Your survival guide to central bank language

What is the first thing you think of when you hear the phrase "central bank"? Philip Lowe? Jerome Powell? Inflation? Interest rates?

When a slew of headlines drop, it can all become too much and too quickly. After all, monetary policy has practically reversed itself in the space of 12 months - from very loose (low rates) to relatively tight (higher rates). All this is in a bid to cool scorching inflation without blowing up the real economy.

The task is, to put it politely, an immense challenge. But every move they make and every word they say is crucial to where your money should be invested.

In the latest of our Investment Guides, I will take you through the quagmire that is central bank speak. From understanding what they do to explaining the challenge ahead, we hope you'll become a better investor by learning how to read the minds of those who set everything from the interest rate to the value of your dollar.

Your reference glossary

Behind the curve: a markets-specific term to suggest central banks were too slow to fight rising inflation.

Forward guidance: a way for central banks to forecast when they expect to hike or cut interest rates materially (that is, either pegged to a particular period of time or to a specific set of criteria)

Money supply: the total amount of money in circulation or in existence in a country

Soft landing: the current mission of most central banks - raise interest rates without engineering a recession.

Targeting: a kind of policy where monetary policy is actively adjusted to achieve a specific rate of inflation

Term Funding Facility: an Australian-specific way of offering low-cost three-year funding to financial institutions. The program, launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, had a huge effect on the number of home loans that could be written because the cost of writing those loans became so much cheaper.

Quantitative easing: setting a target for the value or amount of government bonds that a central bank plans to buy

Yield curve control: one of the most unusual of unconventional monetary policy tools. A program where the central bank commits to buy whatever amount of bonds the market wants to supply at its target price.

In Australia, this was meant to be 0.1% through the pandemic but the markets didn't buy it. In Japan, the program has caused the Yen to be worth the least since 1998 against the US Dollar.

Get more definitions and tips on how to be a more well-rounded investor by taking a look at our glossary page.

So what do they actually do?

Central banks are, without question, vital to the efficient running of a financial system. While every country has some minor differences, their mandates are generally three-fold.

- To keep the national currency stable

- To be a lender of last resort (look up the Lehman Brothers saga, if you're young enough to not remember what that is)

- To keep inflation low and stable, while growing the economy

On that last point, most central banks - including here in Australia - tend to go about this through "targeting". In Australia (and most other major economies), the target range has been 2-3% since the early 1990s.

And how do they do it?

The conventional way is for the central bank to alter the money supply (i.e. how much cash is in the economy). It does that through transactions in the open market - either injecting money in or taking money out through the purchase (or selling) of government bonds.

When there's more money in the economy, there's more for consumers to use and they spend more. Hence, inflation goes up.

Increasing the money supply also decreases the cost of borrowing. Obviously, the opposite would happen if the inverse were to occur.

What did the pandemic change?

In short, the pandemic made a tough job a whole lot tougher. After the end of the GFC in 2008, interest rates around the world were already at nearly zero. This meant that central banks had nowhere to go in this latest crisis. They had to find a way to stimulate a global economy that was shut from going outside and do it without the usual tools.

Most central banks went down one of two routes:

- They bought long-term government bonds (i.e. fixed income securities that don't mature for a long time)

or

- They continued down the conventional route until interest rates fell below zero

While Australia never went down the second route (RBA Governor Philip Lowe explicitly ruled this out in mid-2020), they did take on a lot of other unconventional policy tools. These include:

- forward guidance

- quantitative easing

- term funding facilities

and... perhaps most infamously:

- yield curve control

What is happening now?

Put simply, central banks are trying to catch up to inflation. For a long time, they all said inflationary pressures were going to be limited and fleeting in nature. You may remember the RBA consistently said they did not expect to raise interest rates until "2024, at the earliest". Of course, we now know that's anything but true.

Given inflation has now well exceeded the central bank's target, officials are having to raise interest rates to encourage consumers and businesses to invest instead of spend.

Unfortunately, they are also so far behind the pace of inflation that they are having to hike key interest rates by huge amounts to try and catch up. The idea is that if interest rate hikes are big and done quickly enough, inflation could be tempered without causing a bigger recession.

That's what the professionals and pundits call a "soft landing" - and for more on that, you can read my feature on it:

But even raising interest rates is not a fool-proof strategy - as Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy at Mizuho Bank tells me.

The danger though, given that interest rates are at best a blunt tool, is that taming inflation via interest rates that drives up the cost of borrowing at the price of an economic downturn.

So are they making any progress?

That's the debate markets are having right now. A lot of participants believe that central banks are "behind the curve" - a term explained below by Elliot Clarke, senior economist at the Westpac Institutional Bank.

Essentially it refers to when a central bank takes too long to adjust policy to current and expected economic circumstances, given monetary policy affects the economy with a 6-18 month lag. In this instance, it refers to a market view that global central banks have taken too long to shift their policy stance from ultra-easy to restrictive.

But why is the lag so long? Vishnu explains that changes take time to reflect in consumer wallets.

Higher rates take time to filter through to borrowing costs via banking channels, and eventually to demand. And so a central bank needs to act on not just present inflation (and wider economic conditions) but also on its projection of inflation 6-18 months down the road.

Where do we go from here?

The answer is "more hikes for now". Central banks are knee-deep in this global rate hiking cycle until at least the end of the year. It's 2023 where you will find that the professionals are split.

If you believe a recession is coming in 2023 (Deutsche Bank, TD Securities, Nomura are among the names forecasting a US recession next year), then the following could happen:

- Economic growth will slow (dramatically)

- Unemployment will probably climb

- Stocks, bonds, and house prices may all suffer - to what degree will probably depend on investor sentiment

READ MORE: My esteemed colleague David Thornton has written a piece on how recession calls reflect in equity markets. For more on that, you can click here:

If you don't believe a recession is coming in 2023 (Morgan Stanley, UBS etc), then you can be positioned for such a recovery. JP Morgan's Marko Kolanovic, for instance, does not have recession as his base case. As a result, he remains bullish on risk assets like US equities.

Either way, Vishnu points out that the "perfect storm" has made their task incredibly difficult.

"Containing inflation entails greater risks of jeopardising growth," Vishnu says. "In short, it is a very narrow and precarious path for central banks to manage a "soft landing".

What about in Australia?

Needless to say, most of this commentary is very US-centric. Here in Australia, we have two unique traits that make our economy slightly more resilient to global downturns than in other places. They are - our strong exposure to commodities and our strong labour market.

House prices are where we could see the biggest hit. Australian household assets are particularly sensitive to interest rate changes. If inflation has not peaked yet, then the RBA will have to keep raising interest rates. And if the RBA does that, the house price declines could be even steeper than what we have already seen.

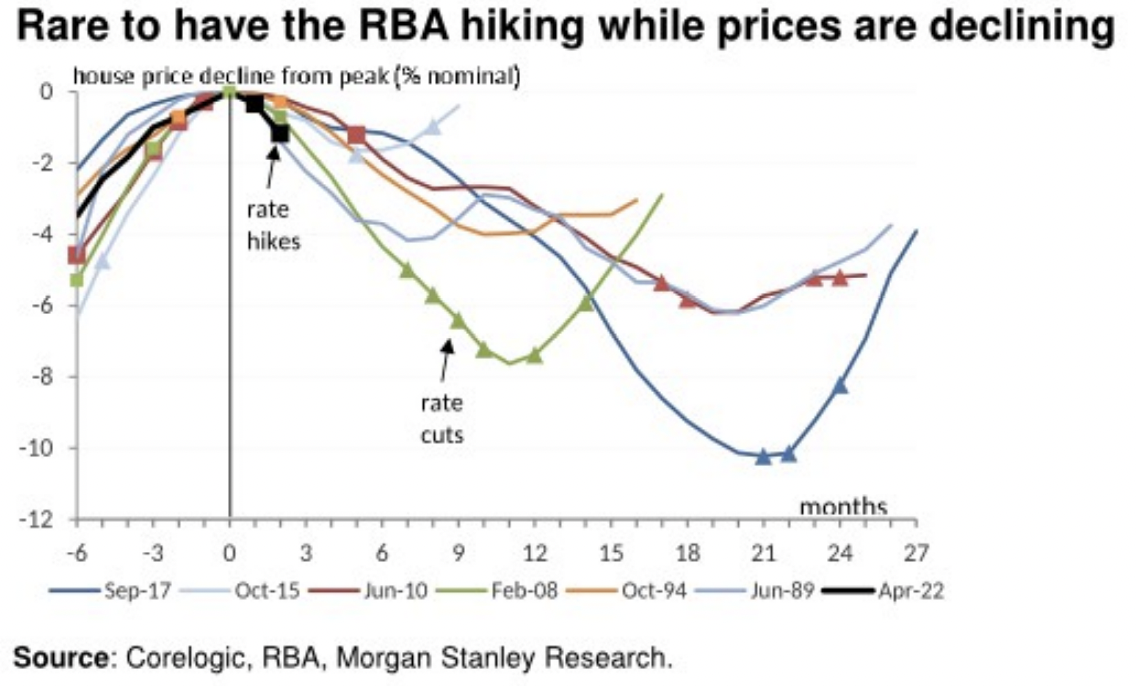

One other thing to note on the subject of house prices. It's relatively rare for the RBA to be hiking rates while house prices are on the decline - as this Morgan Stanley chart shows. They may not say it in so many words, but house prices are a crucial watching brief for the Australian central bank. If house prices fall too far, the RBA has been known to re-consider its plans.

How does this affect my savings account and my mortgage?

I'm glad you asked. The first thing to say is that the RBA's cash rate is not the rate of interest you'll get on your savings or what you'll pay on your mortgage. Why? Clarke says the answer is that both rates are actually quite different.

"Market interest rates for all terms then derive their value from the current and expected path of this 1-day rate [cash rate] plus market conditions and the quality of the borrower," Clarke says.

"The interest rate that a household borrows at is a function of these factors as well as the costs and risks associated with banks providing a loan," Clarke adds.

Secondly, it's different between every financial institution. Finally - and this is the most important point of all - there is a massive difference between a fixed-rate loan (i.e. the rate of interest you pay is locked in for a period of time) and a variable-rate loan (i.e. your rate changes based on the RBA's moves).

If you want any proof of that last point, look at what the Commonwealth Bank did after the July rate hike from the RBA.

Following the second 50 basis point hike in as many meetings, the CBA hiked the rate on a fixed mortgage scheme by 1.4% for maturities between 1-5 years. In fact, if you take out a three-year mortgage, you will pay an additional 5% in interest. While the other banks have not moved this much yet, you can't rule it out.

Never miss an insight

If you're not an existing Livewire subscriber you can sign up to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia's leading investors.

I'll be in charge of asking the questions to Australia's best strategists, economists, and fixed-income fund managers. If you have questions of your own, flick us an email: content@livewiremarkets.com.

4 topics

1 contributor mentioned