Why the NSW Budget could be $9.5bn better off after Commonwealth flood support

The NSW budget remarkably remained close to balance in February, as yesterday's data release shows, providing welcome news for NSW Treasurer Matt Kean. The budget deficit is likely to come in $5 billion better than the full-year government forecast for 2021-22 (i.e., FY22), even allowing for conservative estimates of the potential costs of recent tragic flooding and assuming that the Commonwealth's reimbursement of 75% of the cost of this natural disaster does not arrive until next financial year.

If the Commonwealth reimbursed NSW for its 75% share of the floods this financial year, via an advance, the budget could be as much as $8.5-$9.5bn better off. While it is more likely that the Commonwealth payments are made in the next financial year or later, there is a possibility that an advance is made due to the pending federal election in May.

These upside budget surprises should reduce NSW's debt funding task by a similar quantum in 2022-23 (or FY23). Further outperformance over the remainder of 2021-22 (or FY22) could potentially reduce NSW's debt funding needs by more than $5bn in the next financial year before accounting for the very substantial impact of infrastructure delays, which we previously analysed here.

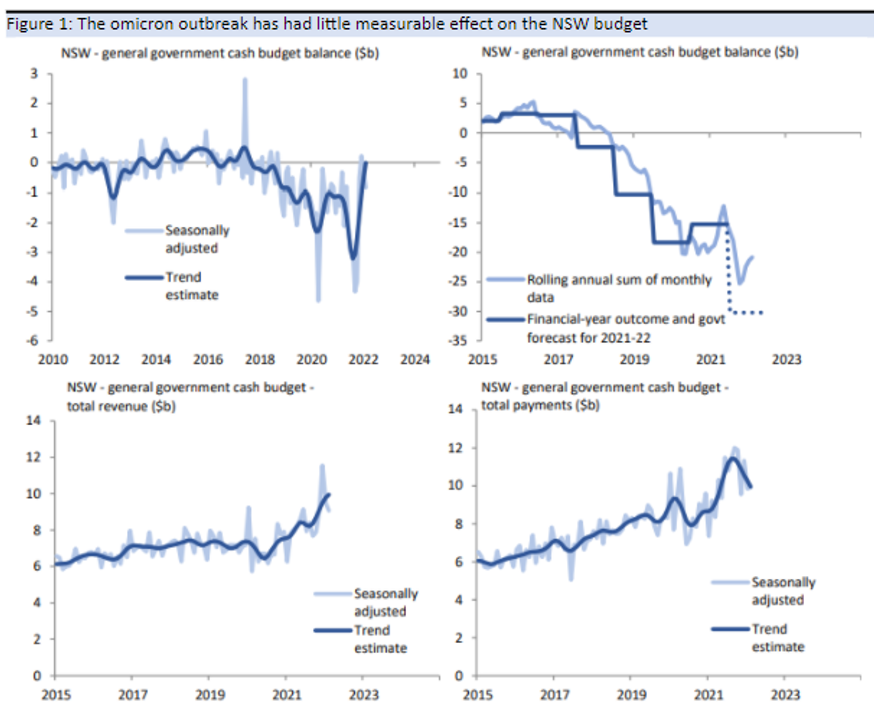

The NSW budget has been very volatile over recent months even after seasonal adjustment, but the omicron outbreak has not had a measurable effect on the bottom line, contrasting with the large deficits posted during the delta outbreak. This contrast reflects more targeted assistance to the community during omicron and a more limited impact of the outbreak on the economy.

The general NSW government budget on a cash basis was broadly in balance in trend terms in February (i.e., close to surplus), although this will very likely be revised to a modest deficit as more data become available given how trend estimates are calculated.

This is clear from the seasonally adjusted estimates, which showed the deficit widened from about $500 million in January, when the budget was similarly close to surplus, to almost $1 billion in February, while flood-related costs will add to the deficit over the coming months (subject to the timing of the Commonwealth's reimbursement of 75% of these costs).

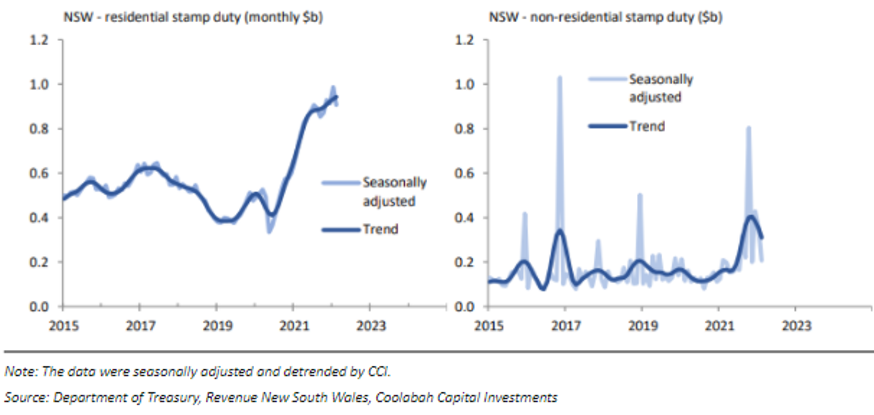

The improvement in the NSW budget over the financial year to date mainly reflects stronger revenue, particularly grants and subsidies, but payments have fallen and are back at pre-delta levels, with a large fall in financial assistance payments to households/businesses.

The budget is likely to come in about $5bn better than government expectations for this financial year, even allowing for the economic and fiscal cost of the tragic floods in northern NSW and ignoring the fact that the Commonwealth will pay for 75% of the cost of the floods.

The government has forecast a deficit of $30bn for 2021-22 (FY22) as a whole, but the rolling annual sum of the monthly numbers shows the deficit over the past twelve months has narrowed from $25bn in October/November to $21bn in January/February.

Conservatively allowing for about $5-6bn in New South Wales government assistance and economic fall-out from the floods – where payments could well end up being spread into 2022-23 – the deficit for this financial year is on track to come in about $5bn better than the government’s full-year estimate of $30bn. This is an improvement on Coolabah's previous estimate using NSW's monthly budget data for January, where we assumed $5bn in flood costs, which implied the deficit could come in $4-5bn better than expectations.

The Commonwealth will reimburse 75% of NSW's direct disaster costs, which means that the NSW budget will improve further when those payments are made in arrears, where the Commonwealth has said that these costs are currently unquantifiable. Net of the Commonwealth's reimbursements for flood expenses, the NSW budget could be about $8.5-9.5bn better off, although this is more likely to be realised next financial year after the state has applied for a reimbursement.

The pending federal election in May raises a possibility that the Commonwealth makes an advance on these payments, as it did in 2010-11 with the floods and cyclone in Queensland.

For next financial year, NSW should benefit from a materially reduced debt funding task in the order of $8.5-$9.5bn if reimbursement is made that year. If TCorp issues debt in line with its official funding task for FY22, which was last updated in December, it would be effectively pre-funding something like this amount for FY23.

Given the state of the economy, it is reasonable to assume that all states and territories are also experiencing some degree of outperformance of their official deficit forecasts, which paves the way for lower debt issuance in FY23 given the states will have done a lot of pre-funding by sticking to their official debt issuance tasks. Victoria is a stand-out because it is running more than $5bn ahead of its official debt issuance task in FY22, which means that it might have unwittingly done significant pre-funding for FY23, much as it had done in FY21 (this FY21 pre-funding ended up having to be used for to pay for the cost of the COVID lockdowns).

Separate to the tracking of budget performance, in recent research we have quantified the impact of delays to infrastructure spending on state issuance, which the empirical data suggests will lag government forecasts by 10% to 20%. Given the currently very tight labour market and supply-chain blockages, where New South Wales is reportedly considering delaying a number of "mega-projects", we estimate this could reduce the states' debt funding needs in FY23 by another $8bn (assuming 10% delays) to $16bn (assuming 20% delays).

3 topics