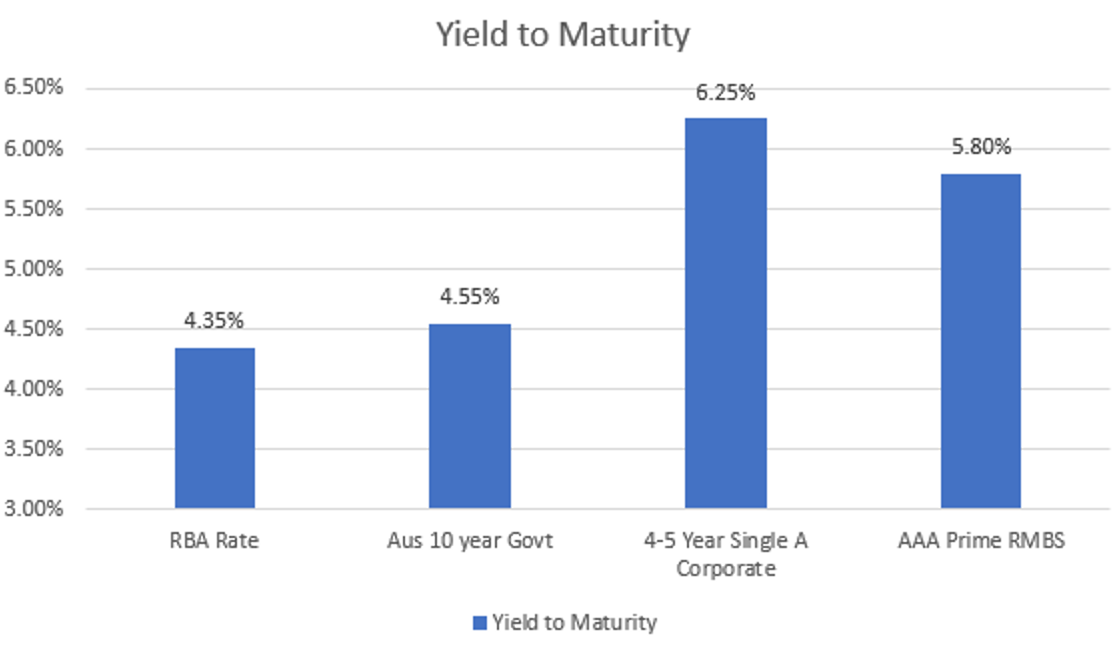

We think bonds are attractive, but one needs to choose the securities that are likely to deliver in this stop/start framework of heightened volatility. We continue to like sectors and exposures that offer high yields with some safety and or defensiveness such as investment grade bonds and prime residential mortgage-backed securities. Firstly, they have much higher yields than 10-year bonds and the current cash rate. This is particularly important as ‘yield’ has returned as a major driver of total return for fixed income, and we expect this to continue in 2024.

We do think that short ends of curves more linked to high cash rates can perform best when the cycle turns. We remain sceptical that longer dated government bonds will rally much further in the short term and indeed the latest fillip looks to be petering out as we write.

Source: Franklin Templeton, Bloomberg Data

.png)

1 fund mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)