Why is the market so high?

Why is the market so high? Why has “value” underperformed? It’s not a simple answer, but it’s not all that complex either. I’ve broken it down to:

- Risk and Return

- Value and Growth

- Interest Rates and Inflation

If you just can’t wait to find out, here’s the summary:

Why is the market so high? It’s not only that interest rates are low for the foreseeable future, but also that over time it has become less risky to invest in equities.

Why has value underperformed? Because “value” as currently defined focuses too near term, and much of the success of growth businesses has been at the expense of “value” stocks.

But if you can bear with me and keep reading to the end, there’s a deeper conclusion to be had.

Return and Risk

The textbook answer is that it’s all about the market’s expectation for return and risk. The return part is easy to understand: sustainably lower interest rates make future earnings more valuable. The hard part to understand is that there have been some trends occurring over decades that have lowered risk too.

I have yet to see anyone consider risk when comparing the high prices of today with the lower prices of yester-year. Investing in stocks was riskier 30 years ago, much riskier 60 years ago, and riskier still 90+ years ago.

How so? Well over that time, the world has become a much safer place in which to buy stocks. Investors are better educated. Companies disclose more information and accounts are more reliable. Security regulators and legislators have closed loopholes and reduced the opportunity for fraud. Calculators and then computers have improved analysis. Technology has allowed everyone from investors, to companies, to regulators to make better-informed decisions, and so be less likely to be surprised. Central banks and governments have become much more risk averse.

Now risk is an important determinant of what a stock is worth. Risk is an input into working out how much you are prepared to pay for future earnings, hence the concept of an “equity risk premium”. The bigger the premium required to compensate for risk, then the bigger the discount rate, and the less you are prepared to pay today. So, part of the answer as to why the market is so high, is that over the years it’s become less risky to invest.

Value and Growth

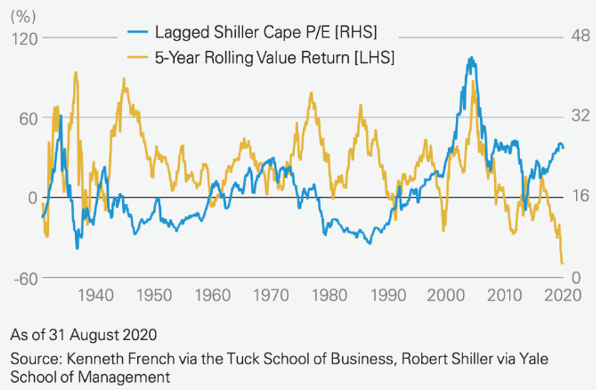

This chart shows that by historic standards, trailing price-to-earnings ratios (“P/Es”) are high, and the return from value stocks has been deteriorating over time.

Of course, stocks don’t keep growing their earnings forever and earnings forecasts are often optimistic. In the past, a lot of the growth achieved by growth companies was cyclical (as shown in the consumer discretionary, media, building materials, or transport sectors). When the economy slowed or went into a recession, companies in these cyclical sectors saw earnings forecasts pulled back much more than those for the less cyclically exposed value stocks (such as in the consumer staples, utilities and property trust sectors).

With a cyclical slow down, the growth stocks would suffer the double whammy of lower forecasts and falling price multiples, and would materially underperform the value stocks.

However, since the tech boom started in the 1990’s, structural growth began to increase in importance versus cyclical growth. It used to be that “tech” stocks were a distinct and small market sector. But new and better ways of doing things have spread rapidly across many industries with the penetration of smart phones, Web 2.0 and cloud computing. Structural growth now is a greater proportion of the market’s overall growth outlook, and it is at the expense of many mature low growth companies.

For example, online retail has decimated many bricks and mortar retailers, regardless of whether they sell staples or discretionary items. Consumers are also shifting away from ownership of assets, like cars or music/movies, to paying as they go. Even the need for travel is reduced with online ordering and video conferencing.

These structural trends are playing out regardless of the economy’s cycle, which means the growth companies’ forecasts are less susceptible to cyclical disappointment, while at the same time they cause of the value companies’ forecasts to weaken. To put it another way, often the success of growth businesses has disrupted and hurt the businesses of value stocks.

But that’s not all. Information and computing technology improvements have also allowed investors to make forecasts further into the future with confidence. I remember the introduction of Lotus-123 and then Excel in the 1980’s which were game changers for analysts. In the late 1990’s, analyst consensus forecasts become widely available, rather than having to contact each broking firm separately to gather and average them, as professional investors used to.

It begs the question which near term earnings multiple should a “value” investor look at to define value. Before computers the proxy used was trailing earnings, or Price to Book, or dividend yield. There were good reasons for that in the past, due to a poor ability to forecast the future earnings with confidence and low availability of data. It is now generally accepted that value is defined by having a low 12 month forward P/E. So we can see that the definition of value moved over time - from the past, to the present, to a little bit in the future.

But in its broadest sense really, value is all about getting earnings for the lowest price and investors look as far out as they can with confidence. It’s not that value investing is failing, it’s that the focus of value is continuing to migrate forward, because it can. Investors are now able to look further into the future to find value.

So why has value done so poorly? First, due to the current definition of value looking at near term earnings multiples rather than longer time periods. Like earlier definitions of value, it has become dated. Second, much of the success of growth businesses has been at the expense of “value” stocks.

Interest Rates and Inflation

Interest rates have supported the stock market and asset prices generally. This has assisted asset price inflation, but not inflation for the price of goods and services. A lower interest rate also reduces interest expenses for companies and consumers.

It would be a big concern for equity markets if interest rates were to rise significantly. Many commentators are concerned that low rates and quantitative easing will “leak” into higher prices, which will require interest rates to rise. Once inflation expectations set in, they can be hard to diminish, as we found out in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Historically, increased money supply did lead to higher inflation; however inflation appears to have become much less sensitive to monetary policy over time. It’s worth getting back to first principals on inflation to explain this.

Prices for goods and services rise when demand pushes against the envelope of supply. Businesses respond to increased consumer demand by putting up prices if they can get away with it. But it’s pretty hard to get away with it when the customers can search for alternative products easily using smart phones, and modern technology has increased the speed at which competitors can identify demand and ramp up production if they see an opportunity to take share. So increased technology and automation has generally kept goods and services inflation low. I don’t foresee a change in this trend in the medium term, so I don’t expect inflation will cause interest rates to rise any time soon.

What does it all mean?

As individuals, we use rules of thumb and jargon to simplify complex relationships. P/E ratios and “value” are classic examples. Over time the usefulness of these simplifications can change to some degree.

The equity market has become a lot more sophisticated, just like pretty much everything else in our world, so it is not surprising that simplifying assumptions need to be revisited.

Benefit at every stage of a cycle

At Monash Investors, we have evolved our investment approach from classic definitions of growth or value to take into account our changing world. Our jargon for describing this is “style agnostic”, and while it is a bottom up fundamental value approach, it incorporates future growth using discounted cash flows. At the same time, we seek to learn from the past by relying on recurring business situations and patterns of behaviour. This means that our approach to investing will continue to evolve.

Hit the contact button to get in touch or visit our website for further information.

1 topic

1 contributor mentioned