Why China's economic growth is slowing and what it means for Australian investors

Scepticism about China’s economic success has been an issue for years. But it’s intensified lately on the back of slowing growth, property problems, high debt and falling long-term growth potential with talk that China is “teetering on the brink” and President Biden describing it as a “ticking time bomb”. After strong growth and a big run-up in debt there is fear that it’s going down the same path as Japan which after a surge in asset prices and debt on the back of what was dubbed a miracle economy in the 1980s slipped into a long period of poor growth and deflation. As the world’s second-largest economy, what happens in China has significant ramifications globally and in Australia. This note looks at the main issues and what it means for Australia.

Slowing growth

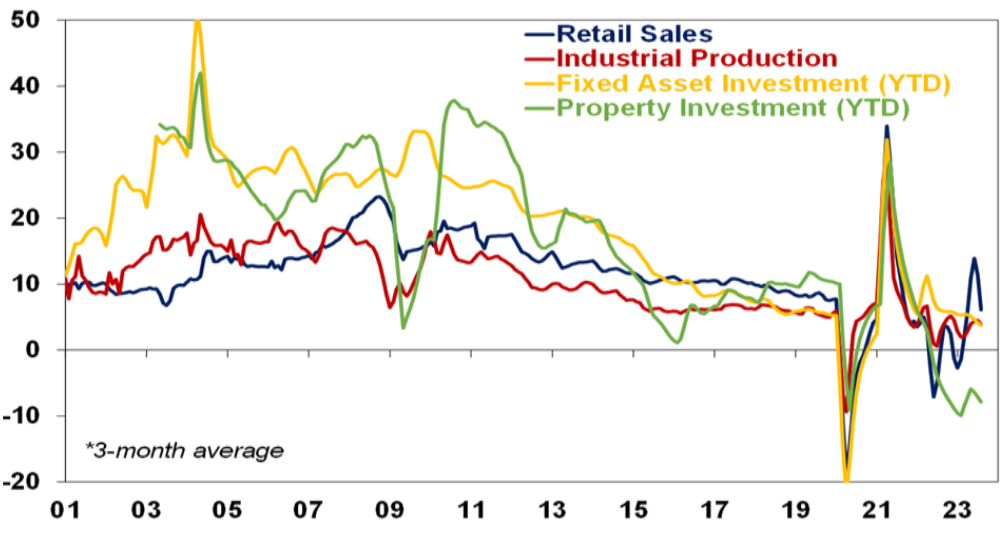

After China’s Covid restrictions were finally eased late last year there was hope its economy would rebound. It did in the March quarter but since then its disappointed with GDP growth slowing to 0.8%qoq (from 2.2% in the March quarter) and July data showing a further slowing in growth in industrial production, retail sales (running at just 2.5%yoy) and investment.

China activity indicators, smoothed annual growth (%)

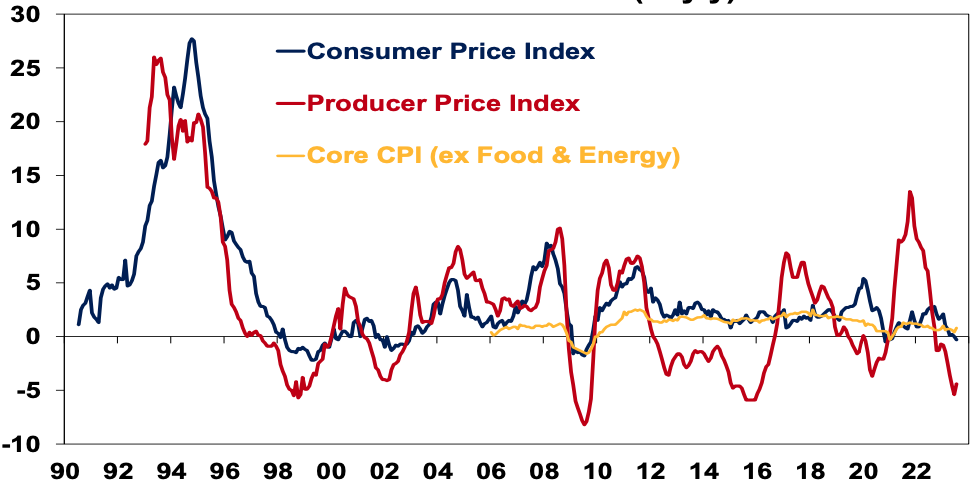

Exports and imports are down 14.5% yoy and 12.4% yoy respectively, bank lending and credit growth have slowed despite some monetary easing. Reflecting weaker conditions, business conditions PMIs have also fallen sharply. And youth unemployment has risen from around 12% to 21% over the last five years. Reflecting faltering growth, modest inflation has given way to deflation, although core CPI inflation is slightly positive.

China inflation measures (% y/y)

The slowdown reflects a combination of factors but high on the list are:

Many households seeking to rebuild savings that were depleted through the lockdowns – Chinese households did not have their incomes protected as in most Western countries in the lockdowns so did not emerge with lots of excess savings compared to pre-Covid levels.

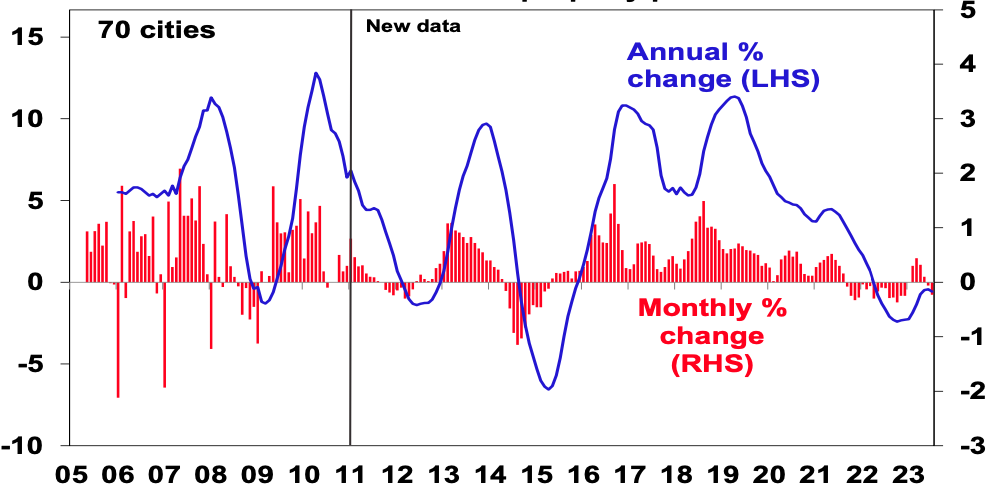

A property collapse – after reaching record highs in 2021 new home sales are down sharply, property transactions are down 33%yoy and home prices have fallen reflecting tightening policies and oversupply. This has led to big problems at:

- developers (eg, Evergrande and Country Garden) that relied on high debt & a steady flow of new buyers;

- companies that issue investment products that helped finance developers;

- local governments that rely on land sales for revenue; and

- households who have seen property-related investments sour.

Chinese residential property prices

Structural problems

However, the slowdown is also being impacted by structural problems:

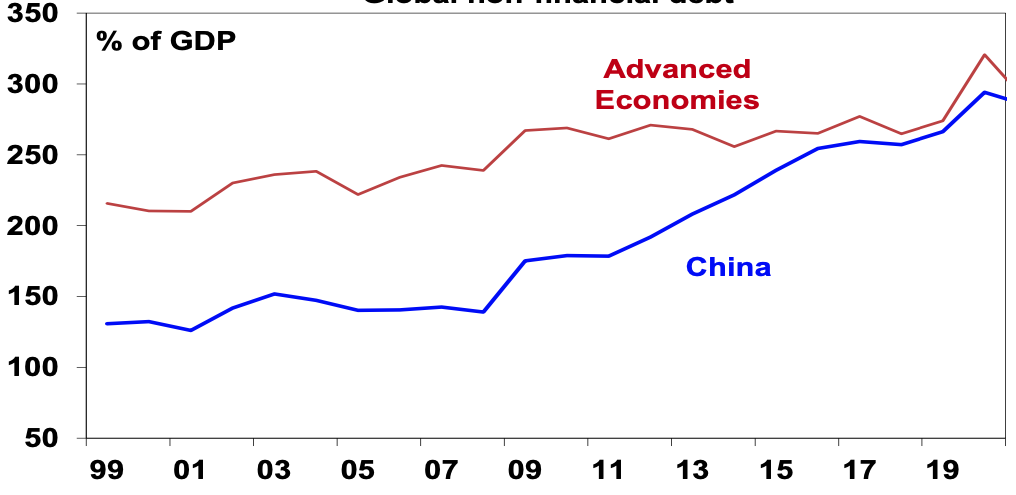

The first thing to note is that China has a very high saving rate of around 45% of GDP, which is roughly double that of countries like Australia. This makes China’s debt problems very different to other countries as China has borrowed from itself (so there are no foreigners to cause a foreign exchange crisis). But it means the savings have to be recycled (usually via debt) into demand or else weak demand, high unemployment and chronic deflation can result. It did this initially through corporate debt into investment and then into property which has resulted in a rapid rise in China’s debt levels since 2008. But this is getting problematic.

Global non-financial debt

Second, the easy opportunities for capital investment have been taken. China’s ratio of fresh capital to GDP and fresh debt to GDP have increased substantially indicating that ever more investment and debt is necessary to achieve the same increase in GDP as in the past.

Third, this hasn’t been helped by geopolitical tensions which have slowed exports. It’s also added to a plunge in foreign direct investment (which is down 87% yoy) and restricted access to US technology.

Fourth, while some cried wolf too early on China’s property market (recall the SBS Ghost Cities story from 2011!), using property to recycle high savings is souring. This was viable when urbanisation was rapid but analysis based on utility usage and light emissions at night suggest some areas may have 25% of apartments vacant.

Fifth, China’s demographics are poor as its workforce is now shrinking and it has a rapidly aging population. This also weighs on property demand. But it also removes a key source of economic growth.

Finally, despite a falling workforce China could still grow quickly because its GDP per capita and output per worker are around 20% of US levels – so it still has a lot of catching up to do. However, the easy gains of industrialisation by putting people in front of machines have been had and China runs the high risk of falling into the “middle income trap” (where countries fail to transition to being high income countries) as a result of increasing state intervention in the economy – with the resurgence of less efficient state owned enterprises (which now account for 60% of investment, up from 30% 10 years ago) and regulatory crackdowns on tech companies and other sectors acting as a disincentive to future entrepreneurs, state intervention on national security grounds and tighter access to foreign technology. As a result of China’s falling workforce and slowing productivity growth, estimates of its potential real GDP growth have fallen from around 10% in 2006-10 to around 5% now and around 3% next decade.

The policy response and “Japanification”

The fear is that China continues to slow causing a spiral of bigger property sector problems with sharp falls in asset prices, more developers “failing”, increased consumer caution, weaker growth, and further falls in asset prices. Or that a major near crisis is averted but it slides into a decades-long period of stagnation and deflation like Japan did after its 1980s boom years.

With opportunities to recycle China’s high saving rate into investment and property starting to diminish it should be saving less and spending more. To achieve this requires aggressive fiscal stimulus to rebalance the economy towards consumer spending. In particular, this would involve improving social welfare (in terms of pensions, health and education) in order to lower precautionary household saving and support spending.

Despite indications from Politburo meetings that stimulus would be forthcoming so far it’s been mild with only a few cuts to interest rates and relaxation of bank reserve requirements and measures to “promote” consumers to spend more and buy more homes without large-scale measures to help them do so. This has led to concern the Government is more focused on trying to avoid reflating credit and housing bubbles (much as Japan was in the early 1990s) and/or is not aware of the problem.

Our assessment though is that the Government is well aware of the need to support growth given the risk of social unrest and will ultimately do so – probably after the summer travel boom comes to an end soon. Furthermore, the Chinese Government is unlikely to allow a GFC-style collapse in property developers and is likely to continue to manage the problem.

So, a collapse in the Chinese economy is unlikely but the risk that policy stimulus is too little or too late can’t be ignored, nor can the broader comparison with Japan at the end of the 1980s. A key difference with Japan 30 years ago is that China’s per capita GDP is still low so it still has lots of catch-up potential. But its rapid private debt build-up is similar to Japan’s, its demographic outlook is a bit worse and the threats to its productivity (with state intervention) and trade (with geopolitical tensions) are greater.

The Chinese share market

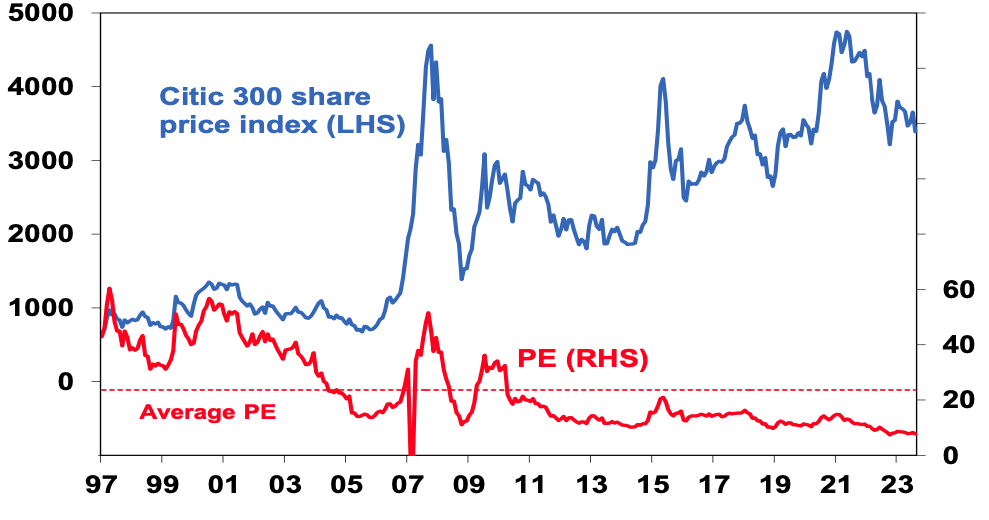

Chinese shares are down 36% from their record 2021 high and are cheap when compared to earnings (trading on a PE of just 7.7 times), book value and sales. This suggests significant potential for a bounce if significant stimulus is announced. However, the risks are on the downside.

Chinese shares are cheap

Implications for Australia

Uncertainty around China’s outlook is a key risk for global growth at present and could be a contributor to a further correction in share markets.

The collapse in the share of Australian goods exports going to China in 2021 and 2022 from around 42% to less than 30% (partly due to trade restrictions) without a major hit to our economy highlights that maybe Australia is not as dependent on China as many think. Nevertheless, a sharp downturn in China would be a double whammy for the Australian economy coming at the same time the lagged impact of big interest rate hikes on household spending comes through.

But while it’s a risk it’s not our base case as ultimately we expect a ramp-up in Chinese stimulus measures enabling Chinese growth to settle around 5% this year and 4.5% next year (not great compared to the past experience for China but not a disaster). However, the risks around the Chinese outlook and its longer-term growth mean Australia cannot rely on the China/commodity boom indefinitely driving national income and hence masking our poor productivity performance. This is another reason why Australia needs structural reform to boost our longer-term growth potential.

1 topic