Is EPS the best factor for measuring investment success?

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the importance of Return on Equity (ROE) as a financial metric.

Today, let’s turn to Earnings Per Share (EPS).

EPS is ubiquitous.

Investors see it almost instantly when first searching a stock. The financial press promulgates EPS figures widely. Then, there’s the EPS consensus estimates — the ones that determine whether a company beats expectations or not.

Let’s also not forget the role EPS plays in coming up with price targets. As a company’s EPS grows, the thinking goes that so too will its share price on the assumption that its P/E ratio will remain constant or even expand.

Clearly, EPS is a hugely popular metric.

But is it useful? In this wire, I'll make the case for why it isn't.

Earnings per share don’t matter

Nearly five decades ago, economist Joel Stern — developer of the economic value added concept — published a trenchant piece in the Financial Analysts Journal.

The title didn’t pull punches, ‘Earnings per Share Don’t Count’.

Stern claimed the fact that ‘EPS is easy to calculate is an insufficient excuse for employing it as an analytical device’. In short, easy isn’t necessarily best.

So why doesn’t EPS matter? Because sophisticated investors look elsewhere when assessing a stock’s overall performance.

Stern offered a thought experiment.

Consider two companies, X and Y.

Both are the same in every way, with earnings expected to rise at the same rate of 15%.

At this stage, Stern muses, it would be ‘foolish’ to ask which company should sell at a higher price. Clearly, X and Y should trade at the same valuation!

But then Stern adds a wrinkle (emphasis added):

"However, with the addition of one other piece of information about the two companies, we must conclude that X would command the greater market price. Assume we learn that X requires almost no investment in new capital to increase its profits 15 per cent annually, whereas Y requires a dollar of additional capital for each incremental dollar of sales.

X should sell at the higher price and PE because it requires less capital than Y to grow at a given rate despite the fact that X and Y are expected to have identical future profits," Stern wrote.

"This is because X has a larger expected rate of return on incremental capital. The key determinant of market price in this case is the expected rate of return on incremental capital invested. The implication of this example is that investors do not simply discount expected earnings; rather they discount anticipated earnings net of the amount of capital required to be invested in order to maintain an expected rate of growth in profits.

We shall refer to the latter stream as the expected future “Free Cash Flow,” the expected future stream of cash flows that remains after deducting the anticipated future capital requirements of the business," he added.

Stern concluded it’s free cash flow that moves markets, and that EPS is ‘immaterial’.

Valuation experts Michael Mauboussin and Alfred Rappaport made similar points in their latest edition of Expectations Investing.

The duo argue that a stock can grow EPS without creating shareholder value.

How is that possible? The pair write:

"This broad dissemination and frequent market reactions to earnings announcements might lead some to believe that reported earnings strongly influence, if not totally determine, stock prices."

"The profound difference between earnings and long-term cash flows, however, not only underscore why earnings are such a poor proxy for expectations, but also show why upward earnings revisions do not necessarily increase stock prices."

The shortcomings of earnings include the following:

- Earnings exclude a charge for the cost of capital

- Earnings exclude the incremental investments in working capital and fixed capital needed to support a company’s growth

- Companies can compute earnings using alternative, equally acceptable accounting methods’

EPS and professional incentives of equity analysts

If you’re an equity analyst, it serves your interest to focus on EPS estimates. You have four chances every year to prove your analytical chops. And if your quarterly EPS estimates are accurate enough often enough, your future forecasts get compiled to create the consensus forecasts everyone sees.

It makes sense for equity analysts to focus on EPS so heavily. But that shouldn’t mean investors must too.

In any case, the professional reliance on EPS should be disregarded.

Respected investor Martin Fridson reiterated this point in his latest book:

"The equity research establishment’s over-reliance on EPS might be more excusable if earnings invariably represented a genuine creation of economic value on behalf of shareholders. In practice, the gap between reported earnings and bona fide profits can be vast."

"Sometimes the mismatch reflects outright accounting fraud. But investors shouldn’t be lulled into believing that they’re getting the straight dope on a company’s earnings merely because none of its executives are under indictment."

"Reported EPS can diverge from the underlying reality because of perfectly lawful accounting practices or because the numbers dispenses in quarterly financial statements are later said to have been mistakes."

And in the long run, sophisticated investors do seem to disregard earnings, corroborating Stern’s earlier point.

Empirical research shows that earnings surprises, for instance, explain less than 2% of share price volatility in the four weeks surrounding the surprise announcement.

In other words, investors "place far more importance on a company’s economic fundamentals than on reported earnings," according to McKinsey’s Tim Koller and Marc Goedhart.

EPS forecasts: should investors bother?

Plenty of studies have shown the inaccuracy of earnings forecasts. In particular, research shows analysts’ estimates are heavily biased toward ‘excessive optimism’.

Another study found that 40% of the time, an EPS forecast generated from a time series of past data (the quarterly earnings for a company over the past five years, for instance) was as or more accurate than the analysts’ consensus estimate!

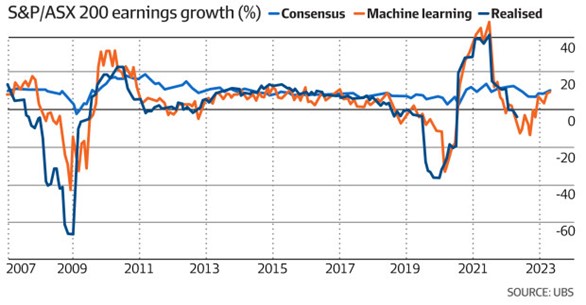

So, I wasn’t surprised when last Sunday I read about a quant team in UBS spruiking the forecast outperformance of its machine learning model.

Here’s the story in the AFR:

"Five years on, and equipped with more data and more powerful computers, investment bank UBS’ quantitative research team reckon they’ve finally cracked it. They’ve built a model that shows the machines can finally out-forecast the humans, including in Australia. The model comes up with 12-month forecasts and the best bit, according to the quant analysts, is that it is completely unbiased. Its numbers are typically lower than consensus."

"The regression model is always trying to pick a company’s earnings over the coming 12 months. It uses prior year earnings as an anchor starting point (about 75 per cent of the end value), and uses a range of traditional quantitative signals and metrics (cash flow growth, for example) and macro factors. It’s all written in Python computer code.

"The model is smart enough to work out how the company’s earnings have responded to macro factors like bond yields, currency and oil pricing, consider current levels and use that to formulate the earnings forecast. It works on a company level but can also be aggregated up to a sector or market level..."

Source: Australian Financial Review

Yet, if earnings as measures by EPS don’t really matter, neither do accurate forecasts — whether human or AI-generated.

In investing, picking your battles matters just as much as how well you wage them. Battling others to more accurate EPS estimates may be a battle not worth starting.

Click this link to subscribe to Money Morning.

5 topics

.png)

.png)