Why investors are wrong about the Fed

Over the past 25 years, global investors have become conditioned to the notion that central banks will bail out global asset markets amid the first sign of stress. Many of these occurrences have been when the economy has been firmly in expansion territory such as 1998 when the Russian default crisis and the collapse of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) saw the Fed cut rates during one of the biggest economic and speculative equity booms in recorded history. Twenty years (and a few months) later, the Fed was completing one of its slowest tightening cycles ever and decided to go on hold in early 2019 because the US equity market had declined -20% in Q4’18, and then they cut rates in September 2019 when US unemployment was at a fresh 50-yr low of 3.5%, which sparked a huge gain in the S&P 500, despite zero earnings growth.

Although there are numerous other examples of the Fed, in particular, bailing out markets in the past quarter century, all of these policy pivots were possible as their preferred inflation gauge, the core Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (PCE), was close to the +2% target. In 2022, investors have once again formed an expectation that the Fed could pivot on policy and be easing rates as lower commodity prices means financial conditions may not need to tighten as much as previously thought to get core inflation back to 2%. This is a challenging notion as reducing inflation from 6% to 4% will be much easier, than from 4% to 2% without a recession.

Bear market rallies are common

Expectations of rate cuts in 2023 sparked a very strong rally on Wall Street in the two months to mid-August and this has echoed around global financial markets resulting in lower bond yields and narrower credit spreads, all of which is working against the Fed’s plan to tighten financial conditions. The +17% rally in the S&P 500 since the 16th June market low can be temporarily painful for investors who are underweight risk, but rallies of this size and nature are very common, even in equity bear markets.

Indeed, in the US equity market sell off during the Great Depression, the S&P 500 sold off -89% in 33 months, but within that time frame the index recorded 10 periods in which it rose more than 10% and had five periods of gains in excess of 25%. Similarly, in the six bear markets since 1979, the S&P 500 has recorded an average bear market rally of +16% (Chart 1) and the majority of these have occurred in recessions (only 1987 and 2022 happened during an expansion) as investors responded to a combination of improved valuations and increased stimulus.

Chart 1: The average US bear market rally has been +16% since 1979

Source: Bloomberg as at 18/08/22.

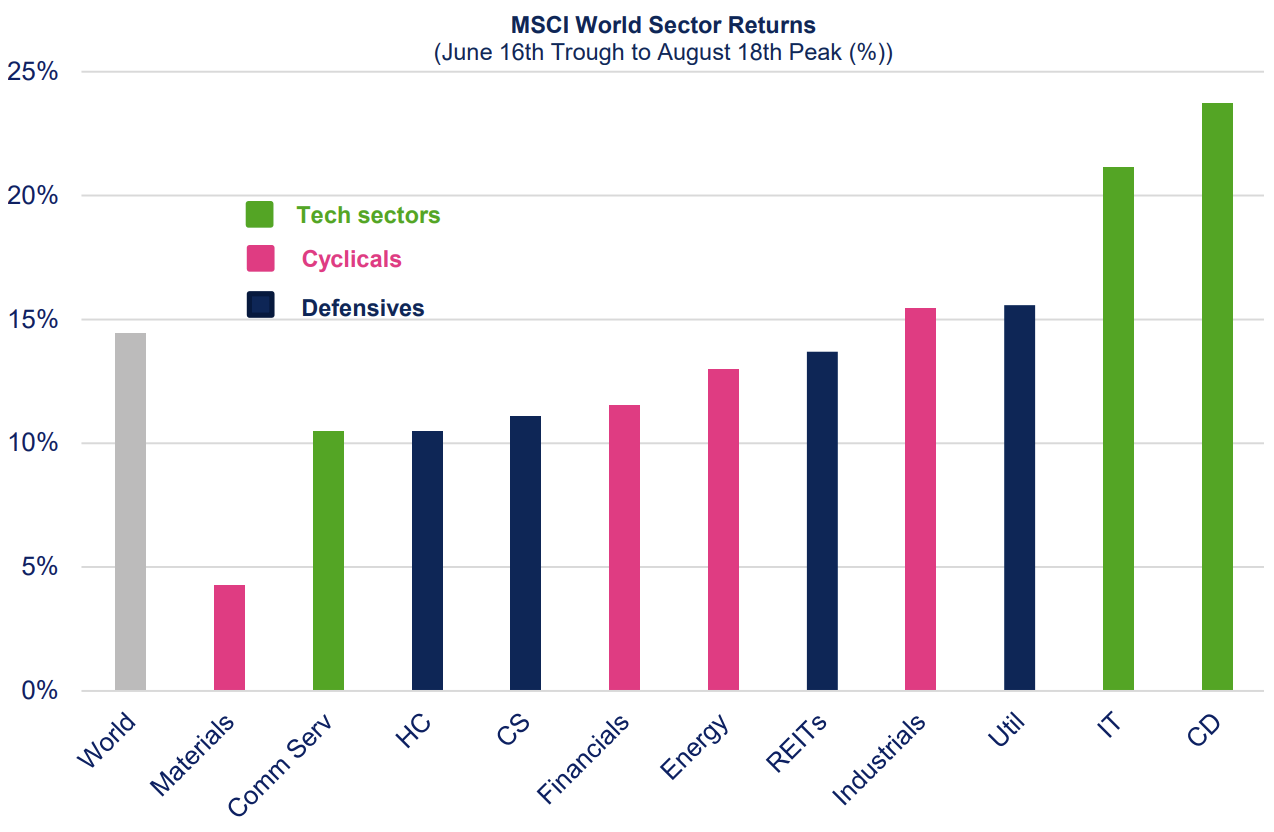

Rallies of this size and speed, despite the high-risk economic backdrop, can spark a fresh re-examination of the market outlook by investors. In a technical sense, the strong market bounce since June has been driven by the three P’s – namely, expectations of more dovish central bank “P”olicy amid lower oil prices, light “P”ositioning by investors in mid-June as they feared a 2022 recession given high inflation and tightening financial conditions, and the June quarter US and European “P”rofit reporting season which was less bad than feared (even though US EPS growth was -3% ex-energy). Expectations of rate cuts in 2023 has sparked a decline in real US 10-yr bond yields and a sharp rally in equity sectors which underperformed in the first half of 2022 (Chart 2).

Chart 2: The post June 16th rally has been driven by sectors which underperformed in H1’22

Source: Bloomberg as at 18/08/22.

The tech sectors (green bars) have led the price recovery as they are the most sensitive to falling real interest rates, but defensive sectors have also performed strongly in response to increased safe haven flows, whereas cyclical sectors such as materials and energy have lagged as the growth picture has deteriorated. The decline in real yields and the rally in tech sectors is reminiscent of what occurred when the Fed last bailed out markets in 2019 a year during which the S&P 500 rallied +32% and EPS growth was zero.

The key question for investors

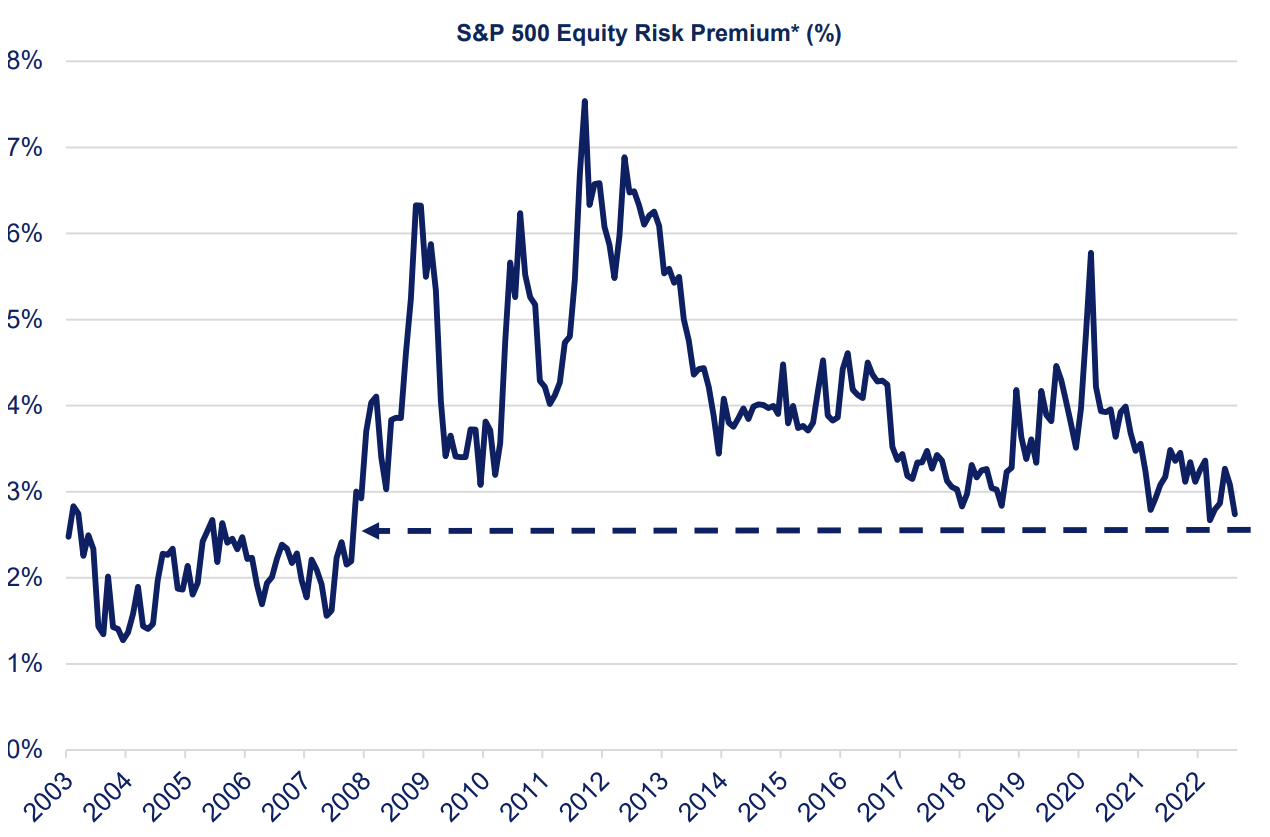

Investors know they need to bear risk to achieve their investment goals, but they always need to ensure that they are being appropriately compensated for the risks they are taking in their asset allocation. Although the implication of its use is not always straight forward, one gauge to assess if risk and returns are appropriately aligned is the equity risk premium. At present, the ERP is at 2.75% which is the lowest since November 2007 (Chart 3), just before one of the longest and largest selloffs in US equities since the 1930s.

Chart 3: The US equity risk premium is at a 15-year low of just +2.75%

Source: UBS Australia and Bloomberg as at 13/08/22. Calculated using the Gordon Growth Model, US 10-yr Bond Yield and 12MF PE Ratio.

The conditions for a sustained bull market remain absent

One challenge with such a lower equity risk premium is that many investors could think we are not in a low risk environment, and this makes the market highly vulnerable if the Fed does not pause on tightening soon, or the earnings outlook does not improve. Despite some similarities, the two key differences to 2019 are that the Fed is in no position to pause its tightening cycle with inflation so high, and also that all economic lead indicators are pointing to serious economic risks ahead which is likely to weigh on earnings growth – these include the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing gauge, an inverted US 2s-10s yield curve slope, low consumer and business confidence, declining housing activity and rising jobless claims.

Accordingly, the current environment is one where the economic slowdown in the global and US economies are unlikely to quell inflation, central banks continue to move rates into restrictive territory and are likely to cut rates in the next 12 months only if there is a recession, and finally that valuations have improved but are certainly not cheap. Consequently, the conditions normally present to drive a sustained bull market all remain elusive in the current environment.

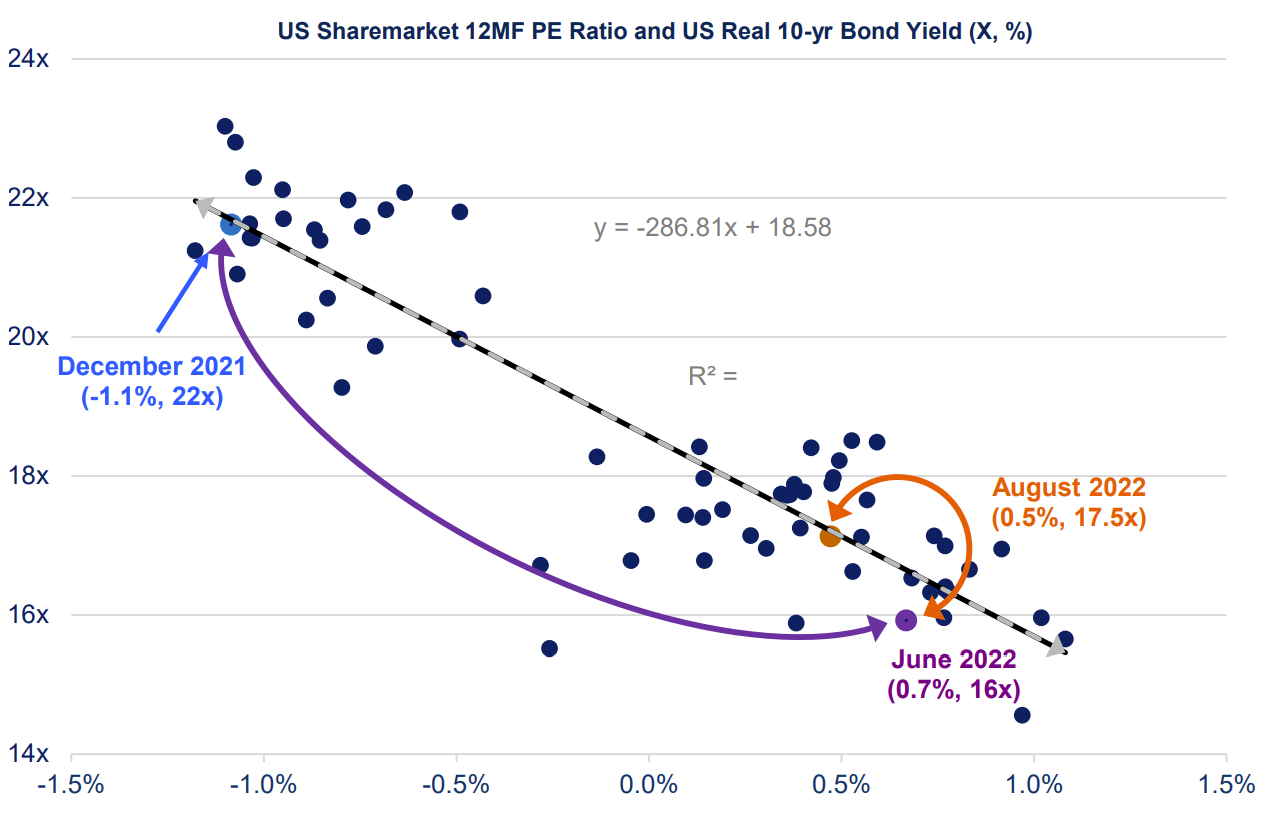

The first stage of the price declines was falling valuations

There is little doubt that investors were highly optimistic about return prospects coming into 2022 with widespread forecasts of above-trend global GDP growth, close-to-target inflation and low prospects of aggressive policy tightening. However, aggressive policy tightening has seen all risk markets decline in what could evolve into a two-stage sell down. The first stage was driven by higher real bond yields which sparked a -20%+ valuation decline (Chart 4), and this occurred at a time of continued earnings growth in all developed markets of between +5% and +15%.

Chart 4: The H1’22 price decline in regional equity markets reflected falling valuations

Source: UBS Australia Limited as at 9/07/22.

A chart of the market-based US 10-yr inflation adjusted bond yield and the 12-month forward month forward PE ratio of the S&P 500 over the past 5 years, shows that the relationship between the variables has been very tight with the R-squared at 80%. When US real 10-yr yields troughed at a record low of -1.1% in December 2021, the corresponding valuation of 21.6x was one of the highest since the tech boom of the late 1990s. However, in July 2022, real yields have risen to +0.7% and the valuation is now at the other end of the trend line at 15.9x. By end-August real bond yield had declined to +0.4% and PE ratios had risen to 18x –meaning the 12MF PE ratio has simply been moving up and down the grey trend line (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Valuations declined due to rising US real 10-yr bond yields, but this partially reversed in July and August

Source: UBS Australia as at 18/08/22.

The strength of the relationship between real bond yields and regional sharemarket valuations is mostly determined by the index composition of respective stock indices. For example, the MSCI World Growth index which has a very high proportion of tech and biotech firms in its universe has an R-squared stat (which shows the strength of the relationship between two variables on scale of 0 – 100%, with 0 being very weak and 100% being extremely strong) of 90% with the real US 10-yr bond yield, whereas the relationship is much weaker with a cyclical sharemarket like Japan at 37%, whereas for a highly defensive market like the UK, its just 3%. So, the story of the decline of regional sharemarkets in H1 2022 was not all equities being hyper-sensitive to higher real 10-yr bond yields, but growth stocks being so and the markets and the sectors with higher sensitivity to the tapering and eventual ending of central bank asset purchases underperformed.

The earnings outlook looks challenged on many fronts

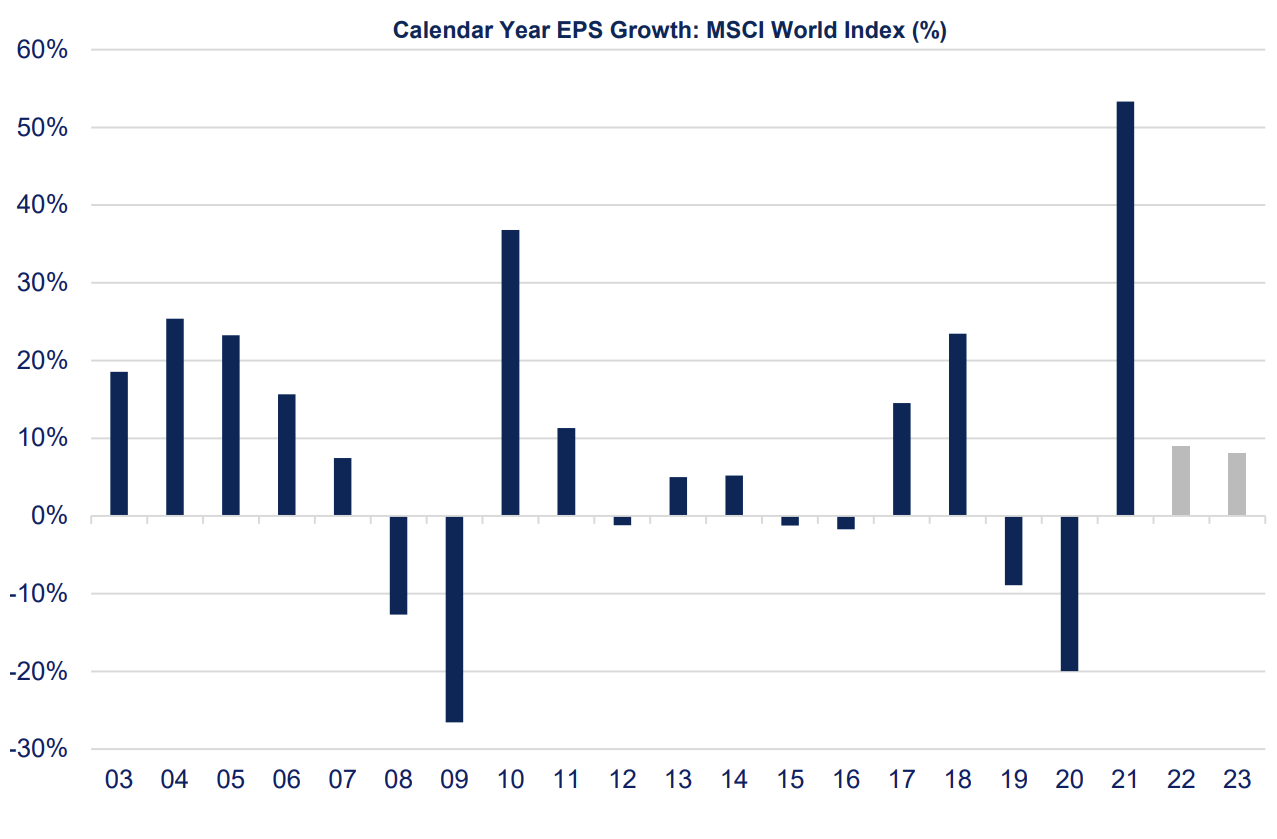

While the vast bulk of the 2022 central bank tightening may have been priced, the likely upcoming earnings contraction has not been. Given the rally since mid-June the key question now for investors is what happens next. The latest US reporting season was more a case of less-bad-than-feared rather than better than expected, but outside energy Q3 US EPS growth was -3% q/qa, and revenue growth (+14% q/qa) being well in excess of earnings growth (9% q/qa) shows that the early cycle benefits of operating leverage have dissipated. Regardless, analysts still remain upbeat about EPS prospects, with expectations for 2022 still above-average at +9% (Chart 6) with 2023 at +8%, which remains above the 40-year average of +5.6%pa.

Chart 6: Consensus estimates for global EPS growth remain optimistic

Source: UBS Australia Limited as at 19/08/22. 2022 and 2023 are consensus estimates.

In contrast to that optimism, our proprietary global EPS model which is based on economic lead indicators suggests that EPS growth for the MSCI World Index will be -4% for 2022, which is well below current consensus forecast, but a flat result after the record high of 2021 (in levels terms and growth which was +53.3%) and in an environment of major cost headwinds, could be viewed as a very good outcome. However, our 8-month forward looking earnings estimate has turned notably negative in early 2023 (-10% y/y in March 2023 - Chart 7). The -10% estimate is beyond the levels typically recorded in economic soft landings (1994/95 and 2017/18) which suggests that there is likely to be significant earnings pressure over the next 12 months, even though a global recession is not yet base case. The two primary drivers of the EPS downturn are the sharp appreciation of the US Dollar and the recent weakness in global consumer sentiment, and if the estimate bears close resemblance to the actual outcome, there should be a fairly significant downgrade cycle ahead.

Chart 7: Global EPS growth is flat for 2022 and turning negative in early 2023.

Source: Bloomberg as at 19/08/22.

Analysts are moving in line with our top-down view

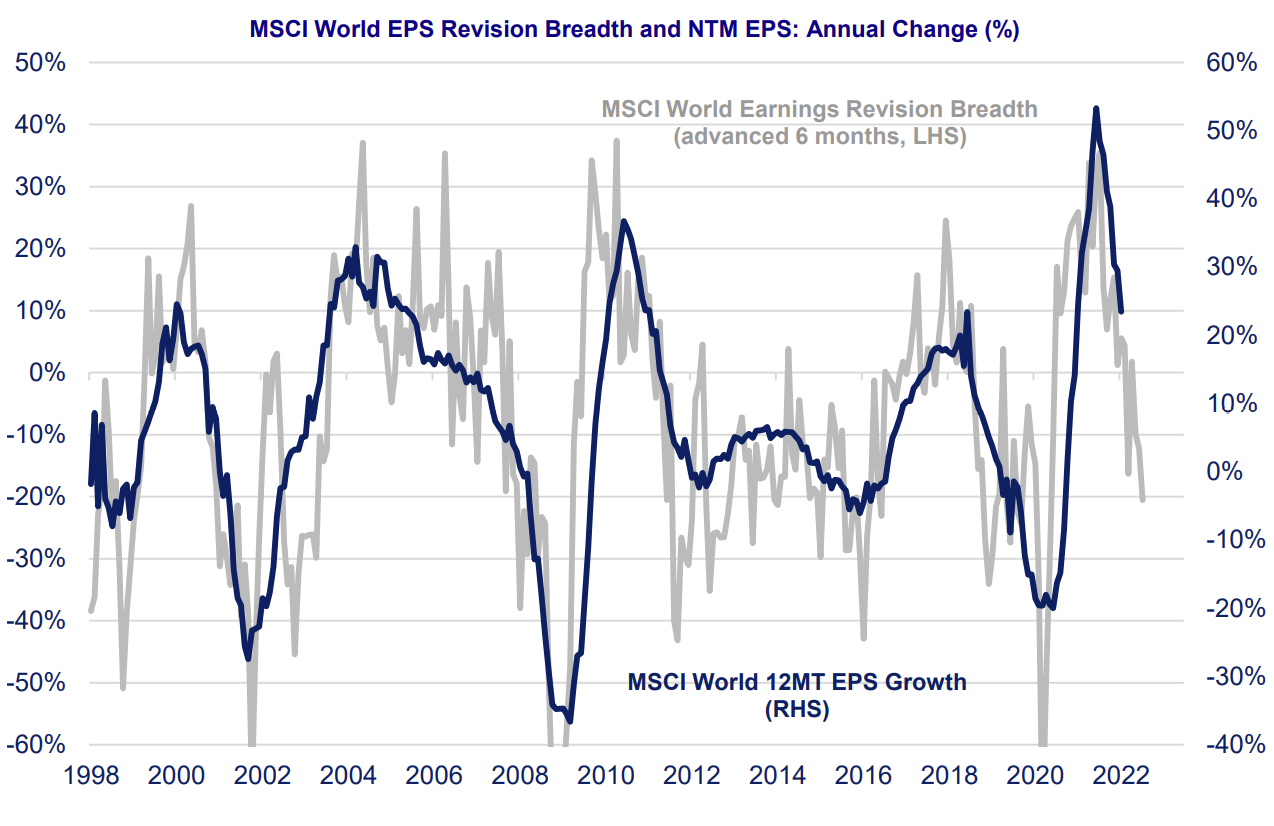

Downside risks to 2022 and 2023 global earnings estimates from our top-down macro model are now being supported by bottom-up estimates from global equity analysts. The global sharemarket’s earnings revision breadth (ERB - which is calculated by the difference between global EPS upgrades and downgrades, divided by total global upgrades and downgrades) suggests sustained elevated scrutiny of earnings estimates is likely going forward. Indeed, on a monthly basis the number of downgrades has exceeded the upgrades for three straight months which last occurred in an economic expansion in 2016 and 2019.

This indicates that forward earnings estimates are likely to be lowered in H2’22 (Chart 8). The decline in regional ERB has been led by the US (-29%), Australia (-25%) and EM (-22%), whereas markets with a more defensive index composition such as the UK (-15%) are not too far behind which makes the upcoming downgrade cycle quite universal. This highlights the importance of a central bank pivot as investors are over looking what seems to be a fairly large downgrade cycle that is currently underway (Chart 8), and this makes the risk/reward trade-off for a sustain leg up in global equities quite unattractive.

Chart 8: Global earnings revisions are moving deeply into negative territory, which makes the Fed pivot key to sustaining market prices

Source: UBS Australia as at 6/08/22.

Concluding comment – a search for new portfolio diversifiers

One of the key themes this decade is likely to be regime change with higher inflation, rising terminal interest rates, increased wages growth, tighter margins, declining profit growth, lower valuations, potentially shorter business cycles and more volatile investment returns. A collection of these factors suggests that the 40-year disinflationary bull market, which produced above average return with below average risk, is over and what lies ahead is a more challenging investment terrain. Many of the markets intricacies within the next 18 months will be governed by the path that inflation takes, and there is elevated uncertainty here, but real cash rates look far too low to have core inflation even within sight of 2% within the next few years, which suggests that central banks don’t have the luxury of pausing and that rates have to continue moving in the ‘restrictive’ direction.

While there is a narrow path for a soft landing, investors need to identify effective portfolio diversifiers to offset the likely rise in equity market volatility, as traditional assets such as government bonds, gold and the Yen have provided little relief so far. Accordingly, investors have to find alternative sources of diversification as already low bond yields are unlikely to provide the level of portfolio protection that it has done in the past, gold is being weighed down by the rising US dollar and the Yen is being handicapped by widening interest rate differentials with the US.

Fortunately, there are numerous other portfolio strategies which can help to diversify equity risk – focusing on companies with strong balance sheets which have high resilience to economic slowdowns and central bank policy tightening, and identifying stocks, sectors, and regions with less valuation risk. In addition, investors need to consider with their financial adviser what is an appropriate exposure to risk markets in the new environment and potentially augment this view with the use of diversifiers. In the Perpetual Diversified Real Return Fund, for instance, we have bought put options on both sharemarket and selected currencies, which can create significant portfolio convexity in periods of market stress. Unlike gold, bonds and the Yen, the key difference with bought put options is that an investor’s downside risk is known, and the benefit is that it gives investors downside protection with upside potential which is an ideal combination for an investment terrain governed by elevated uncertainty.

Learn more

Perpetual’s Multi Asset funds invest across a diverse range of investment opportunities, which can include domestic and global shares, credit and fixed income, cash, property, infrastructure and a range of other investments all combined within a single fund. Visit our website to learn more.

3 topics