The yield curve, recessions and soft landings

One of the accepted truisms in modern finance is that a lot of information can be derived from the yield curve.

The US yield curve

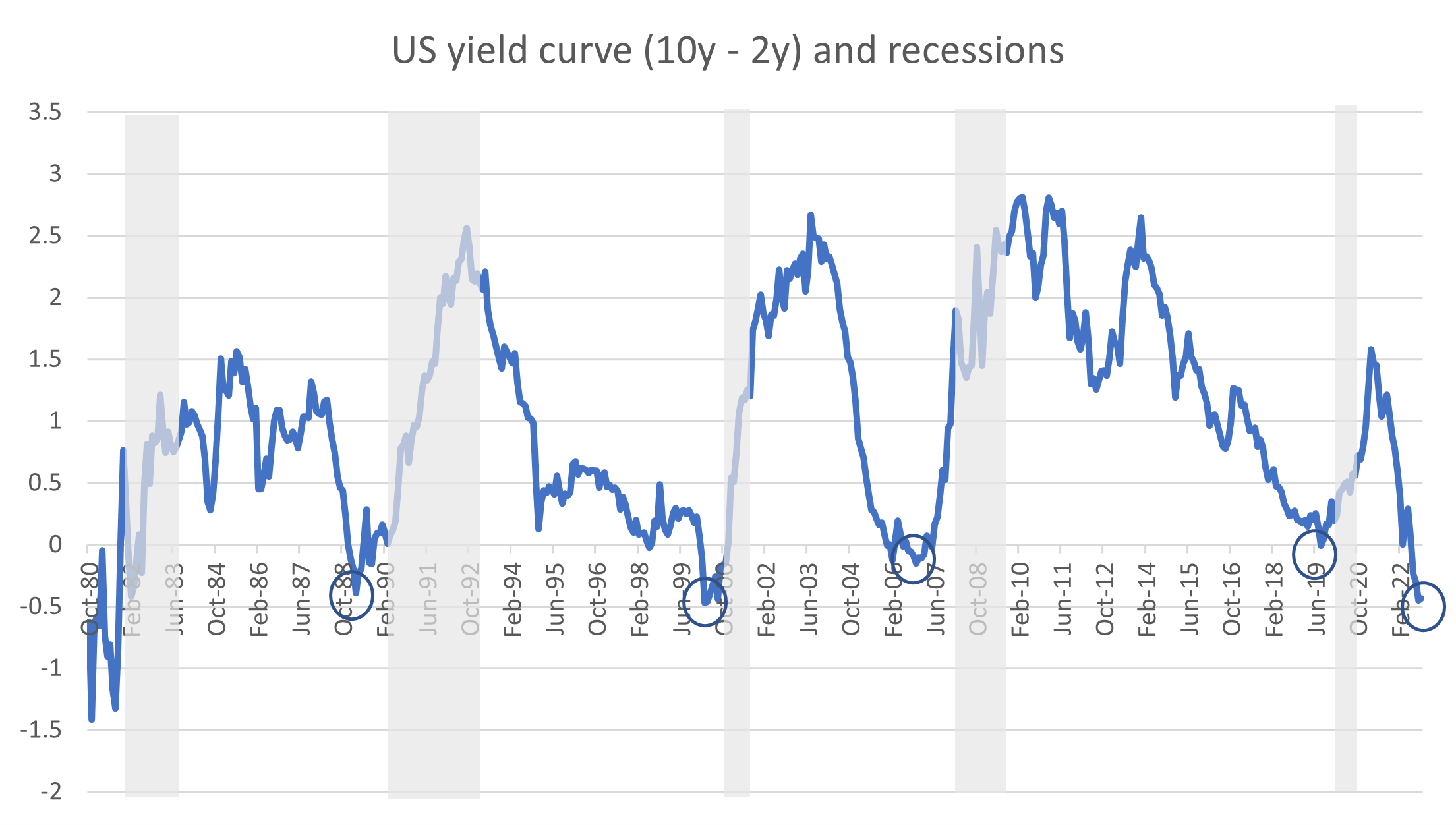

A positive sloping curve (as measured by the 10-year bond yield being higher than the 2-year yield) suggests solid expected economic growth. A negative sloping curve (long-term rates lower than short-term rates) suggests a slowdown and economic recession.

When we look at the data, each time the yield curve turns negative in the US, a recession (grey shaded area below) soon follows – which is quite a worry, the yield curve is currently negative.

Theoretical rationale of the inverted yield curve

As we highlighted in last month’s Investment Perspectives article, No, bond vigilantes don’t exist for monetary sovereign, long-term interest rates (such as the 10-year bond yield) are nothing more than the return one would expect from holding cash over the same timeframe. That is, bond yields reflect the expectation of the future cash rate.

When bond yields are lower than the cash rate, bond investors are pricing in future interest rate cuts, which only seem to occur when an economy is in recession. Hence, theoretically, an inverted yield curve is a prediction of a recession in the near term. And looking at the track record in the chart above, bond investors have a pretty good strike rate.

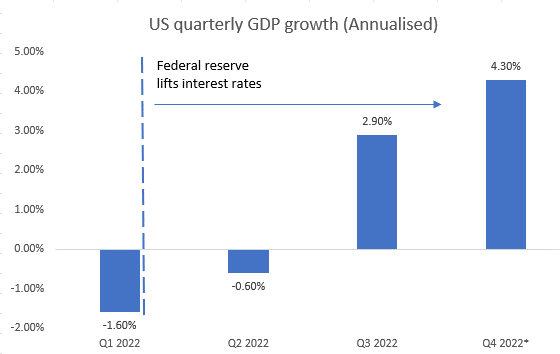

But there is currently no sign of a US recession

We returned from the NAREIT conference last month after visiting a number of companies. While the overriding themes were capital markets and cost of funding (interest rates), each company is sensibly on ‘recession watch’, yet see no wavering consumer or tenant demand. This is consistent with wider macroeconomic data that shows economic growth has actually (uncomfortably) accelerated since the US Federal Reserve began to increase interest rates in March 2022.

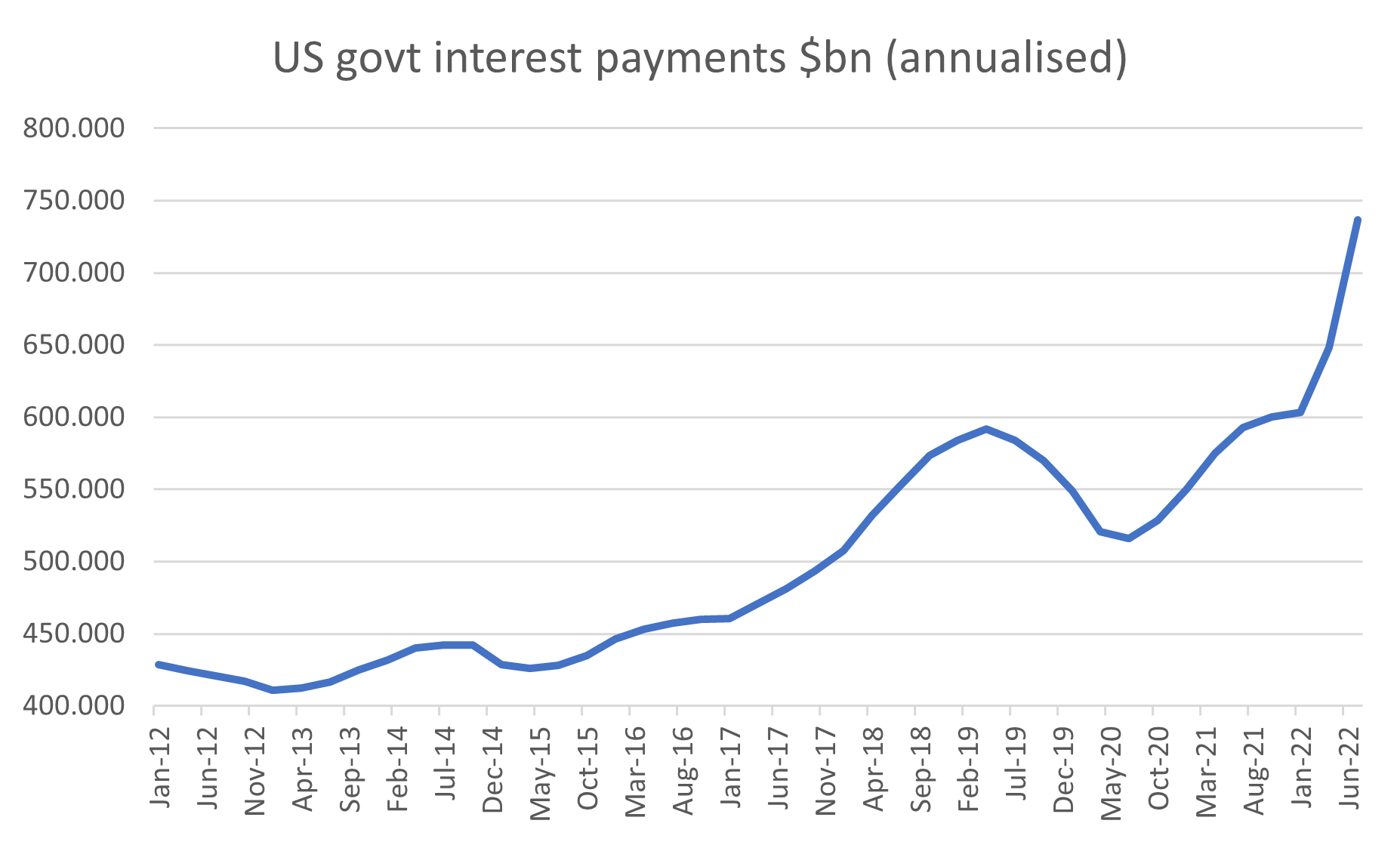

Regular readers of our articles shouldn’t find the data above too surprising. As we highlighted in our recent article, Why rising rates aren’t working yet, higher interest rates are increasing government fiscal spending via the interest-income channel, adding to overall demand supporting employment and spending. The current run-rate of interest payments ($750bn and growing) is almost the size of the US defence budget.

The yield curve may not be predicting a recession

So, GDP growth is accelerating, yet the bond market is predicting an imminent recession.

Despite the seemingly excellent track record of the inverted yield curve predicting recessions, we note the US Federal Reserve began to pre-emptively cut interest rates in August 2019 – without any sign of an initial recession. Ultimately, there was a very short pandemic-induced recession in early 2020, however it would be a stretch to suggest bond investors predicted the pandemic. So, the yield curve’s track record is certainly not perfect.

In other words, an inverted yield curve correctly forecasts lower official interest rates, but that may not mean a recession.

The fact is, from a macro perspective, we have no recent playbook that considers:

- a global pandemic

- massive co-ordinated fiscal stimulus

- un-even re-opening of world economies, while

- supply chains remain globally linked.

If we were to search for any recent economic parallels, we feel the closest to today is the late 1940’s, just after the Second World War, where:

- there was a demand shock (from returning soldiers)

- there were domestic supply constraints as the US re-configured from a war economy to a domestic consumption economy

- there was near-zero assistance in global supply from a war-ravaged Europe and Asia.

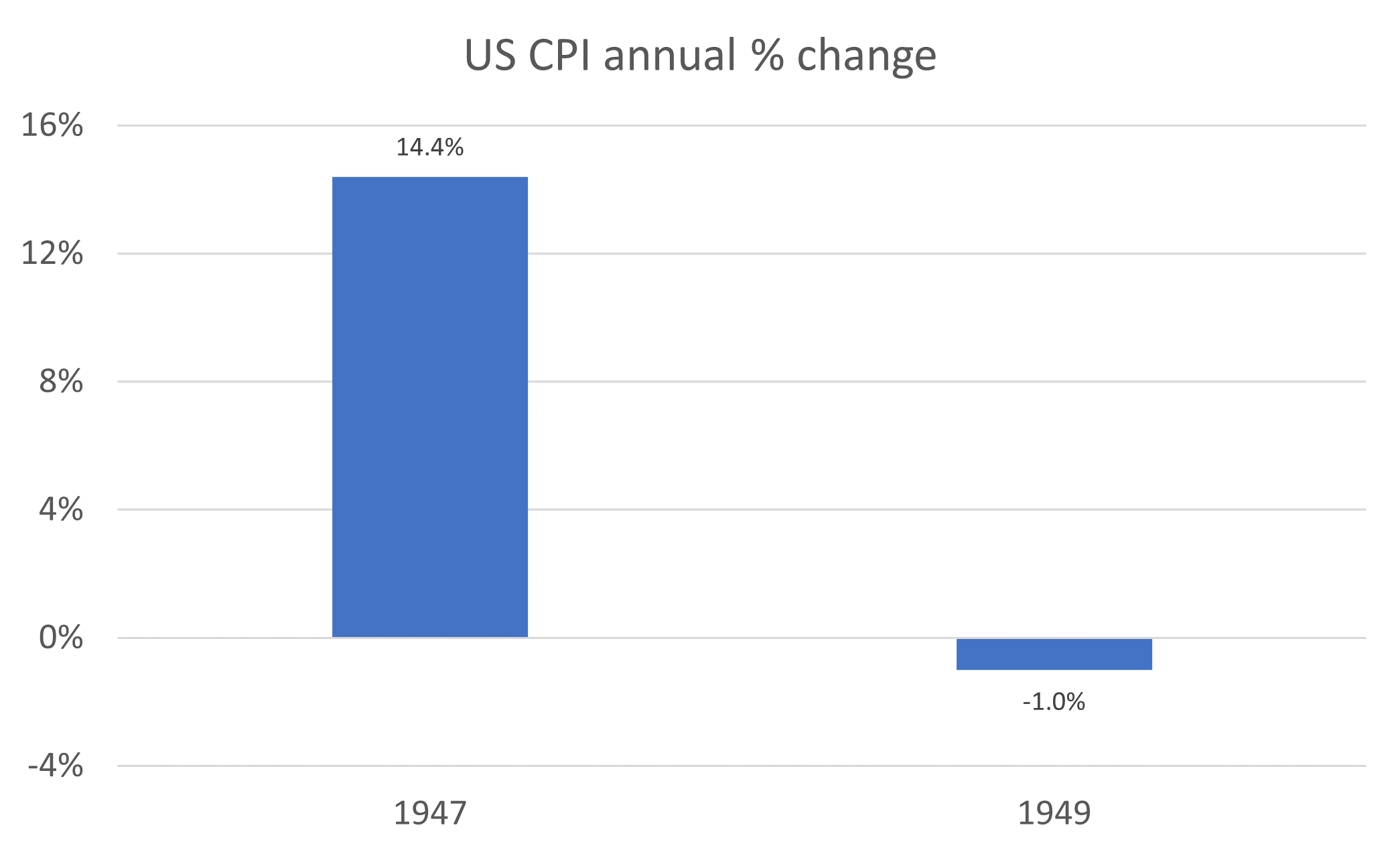

The coordinated demand shock and supply constraints of the 1940’s saw inflation surge to 14.4% in 1947, only for deflation to take hold two years later, as supply caught up with demand.

If the current environment mirrors the late 1940’s, we could be facing deflation within the next 12-24 months, which may pre-empt the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates in a still growing economy.

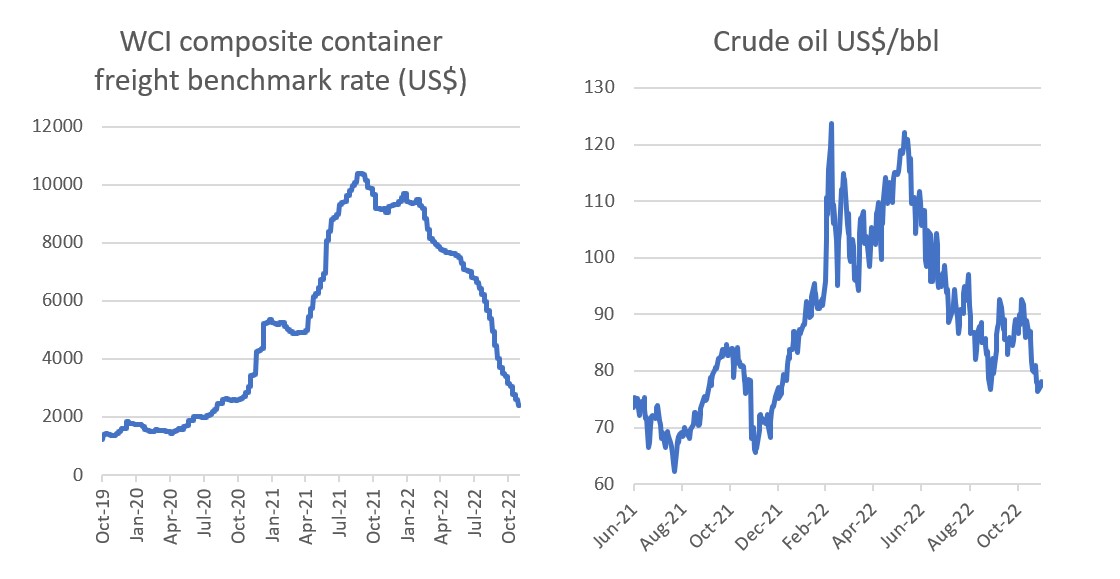

The odds that this is the case appear to be increasing. Despite accelerating Q4 GDP growth, key macroeconomic indicators which drove inflation in the first half of the year (such as freight rates and oil) have reversed, and residential rental growth is showing signs of meaningful deceleration.

For investors sitting in cash awaiting a recession (as informed by the yield curve), there is a chance the curve is correctly anticipating falling interest rates without a recession and yet still growing corporate profits. Under such a scenario (i.e., a soft landing), such an allocation may be a mistake.

Concluding thoughts

It is indeed a confusing macroeconomic backdrop. Since March, the US Federal Reserve has embarked on the fastest increase in official interest rates in a generation. It therefore seems reasonable to expect some type of economic slowdown or recession. Yet, since the US Federal Reserve began the rate-hike cycle, GDP growth has accelerated, the employment market remains solid and consumer spending robust.

As we suggested back in 2021;

“This is not a normal cycle – not many readers of this article (including ourselves) are fully equipped to understand the macroeconomic ramifications of such an incredible sea change in policy and household financial health. The only comparable period was probably the net fiscal transfers from WW2, which set up the US middle class to boom for the following 20-30 years.”

If the current environment is more like the 1940’s than the 1970’s, the yield curve may be right – but a recession may not occur, profits may continue to grow, and those sitting on cash may miss the opportunity.

It’s always hard to bet against history, and the US yield curve has a formidable track record predicting recessions. But this one time, it may be telling us something else.

Investing in global listed real estate

Quay Global Investors, a Bennelong Funds Management boutique, focuses on the preservation and creation of wealth through innovative strategies in real estate securities. For more insights on global property, visit Quay’s website.

4 topics

2 funds mentioned