Beating APRA's performance test for super funds' fixed-income exposures

Under the hotly contested Your Future, Your Super rules recently introduced by the government, super funds' default products are now subject to an annual performance test based on rolling 8 year returns. If a super fund fails to beat APRA's benchmarks (adjusted for fees and taxes) by 0.5% annually over a rolling 8 year period, it is classified by APRA as an underperforming fund. It must then notify its members in writing using an APRA-prescribed letter that it has failed the test, which will likely trigger outflows. If a super fund fails the test for two years consecutively, it cannot accept new inflows into its default fund.

There is an important debate to be had on the design of APRA's performance test and how it can be further refined to ensure that super funds that have a high probability of hitting their return targets by running lower tracking error to their objectives are not being systematically punished relative to funds that are redlining risk and delivering massive outperformance, albeit with the cost of much larger prospective drawdowns. There is also an important ongoing debate in terms of the choice of correct benchmarks: that is, whether APRA is selecting appropriate indices for each asset-class. I will return to these topics another time.

For present purposes, let's just take APRA's test and its choice of benchmarks at face-value. In the Australian fixed-income asset-class, super funds are benchmarked against the AusBond Composite Bond Index. This is a fixed-rate, rather than floating-rate, benchmark dominated by government bonds. More specifically, it contains bonds with a weighted-average interest rate duration risk of 5.8 years. The average credit rating in the index is very high at AA+. About 92.3% of the index is made-up of Commonwealth government bonds, State government bonds, and bonds issued by sub-sovereign agencies. The remaining 7.7% of the index comprises bank and corporate bonds (aka "credit").

As a result of APRA's performance test adopting this benchmark, super funds will start shifting their Australian fixed-interest exposures to AusBond Composite Bond Index strategies, which will drive demand for the assets in this index. This is likely to see a very significant shift in super funds' asset-allocation away from short-duration fixed-income into longer-duration portfolios that run interest rate risk that is comparable to the Composite Bond Index's duration exposure, which is the single-biggest driver of the benchmark's return. Whether this is a good or bad thing is an open question.

Since about 26% of the Composite Bond Index is comprised of State government bonds (aka "semis"), and these assets pay substantially higher yields than Commonwealth government bonds, it is likely that many super funds will go overweight this sector as a simple way to drive excess returns above and beyond the benchmark without introducing material illiquidity or tracking error risks.

The problem with just loading up on credit is the illiquidity risk, which was exemplified in March 2020 when many Aussie credit funds de facto froze. The risk of liquidity shocks has been amplified with the precedent of the Commonwealth government allowing super fund members to release their savings early, as occurred in 2020, forcing many super funds to liquidate assets. (Some discovered that they were carrying too much illiquidity in the form of unlisted assets that were difficult, if not impossible, to dispose of.)

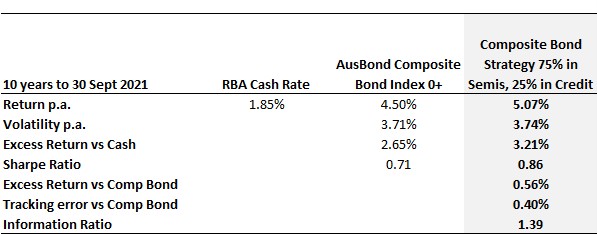

This begs the question: how can super funds confidently beat the Composite Bond Index? As an illustration of one simple excess return driver, we have adjusted the portfolio weights in a hypothetical Composite Bond Strategy with a tilt away from Commonwealth government bonds towards State government bonds and credit. In particular, we have assumed this Composite Bond Strategy is roughly 75% invested in semis (vs the index weight of 26%) with the remaining 25% allocated to credit. The table below shows the results of this experiment over the last 10 years, which helpfully includes the March 2020 pandemic shock.

What we find is that a portfolio 75% weighted to State government bonds (proxied by the relevant duration-matched AusBond indices) and 25% in credit (proxied by the duration-matched AusBond Credit Indices) beats the Composite Bond Index by 0.56% annually over the last 10 years with almost identical volatility of 3.74% pa (vs the index volatility of 3.71% pa). It therefore has a superior Sharpe Ratio of 0.86 times (vs the index's Sharpe of 0.71 times). It also has a low tracking error to the index of just 0.40% pa with a high Information Ratio of 1.39 times.

Here it's worth noting the highly experienced Warren Bird's comments regarding the effective risk arbitrage between Commonwealth and State government bonds. Bird comments in a recent post:

I think we had a discussion once before about semis being a "gimme". While that particular way of putting it may be a bit strong, your analysis aligns with my long-held view (going back 25 years, not just 10) that a core overweight to semis shifts you to a more efficient frontier- higher return with less risk. Put a few corporates in to bump the risk back up to index and the return is even better. I wrote about that in my old KangaNews column in 2013. Good to see it's held up over the years since!

It is well known that most active Composite Bond Index strategies tend to underperform the index. This is almost certainly a function of their active interest rate duration bets. The interest rate derivatives market is immensely efficient in pricing the probabilities of future interest rate changes. Despite many folks thinking they can outwit this market, it is, in practice, hard to find consistently exploitable mispricings in rates and FX. And this is why it is hard to find active managers that consistently beat the Composite Bond Index.

It would not be surprising see active managers shift away from using rates strategies that introduce high probabilities of underperforming the index, and high tracking error. A safer and simpler approach would be to tilt the portfolio weights to higher-yielding assets without introducing unacceptable illiquidity and/or volatility risk.

Access Coolabah's intellectual edge

With the biggest team in investment-grade Australian fixed-income and over $8 billion in FUM, Coolabah Capital Investments publishes unique insights and research on markets and macroeconomics from around the world overlaid leveraging its 16 analysts and 5 portfolio managers. Click the ‘CONTACT’ button below to get in touch.

4 topics