Why Howard Marks says uncertainty can be an investor's saving grace

If everything in life was a dead certainty, we would have never had a YouTube video with this title:

And yes, do the math. This was former Obama Administration senior adviser David Plouffe telling Bloomberg Television why the then-Republican Presidential Candidate could not win the 2016 election. The hosts in this interview even said in the video that Plouffe thought Hillary Clinton had a "100%" chance of winning.

Well, we know what happened next.

This and other instances prove that there is a "folly of certainty".

Recently, legendary investor and Oaktree Capital Management Chairman Howard Marks penned a note on this exact topic. In his memo, Marks asked "how anyone can be without doubt" about the current state of the world, adding "There’s no way a macro forecaster can produce a forecast that correctly incorporates all the many variables that we know will affect the future as well as the random influences about which little or nothing can be known."

Instead, investors should just remain humble and acknowledge what they don't know. This wire will summarise this latest memo - a gem that is, in my humble opinion, a must-read.

Avoid certainty in your (or anyone else's) predictions

In a part of Marks' introduction to this memo, he provides a list of words that investors should not use. While simple, the list cuts straight to the point of this piece:

"...investors and others who are subject to the vagaries of the macro-future should avoid using terms such as “will,” “won’t,” “has to,” “can’t,” “always,” and “never.”

In reference again to the 2016 Presidential Election, Marks noted that of all the predictions he had read, most of them said Hillary Clinton would win and that if Donald Trump won "by some quirk of fate", the stock market would collapse.

Well, neither of those things happened.

So what was the lesson for Marks?

"The response of most forecasters was to tweak their models and promise to do better next time. Mine was to say, “If that’s not enough to convince you that (a) we don’t know what’s going to happen and (b) we don’t know how the markets will react to what actually does happen, I don’t know what is," he writes.

He goes on to add:

"Sometimes things go as people expected, and they conclude that they knew what was going to happen. And sometimes events diverge from people’s expectations, and they say they would have been right if only some unexpected event hadn’t transpired. But, in either case, the chance for the unexpected – and thus for forecasting error – was present. In the latter instance, the unexpected materialised, and in the former, it didn’t. But that doesn’t say anything about the likelihood of the unexpected taking place," he says.

You could also say this for economists

As much as it pains me, the presenter of Livewire's economics show, to write this, the sentiment of this note is particularly salient for economists.

Exhibit A was that period in 2021 when the US Federal Reserve was convinced that inflation would be "transitory". Inflation would be temporary and self-corrected in a short time. Well, as Marks reminds us, "because the Fed’s view wasn’t borne out in 2021 and waiting longer was untenable, the Fed was forced to embark on one of the fastest programs of interest rate increases in history, with profound implications."

Exhibit B came right afterwards. During 2022, most economists said there would be a brutal recession coming as a direct result of the dramatic policy tightening made by most central banks. After all, history and logic were on their side. It appeared to be - all together now - a certainty. But a recession has not materialised in the US so far.

Note, that this is not to say that it won't. It just has not materialised so far.

Exhibit C is the debate we are all having right now - rate cuts. As Marks so eloquently puts it:

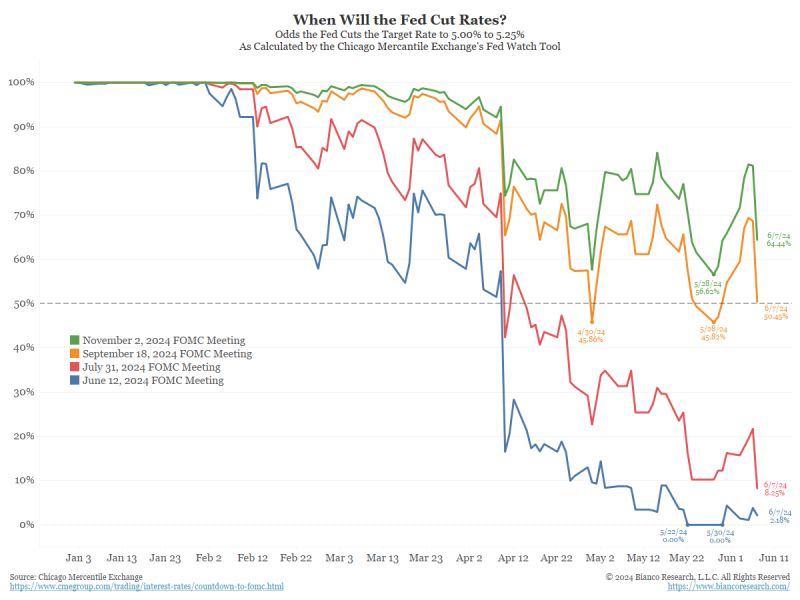

"In December 2023, when the “dot plot” of Fed officials’ views called for three interest rate cuts in 2024, the optimists driving the market doubled down, pricing in an expectation of six. Inflation’s stubbornness has precluded any rate cuts thus far, with 2024 more than half over. Now the consensus has coalesced around the idea of a first cut in September. And the stock market keeps hitting new highs," he writes.

It proves that the economics consensus doesn't know any more than the Fed does. And based on this chart, neither does the market! All those jagged lines demonstrate how market pricing has changed over time for upcoming Federal Reserve meetings. You can have a certain view all you like on interest rates - but one data point can easily shatter that prediction.

Indeed, even if you correctly predicted that the Fed wouldn’t cut interest rates for the next 18+ months, chances are that prediction kept you out of the stock market - and you would have missed out on a gain of roughly 50% in the S&P 500.

Conclusion? "The only thing worthy of certainty is the conclusion that economists shouldn’t be expressing any of it."

So why do we keep making predictions?

"The performance of economies and companies might tend toward predictability given that the forces governing them are somewhat . . . shall I say . . . mechanical. In these areas, one might say “If A, then B” with some degree of confidence. Predictions here might, therefore, have some chance of being correct, albeit that’s mostly the case when trends continue unabated and extrapolation works," Marks writes.

In addition, market forecasts cannot possibly take into account changes in sentiment and the feeling among investors.

"Investor sentiment swings a great deal, swamping the short-run influence of fundamentals. It’s for this reason that relatively few market forecasts prove correct, and fewer still are “right for the right reason.”

What can we do to avoid looking foolish?

To quote Marks' previous notes entitled Uncertainty and Uncertainty II, investors need to engage in some "intellectual humility".

"To put it simply, intellectual humility means saying “I’m not sure,” “The other person could be right,” or even “I might be wrong.” I think it’s an essential trait for investors," Marks wrote back then. He went on to say:

"No statement that starts with “I don’t know but...” or “I could be wrong but....” ever got anyone into big trouble."

Sure, it will mean you may not get the maximum return out of a risky investment. But at least, if you're wrong, you won't flame out.

"Eschewing certainty can keep you out of trouble. I strongly recommend doing so," he goes on to say.

In conclusion, doubt is an unpleasant condition to be in. But it's a whole lot better to be at least a little unsure of a result or an event's impact rather than being blindingly certain and then left holding the bag. Oh - and stop making forecasts. Chances are you'll be wrong anyway.

5 topics