Why inflation globally should come down

“There’s a tendency for markets to focus on the present and extrapolate it forever”, said Olivier Blanchard, a well-respected economist formally of the IMF. We could probably apply this idea to not just markets, but human nature in general. It seems that whatever times that we are in, we tend to think that they will continue.

Presently, we are in an environment where inflation in many advanced economies around the world have hit multi-decade highs. Moreover, this bout of inflation has caught policymakers by surprise, who have vastly underestimated the persistence high inflation.

Now, in a major about face, after insisting that high inflation was transitory for many months, policymakers are talking tough on inflation. Heads of the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) have even hinted that the period of low inflation that we have experienced in recent decades might be a thing of the past.

Is higher inflation here to stay?

Some analysts have pointed to the Ukraine war, escalating geopolitical tensions and the ongoing supply constraints as an argument for a longer-lasting increase in inflation.

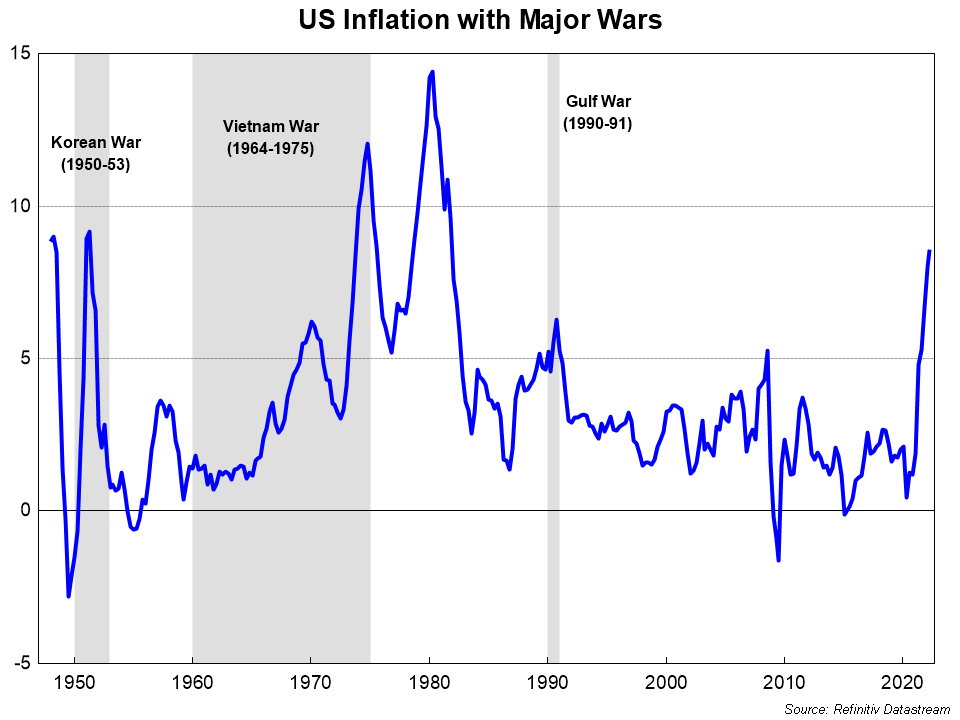

Indeed, history has shown that inflation has tended to rise in times of world conflict, as can be seen in the chart below showing US inflation and major wars of the past 70 years.

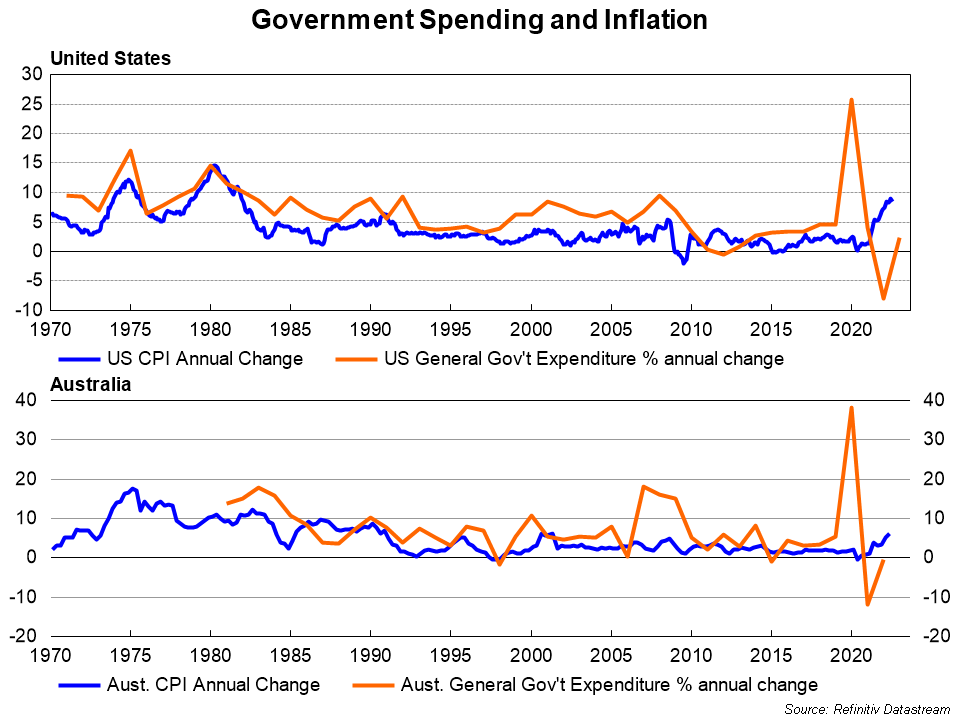

Bigger military spending, the destruction of capital, the diversion of resources towards producing armaments and disruption of goods and services can explain the high inflationary periods around war. It is important to note the big increase in fiscal spending that has coincided with high inflation during war or post-war periods. Taking a look at government spending and inflation, the two have moved closely together with the former leading the latter, particularly in the US.

In 2020, fiscal spending increased significantly globally. However, this was not necessarily because of increasing geo-political tensions, but because governments wanted to support their economies in response to the pandemic.

Nonetheless, because conflict can disrupt supplies of essential goods, war can also impact inflation through a supply shock as well.

On top of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine has no doubt constrained the global supply of key agricultural and energy commodities. And global geopolitical tensions were already on the rise before we knew of the word covid.

Sanctions, and geopolitical tensions disrupt the free movement of goods and the less friendly business climate indicate that supply chains are likely to shift towards prioritizing security over efficiency.

These shifts suggest that could be a longer-lasting downward shift in the productive capacity of the global economy, ie. reduced supply. But the overwhelming driver of more persistent inflation in the past has generally been through stronger demand and many times this has occurred through a surge in government spending.

But What About the Central Bank?

A discussion on inflation is not complete without assessing the role of the central bank. After all, over the past 30 years, it has been central banks which have been tasked with keeping inflation at a certain target. No other authority has a bigger responsibility in managing inflation.

So, could the US Fed have prevented the surge in inflation? We will never know, but we do know that the Fed was late in recognizing the scale of inflation risks.

The Fed thought of the impact of covid-19 as a temporary shock, but the effects of the pandemic seriously shifted the productive capacity of the economy for much longer than it thought. It also underestimated the inflationary impact of the government stimulus in response to covid.

When inflation just began to emerge, there seemed to be a preoccupation with supporting growth and underestimating of inflationary risks. In a speech in August 2021, Fed Chair Powell spoke of the unemployment rate at 5.4% as being too high, although PCE (headline) inflation had hit 4.2%.

This sentiment is eerily similar to the early stages of the high inflation period of the late 1960s and 1970s, which has been dubbed the Great Inflation in the US. Studies of that period suggest that an inadequate monetary policy response when inflation started to emerge was a factor behind the inflation spiral in the years that followed. It was also a time in which government spending was ratcheting higher, due to the escalating cost of the Vietnam War, but also because the government at the time was focused on boosting the economy.

This worry about stabilizing growth meant that policy settings were not restrictive enough for inflation to come down in a sustained way.

Inflation didn’t recede until the early 80s when Fed Chair Volcker shifted inflation to the highest priority, regardless of the risk of recession. Indeed, two recessions were the result in the early 80s.

It’s no wonder that Powell has taken a page out of Volcker’s book in talking tough on inflation and seems prepared to allow a recession to bring it down.

But this resolve to place inflation at the top of the Fed’s agenda is exactly why inflation should come down.

If inflation does not recede sufficiently, the Fed will continue to hike rates, which would in turn lead to weaker demand and bring down inflation.

Powell’s tough stance is necessary for inflation to come down and to ensure that inflation expectations remain in check.

There are already also indications that global demand is slowing. Also note that government spending has fallen dramatically. The massive pandemic stimulus is not going to be repeated so this suggests a major fiscal consolidation is underway for many advanced economies. This weaker demand further highlights the likelihood that weaker inflation should follow.

There is one caveat though.

For inflation to come down, it will need persistent resolve by central bankers and governments to tighten policy, and this will be amid the temptation will be to support the economy or provide households with assistance to address rising cost of living pressures.

You can’t fight inflation by throwing more money at it. Provided authorities have learnt the lessons from the past, inflation is likely to come down one way or another.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with content like this by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time we post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

4 topics